•The endowment’s value was $41.9 billion as of this past June 30, the end of fiscal year 2020—an increase of $1.0 billion (2.4 percent) from $40.9 billion a year earlier.

•Harvard Management Company (HMC) recorded a 7.3 percent return on endowment assets during fiscal 2020: up from the 6.5 percent return recorded during the prior year. (The return figures take investment expenses and fees into account.)

•Among other institutions with similar investment strategies that have reported results, the perennially outstanding MIT earned an 8.3 percent return on its pooled investments, and the value of its endowment rose 5.4 percent to $18.4 billion (excluding pledges). Yale reported a 6.8 percent rate of return, and its endowment increased 2.7 percent in value, to $31.2 billion.

•Today’s results are just the headline, aggregate figures. HMC president and CEO N.P. Narvekar provided this succinct comment:

As we continue to make progress in the five-year transition of HMC and our investment portfolio, we are mindful that there is much left for us to accomplish. Our team remains confident that the changes being made to both the portfolio and the organization’s systems, structure, and culture will serve the university well and generate the long-term returns on which Harvard relies.

HMC defers detailed reporting on its investment returns by asset class, and other performance metrics; they are released with the University’s annual financial report for the fiscal year, typically published in late October. Check back at www.harvardmagazine.com for a comprehensive report on the fiscal 2020 HMC data and Harvard’s finances, when those become public.

•Based in part on the returns, President Lawrence S. Bacow, Provost Alan Garber, and Executive Vice President Katie Lapp informed the community today that $20 million in central funds would be distributed to the schools and affiliated institutions to help them cope with the enormous costs of operating while containing the coronavirus pandemic.

As always, the change in endowment value reflects three intersecting factors:

- the investment return (positive this year);

- the regular distribution of funds—a withdrawal from the endowment, to support Harvard’s operations—and possibly other one-time distributions, so-called decapitalizations; and

- the gifts added to the endowment, as pledges are fulfilled and proceeds received—the fruits of The Harvard Campaign, concluded June 30, 2018—and any subsequent gifts for endowment made in time for inclusion in fiscal 2020 results. (Harvard includes pledges in the endowment total it reports—$1.5 billion of the $40.9 billion as of the end of fiscal 2019; some other institutions, including MIT, exclude pledges from the endowment values shown in their financial reports.)

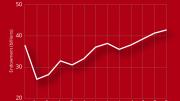

The Endowment’s Value

HMC, which invests the University’s endowment and other financial assets, announced today that during fiscal 2020, the endowment’s value increased 2.4 percent, to the reported $41.9 billion; during the prior year, its value had appreciated 4.3 percent, to the reported $40.9 billion. Thus, in absolute terms, the endowment’s value increased $1.0 billion during the fiscal year just ended (not adjusted for inflation). It is the growth in real, inflation-adjusted value over time that determines how much the University can increase spending on its academic mission (hiring faculty members, providing financial aid, running libraries and laboratories, etc.).

The change in the value of the endowment reflects the intersection of:

Appreciation. HMC’s money managers—primarily external investment firms—achieved an aggregate 7.3 percent investment return (realized and unrealized; after all expenses), producing an increase in value of perhaps $3.0 billion. (Transfers and timing differences—when funds are received and disbursed—figure in the final rate-of-return calculation and reported endowment value; exact figures await publication of Harvard’s annual report later this autumn, as noted.)

Distributions. Harvard’s endowment exists to provide a permanent source of capital, investment earnings from which funds can be distributed to pay for University operations. Such distributions reduce the endowment’s value. In fiscal 2019, those distributions, slightly more than $1.9 billion, accounted for 35 percent of the funds used to operate Harvard—by far the largest source of revenue. The comparable figure for fiscal 2020 again awaits publication of the annual financial report, but the distribution (as determined by the Harvard Corporation) likely grew from the prior year.

As reported previously, in light of weak investment returns earlier in the decade, the Corporation held the distribution flat (per unit of endowment owned by each school) for fiscal 2018, and suggested that distributions could increase within a range of 2.5 percent to 4.5 percent annually for fiscal 2019 through 2021 (the first year of the new University presidency, and during HMC’s continuing strategic transition—but see below for discussion of the lower distribution for the current fiscal year, 2021); it also announced that distributions per unit would increase 2.5 percent in fiscal 2019—and subsequently continued on that trajectory for fiscal 2020. The number of units each school owns changes (as they receive gifts or transfer funds into their own endowment accounts), so the absolute dollar sum distributed to them typically rises more than the percentage change in the per-unit distribution rate each year.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation therefore suggests that funds distributed in fiscal 2019 increased by perhaps 4 percent to 5 percent in fiscal 2020, bringing the total to roughly $2.0 billion in the most recent year, being reported in summary form today.

Gifts. The value of the endowment is augmented by capital gifts received each year: fulfillment of pledges made during prior years (as in The Harvard Campaign), and other capital funds given during the current year. At the end of fiscal 2018, some $936 million in outstanding pledges for endowment gifts were reported in Harvard’s financial statements—a sum that surprisingly increased to $1.5 billion by the end of fiscal 2019, fueled by several large gifts during the first year of Lawrence S. Bacow’s presidency. Knowing the flow of pledges fulfilled versus new ones received must await publication of the University financial report; for now, as an estimate, assume that gifts received for endowment during fiscal 2020 totaled a relatively nominal $100 million or so, compared to more than $600 million annually in each of the prior two years.

Thus, the rough calculation (in rounded numbers) would be:

- $40.9 billion beginning value as of July 1, 2019,

- plus $3.0 billion (fiscal 2020 investment gains),

- minus $2.0 billion in operation distributions for the University budget (with no estimate made for nonoperating “decapitalization” distributions),

- plus perhaps $100 million in gifts for endowment received,

- equals the endowment’s reported $41.9-billion value as of this past June 30.

The Endowment in Context

The year ended June 30 was a confounding one for many institutional investors. Reflecting the extreme volatility in investment markets—public securities markets plunged during the late winter and early spring during the coronavirus pandemic and economic shutdown, and then soared in response to enormous fiscal and monetary support programs—the Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service (which monitors endowments and pension plans) reported a median return of 11.07 percent for the quarter ended June 30, but just 3.36 percent for the fiscal year ended then.

It noted that gains were driven by holdings of U.S. stocks, in which large endowments, like Harvard’s, are typically under-invested; larger endowments’ preference for alternative and less liquid investments (such as private equity, real estate, natural resources, and various kinds of hedge funds) may have penalized their recovery and performance for the pandemic period—and indeed for the entire year. Fixed-income assets (bonds), another class in which smaller endowments are more heavily invested than larger ones (Harvard’s position is about 6 percent of endowment assets), also performed very strongly, given the worldwide reduction in interest rates. CalPERS, the huge California public employees retirement system, an early reporter with the whole range of assets in its portfolio, logged a preliminary 4.7 percent investment return for the fiscal year.

Among others reporting, the University of Pennsylvania’s Office of Investments recorded a 3.4 percent return, and Dartmouth achieved a 7.6 percent return; both schools’ endowments are smaller, and employ different strategies, than Harvard, MIT, Yale, and their immediate financial peers. The University of Virginia Investment Management Company (UVIMCO) had a 5.3 percent investment return for the fiscal year. Its diversified portfolio, for which there are already detailed results by asset class, earned a 6.0 percent return on public equities, 9.9 percent on equity hedge funds, and 14.8 percent in the private-equity portfolio. Virginia’s real-estate (negative 4.2 percent) and natural-resources (negative 27.6 percent) assets produced losses. But the stand-out category, in a year when risk-taking proved nerve-wracking, was plain-vanilla fixed-income holdings: bonds, which yielded a 15.4 percent return.

The University’s financial report, with details on performance by asset class within the HMC portfolio, thus will make for extremely interesting reading. As of June 30, 2019—the end of the prior financial year—HMC’s assets were dominated by public equity (stocks: 26 percent); private equity (20 percent); and hedge funds (33 percent). It is reasonable to assume that domestic stocks performed relatively well; diverse international equities may have had more variable returns.

Private-equity valuations may be widely dispersed. Certain technology and biomedical enterprises have been leading the market, and private venture investments in those sectors may be performing very well, particularly versus investments in other industries. Economic conditions in general are far from robust—but record-low interest rates enhance the valuations of private-equity holdings.

Hedge funds—whose strategies and holdings are almost completely opaque—are perhaps the biggest swing factor, as they constituted $13 billion or more of Harvard’s endowment investments, presumably in a heterogeneous mix of strategies and assets. A significant portion of these holdings are expected, over time, to be redeployed into private equity—a multiyear process even in normal markets. For now, how well the hedge funds performed may be a major part of HMC’s fiscal 2020 results.

Other factors have a consequential impact on HMC’s performance, but in a different sense. During the past few years, HMC has made a concerted effort to reduce its real-estate portfolio, which had performed well but was considered fully valued and less attractive than other sectors; and its natural-resources holdings, which have continued to generate losses, despite prior sales and write-downs. In the current environment, those earlier decisions may have been especially productive. Certain real-estate assets have probably performed well for those who own them (warehouses, for e-commerce; some kinds of residential properties)—but hotels, retail space (like shopping malls), and central-city office towers have been punished during a protracted period of curtailed travel, social distancing, and remote work. Similarly, the pandemic recession choked off demand for energy, depressing prices, and for a while, at least, had similar effects on basic metals and related resources. Being less invested in these sectors probably helped this year.

The proof (or disproof) of these speculations about Harvard’s performance, and of the numerical estimates underpinning the endowment’s value provided above, will be forthcoming in the University’s financial report for this most unusual and challenging of years.

The Harvard, and Higher-Education, Financial Outlook

The pandemic and rapidly changing investment conditions affected Harvard in important ways during the past several months, as administrators and deans struggled to get a handle on University finances amid severe drops in executive-education and degree-tuition revenues and higher health and remote-teaching costs. When they drew up budgets for the current academic year last winter, deans assumed the formula promulgated for moderate distribution increases through fiscal 2021 would hold—a reassuring anchor as other sources of income plummeted. That was an important assumption: endowment distributions are fully half of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ revenue. But given the ensuing coronavirus, recession, and upheaval in financial markets, deans were then advised that the funds to be distributed would decrease 2 percent—a swing, versus budgeted expectations, of negative 4.5 percentage points in that revenue source. In yet another twist, they have seen that administration guidance on their endowment distribution change again in recent weeks: in August, they learned that the Corporation had approved a level distribution instead, reflecting improved financial-market conditions. Compared to the late-spring guidance for a reduced distribution, this effectively represents an increase in the funds to be distributed during the current year of perhaps $40 million to $50 million across the schools and faculties: less than originally expected last winter, when budgets were drawn up, but better than at the depths of the markets’ declines at the end of the spring term. It’s been that kind of year.

[Corrected October 2, 4:00 p.m.: The first sentence in this paragraph originally reported that the additional funds from the central administration derived from an additional distribution from the endowment; that is incorrect. Although the endowment performed better than expected last spring, the endowment distribution was not changed, and the distribution of $20 million in additional unrestricted funds to schools, affiliates, and programs, represents a reallocation of central administration funds, which it is now redirecting to those recipients.] The additional $20 million to be distributed from the central administration, announced this morning (the equivalent of 1 percent of the roughly $2.0 billion distributed from the endowment, understood to be unrestricted funds sent to endowment-owning schools, museums, and so on), will help. But it of course still falls short (perhaps a long way short) of covering incremental costs borne by the schools—and in no way compensates for the larger losses of revenue they face.

Now that the academic year has begun, Harvard is taking stock of pandemic-related costs (including testing, tracing, quarantining, building and operations modifications, and more), estimated at some tens of millions of dollars. In addition, tuition revenue will be reduced, as the College and many professional schools are far from fully enrolled—and room and board fees, for schools that offer housing and meals, are also sharply reduced. Executive education, events, and facility rentals are all depressed. And although much research has resumed, laboratories are not operating fully, so the rate of indirect-cost recovery (for overhead associated with research, such as buildings) is also less than robust. In a conversation with The Harvard Gazette last week, Thomas J. Hollister, vice president and chief financial officer, indicated that:

[R]evenues for this past year were down substantially from FY19. That is only the second decline of Harvard’s revenues since World War II. The other time was during the Great Recession of ’08 and ’09. And the staggering part about the losses of revenue—including due to room and board rebates, cancellation of continuing- and executive-education programs, sharp drops in rental income, health-related services, parking fees, and so on—was that it all occurred in a little over three months in the spring.

With respect to FY21, our most recent forecasts indicate that revenues will likely be down a second year in a row. We haven’t seen that since the 1930s. The key point… is the uncertainty. We face extraordinary, in some ways unprecedented, challenges related to the pandemic and ones that extend beyond it, including the economy, politics, societal inequities, and pressures in higher education. Each of these forces could have an effect, in varying degrees, on the University’s financial outlook for the year.

As noted, Harvard has decided to level-fund endowment distributions during this academic year. It has also frozen most hiring, faculty searches, and other variable costs; pushed back discretionary construction projects; frozen compensation not covered by union contracts (and upper-level administrators have taken pay cuts); and implemented a retirement-incentive plan for longer-service employees, with a large incentive (a full year of salary). According to the message today from Bacow and other Harvard leaders, nearly 700 eligible staff members decided to participate; they will depart by next June 30 at the latest.

Some peer institutions, with which Harvard competes for faculty and students, have charted different paths, presumably reflecting their own distinct revenue streams, cost structures, and assessment of risk. Stanford’s budget for this fiscal year incorporates a 3 percent increase in the distribution from endowment funds supporting financial aid, so that undergraduate aid and support for doctoral students could expand a total of 9 percent. The distribution from other endowment funds will be reduced 10 percent. And a $150-million withdrawal from unrestricted endowment funds was authorized, to cope with the exigencies of the pandemic. In the aggregate, endowment funding (which provides 20 percent of revenue), will rise somewhat. The university has also laid off more than 200 employees, furloughed others, and eliminated several hundred vacant positions.

Princeton, whose endowment funds about 60 percent of operations, indicated a willingness to let its distribution rate rise to about 6 percent, from the customary, long-term 5 percent goal. The university is in the quiet phase of a very large capital campaign.

Yale, which estimated pandemic-related revenue losses and increased expenses totaling $250 million, as of late September, nonetheless reported a $125-million operating surplus for fiscal year 2020. Although university leaders expect greater financial impacts during the current year than in the prior one, Yale has determined, in light of its surplus and cost disciplines, to “partially” lift a faculty-hiring freeze: it will approve “at least 60 new and continuing faculty searches” this year. It will also grant a 1.5 percent salary adjustment to all faculty and managerial/professional staff members earning less than $85,000 per year, effective October 1; and continue several large, high-profile construction projects. Even so, the community was warned that “it is still not business as usual, and we must remain prudent.” Yale, too, is in the quiet phase of a large capital campaign.

What lies in store for Harvard? Look for a full report at harvardmagazine.com as soon as the annual financial report is released. And then, as the holidays approach, look for the even more consequential announcements on what academic operations can proceed in the spring term, after the unusually long recess from campus beginning November 22 and extending to late January.