When Richard Evans Schultes ’37, Ph.D. ’41 became director of the Botanical Museum of Harvard University in 1967, he could not have imagined that he would soon discover a collection of beautiful paintings hidden behind a shelf of books in the departmental library. These paintings illustrated all of the plants mentioned by Shakespeare, and they showed how extensive Shakespeare’s knowledge of botany was.

In the spring semester of 1968, I was a Harvard undergraduate English major looking for a biology course; during “shopping period” I sampled and decided to take Schultes’s course, “Plants and Human Affairs.” Schultes was an “ethnobotanist,” someone who studied how different cultures use plants. He was a fascinating teacher, and his course had its own dedicated classroom in the Botanical Museum, a room filled with Amazonian artifacts that he had collected. Each year he gave his class a demonstration of how to shoot an Amazonian blowgun that he kept in the classroom.

Schultes had traveled in the jungles of the northwest Amazon region, and lived with the indigenous peoples, for 14 years before he joined the Harvard faculty, collecting plants that were known only to the local tribes and trying to save that knowledge, before it vanished as the tribes adapted to modern cultures. He was particularly interested in plants with possible medicinal uses, such as arrow poisons that could be used as muscle relaxants for surgery. He described coming out of the jungle at the beginning of World War II to find a request from the U.S. government that he go back into the forest to search for rubber trees, since natural rubber was needed for military airplane tires and the war had cut access to rubber plantations in the South Pacific.

The course required a term paper, and I decided to combine it with my interest in Shakespeare by writing about plant-derived poisons mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays. It has always been an axiom at Harvard that if a student can justify an unusual idea, it will be approved, and Schultes welcomed the topic. After I completed it, he invited me to submit it for publication in the botanical journal he edited, Economic Botany. Thus, I had the opportunity to work with him for the next two years as I revised and polished it for publication. But there was also another reason why Schultes approved my topic.

He confided that he had recently found a spectacular collection of nineteenth-century paintings of Shakespeare’s plants hidden behind a row of books in the departmental library. He said that one of his predecessors, Oakes Ames (director of the Botanical Museum from 1923 to 1945) had found the paintings in a bookstall along the Seine during a trip to Paris, had bought the collection, donated it to the Museum, and then had apparently hidden and forgotten it behind the row of books.

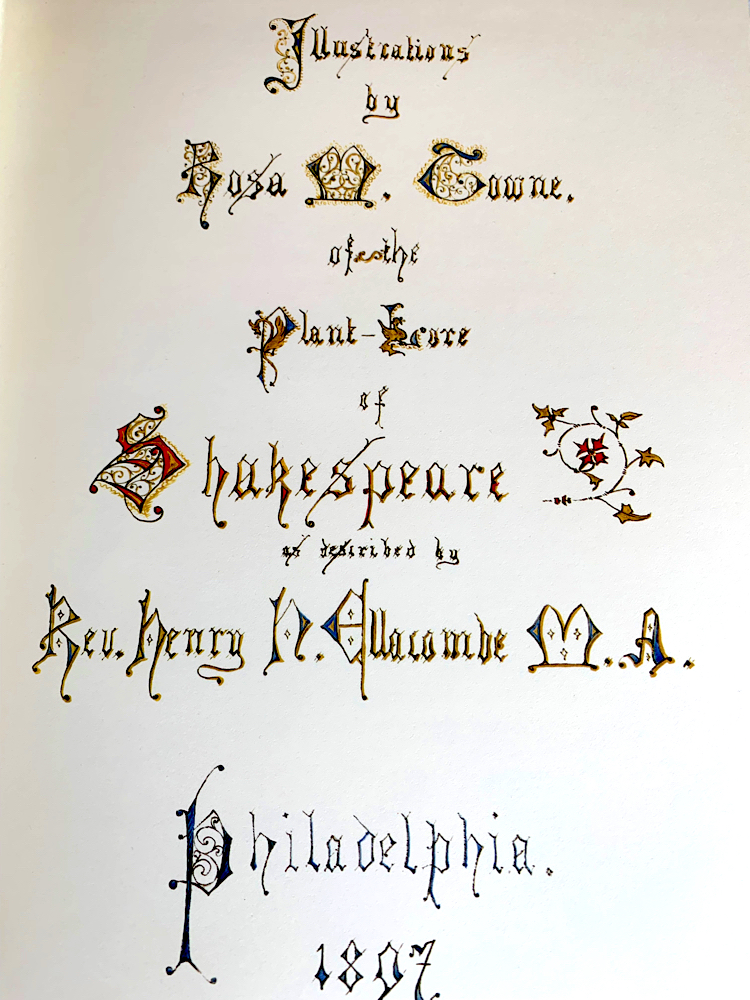

Illustrations by Rosa M. Towne of the Plant Lore of Shakespeare

Artwork by Rosa M. Towne and photograph by Edward Tabor

Rosa M. Towne (1827-1909) painted these illustrations between 1888 and 1898, including all plants Shakespeare mentions in his plays and long poems. In an introductory note to the collection, she wrote that she had decided to do the paintings using “live plants and trees” as models whenever possible. She accompanied each painting by a Shakespeare quotation in which it is mentioned.

The collection comprised 73 paintings of 182 plants, botanically accurate and mostly depicted either in flower or with berries or other fruits. When Shakespeare described several plants in one sentence, she painted these two or three plants in a single painting, artfully assembled but separate enough to appreciate the beauty of each. She also sometimes grouped plants from different plays, such as holly and mistletoe, in this case perhaps because they are both evergreen and associated with Christmas.

(1) Holly.

As You Like It, Act II, sc. 7.

(2) Mistletoe.

Titus Andronicus, Act II. sc. 3.

Artwork by Rosa M. Towne and photograph by Edward Tabor

Schultes was so impressed by the collection that he decided to look for a publisher to make high-quality reproductions that could be bound as a book. Over the next few years, Schultes updated me about his search for a suitable publisher, a search that took much longer than expected. He often met with publishers while travelling for business or pleasure, including trips to the United Kingdom where he had been most hopeful of finding a suitable publisher, but he could not find one who could meet the high standards of quality that he felt these paintings deserved.

Finally, he found an engraving company in Louisville, Kentucky, which in a test run was able to produce fine reproductions on thick, art-quality paper. Even after the publisher had been selected, production was painstaking and took several years. In 1974, a limited printing of 2,500 copies was published as Plant Lore of Shakespeare. Several hundred copies were provided to the Botanical Museum to sell in its gift shop, along with individual unbound pages to be sold as artwork. The proceeds from these sales formed a fund to buy books for the museum’s library.

Schultes invited me to the publication party for the book in 1974 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where Rosa Towne had once enrolled as an adult student. At the publication party I saw the published book for the first time. It was a large leather-bound folio edition, 15 inches long, a format that is unusual in modern times, even for art books. But a folio was particularly appropriate for a publication related to Shakespeare, since the so-called “First Folio” of his plays contained many works for which no other copies survived. Thus, just as Shakespeare’s folio preserved his plays, the folio of Towne’s paintings rescued them from obscurity, ensuring their availability for future generations.

(1) Mulberries. (2) Cherries.

Venus and Adonis

Artwork by Rosa M. Towne and photograph by Edward Tabor

The discovery of the Rosa Towne paintings by Oakes Ames, and their rediscovery and publication in book form by Schultes, were also important cultural rescues for the future of Shakespeare studies. The book shows the extent of Shakespeare’s botanical knowledge, provides a compendium of the 182 plants that we know Shakespeare was familiar with, and lists their common and scientific names. It provided, for the first time, a single collection of botanically accurate paintings that would help scholars and critics visualize exactly what Shakespeare had in mind when he mentioned a plant or when a plant played a key role in the action of one of his plays, such as the plant-derived poison used by Hamlet’s uncle to kill Hamlet’s father, the king.

I would have loved to own a copy of Plant Lore of Shakespeare, but at that time it was selling for $1,000 ($5,200 in 2021 dollars), and that was far beyond what I could afford. Several years later, I must have expressed this wish to Schultes, and he offered to make a copy available to me if I made a cash donation to the Museum. Before he shipped the book to me, I asked him to inscribe it. His inscription, dated September 16, 1981, read, “Shakespeare means many things to many people. The lover of plants finds him in many ways a worshipper of nature.”