On November 20, 1960, scientist Mary Ingraham Bunting unveiled her vision for the Radcliffe Institute for Independent Study. Newly appointed as Radcliffe’s president, she made her announcement just weeks after the country had elected John F. Kennedy ’40, LL.D. ’56, its youngest president. Change was in the air, but Bunting was one of the foresighted few who realized women should be part of that changing equation. To provide an intellectual lifeline to talented women whose careers had been sidetracked by marriage and children, she proposed creating an institute where fellows would receive office space, access to Harvard’s resources, and a part-time stipend to pursue their creative and scholarly work. Nothing like this had ever been proposed before, certainly not at Radcliffe College. Even Bunting referred to it as a “messy experiment.”

Practically as soon as the program was announced, inquiries started to roll in. Prospective applicants were typically Boston-area women in their thirties and forties who were married with small children. After a rigorous selection process which looked both for evidence of past achievement (such as an advanced degree) and the promise of future distinction, 24 women (four more than originally planned) were offered slots in the inaugural class. When they assembled at 78 Mount Auburn Street in September 1961, they were keenly aware of the high expectations placed on them to fulfill Bunting’s expansive mission statement. But mainly they just felt lucky to have been chosen.

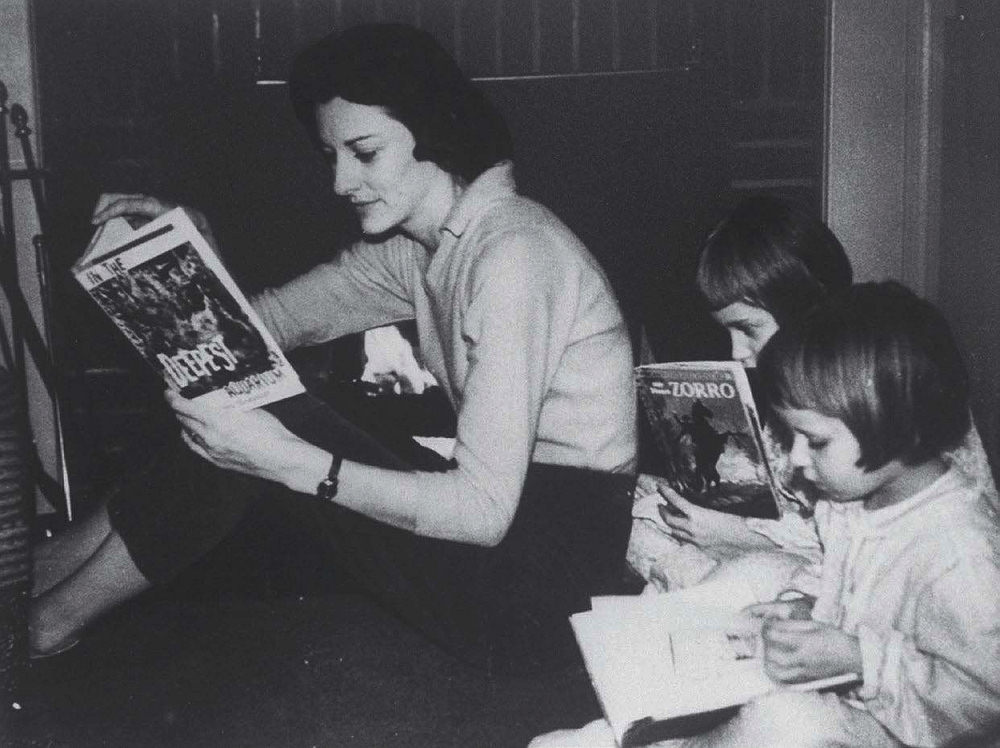

Anne Sexton with her daughters, Linda and Joy, 1962

Photograph by Ian Cook/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images/Getty Images

In The Equivalents: A Story of Art, Female Friendship, and Liberation in the 1960s, Maggie Doherty, Ph.D. ’15, a literary scholar and critic, and a preceptor in Expository Writing, tells the story of how this small and privileged group “operated as a hinge between the 1950s and 1960s, between a decade of women’s confinement and a decade of women’s liberation.” Her chosen vehicle is collective biography, focusing on three women from the inaugural class and two from the second class: poets Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin ’46, A.M. ’48, artist Barbara Swan, writer Tillie Olsen, and sculptor Marianna Pineda. These women formed a friend group which they called “the equivalents”—a humorous but self-conscious reference to the requirement that fellows have an advanced degree or its equivalent. Sexton and Kumin were already close friends and writing collaborators who had met in Boston’s male-dominated poetry circles in the 1950s, a relationship they concealed from the selection committee. Swan and Pineda had also already connected, although not as deeply, as two creative artists living and raising children in Brookline who felt somewhat out of sorts with the general domestic scene in that affluent suburb. The odd person out was Olsen, who relocated from the West Coast to take up her fellowship.

The choice of these five to anchor the book was felicitous. (In a footnote Doherty gives a shout-out to Sexton biographer Diane Middlebrook for first noticing the existence of this quintet.) Sexton, Kumin, Swan, and Pineda all came from fairly privileged backgrounds and were now comfortably ensconced as married if somewhat restless white women in affluent Boston suburbs. Even if they didn’t need the money (the stipend was not need-based and would not have replaced a full-time salary if any of them had been employed), they treasured the validation it gave to their professional aspirations. Like many of the other early fellows, they used their stipends to hire household help and other domestic support to make it possible for them to devote more time to their creative work—not seeing the irony of hiring other, less privileged women at low wages to shoulder those chores. Doherty prominently foregrounds this initial blindness to class and racial privilege, pointing out that the institute, like many other women’s educational reforms of the era, was framed “as a gentle corrective to a life course that was already moving in the right direction,” rather than a challenge to the barriers that kept many women from getting on that track in the first place.

If these four women very much reflected a certain definition of “women of talent,” Olsen helped Radcliffe broaden its view. She was a working-class radical activist whose well-received short stories and essays in the 1930s had given her hope that she could become a writer. But she lacked the financial resources to pursue that dream and was forced to hold low-level jobs while she tried to keep her family afloat, effectively silencing her as a writer. The Radcliffe fellowship offered her the opportunity to find her voice and start writing again. Even though Olsen was not able to write the novel she hoped during her fellowship years, she formulated the book that became Silences (1978), a foundational text of early feminist criticism. Throughout Doherty’s narrative, Tillie Olsen provides a radically different—and welcome—point of view. For example, while Maxine Kumin was “mad for the message” of Betty Friedan’s just published The Feminine Mystique in 1963, Olsen quickly realized it had little to say to working-class women like herself who were trapped not by domesticity but by the need to pay the rent.

In addition to the five Equivalents, the book features a large cast of supporting characters, fascinating women in their own right, such as Bunting, Sylvia Plath, Alice Walker, BF ’72, Florence Howe, and Adrienne Rich ’51, Litt.D. ’90, who interact with the main players and also allow connections to events beyond the Radcliffe Institute in its early years.

But any reader who picks up the book will immediately realize that the Anne Sexton-Maxine Kumin friendship provides its narrative backbone and emotional core. In many ways, this is a wise decision, since the two women are charismatic characters who offer an intimate glimpse into how the institute nurtured their creative process. The rich sources available to document that influence are also a huge plus—especially the sound recordings of their seminar talks preserved in the institute’s archives at the Schlesinger Library. But at times this focus threatens to take over the story, especially as Sexton tries to navigate her struggles with mental illness. Sexton’s eventual suicide in 1974 looms large, essentially supplying the book’s end except for a short epilogue.

The Equivalents is most successful when it keeps close to the story of its five main protagonists. It captures the joy of their mutual friendships and how they depended on each other for encouragement and support: “a fleeting window on women’s camaraderie and autonomy in a society not designed for such things.” The writers read and critiqued each other’s work, and Barbara Swan created a series of drawings of the original fellows, several of which appear in the book. Later she supplied cover art for books by both Sexton and Kumin, even though she had moved on to lithography. Why? “I just did it out of friendship.” As Swan realized, these deeply felt relationships shaped and informed the artistic work the Equivalents created while at Radcliffe. Case in point: the sculpture that Marianna Pineda donated from her Aspects of the Oracle series in honor of Connie Smith, the beloved first director of the institute who died young from cancer. That sculpture still holds pride of place in Radcliffe Yard.

When Doherty wanders too far from her collective biography, however, she sometimes loses her way. Her description of the 1950s domesticity which had thwarted the lives of so many talented women sets the stage for the creation of the institute in the first place, but her attempts to link the initiative to the broader history of feminism that comes later are less convincing. Doherty does seem to realize the limits of how far she can stretch her story: “The sad irony of the Equivalents is that the movement they helped give birth to was not one in which they could participate fully,” she writes. “The Equivalents were women born too early; by the time the women's movement gained full steam, each of them was well established in her life and ways.”

And yet there is something wonderfully bracing about learning about this key moment in Radcliffe history and thinking about what has happened in the almost 60 years since. Thousands of women—and since 1999, small numbers of men—have had life-changing opportunities for a year at Radcliffe, surrounded by the company of an increasingly diverse set of artists, writers, and academics. Long gone are the days when the institute catered mainly to local women who were primarily white and comfortably middle-class; now its reach is truly global. Surveying this transformation, we have reason to thank Mary Ingraham Bunting for setting out to challenge the “climate of unexpectation” that she identified as holding back American women, and by extension, American society, in the domestic-bound 1950s. And we have Maggie Doherty to thank for bringing this story, warts and all, to new readers who are left contemplating what “messy experiment” we should be considering for our own perilous times.