In the photograph here, taken on an overcast morning in the fall of 1956, you see the smartest Harvard Law School students in a student body of approximately 1,500. Each of these 58 students has been officially recognized by the Law School’s academic grading system as one of the most brilliant members of the entire class, and therefore they will serve as editors of the Harvard Law Review for the academic year.

This is the highest honor the school can bestow, and it carries way beyond the school itself. Upon graduation, while hundreds of others in their class compete for jobs, these 58 editors will be interviewed and courted by the most prestigious law firms in the country. Some will become associates in the most successful firms on Wall Street; others will become clerks to a United States Supreme Court Justice; others will become speech writers and campaign strategists for presidential candidates. These are the designated winners, groomed for ultimate and lasting success. I am one of the students in this picture. That’s me, next to the last row, third from the left.

In the fall of 1955, more than 500 men and six women had been admitted to the first-year class at Harvard Law School. As one of those women, I quickly found out that we were admitted but not exactly welcomed.

To begin with, we had no place to live. While the male students settled into their dormitory rooms, we were advised to explore the various apartments and boarding houses in the area around Harvard Square. I made friends with another first-year student, Julie, and we each took a room in a big old boarding house on Garden Street within walking distance of the school.

Early in the school year, Dean Erwin Griswold, as a special welcome for the handful of women in the class, invited us to his home for dinner. That evening we learned that the dean had fought for years to allow women into the Law School despite objections from other faculty members that we would be there only to catch a Harvard lawyer for a husband. And whether that was our goal or not, the fact remained that each seat one of us occupied in the classroom was a seat that would otherwise be occupied by a young man determined to make the most of his professional career as a Harvard lawyer. Could a woman make that commitment? The dean just looked at us and let that question hang in the air.

After dinner, over demitasse served by Mrs. Griswold, the dean moved on to more general observations. We learned that the stringent standards of the Law School required that for the next three years we concentrate every ounce of available energy and attention on the goal of learning how to think as a Harvard lawyer. To that end, we should understand that there were no glee clubs in the law school. No time for that. The law school’s academic standards were the highest in the nation and we would be competing with each of our classmates, 500 ambitious young men, more than half of whom were members of Phi Beta Kappa or valedictorians of their college graduation class. Or both. And with those remarks the dean welcomed each of us to the Law School class of 1958.

Neither the dean nor his wife mentioned that all the bathrooms in the halls of the law-school buildings were there for Harvard men only. Ever resourceful, however, we made our way to the basement of Austin Hall, where we found, and used, a janitor’s bathroom.

Another feature of first year that we did not hear about that evening at the dean’s home, but certainly learned about a few months later, was “Ladies Day”—when each professor would call on a female student to recite and analyze the most embarrassing case he could find. Thus in torts class I was called on to recite an ancient common-law case in which a plaintiff sought damages for the collision that occurred when a farmer’s “ass” ran out onto a public thoroughfare. The court ruled the farmer liable for damages caused by his “ass on the road.” After I recited the facts of the case and the court’s ruling, the professor asked what I would advise the farmer if I were his attorney. “In the future, keep your ass off the road.” “Yes. Thank you, Miss Boxley.”

Later that morning in the contracts class, I was quizzed by the professor on a theoretical case in which a young man sues for the return of his engagement ring once the engagement is broken. Does the young woman get to keep the ring? Does it matter how long the engagement lasted? Does it matter if he is the one breaking off the engagement? And what if she is breaking the engagement, but only because her church cannot sanction the impending marriage based on religious grounds? And in that case, suppose the young man’s mother is so distressed about the broken engagement that she has a miscarriage? Who pays for her pain and suffering? My dialogue with the professor went on—each of us with a straight face—for the entire class hour. Fun and games at law school.

Some 30 years later, at a class reunion, one of my classmates came over with a big smile to let me know that the “ass on the road” episode was his fondest memory of his entire time at law school. I have often wondered why it was acceptable—indeed wonderfully funny—to spend a day putting women students on the spot, but not acceptable to spend a similar day focusing on the two or three black students in the class. Why weren’t they both in bad taste? None of our classes covered this question.

During the academic year each first-year student took several written “practice exams,” participated in two “mock” appeals arguments, and engaged in fairly vigorous classroom dialogues conducted by the faculty. But a series of hours-long written exams at the end of the school year were the only tests that mattered. To ensure the security of those tests, each student signed those final exams not with his or her name, but with a number. Once the final scores had been determined, each of those numbers was attached to the matching name and your rating in the class was thereby fixed. No mercy here.

As spring approached and tensions rose, rumors began to circulate about the significance of those final exams. Of course, if your father was a senior partner of a law firm or headed up a private investment firm, your grades were not really all that important. But if you had no such connections, you had better study hard and aim for the top. And if you were a woman with no connections—at a time when many law firms would not even interview a woman candidate because they simply did not hire women—you had better study hard and not only aim for, but actually be at, the top. And I was clearly one of those women: my parents’ retail clothing store in Richmond, Virginia, did not count as a connection.

So what did it mean to be at the top? That was another topic of much speculation. We learned, by rumor and hearsay, that students at the top of their first-year class became editors of the Harvard Law Review. We didn’t know what these editors did exactly, but we understood that these were the designated winners, groomed for ultimate and lasting success. I absorbed all of this and it was clear that I had to become an editor.

The final exams were predictably gruesome: three hours of written responses in blue books to one after another series of legal issues which had never been precisely covered either in the case law we studied or in the classroom discussions. The challenge was to apply the underlying principles of all that material to these new problems. And your future depended on getting it right. My secret weapon was a York peppermint patty: as I read an exam question and began thinking through the issues, I would bite into that bright flavor of peppermint and chocolate, chew thoughtfully, and begin to write.

When the exams were finished, we all left Cambridge not knowing where anybody stood.

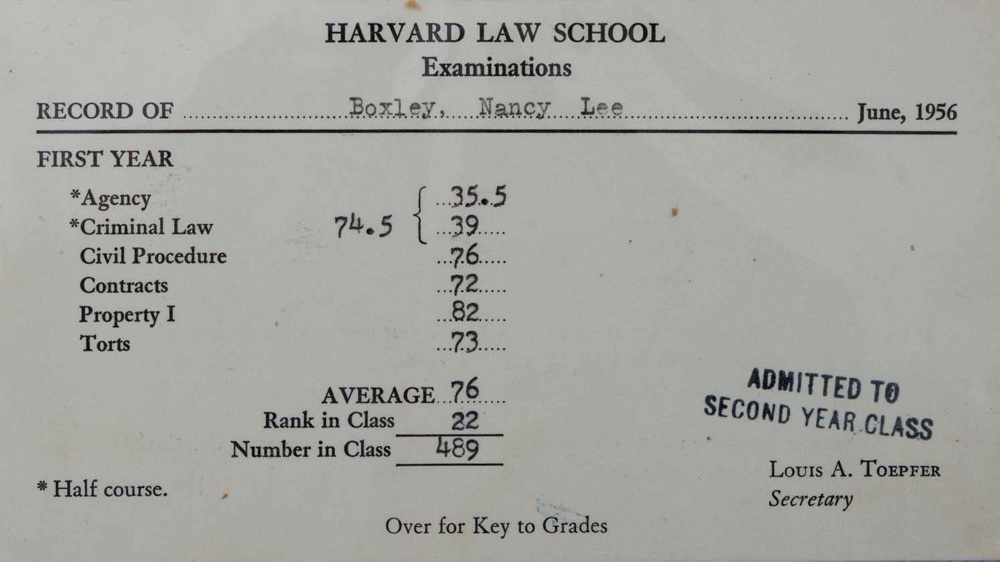

As a first-year student, your final grade score and your rank in the class was the law school’s final and irrevocable judgment of you, your worth, and your future. The results were mailed to each student in July. I was spending that hot, sticky summer with my family and trying to “relax” while waiting for the results. Finally I received this card [below] in the mail.

The mundane announcement of a magic number signaling admission to the Law Review

You will note that my rank in the class was 22. When I saw that number I had to take a deep breath and try to remember whether the magic number for the Law Review was 20 or 25. I had never seen the number written down. Over the next few days I tried to “relax” and “enjoy the rest of the summer.” I tried so hard my throat hurt and I couldn’t speak above a hoarse whisper. Finally I called the law school and—after being transferred from one wrong department to another—found out that the magic number was 25. I would become a second-year student and an editor of the Harvard Law Review.

So: mission accomplished! But what exactly was I getting myself into? To begin with, I had to return to Cambridge several weeks early to begin work on the Review. I quickly found out that the pressure to write and publish the best law review journal in the world eight times in nine months was intense and constant. Each issue contained articles written by law professors or other legal authorities after intense analysis, review, and possible revision by the editors. The editors also researched, analyzed, and published reviews and analysis of significant federal and state court decisions. The Review’s annual analysis of current Supreme Court decisions was nationally recognized as authoritative.

I worried that with the sheer volume of time spent on Review work, in addition to the full schedule of second-year classes and class assignments, my classroom grades would plummet and I would disgrace myself in the second year. Each editor was expected to—and did—spend at least 40 hours a week working on Review projects, either in the offices in Gannett House or in the law-school library. To compensate for this double load, each editor was granted access to the key to the library. Other students had to leave when the library closed at 10 p.m., but the editors could work through the night. That was a real honor.

Monday through Saturday, classes in the morning, work on the Review the rest of the day and into the night. Sunday day and night could be devoted to Review projects.

Actually, the routine was simple: Monday through Saturday, classes in the morning, work on the Review the rest of the day and into the night. No classes on Sunday, so the entire day and night could be devoted to Review projects.

As the only woman on the Review that year I did not experience any discrimination. I was expected to, and did, work as hard and as long as the rest of the editors. The goal was always excellence: meticulous, exhaustive excellence. No energy left over for chauvinist nonsense.

If you had an assignment to edit an article submitted by a professor or other legal authority, you would analyze each judicial ruling cited in the article and then analyze every subsequent case citing each of those rulings. Did a subsequent case question the validity of the original citation? Was the original ruling expanded in subsequent cases? Was it overruled? Were there additional cases related to the issues raised by the article which should be included? Once the original article was revised to incorporate these findings, it would be returned to the author for any additional comments or revisions, which would then be subject to the same research procedures as the original article. This final version would then be subject to extensive analysis by another Review editor sitting by your side and patiently, painstakingly, questioning the accuracy and thoroughness of every aspect of the article. This was done with respect: both of you were striving for excellence.

My experience as a law-school student evolved from a kind of controlled terror of failure throughout my first year to an emerging self-confidence. What I began to understand was that researching and writing legal articles honed your skills so that mastering classroom material became easier and faster. The Law Review reinforced that attitude with the unspoken premise that each editor had the intelligence and energy to do an excellent job—and was expected to do just that.

As spring approached that second year, the whole class seemed to relax; the days just seemed to offer more time, and interesting time at that. Recruiting scouts from several Wall Street firms arrived on campus to interview second-year students for possible summer internship positions. And—what a wonderful surprise!—some of them invited me to interview. So much for the rumor that these firms would not hire a woman lawyer. At least they were willing to interview a woman for a limited summer job.

I was plenty willing, too. I thoroughly enjoyed those interviews: in general the recruiters seemed to be impressed with me and I was certainly eager to see what it would be like to spend the summer as a New York lawyer. I flew to New York for additional interviews with the senior partners of some of those firms. A few weeks before classes ended that spring I accepted the offer of Simpson Thacher & Bartlett to work there as one of their three or four summer clerks.

The managing partner of Simpson Thacher had reserved a room for me at the Barbizon Hotel for Women in midtown Manhattan. That is where proper young women stayed: men were not allowed past the lobby. The hours were easy compared with work on the Law Review. That summer I worked with Whitney North Seymour, a senior partner and then-president of the American Bar Association, whose office provided a panoramic view of the New York Harbor and, smack in the middle, the gleaming Statue of Liberty. He was preparing an article for The New York Times Magazine on the refusal of some pharmacists to sell birth-control pills. Unlike a Law Review article that would have involved an exhaustive study of the historical, legal, and constitutional issues involved, this one made reference to those considerations, but also explored the economic, political, and sociological impact of this practice. I thoroughly enjoyed this expanded analysis. (Mr. Seymour was named as author of the article, of course, but a footnote referred to me by name as having contributed to its preparation.)

I also did my share of grunt work. Four days in a row I drove with a senior associate to a large electric-utility company in New Jersey where we conferred with the officers and directors to verify the accuracy of a detailed prospectus to be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Based on these meetings, I helped draft the prospectus, then returned to New Jersey for final approval of the document, which was finally filed with the SEC.

On the Friday evening of my last week at Simpson Thacher, the firm hosted a farewell dinner at the Harvard Club for us summer clerks. I was advised to use the club’s separate entrance for ladies, and did so. I smiled, of course, with the others at the dinner table when one of the senior partners toasted the special grace which the summer clerks had brought to the firm that year. I was relaxed and comfortable: earlier that afternoon that same partner had invited me into his office to let me know that the firm would be pleased to welcome me back on a permanent basis once I graduated. No talk of starting date or salary. Just a handshake. It was all I had hoped for.

The Board of Editors for HLR volume 71 (1957-1958). Ruth Bader Ginsburg (fourth row, far right) has joined the author (fourth row at left).

Returning to Cambridge that fall, our staff of Law Review editors was joined by the 25 new second-year students who had topped their first-year class, as well as 10 of our classmates whose second-year grades qualified them to serve as editors for their final year. We all posed for the annual Law Review photograph on the steps of Austin Hall (above). That’s me on the left, in the next to top row. The attractive young woman on the right is one of the new editors from the second-year class, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The photographer, in arranging our positions, commented that it was nice to see “two roses amid the thorns.”

Ruth and I, of course, each spent long hours working in Gannett House and in the library. At the same time, Ruth was also committed to her family, which included Marty Ginsburg, her husband, and her baby daughter, Jane. She didn’t have much spare time and I didn’t get to know her very well. Marty, on the other hand, was in my class, comfortably near the top but not on Law Review. It was easy to become casual friends with him and enjoy his stories about student life with Ruth and the baby, and his technique of putting his daughter to sleep by reading to her from the Internal Revenue Code.

I had become confident in my ability to analyze case law. The subjects we had studied the first two years—from contracts to criminal law—were essentially based on judicial decisions. The goal was to extrapolate the general legal principle from the particular facts of each case. This third year, however, was primarily focused on federal statutory law: the Securities and Exchange Act, the Internal Revenue Code, the laws of bankruptcy and antitrust law. In one of the Law Review articles I worked on, the interpretation of an Internal Revenue Code provision required not only a review of all pertinent case law and IRS regulations but also of a transcript of the congressional committee hearings prior to the law’s enactment.

I kept in touch with Simpson Thacher throughout the school year, having lunch with the office manager when he arrived in Cambridge to interview second-year students as potential summer clerks.

When classes ended that spring, I packed up and took the train to New York City for the last stretch of this whole adventure: passing the state bar exam and then practicing law as an associate.

Some 30 years after graduation, I attended a class reunion at the law school and was able to sit in on a first-year class on contracts. The professor, who used a microphone to speak in a normal voice, was an attractive young woman who was pregnant, wearing boots and a dress that came down to her knees.

Using the traditional Socratic method, she put a question to one of the students in the class. The microphone was passed from student to student and finally handed to the young man in question. He responded that he had some trouble with that case and at this time could not answer her question. Hands went up and the professor directed the microphone to another student, who gave a detailed answer which led to an extensive dialogue with the professor. All very calm and respectful.

How relaxed the whole classroom was! How gracious the professor was to simply move on when the first student could not respond successfully to her question. What a contrast to the tense and loud classroom dialogues of the 1950s, when both the professors and the responding students had to raise their voices loud enough to be heard by the hundred or so other students in the classroom. And when a student’s failure to successfully respond to a professor’s question would lead to a long, humiliating silence before another student in the class was called on to “help” the original student understand what an appropriate answer sounded like.

“We found that students learn better when they are not scared witless all the time.”

That evening I commented on this contrast to the dean, who said in effect: “We found that students learn better when they are not scared witless all the time.”