In his memoir of the 2008 financial crisis, former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner wrote that such crises are like “earthquakes”—they “cannot be reliably predicted, so they cannot be reliably prevented.” Former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke ’75 seemed to share that view when he said in a May 2016 talk that the Great Recession was triggered by “a twenty-first-century electronic panic by institutions…an old-fashioned run [on the banks] in new clothes.” And former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson, M.B.A. ’70, said in a 2018 symposium at the Brookings Institution that such crises are “unpredictable in terms of cause, timing, or the severity when they hit.” But what if all these policymakers are wrong?

That’s the contention of researchers at Harvard Business School, who find, in two separate sectors of the economy, that the combination of rapid credit growth and asset-price gains during the prior three years is associated with a 40 percent probability of entering a financial crisis within the next three years. “That’s an enormous number,” notes Gund professor of finance and banking Robin Greenwood. And that risk compares to just a 7 percent probability in normal times. The association just “jumps out at you. You don’t have to do any fancy analysis to uncover it,” adds Greenwood, who is coauthor of the Harvard Business School (HBS) working paper, “Predictable Financial Crises,” with professor of business administration Samuel Hanson, Loeb professor of economics Andrei Shleifer (currently also a visiting professor at HBS), and Jakob Sørensen, a former visiting fellow from the Copenhagen Business School. “The predictability we document,” they write, “favors macro-financial policies that ‘lean against the wind’ of credit market booms.”

Prior work, notably including a study by Safra professor of economics Jeremy Stein, has shown that expansion of credit often predicts future contractions of gross domestic product (GDP), a measure of national economic output. But using measures of credit growth alone provides only modest forecasting ability, Greenwood says. “You miss an enormous number of crises, and predict crises that never materialized.”

In the new study, encompassing 42 countries between 1950 and 2016, Greenwood and his coauthors show that within the business sector, the risk of a crisis increases when credit growth during the prior three years is in the top fifth of the historical range, and stock market valuations are simultaneously in the top third. In the household sector, increased borrowing and elevated home prices are the relevant metrics. Each of these pairings “independently predict[s] the arrival of future crises”—with the probability of a crisis rising to at least 13 percent during the year after those benchmarks are reached, and as high as 45 percent within three years. These data, the authors contend, show that such crises are “slow to develop, suggesting that policymakers have time to act based on early warning signs.”

In the rare historical instances when indicators in both sectors flash red, the probability of a crisis occurring within the next three years rises to more than 68 percent, and the outcomes are particularly severe, as has been seen in Japan (1988-1989), Spain (2005-2007), and Iceland (2005-2007). And there are global spillovers among economies, Greenwood points out. When risk is high generally, based on indicators within specific countries, even countries whose own economies aren’t overheated have an elevated probability of a crisis (where the banking sector becomes “severely impaired, as evidenced by widespread bank failures or severe withdrawals”).

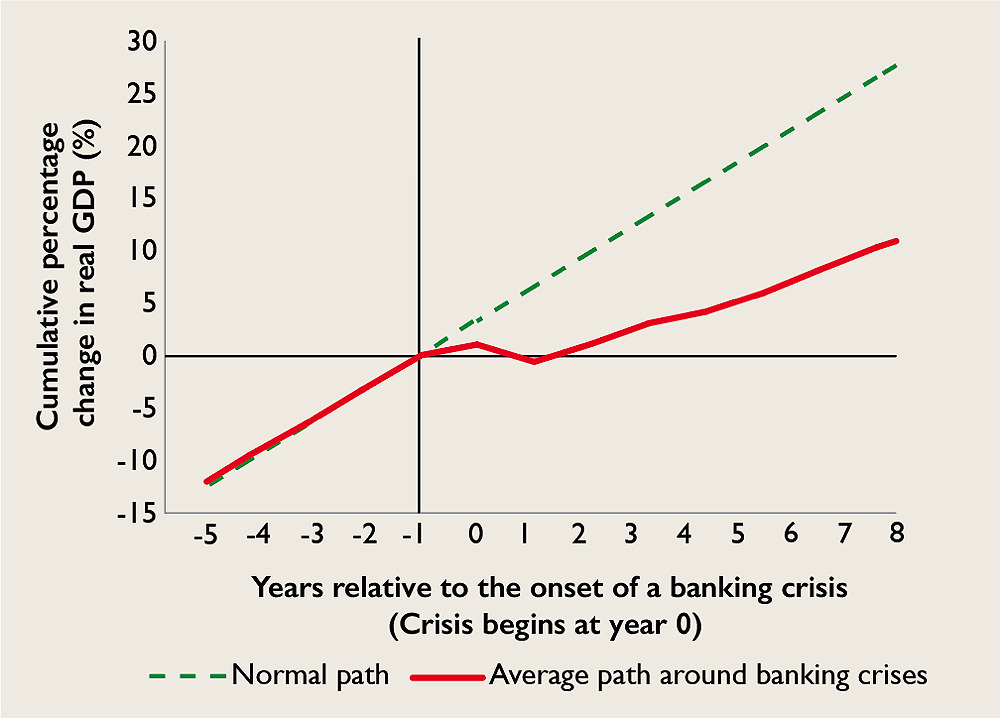

A diagram showing the effect of banking crises on the average growth of real GDP in 42 countries from 1950 to 2016. The dashed green line shows the normal path of GDP growth; the solid red line shows the lasting effects of a crisis. The year prior to crisis onset is year “-1” and the year of onset is year “0.”

Source: Greenwood, Hanson, Sorenson, Shleifer (2020)

There are powerful incentives for acting to prevent such economic disasters in the first place—“taking away the punch bowl,” as the authors put it, channeling the late Fed chair William McChesney Martin, “when the party starts to get out of hand”—because of what happens to a nation’s GDP in the aftermath of a crisis. National output declines—and “never recovers the gap” to the trajectory of economic growth it was on before the crisis struck, Greenwood explains. These events can be “incredibly costly for an economy and for the world” because the damage to future economic growth is lasting (see chart above).

Therefore, the authors write, “when a policymaker faces a greater than 40 percent probability of a financial crisis over the near-term, and a comparable probability of a recession, a wait-and-see attitude appears ill-advised.” Steps toward prevention or alleviation in the business sector might include increasing capital requirements for banks that make commercial loans. In the housing sector, increased down-payment requirements on mortgages, by mandating stricter loan-to-value ratios, would have a cooling effect. Indirect corrective actions, says Greenwood, might include “tightening monetary policy to lower the probability or severity of a financial crisis.” But because all such actions have costs, he points out, they must be weighed against the probability and potential impact of a crisis. The trick, he says, is to take small preemptive actions before a crisis can develop. “Taking away the punchbowl when everybody’s already drunk and angry,” he warns, “actually exacerbates the problem.”