How to ensure that everyone can live a life with opportunity and meaning is an enduring question. It is also a question related in part to where people live. Are homes and neighborhoods vibrant, safe, affordable, and nurturing? Do they support different kinds of people living different kinds of dreams? What are the roles of the private sector, individuals, and experts in building these good communities? What roles do governments have in making places healthy, supporting local initiatives and preferences, and creating a framework so that everyone contributes toward the common good? At a time when such questions are barely being asked, at least at a national level, an historical perspective is especially valuable.

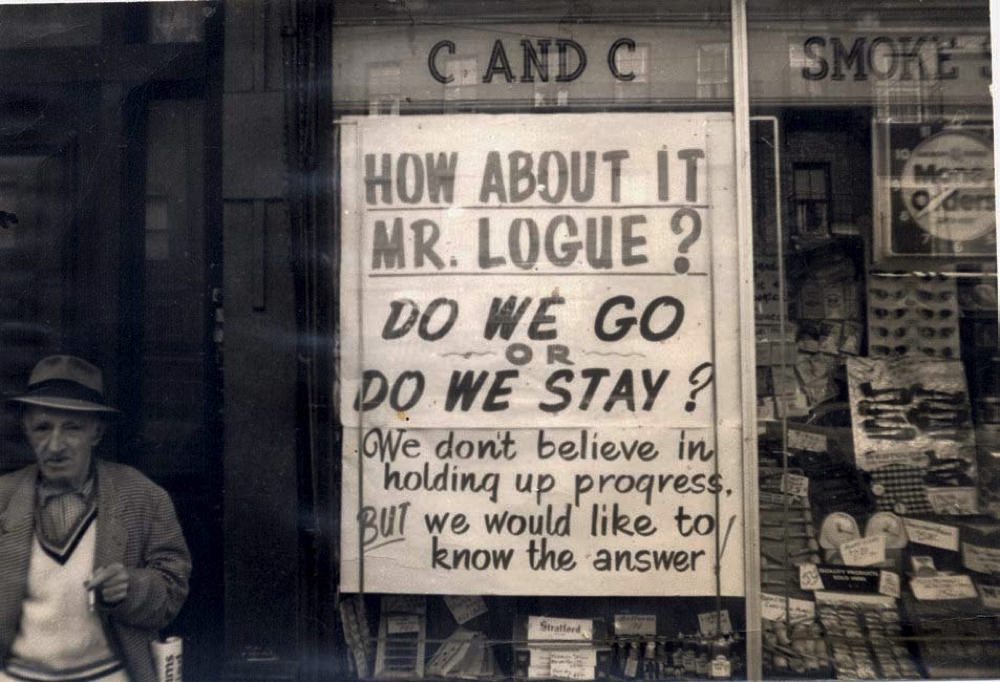

In Saving America’s Cities, Lizabeth Cohen—dean emerita of the Radcliffe Institute and Jones professor of American studies—addresses these larger questions about what people owe each other in society. She uses the life of “ ‘top city saver,’ ” “ ‘Mr. Urban Renewal,’ ” and “ ‘master rebuilder’ ” Ed Logue to tell the story of urban policy in the United States from the 1950s to the 1980s. Like Winston Groom’s Forrest Gump or Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, Logue during his working life found himself in the center of a series of major federal and state approaches to revitalizing urban areas. A controversial figure who died in 2000, he was very active in taking advantage of programs and creating new opportunities, using his skills as a negotiator to capture funds from newly approved programs and his capacity as an innovator to launch additional policy and program initiatives in three cities. Focusing most attention on the central cities of medium to larger metropolitan areas, he also dabbled in working at a metropolitan and state level. He had a lifetime commitment to racial equity, particularly notable in his hiring practices.

Development czar Ed Logue

Photograph courtesy of the City of Boston Archives

Cohen’s project is, in part, one of rescuing urban renewal from the image of “abject failure” cultivated from both the left and the right. As Cohen argues, her book “aims to present an alternative, more nuanced history of postwar American city building that does not dismiss the federal role in renewing cities and subsidizing housing as pure folly. It claims instead that there is a usable past of successful government involvement in urban redevelopment from which we can benefit today as we grapple with the current challenges of persistent economic and racial inequality, unaffordable housing, and crumbling infrastructure.”

In this history those who led urban renewal certainly made mistakes, insensitively displacing people, imposing flawed design theories, and underestimating resistance to racial inclusion. However, they learned from their mistakes and did better the next time. As Cohen argues, “Urban renewal as experienced in 1972 was far different from that in 1952.” By 1982, it had become almost unrecognizable.

The first phases of urban renewal generally included a great deal of demolition and rebuilding in single-use zones, along with innovative social programs; in later years there was more revitalization, mixed use, and human-scale design. In the early years, Logue used a pluralist, expert-led model that too often alienated neighborhoods; in later years his approach to democracy was more direct. He faced opposition throughout his work life, however, both from those not wanting to be displaced and those resisting racial and economic integration.

Logue’s major projects roughly parallel fashions in renewal and redevelopment and divide fairly conveniently by decades, and Cohen uses these periods to organize the book. Logue started in New Haven in the mid 1950s, having earlier graduated from Yale and its law school, and having worked as both a labor organizer and Connecticut labor secretary. With Mayor Richard Lee, Logue attracted “more redevelopment funds per capita than any other city received,” testing both physical redevelopment and social programs that became part of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. He was then in Boston until the late 1960s as head of the Boston Redevelopment Agency (BRA), arriving after the West End had been demolished but in time to be responsible for the swath of modernist design called Government Center. In this period he retained more historic urban fabric and engaged neighborhood groups. Recruited to New York, where he spent much of the 1970s and 1980s, he first led the innovative statewide Urban Development Corporation (UDC) under Governor Nelson Rockefeller. As the federal government retreated from developing affordable housing, Logue pioneered a new quasi-public approach, eventually creating housing for 100,000 people. In this period, he also attempted to launch a Fair Share affordable-housing project in the suburbs, suffering a difficult backlash. After the UDC experiment collapsed amid the financial and political turmoil of the mid 1970s, he had a final chapter in the South Bronx, working at a smaller scale and in a more participatory manner, finally really doing what he had long claimed to do, “planning with people.”

The book is more than a biography of Logue. Cohen spends time finishing the stories of the cities where he worked, even after he moved on. Staff colleagues in early projects later became leaders of major initiatives elsewhere, linking the personalities in Logue’s life with a larger narrative. For example, the leader of the social-development organization Logue sponsored in New Haven, Community Progress Inc., later became the first president of the Ford Foundation-sponsored Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC). Since 1979, in the wake of federal pullback, LISC has invested $20 billion sponsoring more than 400,000 affordable housing units and tens of millions of square feet of community and commercial space. The world of the Boston-Washington corridor in the 1950s to the 1970s was a small one with many interconnections among key players, and these are fully evident in the book.

Cohen’s analysis is aided by the location of Logue’s projects in university towns. Yale political scientist Robert Dahl used Lee and Logue’s New Haven as the focus for his important book, Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City (1961), and two Yale graduate students, Nelson Polsby and Raymond Wolfinger, conducted parallel work and produced books. Boston and New York also contributed their share of research on urban issues. These studies were not always sympathetic to Logue, but they provided Cohen a rich empirical base from which to work—complemented by assistance from the Logue family, approximately 80 of her own interviews, multiple oral histories and transcribed interviews with Logue and associates, and numerous archives and libraries.

As an urban planner, one of the professions low on the pecking order in urban renewal, I was of course interested in Logue’s story. Some of the contemporary debates about his work were conducted in the journal I now edit (then called the Journal of the American Institute of Planners). As a scholar of new towns, I was interested in Logue’s attempts to build them in the 1970s, even though Cohen sees Logue’s attempts more positively than I do. Importantly, beyond this planning context, Cohen makes a number of arguments that loom larger than Logue himself or even urban policy, making her history relevant to a wider audience.

Redevelopment reactions: The South End community versus the Boston Redevelopment Authority

Photograph courtesy of the City of Boston Archives

One insight is that improving communities with multiple disadvantages is no small task—and the goalposts are always shifting, as Cohen’s detailed narrative makes vividly clear. Reformers like Logue certainly learned from experience and shifted their approach. But the world around them changed constantly, so even a program or policy successful in one period was not viable in another. Places had changed physically and socially compared to earlier rounds of renewal, residents had different expectations, businesses assumed different roles, and the federal government changed strategies and generally scaled back its financial and policy commitments. With less federal attention, state and local governments, and an increasing number of nonprofit agencies, stepped in. But they brought different interests and experiences to urban renewal. This is why improving urban areas is so difficult—and why urban planners have moved to emphasize developing processes for improving communities.

Another large question is the role of experts in defining problems, proposing solutions, and working toward justice. Cohen proposes that “as Logue learned from hard experience over his career, the fate of cities cannot be left solely to top-down redevelopers or government bureaucrats or market forces or citizens’ groups. Rather, the goal should be a negotiated cityscape built on compromise.” One part of this negotiation is about good design. Logue began his career attracted to stripped-back modern design, but over time came to embrace rehabilitation and designs that, more than early modernist experiments, signaled a sense of home to their prospective residents. Cohen richly describes the various places and projects Logue worked in and on; as I read I found myself gravitating to my computer where I could find images, zoom in to maps, and search recent aerial photography of the communities today.

Cohen’s overriding interest lies in the possibilities for social reform. The programs she examines and people associated with them defy easy categorization. There were liberals and conservatives for urban renewal and against it, depending on the context. Logue himself embodied contradictions: he was an often difficult person and a committed social reformer, a design modernist and a pragmatist, a strongly principled person willing to push the boundaries of programs for the greater good. Today, when inequality is on the rise, Saving America’s Cities warns against easy solutions while offering hope that people can improve the places where we live—and with that, people’s lives.