As recently as 10 years ago, Jeannie Suk Gersen was still telling people that the area of law she specialized in—sexual assault and domestic violence—didn’t hold much interest for the general public. A quiet corner of the profession, she thought. Remembering that now, she laughs. “But, you know,” she adds, “every area of law does end up moving into focus. Because, in the end, law is really about every aspect of our lives.”

Which is partly why Gersen, J.D. ’02, has always taken it so seriously. “Words don’t just describe things,” she explains. In the law, “words actually do things.” So it’s important to get those words right, to reach as close as one can to the truth.

And that is what the Law School’s Watson professor of law tries to do, as a legal scholar and a public intellectual with kaleidoscopic interests. She has written about consent and intimacy with “sex robots,” fashion design’s place in copyright law (see “Real Fashion Police,” July-August 2010, page 9), and the legal protections of racially offensive trademarks. In a 2019 TED Talk, she described the “tacit rules of marriage” that divorce makes painfully explicit—sacrifice should be a fair exchange, child care is never free, some belongings should stay separate—and how couples can discuss those rules while the conjugal bond is still strong. (She spoke from experience, she noted in the talk: her first marriage, to Frankfurter professor of law Noah Feldman, ended in divorce; she is now married to Austin professor of law Jacob Gersen.) In 2017, she taught a course on law and the performing arts with ballet star and Juilliard president Damian Woetzel, M.P.A. ’07.

Her most consistent subjects, though, are the ones that now rivet public attention: gender, sexual assault, sexual harassment. Since 2014, Gersen has contributed to The New Yorker, where she writes wry, trenchant columns on the challenges to the U.S. legal system embedded in tectonic shifts like the #MeToo movement and the debate over Title IX and campus sexual assault. In September 2018, she sat in on the explosively contentious hearings for Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination, filing dispatches about the legal conundrums they raised: witness testimony, evidentiary norms, procedural protections for accuser and accused.

Elsewhere, she scrutinized the precarity of transgender students’ rights and the fight over gender-neutral bathrooms. In 2019, she wrote about several state legislatures’ plans to end the “gay panic” defense (the claim that a violent act was a sudden emotional reaction to an unwanted advance from someone of the same sex) and how those efforts might have unintended consequences for women who kill abusive men or racial minorities who claim to have feared the white victims they killed. “The gay-panic debate,” she wrote, “goes beyond excuses for murder. It reminds us more basically that biases can frame—and flip—perceptions of guilt.”

Reshaping the Conversation

Throughout, she has stuck to a position as measured as it is embattled: the desire to see an end to the impunity long attached to sexual assault, but also a devotion to the principles of due process and procedural fairness, grounded in a wariness about the unintended consequences of well-meaning action. Gersen is a feminist herself; an early and formative influence was legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon, the Ames visiting professor of law at the Law School, whose work helped create the legal claim of sexual harassment. MacKinnon interpreted sexism not as a series of individual incidents but as a structural and institutional attribute of human society, and that idea profoundly shaped Gersen’s own thinking. She believes the #MeToo movement’s push toward a reckoning is needed and overdue, but also sees its path as full of pitfalls and temptations. “I don’t think we can achieve justice and equality, including for women,” she stresses, “by undermining fair processes and our constitutional values.”

“I don’t think we can achieve justice and equality, including for women,” Gersen stresses, “by undermining fair processes and our constitutional values.”

That critique has put her at odds with other feminists and scholars who’ve come to see due process as a barrier to rooting out and punishing sexual misconduct. This kind of conflict is not unfamiliar to Gersen. Her 2009 book, At Home in the Law, explored how contemporary domestic violence law, despite its attempts to empower women and free them from abusive marriages, can instead dismantle the boundaries between public and private spaces, allowing the state to dictate family life in ways that overrun autonomy, for women as well as men. After the book appeared, she was accused of being dangerous and irresponsible; at one academic conference someone called her “Hitler.”

“Jeannie is intellectually fearless,” says Bemis professor of international law Jonathan Zittrain. That’s a common sentiment among her colleagues. “She is willing to follow an idea wherever it might lead.” And usually, he adds, to good effect. “She has a piercing way of analyzing things in a new light, because she identifies unstated assumptions in a discourse that participants across a spectrum might have missed. Once they’re in plain view, they can reshape the conversation.”

That analytical style—a contrarianism she neither seeks nor shrinks from—has brought her into tension with Harvard, too, mostly over its approach to sexual assault on campus. This is partly what her faculty peers are talking about when they describe her as “brave” and “independent.” (“There are a lot of people who are afraid to say things in our business,” says Learned Hand professor of law Jack Goldsmith, “and she’s not afraid to say what she thinks.”) The thorny complexities of Title IX regulations and of policing campus sexual assault are both a scholarly interest as well as a practical one: as a mediator and legal advocate, she has represented both complainants and respondents in sexual-assault disputes at the University. “Her whole response to Title IX has been very, very striking—and I think completely correct,” says Beneficial professor of law Charles Fried, who was Gersen’s teacher before he was her colleague. “But hers is not the common view in communities like this.”

In 2016, Gersen and her husband co-published a widely cited article in the California Law Review describing the “sex bureaucracy” of administrative oversight on campuses that has expanded to regulate not only sexual violence and harassment, but sex itself. Among other critiques, they noted the “watered-down notions of nonconsent” in university policies that “can allow ambivalent, undesirable, unpleasant, unsober, or regretted sexual encounters to meet the standard.” Under these circumstances, Gersen worries, sexual misconduct policies end up being selectively enforced, and, inevitably, that selective enforcement falls disproportionately on marginalized racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups. As an attorney, she says, she has seen this happen.

Gersen first came into confict with Harvard over Title IX in 2014, when the University announced plans to change its sexual-misconduct policy in response to a “Dear Colleague” letter issued by the Obama administration, laying out guidelines for the 7,000-some colleges that receive federal funding. Among Harvard’s planned changes were an expanded definition of sexual wrongdoing and a lowered standard of proof: from “reasonable belief” to a “preponderance of the evidence,” the lowest possible threshold. Alarmed, Gersen and 27 Law School colleagues published an open letter in The Boston Globe, asking Harvard to reconsider. And after some lurching negotiation, that’s what happened. The University allowed the Law School to set its own policy for adjudicating sexual-misconduct disputes, and then later moderated its campus-wide policy to be more in line with the protections and procedures the law professors had requested. “And so, over the years,” she says, “I’ve been much less unhappy about Harvard’s treatment of these cases.”

But a new wrinkle appeared last August, when new Title IX requirements from the Trump administration’s Department of Education went into effect, reversing many of the Obama-era guidelines. In response, Gersen says, Harvard and other schools began seeking to redefine some instances of sexual misconduct as outside the reach of Title IX, in an effort to avoid the new rules. “I feel like Harvard is about to shoot itself in the foot again,” she said during an interview last October, adding that she didn’t expect the tactic to hold up in the long run; litigation began challenging it in the courts almost immediately, “and so far it’s not looking good for the universities.” (In late January, Harvard provost Alan Garber announced a working group to revisit the University’s new sexual-harassment policies, “to ensure they are as effective and inclusive as posible, while remaining compliant with federal law.”) The whole episode demonstrates, Gersen says, the wrenching difficulty in navigating a path toward fairness and justice in a realm of human life as complicated, personal, and “inherently ambivalent” as sex. “It’s such a tricky thing,” she often says. All the more reason, she believes, to hang onto bedrock principles of fairness.

“Not Like Other Asians!”

Gersen grew up in Queens, New York, the daughter of immigrants who had fled North Korea as children, and then moved to the United States from South Korea when she was six and her younger sister, now a law professor at Yale, was four (a third sister was born in New York). In her 2013 memoir, A Light Inside: An Odyssey of Art, Life, and Law, Gersen describes the loneliness and bewilderment of those early American years, as she struggled to learn English and acclimate to a new society, a shy, observant child who felt most at home with books and artistic expression. She learned to play the piano and paint and recite poetry. Her first serious passion was dance—she fell hard for Baryshnikov and Balanchine. In junior high school, she took classes at the School of American Ballet, until the training began to interfere with her regular school schedule, and her parents forbade her to continue—a heartbreak that still lingers decades later. Instead, she attended Juilliard’s pre-college program, studying piano, an instrument she had come to love through dance. Then: a literature degree from Yale; a Marshall scholarship at Oxford, where she earned a Ph.D. in four years; and, finally, law school. There, says her former teacher, Loeb University Professor emeritus Laurence Tribe, “I was always impressed by how both meticulous and yet unconventional her insights were. She would often come at issues in a kind of perpendicular way. Rather than finding a point between A and B, she would say that maybe that axis is the wrong axis.”

Gersen and her mother in Seoul in 1974

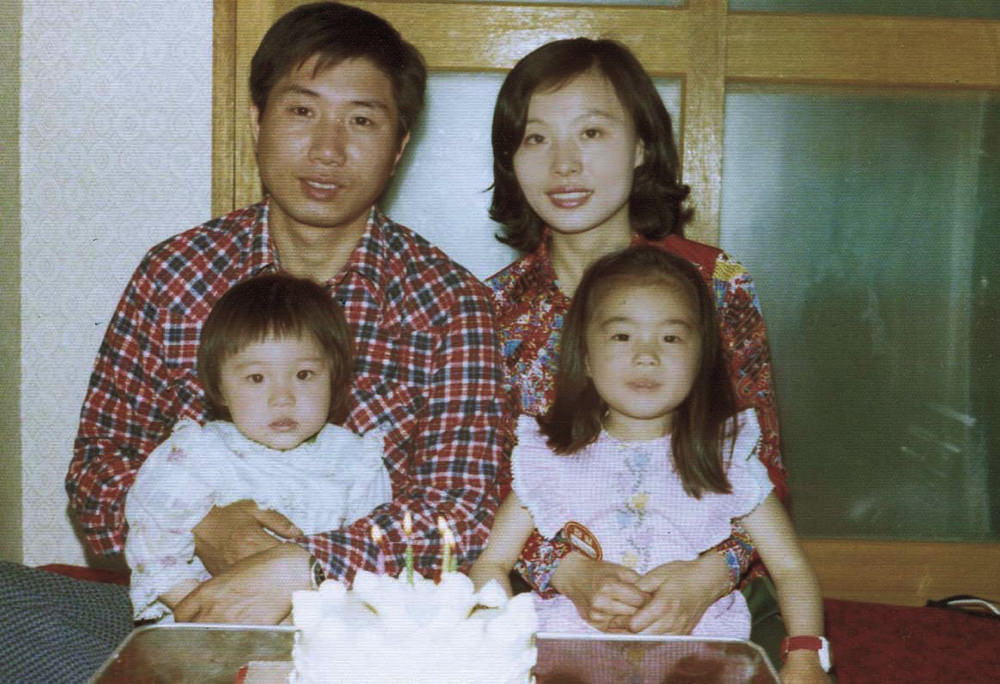

With both parents and her younger sister in 1977

Photograph courtesy of Jeannie Suk Gersen

During a high-school recital at Juilliard in 1990

After a Supreme Court clerkship with Justice David H. Souter ’61, J.D. ’66, LL.D. ’10, and a yearlong stint as a prosecutor in the Manhattan district attorney’s office, she returned to Harvard to teach. In 2010, she became the first Asian American woman to win tenure at the Law School, which made her a celebrity in South Korea.

“She has one of those amazing brains,” says Williams professor of law I. Glenn Cohen, who worked on the Harvard Law Review with Gersen. “She was a year ahead of me in law school, and we all regarded her more like a faculty member, even back then. She just seemed to know everything.”

During the last three years, she has covered the lawsuit brought against Harvard by Students for Fair Admissions, which charged that the University’s “holistic” admissions policies discriminated against Asian American applicants. (Thus far, Harvard has prevailed; for Gersen’s perspective, see this magazine’s podcast series, Ask a Harvard Professor.) Gersen guided her readers through the nuances of that case, its threats to affirmative action, its revelations about legacy enrollment, and what she called, in one column, “the many sins of college admissions.” She also drew on her own firsthand experience, as an Asian-born woman educated and employed in elite universities. In a 2017 dispatch, she recalled being a young college applicant striving for competitive academic placements and being told that she’d won one scholarship “because I had moving qualities of heart and originality that Asian applicants generally lacked.” In truth, she knew she wasn’t much different from her Asian peers: reticent, diligent, dutiful students whose accomplishments and activities mirrored hers. “But I got the message: to be allowed through a narrow door, an Asian should cultivate not just a sense of individuality but also ways to project ‘Not like other Asians!’”

Normalizing Trauma

Gersen’s current project is a book-in-progress on the concept of trauma and its growing influence on the American cultural and legal landscape. This is both a new and old topic for her: she has not written about it extensively before, but it is rooted in her previous work and some of her deepest family memories. “Right now,” she says, “we’re in a very trauma-focused time,” a trend she traces to the September 11 terrorist attacks. Before then, she notes, the word “trauma” rarely appeared in general-interest publications. Now, it’s everywhere: “Trauma is a concept that’s quite central to how everybody talks about what’s happening, both to the country and to themselves.” And there’s a lot to unpack, she says: its origins (psychiatry, politics, and legal theory all contributed) and “how it rose, and what it is doing to our law, to our society, and to us.”

At its most basic, the concept of trauma gives people a vocabulary for talking about harm and responsibility, she says. “And of course, the law is all about who has harmed whom and who is responsible for what.”

Perhaps the most straightforward of those questions is the first one. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) initially emerged as a way for psychiatrists to name the uncontrollable suffering of troubled Vietnam War veterans in their care: depression, anxiety, nightmares, flashbacks, and insomnia. In 1980, PTSD became an official diagnosis. The women’s movement picked up the concept and carried it into the realm of sexual violence, where it took even deeper root in the popular imagination. “Sex for women and war for men,” Gersen summed up in A Light Inside, “are the twin paths along which the idea of trauma has developed.”

At its most basic, the concept gives people a vocabulary for talking about harm and responsibility, she says. “And, of course, the law is all about who has harmed whom and who is responsible for what.” As emotional harm came to be increasingly recognized by the law, beginning in the early 1900s, “it started drawing upon psychiatric expertise, and then the changing ideas about how the mind works and about what kinds of things are harmful.…There is a lot of descriptive power in the concept of harm that trauma allowed people to grasp.”

But there is also an unavoidable—and familiar—tension. The original definition of trauma implies something extreme: a dramatic break from ordinary experience. But the events that many women conceived as traumatic—experiences like rape and domestic violence, and more recently, sexual harassment—were not so unusual. “That tension is kind of at the heart of how we think about trauma,” Gersen says. “More and more, we have seen almost a normalization of a traumatic way of existing and of thinking about existence.” The #MeToo movement accentuated this contradiction: “#MeToo is about the commonality of an extraordinary experience—or, rather, an experience that one may have described at one time as extraordinary, but then we realized that it’s not. It’s actually the most ordinary thing that women, especially, have experienced.”

What all this means for the law is complicated and unsettling. The concept of trauma has implications for due process and investigation, in both civil and criminal contexts. For instance, Gersen says, university trainings about sexual-harassment policies often focus on theories of harm. “And there are lots of ways that you can describe what the harm” is of discriminating or harassing. More and more often, she says, the concept of trauma is the framework that universities choose for how “we train people to think about the harm they may experience or inflict.” Teaching people to understand sexual discrimination as a traumatic ordeal, for instance, can alter how they feel about the experience, she says, “which could also affect how they then think about the processes that lead to establishing whether something did or didn’t happen.”

Similar questions arise in cases of alleged rape and sexual assault. “In recent years, there have been some parties who have argued that due process causes trauma to women who are victimized,” Gersen says. In the 1970s and 1980s, when rape-shield laws were developed, much argument centered on concerns about traumatizing rape victims by questioning them pointedly about their sexual history or sexual reputation, or asking questions like, “What were you wearing?” “That was where it began,” she says. “But now it has gotten to the point where just cross-examining the victim at all, even if you avoid those kinds of questions, might be seen by a number of people as in itself traumatic.”

Gersen views that belief as a real, if unintended, threat to basic legal fairness. “You have due process as a way of expressing that you don’t know whether someone is guilty or not,” she says. “And if you’re not open to that, then it’s not truly due process.” Part of the danger, she says, arises from Americans’ increasing polarization over what she calls “the rhetoric of believing.” “The idea that you ‘believe women’ or ‘believe the victim’ as part of the political imperative of righting injustice in society—I don’t think that a lot of lawyers would ever take that literally as a blanket matter. But as it becomes almost an aspirational rallying cry, it does have some gravitational pull on due process, and on the openness with which we explore and probe problems.” Trauma by itself is often assumed to be evidence of the veracity of an accusation.

Gersen began thinking about this book about 10 years ago, not long after At Home in the Law was published. “But then I realized later that…I’ve been, in some way, working on trauma for all my adult life.” While at Oxford, she wrote Postcolonial Paradoxes in French Caribbean Writing, about the literature of Martinique and Guadeloupe, which is steeped in ideas of trauma related to colonialism.

But questions of trauma were lodged even deeper in her emotional and intellectual awareness. The predicament of Caribbean francophone poets echoed her own family’s experience during Japan’s occupation of Korea. As a schoolgirl, her grandmother was so thoroughly drilled in Japanese that she spoke it almost better than Korean, Gersen says. After the Korean War began, her parents and grandparents all fled to South Korea: her mother’s family on a U.S. military ship from Wonsan, and her father’s family on foot from Pyongyang during a freezing winter. His baby sister died from exposure while being carried on his mother’s back, and the family had to move on without a burial. Earlier, a great-grandmother had disappeared without a trace during the chaos of a bombing; the family screamed and searched but couldn’t find her. Gersen’s earliest memories are suffused with her grandparents’ mourning and homesickness and loss. She writes of her grandfather stretched out on his bed, “waking sometimes to sob spectacularly, filling small rooms with unspeakable grief.”

Seoul, where Gersen’s parents grew up, “was our home, but it wasn’t our home,” she says. “For my family it was almost a literalization of trauma as an extreme break: the country was broken in two and they could no longer access their home.”

Seoul, where Gersen was born and where her parents finished growing up, “was our home, but it wasn’t our home,” she says. “For my family, it was almost a literalization of trauma as an extreme break from the rest of life: the country was broken in two and they could no longer access their home.” They never again saw the places and people they’d left behind. “My parents are in their seventies now,” Gersen says, “and they will likely die without ever being able to return.”

Later, at Yale, Gersen studied with Cathy Caruth (now at Cornell), who specializes in the literature and theory of trauma; she introduced Gersen not only to the psychological concept, but also to its effect on language and storytelling. After law school, Gersen settled on criminal law, partly, she thinks now, because of an attraction to those nas-cent ideas. “It probably reflected my interest in working with, or being close to, these concrete manifestations of traumatic experience”—violent crimes and their victims, people driven to commit crimes by traumatic backgrounds, even the ways in which “the criminal system itself is an extremely traumatic institution for the people that it touches.”

As a prosecutor, she worked on cases involving domestic violence, street violence, child abuse, and prostitution. Most were misdemeanors, the small-time charges that get handed to rookie prosecutors. “And I was really taken aback in my first months there,” she says, “by how deeply the language of trauma, the rhetoric of trauma, the concept of trauma, had shaped the way prosecutors were thinking about what they were doing,” even when the crimes were relatively undramatic.

Something was taking root in the law, Gersen realized. “It was amazing and interesting to see a concept that had been developed in one extreme context then become more normalized in the rest of the world.”

* * *

Last year, just days before the pandemic shut down the University, Gersen and a few other professors gathered at the Law School for an event titled “Why I Changed My Mind.” An auditorium full of people turned out to hear Harvard scholars wrestle with their past opinions. Laurence Tribe talked about the Second Amendment; Kemper professor of American history Jill Lepore spoke of Scopes trial prosecutor William Jennings Bryan.

But Gersen offered a more elemental reckoning, about the complex and sometimes slippery search for truth. Recalling her undergraduate experience as a rape counselor, she told the audience that in those days, the chief imperative was, “You always believe the victim.” It was fundamental to her training: “You don’t doubt that what they say happened is what happened.” As “a young person and a feminist working in the field of rape counseling,” she said, this principle was almost sacred. It was the reason why, as a law-school student a few years later, she told one professor that she could never be a defense attorney or a public defender: it would mean representing people accused of rape and sexual assault. Instead, “I wanted to prosecute people who were accused of committing violence against women.”

Over time, something shifted. Working in the Manhattan DA’s office, Gersen began to realize that she didn’t always believe the accuser. “I became more open to the idea that even as a prosecutor, my job…was to not start out believing anyone.” That may not sound radical, she acknowledged, “but for me, in my personal journey, it was. And I know from my experience as a teacher that lots of people enrolled in law school are going through similar things.”

Later, she spoke about the importance of finding a passion for moderation, and of the substantive moral commitments that have led her away from comfortable, mainstream conclusions about how justice works. She talked about sitting in a law-school class on September 11, 2001, and listening to angry, frightened classmates call for immediate bombings and the arrest of “people who are even remotely suspicious.” That memory proved an early push toward a later revelation. “There is something we would be papering over,” she added finally, “if we didn’t acknowledge that the whole idea of changing your mind—the reason it’s important—is because each person is on a search for the truth.” She paused for a moment, and revised. “Or, for something that is more true than what came before.”