Soon after meeeting Susan B. Anthony in 1895 at a convention of the National-American Woman Suffrage Association (N-AWSA) in Atlanta, Adella Hunt Logan wrote to the suffragist leader, “I am working with women who are slow to believe that they will get help from the ballot, but someday I hope to see my daughter vote right here in the South.” She strove to spur often frightened or otherwise reluctant black women to political action through gaining access to the ballot; she lobbied for equal pay as well, and ultimately espoused women’s reproductive rights.

The letter and Hunt Logan herself were virtually unique, because in her own eyes, and as specified by law, she was “a Negro.” Due to her predominantly Caucasian ancestry, however (both her mother and her black-Cherokee-white maternal grandmother maintained longstanding, consensual relationships with slaveholding white men), Hunt Logan herself looked white. As an adult, she occasionally “passed” to travel on the Jim Crow South’s railways, and to attend segregated political gatherings, such as the N-AWSA’s, from which she brought suffrage tactics and materials back to share with her own people. At the time, she was the N-AWSA’s only African-American lifetime member, and the only such member from ultraconservative Alabama, where she lived with her husband, Warren Logan, and their children, and taught for three decades at Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, the agricultural and industrial school for black Southerners that drew such prominent visitors as Frederick Douglass, Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, and philanthropists Andrew Carnegie and Julius Rosenwald.

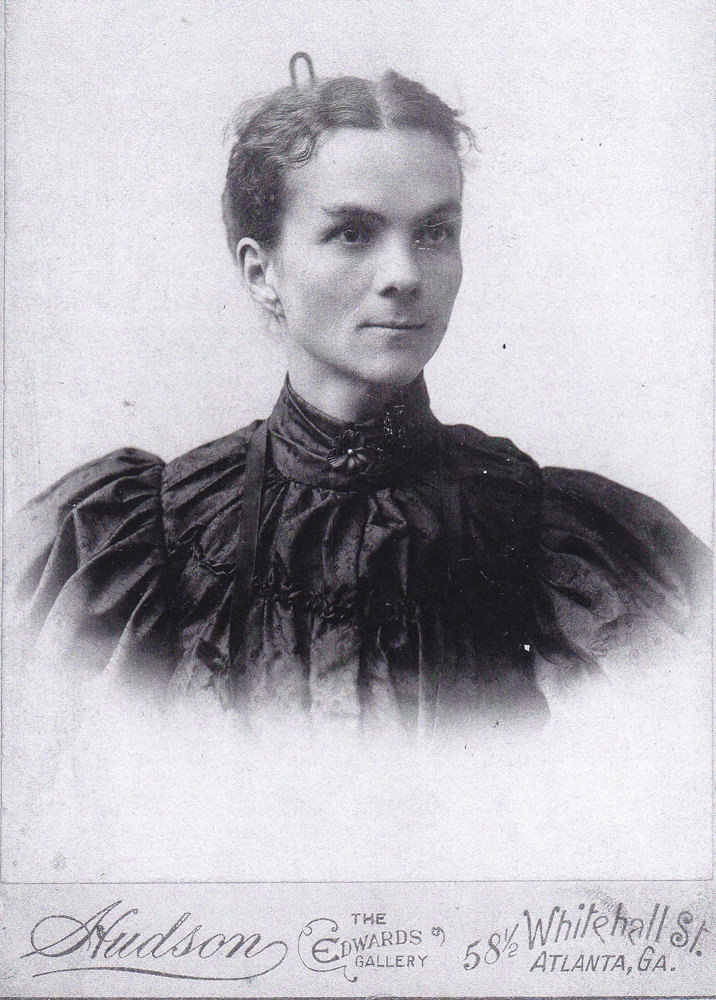

Hunt Logan in June 1901, after earning her “honorary” master’s degree from Atlanta University

Collection of the author; reproduction photograph by Mark Gulezian

Hunt Logan was also a woman of rare privilege and education. She’d first been tutored by a white cousin, a schoolteacher. She graduated at 18 from Atlanta University, where dedicated New Englanders taught a small cadre of black Southerners, and 20 years later she earned a master’s there—“honorary” only, though, because no school for African Americans anywhere in the country then was accredited to bestow “earned” graduate degrees.

Her interactions with Anthony continued, despite a fractious incident in 1900. A white friend and fellow suffragist suggested that Hunt Logan speak at a Washington, D.C., convention honoring Anthony’s eightieth birthday, noting, “her hair is as straight as yours or mine and she looks white but must call herself colored.” But Anthony demurred: “I cannot have speak for us a woman who has even a ten-thousandth portion of African blood who would be an inferior orator in matter or manner, because it would so mitigate against our cause…Let your Miss Logan wait till she is more cultivated, better educated, and better prepared and can do our mission and her own race the greatest credit.”

Despite that affront, Hunt Logan cajoled white suffragists, Anthony among them, into visiting Tuskegee, and contributed to the N-AWSA’s Woman’s Journal, where in 1901 (using the pseudonym “L.H.A.”) she wrote about “Mrs. Warren Logan’s” recent public presentation on suffrage for black women. She wrote for other publications as well, including a notable 1905 article about woman suffrage in the Colored American, the country’s most widely read journal by, for, and about African Americans. “If we are citizens,” she asked, “why not treat us as such on questions of law and governance where women are now classed with minors and idiots?” To those who argued that men represented their wives at the polls, she argued that many of her sex either had no spouses or had “callous husbands who patronize gambling dens and brothels.” Such women, she concluded, often stayed home, “to cry, to swear, or to suicide.”

In 1912, in “Colored Women as Voters,” written for W.E.B. Du Bois’s popular new NAACP magazine, The Crisis, she argued in part, “More and more colored women are participating in civic activities, and women who believe that they need the vote, also see that the vote needs them.” But by then, she was already physically ill—from long-term, painful, and debilitating kidney infections—and increasingly depressed, a condition due partly to marital and family stress, but aggravated by outside events. Du Bois, though Hunt Logan’s friend, was Booker T. Washington’s philosophical archenemy, and he failed to request a contribution from her for his second issue of The Crisis to be devoted to woman suffrage. Early in 1915, the Alabama legislature had refused to allow a referendum on votes for women even to appear on that fall’s ballot. Enforced electroshock treatment at Michigan’s Battle Creek Sanitarium, after she’d set a small fire in her husband’s office, was cut short that November following Washington’s death.

She returned to find a campus deep in mourning, and to face rumors of her husband’s infidelity. Just before Washington’s December memorial service, she jumped to her death from the fifth floor of a campus building before hundreds of appalled onlookers—as perhaps she’d prophesied in her 1905 suffrage article.

Despite her struggles, Hunt Logan boldly challenged the status quo and conventional wisdom about politically empowering African-American women. Ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 officially granted women the right to vote, but Southern black women, her main constituency, largely had to wait until passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act to exercise the franchise.