A Harvard-led consortium of Boston-area healthcare, biotech, and biopharma institutions will open a $50-million nonprofit facility for the development of cell- and gene-based therapies, the University announced today. The hope is that the center will make it easier and more cost-effective for biomedical researchers to develop these new treatments—which represent the cutting edge in the fight against cancers, autoimmune conditions, and other diseases—and see them through clinical trials and eventual FDA approval.

“The types of therapies that this facility will focus on are among the most promising candidates for therapy…, and many of these therapies are at very, very early stages,” said Harvard provost Alan Garber, who is also a healthcare economist and physician. “What we are creating here is not a manufacturing facility, like a major pharmaceutical or biotech company might create. It is designed to be able to produce therapies that could be used for relatively small-scale trials....This is the kind of facility that can be used to accelerate the transition from laboratory to approved therapy.”

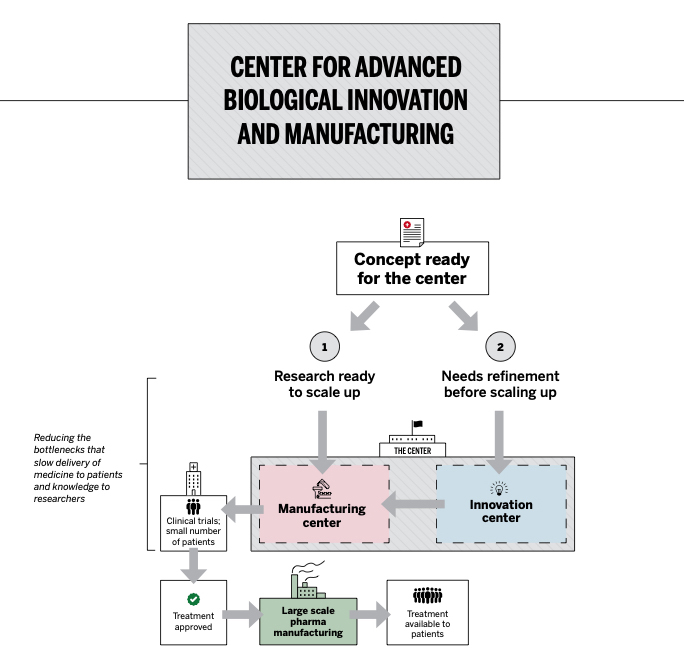

Illustration courtesy of the Harvard Gazette

Along with Harvard, the founding members of the consortium include MIT, General Electric Healthcare Life Sciences, Alexandria Real Estate (which focuses on developing labs and offices), and Fujifilm Diosynth Biotechnologies. Five Harvard-affiliated hospitals—Brigham and Women’s, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston Children’s, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center—as well as MilliporeSigma are also part of the group. The state government has been “an enthusiastic participant” in conversations with the consortium but has not yet committed to a financial contribution, said Kevin Casey, Harvard’s associate vice president for public affairs and communications.

The impetus for the center came after Harvard and leaders from other life-sciences institutions discussed how they could work together to ensure Massachusetts remains a leader in biomedicine. Biomanufacturing—which encompasses a new class of therapies that use biological materials like cells and genes from the patient’s own body to cure diseases—emerged from those conversations as a critical research area that is difficult for scientists in academic labs (as opposed to big drug companies) to develop for treatments and then shepherd through Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

During the past five years, the number of clinical trials for interventions such as CAR-T cell therapy, which has shown very promising results in treating certain cancers that have not responded to traditional treatments, has proliferated. But lack of access to the highly technical tools and materials needed to develop these therapies has created a bottleneck, the consortium founders say. The new facility, Garber said, will be “designed to address a gap that we’ve heard is the most important gap in our region over and over again: how to support early-stage research in biological therapies.”

“MIT has a deep bent in this space of cell and gene therapy and innovation,” said Krystyn Van Vliet, MIT associate provost and professor of materials science and engineering. “But we haven’t had a place to easily work with others....Part of MIT’s deep interest in this is the manufacturing innovation: how to make medicines better, not just how to make better medicines. That is what this facility can enable: making drugs more quickly, making drugs more safely, making drugs that actually move through regulatory review to make an impact on patients.”

From the patient’s perspective, treatments such as CAR-T cell therapy are extraordinarily expensive: on the order of $500,000, and often not covered by insurance. At an August conference on regenerative medicine, Harvard Kennedy School healthcare economist Amitabh Chandra said, “We don’t have a single-payer system and it’s not clear who will pay for any of these treatments. When the payer struggles to pay for a treatment, future manufacturers get the message that even if they build it, no one will be able to pay for it. This will lead to under-investment.”

Part of the high cost of these personalized therapies is driven by their reliance on unique assessments of an individual patient’s condition, so they are difficult to scale. Traditional medicines may use molecules that are made in a lab and put into a capsule, but biotherapies are made by repurposing biological matter like immunological cells or pieces of RNA. In CAR-T cell therapy, which is FDA-approved for treating some types of leukemia and lymphoma, T cells are taken from a patient’s blood and genetically modified to express chimeric antigen receptors (CAR). Then millions of these CAR-T cells are produced and infused back into the patient to attack the cancer cells.

“These therapies are very labor-intensive, so the goal is also to make sure there is innovation around automation and simplification of the process” to cut costs, said Emmanuel Ligner, president and CEO of GE Healthcare Life Sciences. Other innovations that could make the therapies cheaper to produce include things like “off-the-shelf” CAR-T cells—still in early stages of research—that could use donors’ own T cells to treat patients. “Part of the goal is to think about innovation where you could take out my blood and cure everyone’s cancer,” said Rick McCullough, Harvard’s vice provost for research and a professor of materials science and engineering.

The planned center will be built into an existing life-sciences facility in the Boston area with 30,000 to 40,000 square feet of space, and the consortium hopes to open it by the end of 2021. One side of it will comprise cleanrooms for manufacturing therapies for clinical trials, and the other will provide space for researchers to refine ideas that are not yet ready for trials in patients.

The consortium will hire an executive director who can begin recruiting leadership staff; 40 or more employees will be hired for the facility initially, Casey said. It’s hoped that the center will also be a key source of workforce development for the skills needed to produce these new therapies. “The supply network and the talent pipeline have to be built in real time,” said Van Vliet. “As some of these therapeutics become successful...you need a workforce, a supply network. To provide this to patients in the U.S., you really need to create an ecosystem of talent, people who know how to manufacture this type of medicine.”