Intimidating, stoic, yet somehow accessible, Nobel laureate and novelist Toni Morrison, Litt.D. ’89, emerges from the white background of a painting by contemporary portraitist Robert McCurdy. According to a new exhibition catalogue published by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, when former Guggenheim Museum director Lisa Dennison first laid eyes on the portrait, she exclaimed: “It’s God herself.”

Morrison stares from the cover of the VISIONARY: The Cumming Family Collection catalogue, which contains life portraits of more than two dozen presidents, business billionaires, revolutionary scientists, Supreme Court justices, generation-defining writers, and eight Nobel Prize winners—created by artists who transformed portraiture in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. At once revivals of and challenges to artistic tradition, the portraits give intimate access to people who shaped contemporary society, an ambition rarely seen in private art-collecting today. All were commissioned or acquired across more than 25 years by the late Ian Cumming, M.B.A. ’70, the Leucadia National Corporation (now Jefferies Financial Group) co-founder who scrupulously avoided public attention and photographs of himself and his wife, Annette.

Since Ian Cumming’s death in 2018, the Cumming family has gifted or promised 22 portraits from its collection to the Portrait Gallery. Given the museum’s relatively small annual acquisitions budget of around $250,000, “We could never have afforded to have bought them, or even to have commissioned them,” says director Kim Sajet. Congress mandates that the Portrait Gallery showcase individuals important to United States history and culture, so all the portraits depict Americans—with the exception of British primatologist Jane Goodall, whose institute is headquartered in Virginia.

How did a publicity-shy businessman convince such celebrities as Goodall, Bill Clinton, Nelson Mandela, LL.D. ’98, and the fourteenth Dalai Lama to sit down for portraits? Or moonwalker Neil Armstrong, notoriously reticent about sharing his likeness?

Enter D. Dodge Thompson, M.B.A. ’80, a distant Cumming relative by marriage and longtime chief of exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art. Cumming had spun his Harvard Business School training into Leucadia, a conglomerate nicknamed “Baby Berkshire Hathaway” for investing in undervalued stocks with great success. (Forbes named him one of the 400 richest Americans in 2008.) At a family reunion in 1994, Thompson proposed an idea: commissioning portraits of people whose contributions to civilization would be remembered in 100 years.

At that time, parts of the art world found portraits passé, but Thompson had observed that “portraits were still among the most skillful” of the works hanging in the National Gallery and “elicited the most response” from visitors. Even so, influential people “rarely got a good artist to do their portrait in their lifetime.”

I.M. Pei, 1996 by Richard Estes

Cumming agreed. The first candidate Thompson approached was former Harvard biology professor James Watson, whose Nobel-winning work on DNA revolutionized science and medicine. Watson agreed to the portrait—then chose artist Jack Beal without consultation. The 1995 result struck Thompson as somewhat wooden or contrived, a departure from the artist’s usual lively and seamless work, and he vowed to pair portraitists and subjects before making requests. “I wanted to match the sitter and an artist who had a particular affinity, but not necessarily a recognized affinity—hence, getting Richard Estes, who does so much in architecture but almost no portraits, to have a go at I.M. Pei [M.Arch. ’46, Ar.D. ’95],” the iconic architect and briefly Harvard Graduate School of Design assistant professor.

Gregarious yet contrarian, Cumming shifted commissioning preferences based on mood and feelings of financial security. (The catalogue notes his fondness for declaring his tombstone should read “often wrong but never in doubt.”) But he consistently sought portrait subjects whose work in environmentalism, social justice, and art altered the world.

The Four Justices, 2012 by Nelson Shanks

© Estate of Nelson Shanks/National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Gift of Ian M. and Annette P. Cumming

Landmark judicial decisions certainly qualified the only four women to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court. After Annette Cumming pointed out that men far outnumbered women in the collection, an idea struck Thompson: reimagining seventeenth-century Dutch paintings of the regentesses of St. Elisabeth’s Hospital in Haarlem—some of the earliest women to be portrayed as secular leaders in Western European art—with Sandra Day O’Connor, former Harvard Law School dean Elena Kagan, J.D. ’86, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, LL.D. ’11. He recruited Nelson Shanks, an artist steeped in Renaissance and Baroque portraiture traditions and known for conveying the inner lives of subjects.

Viewing the Four Justices

Photograph by Tony Powell, 2019. National Portrait Gallery

In 2013, the Portrait Gallery installed the approximately seven-foot-tall painting on loan, and after conversations with Mrs. Cumming, who saw it as an exciting educational tool, the museum arranged to interview the justices and then posted the videos online. The painting and interviews teach young people that “there are some people that have been there before you that have also struggled, and now their portraits are in the Portrait Gallery,” says Sajet, herself the museum’s first woman director. She often spots girls taking selfies with the painted justices.

Approaching subjects “got easier and easier as we had a repertoire or an inventory of sitters. That gave us bona fides,” Thompson recalls. Personal connections sometimes helped, as happened with Pellegrino University Professor emeritus and pioneering environmentalist E.O. Wilson S.D. ’04. “I wasn’t even counting how many portraits there were,” says Thompson, until the Cumming home began running out of wall space.

After her husband’s death, Annette Cumming, a thoughtful and no-nonsense former nurse, spearheaded arrangements for the collection. An April exhibition was supposed to feature the gifts and pledges, plus portraits of foreign figures still held by the Cumming family (including Nobel laureates Gabriel García Márquez and Desmond Tutu, LL.D. ’79), and portraits promised or donated elsewhere. The COVID-19 pandemic shuttered the Portrait Gallery in March, but the work of chief curator Brandon Brame Fortune, who curated the exhibition, is on display in the catalogue she wrote with Thompson (available from the department of publications while the museum shop is closed).

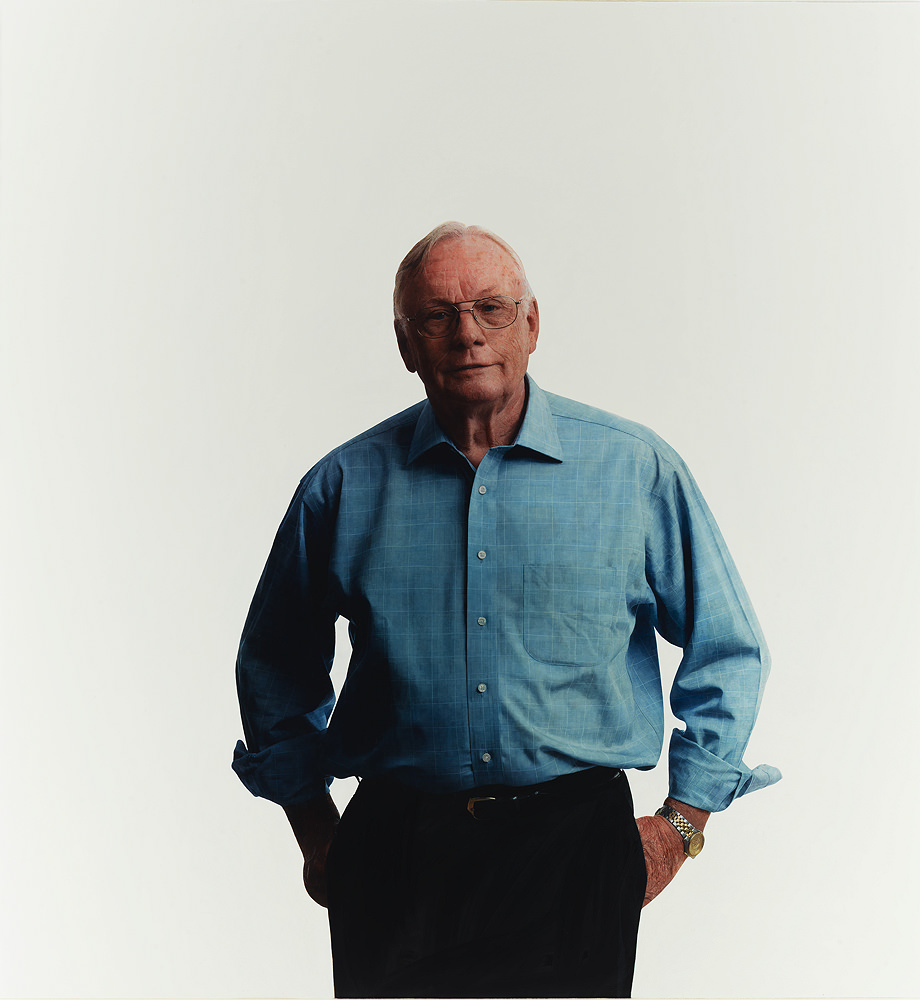

The Cumming portraits fill gaps in the museum’s collection—Morrison, legendary musician Mstislav Rostropovich, Mus.D. ’74—and depict American icons like Muhammad Ali and Neil Armstrong long after their heyday. “We often fix someone in time. Neil Armstrong, we only know him from 1969,” says Thompson. In the Robert McCurdy portrait, we see an older Armstrong, a private citizen in a plain work shirt.

Neil Armstrong, 2012 by Robert McCurdy

© Robert McCurdy/National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Gift of Ian M. and Annette P. Cumming

McCurdy has painted a dozen portraits for the Cummings in his signature larger-than-life photorealist style, with more planned. Conceptually, McCurdy’s work “both denies and engages with celebrity, in that he asks his subjects to stand quietly while he photographs them and to empty their minds,” says Fortune. (Recently, Jeff Bezos selected McCurdy to paint his portrait, commissioned by the Portrait Gallery for its own collections.)

Pushing even further conceptually, Chuck Close, who transformed twentieth-century portraiture, accepted the first-ever commission of his career in 1997 to paint artist Jasper Johns for the Cummings, followed nearly a decade later by Bill Clinton. From 50 feet away, a Close portrait “looks photorealist, and then you come up, and oh my god, it’s so abstract,” says Thompson. A lifelong Democrat, Ian Cumming also acquired wall-size Close tapestries of Barack Obama, J.D. ’91, and Al Gore ’69, LL.D. ’94.

Like several people involved in the project, Close has a complicated legacy. “I was very conflicted when women stepped forward to say that he had harassed them,” says Thompson. “Bill Clinton similarly.” James Watson was forced to retire after suggesting that black people had inferior intelligence. E.O. Wilson’s sociobiology sparked fierce debate for extending evolutionary theory to human behaviors like warfare. The catalogue touches such controversies within strict word limits. “There’s no moral test to be in the Portrait Gallery,” says Sajet.

John Ashbery, 1984 by Alex Katz

© 1984 Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Gift of Ian M. and Annette P. Cumming

To his surprise, Thompson discovered that 15 of the Cumming subjects taught, studied, or received honorary degrees at Harvard. Those not yet mentioned are Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes, LL.D. ’83, Nobel-winning Peruvian writer and former Harvard visiting professor Mario Vargas Llosa, Litt.D. ’99, former World Bank Group president James Wolfensohn, M.B.A. ’59, and perhaps the most influential late-twentieth-century U.S. poet, John Ashbery ’49, Litt.D. ’01.

Sajet, who has completed HBS nonprofit leadership training herself, thinks the attributes required for collecting portraits—patience, trust, team-building, deep appreciation for people—likely made Ian Cumming a successful business leader. “If he had five minutes with somebody in an elevator, I’m sure he probably became their friend,” she says. Thompson says he and Cumming believed their HBS classmates were their collaborators, not competitors.

Facing a pandemic, Thompson has drawn on other HBS lessons, such as how to handle several projects simultaneously. He typically works on 55 to 65 exhibitions at once, and many now face difficult rescheduling challenges. At the Portrait Gallery, Sajet is grateful that, unlike numerous John Singer Sargent drawings sitting in the dark after being displayed for only two weeks, with the clock ticking to return them to lenders, the Cumming gifts are here to stay. “We will show them, we’re just not quite sure when,” she says.

As museums turn to digital programming—3-D virtual tours, storybook readings, art classes—Sajet thinks a second, more sustainable phase is coming: “People are dying to get away from their screens.” She imagines some programs will stick, like online master classes for people who could never visit the museum. But there is much to rethink: gallery touch tables that force interaction between visitors, the safety of art handlers who must work in small groups to install each piece. “You can’t social distance and hang a painting,” she says.

Thompson, Sajet, and exhibition curator Fortune feel confident visitors will return, eventually, for what can’t be experienced online. “When you come face to face with Toni Morrison, who’s 50 percent larger than life, and you can read every line on her face like a beautiful map of the countryside, I think there is a real poignancy there,” says Thompson. “I think people will come back time and time again.”