On August 28, 1919, William Monroe Trotter, A.B. 1895, sat before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations to urge inclusion of the “rights of colored people” in the U.S. peace treaty with Germany. He spoke for the Liberty League, which he helped found in 1917 in the spirit of the political activism and militant protest that spread across the African diaspora during and after the Great War; the league sought political equality for African Americans and a “guarantee of self-determination for darker nations” across the globe. Using the league’s language of black liberation, Trotter demanded the following change to part 16 of the treaty: “In order to make the reign of peace universal and lasting, and to make the fruits of the war effective in the permanent establishment of true democracy everywhere, the allied and associated powers undertake, each in its own country, to assure full and complete protection of life and liberty to all the inhabitants, without distinction of birth, nationality, language, race, or religion, and agree that all their citizens, respectively, shall be equal before the law and shall enjoy the same civil and political rights without distinction as to race, language, or religion.”

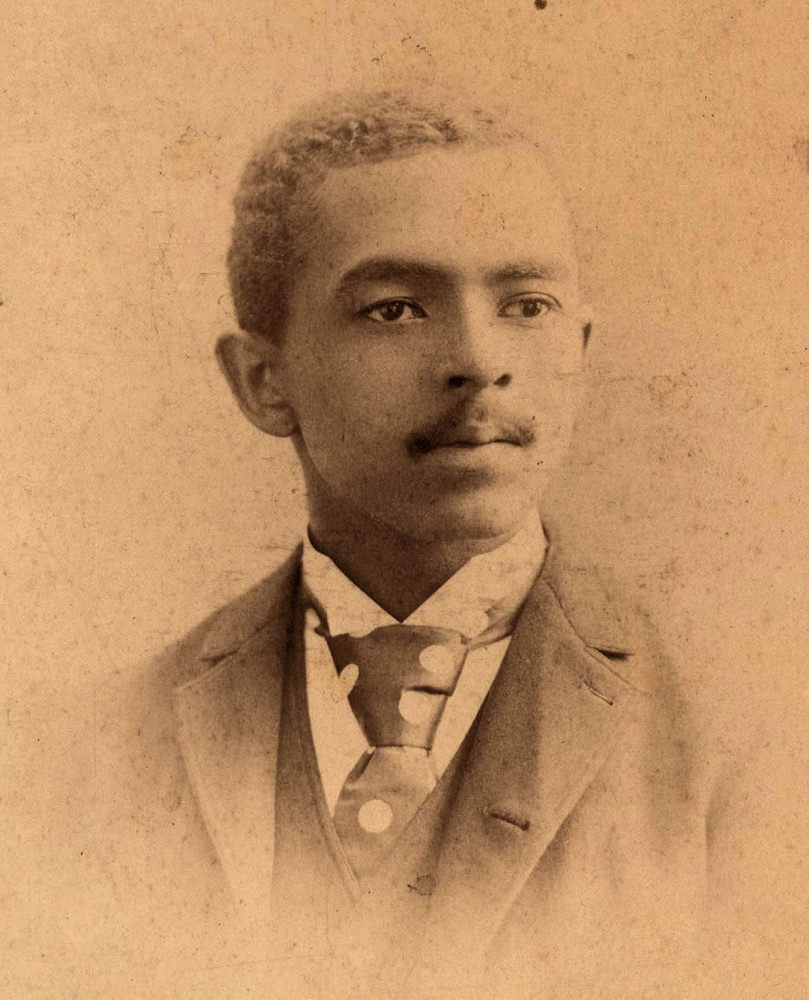

William Monroe Trotter as a high-school senior

Photograph courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

By then, Trotter had been a radical newspaper editor and activist for nearly two decades. He was part of W.E.B. Du Bois’s “talented tenth”: his father was a Union Army officer, real-estate investor, and federal appointee, and his mother a descendant of free artisans and landholders in Charlottesville, Virginia; he was raised just south of Boston, in the town of Hyde Park. At Harvard, where Trotter never ranked lower than third in his class of 321, he started the first Total Abstinence Club (to curb student drinking) and led his first protest—against segregated barbershops in Cambridge.

In founding the Boston Guardian newspaper in 1901, Trotter was determined to use his relative privilege to challenge the denial of civil rights and the proliferation of anti-black violence that flourished in Reconstruction’s aftermath. The Guardian’s goal, he said, was to do as “the press ought to do: hold a mirror up to nature” by exposing the consequences of white supremacist policy. As Supreme Court rulings weakened the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and southern states rewrote their constitutions to segregate, disenfranchise, and marginalize African Americans, Trotter invoked the militancy of antebellum radical abolition to fight back. With 90 percent of southern blacks disenfranchised, and northern blacks being told the Republican Party was “the ship and all else the sea,” he forced northern, enfranchised, and “thinking members” of his race to “agitate, agitate, agitate” for rights being denied through federal neglect, counseling readers and supporters that “Only the colored people themselves can determine their political, social, and economic future.”

In Massachusetts, Trotter used the Guardian to confront white progressives who insisted “the Negro” was a southern problem, that New England’s abolitionist history absolved it of racial sin. In 1902, for instance, he organized massive protests against the extradition of a North Carolinian, wrongly accused of insubordination and arson, who had fled to relatives in Massachusetts and sought help from Boston’s black community. The Guardian-promoted effort failed, but highlighted white ignorance of, and reluctance to acknowledge, racial injustice in the Jim Crow South.

Even as many leaders, both black and white, insisted that slavery, Reconstruction, and blackness itself rendered African Americans “incapable of intelligent and reasonable democratic engagement,” in the words of film director D.W. Griffith, Trotter organized what contemporary political pundits called the “New England example”—black communities using their power as swing voters to elect “principles, not parties.” In 1915, he relied on this strategy to launch a national protest against Griffith’s racist film Birth of a Nation. By 1920, black voters in Michigan, Ohio, New York, New Jersey, and New England consistently voted with the Democratic party, not with the Republicans, in local and state elections.

Trotter had become “the stormy petrel of the times,” declared the black radical magazine publisher and editor Cyril V. Briggs: “the most significant voice of radical Negroes (for the man on the street anyways) in a generation.” Radicals across the African diaspora had donated money for his trip to Paris for the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, where he presented the Liberty League’s demands to the French public.

The trip cemented Trotter’s role as the populist hero of the black working class. He returned from Europe determined that “the colored people of the world” define democracy and freedom on their own terms. Throughout the 1920s, he continued his crusade against Boston’s segregated public hospital, supported congressional efforts to pass an anti-lynching bill, and founded the African Blood Brotherhood, to mobilize armed black self-defense against racial violence. But newer black weeklies like the Chicago Defender were eroding the Guardian’s popularity, its viability already sapped by the death in 1918 of Trotter’s activist wife, Geraldine “Deenie” Pindell Trotter, whose editing and bookkeeping skills had helped sustain it. By the early 1930s, Trotter was broke, and many of the causes for which he’d fought seemed lost. He jumped to his death from a Boston apartment building the morning he turned 62.

Radical activists across two generations were inspired and challenged by Trotter and the black Boston politics he cultivated. At a time when the black press was owned and operated by racial conservatives, black and white, who stifled black dissent for the sake of white comfort and racial respectability, Trotter galvanized black working people to recognize and embrace their political power.

Updated 3-3-20: A reporting error resulted in the initial publication of an incorrect caption and credit for the group photograph above. We regret the error and thank Dr. Jeffrey B. Perry for calling it to our attention.