Matthew Cappucci ’19 has never exactly fit in, and at a bingo hall 40 minutes east of Washington, D.C., it is no different. He is so much younger than his adversaries that a nearby grandmother feels compelled before each game to tell him which bingo sheet to use and how a “bingo” can be achieved. Cappucci thanks her for her generosity amid the competition. Players speak only in the moments between rounds and surround themselves with special bags for their ink daubers and auto-filling tablets. One woman has assembled a shrine for good luck. What few people in the room know is that Cappucci—the exuberant 24-year-old sitting toward the hall’s back left—is the fastest rising star in the world of meteorology. When they get home, they might see him on the local Fox station, where he’s featured on-air talent. They can see his coverage of local and national weather in The Washington Post and hear his cheery voice on WAMU, the local NPR station, where he’s a member of the Post-affiliated Capital Weather Gang. During hurricane and tornado seasons, he travels around the country in an armored truck and reports live for networks across the world.

In about 15 minutes, Cappucci—now intently daubing his bingo card—is set to receive a call from the BBC in which he will describe the development, trajectory, and possible impacts of Hurricane Sam, a major storm brewing over the Atlantic Ocean. But its status is so familiar to him, etched into his mind through a lifetime practice of daily analysis of radars, models, and data, that he needs almost no time to prepare for any one radio appearance. At one point, he considers whether he could complete his interview during a bingo game.

The call comes minutes after the bingo ends, right as he merges onto the highway. He pulls onto the shoulder, grabs the colorful notes blotted with his dauber during a game, and snaps to a level of enthusiasm and resolve that gives the cabin of his Honda Ridgeline the kinetic intensity of a full-blown TV studio.

“Right now, Sam is a beastly storm—has winds about 240 kilometers per hour. That’s faster than most tornadoes, and it’s been rapidly intensifying since Thursday,” he says at the fastest possible pace that can be understood. “Thursday morning had winds only 56 kilometers per hour. Just 24 hours later, more than 120—rapid intensification to a category one hurricane. Now it’s a Cat 4, almost a Cat 5.” His notes glow under dim overhead lighting, but most of what’s needed is in his head: The storm will miss the north Leeward Islands; waves will swell to about three meters offshore; those in the northern Lesser Antilles, Bermuda, Canada’s Maritime provinces, and the Avalon Peninsula will likely avoid significant damage. He glances down only to make sure he touches upon the season’s named storms (Grace, Ida, Larry) and the two left on the season’s conventional naming list (Victor and Wanda). After about six minutes, he’s thanked for his time. The energy in the car dissipates—a hurricane of enthusiasm easing away. “Anytime,” Cappucci says, “We just got back from bingo, so it’s been a fun night.”

Every day, whether he is working or not, Cappucci gets on his computer and pores over weather models. “You want to be almost intimate with the weather,” he explains. “The better you know the weather like a close friend…the better you are at your job.” Going through his typical process on a Saturday afternoon, he looks at infrared, visual, and water-vapor imagery taken from a satellite from above Hurricane Sam. He glances at the Global Forecast System model, operated by the National Weather Service, and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. Within moments, he can tell if a nice, sunny day is in store, or if the data demand a more exhaustive examination. On this Saturday, “There’s literally nothing going on,” he explains. The hurricane, swirling over the Atlantic, bothers only fish; temperatures in Washington are mild; wind is insignificant. Recording a radio segment from his apartment, he informs listeners that there is nothing exciting to report. “I try to be transparent,” Cappucci says.

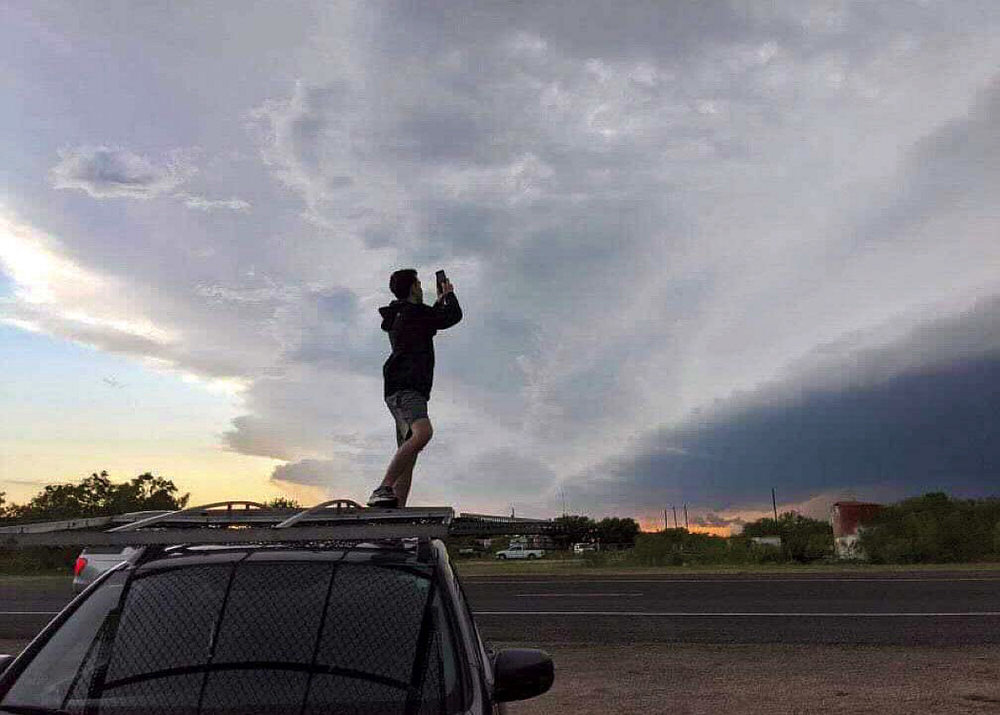

The leading edge of cool air “exhaust” from a thunderstorm in Rapid City, South Dakota

Photograph courtesy of Matthew Cappucci

But on severe-weather days, the process becomes all-consuming. Studying radar data becomes the last thing he does before he goes to bed and the first thing he does when he wakes up—often just a couple of hours later. “That’s when weather matters,” he says. “That’s the only time in our area that weather is going to be life or death.” The effort makes for confident forecasts even in unusual circumstances. In late August, Cappucci was one of the first meteorologists warning mid-Atlantic residents about the potential for tropical tornadoes—a rare occurrence in the region. As remnants of Hurricane Ida swirled northeast from Alabama, dragging a comma-shaped cold front toward the East Coast, a warm air mass moved northward from the South. Cappucci tweeted late Monday night that conditions were ripe for a tornado and later expanded on his forecast in the Post:

Working with an unstable atmosphere and abundant moisture, the approaching vortex has increased winds in the middle levels of the atmosphere. This belt of fast flow has increased the wind shear to 55-60 mph — quite an impressive value for early September. That deep shear is almost certain to organize thunderstorm cells into rotating types called supercells.

On Wednesday, a few minutes after taking promotional photos for Fox, he sprinted out of the building and drove east toward Bowie, Maryland, looking for tornadoes. Scanning radar imagery on his phone, he noticed a more eastward component to the surface-level wind in Annapolis, contrasting with the westward movement higher aloft. There must be spin in the area, he thought. With the warm, moist air from the nearby Atlantic and the heat from the sun, the atmosphere had enough energy for a major weather event. From years of chasing experience, he knew that wrapping clockwise above the spiraling storm system and tucking back westward into its inflow notch would give him the best view of the incoming tornado without getting caught in the funnel itself. When the tornado touched down, Cappucci was the only weatherman on the scene. He broadcast live to Fox, for the weather app MyRadar, and for stations across the world curious about the atypical storm near the nation’s capital.

Documenting an EF3 tornado from atop his armored truck near Sterling City, Texas

Photograph by Allen Chang

Meteorologists issue tornado warnings, but most don’t feel compelled to chase the storms, too. When Cappucci is providing a severe-weather forecast, he wants his audience to understand the gravity of the storm he’s describing, a sense he can only convey from having witnessed the events and their aftermath up close. “If you’ve never been out in the field…experiencing firsthand the elements you’re telling people to be safe from, it just seems distant,” he says. “And I never want to be a distant meteorologist.”

“If you’ve never been out in the field…experiencing firsthand the elements you’re telling people to be safe from, it just seems distant.…I never want to be a distant meteorologist.”

This enmeshed approach, and a desire to communicate the science to as wide an audience as possible, have helped make Cappucci a bit of a prodigy in the weather world. “He’s uniquely gifted in his ability to look outside, look up at the clouds, and explain what is going on in a very understandable and relatable way,” says Jason Samenow, the Post’s weather editor. “He just has a way of making very complex things both incredibly interesting, and also understandable.” While meteorologists have more information than ever from satellites and data-collecting instruments, they still use their judgment when making a forecast. Models are just that: two-dimensional, sprawled across a screen or piece of paper. “Weather models don’t have that human intuition,” Cappucci says. “They can look at data points we feed them, but they can’t look at the sky.”

The walls of Cappucci’s apartment are filled with pictures of storms he’s intercepted across the country, each with its own elaborate story. One was taken last May. As he was on his way to dinner with a friend during a storm-watching expedition in Kansas, he noticed a large gray cloud 30 miles away that went undetected on his radar. “I watched it though, and something caught my eye—a rugged strip of clouds at the bottom,” Cappucci wrote in the Post. “It was sucking in plenty of air, and the remainder of the cloud base was flat.” Something about its color and angle stood out; he felt compelled to drive after it. As he sped north, he came into contact with a low-precipitation supercell, which, within minutes, turned into a churning cylinder in the sky, rays of sunshine poking out from behind the half-mile-wide mass. He detailed the scene:

The storm’s eerie bowl-shaped updraft, illuminated by the setting sun, passed over me and to the south. Hail continued to fall, a few approaching lime size. Notice the cut of clear air into the backside of the storm — that’s the rear flank downdraft, a punch of cool, dry air, wrapping into the system.

For a few minutes, no one was around—just Cappucci and the spinning storm, an endless view of the Great Plains surrounding him. Hail pelted his car and lightning arced across the sky. “For nearly a full 30 seconds, I was fully relaxed,” he wrote. “That never happens.”

Catching up to a damaging tornado near Lockett, Texas.

Photograph courtesy of Matthew Cappucci

Cappucci has spent his life studying the atmosphere, but what keeps him going is seeing it in motion. “I get the atmosphere, I know what it’s doing,” he says. “But it has a personality. You swear sometimes it’s alive. Because just when you think you’ve figured it out and you know everything that it’s doing…it’ll throw you a curveball.…It’s science at its most sublime.”

On screen, on the air, and in writing, this genuine love for weather is always at the center of his presentation. “I don’t view my job as someone who just gives the weather,” he says. “I want to—as corny as it sounds—educate, inform, and inspire.” On unexceptional days when his forecast would likely be no different from what his audience could find on a weather app, Cappucci delves into topics he finds more interesting. One slow late-summer morning, he described why the fall season arrives with a distinct, crisp smell—tracing the scent of decaying leaves to Canada’s Hudson Bay, where an air mass looped through on its way from Saskatchewan. In early December, he explained, scientifically, why the sunrise looked like a hamburger. (An inversion—an increase in temperature with height—bent the light to make the sun appear boxy. A very thin cloud marking warm air “advection” spanned the diameter of the boxy sun, resembling a meat patty.) On Twitter, he posts frequent videos explaining curious cloud formations, extra-vibrant sunsets, and severe-weather events. Friends know if they ask Cappucci why the sky looks a certain way, they might receive a two-minute-long video explaining the clouds’ journey from the Great Lakes to eastern Massachusetts.

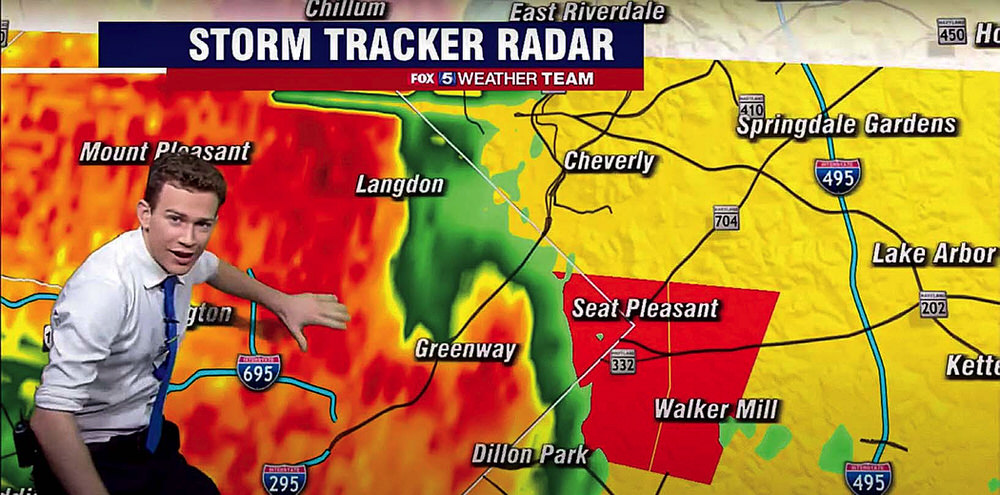

On his first day live at Fox, Cappucci found himself unexpectedly covering multiple tornadoes—his specialty.

Screenshot provided by Matthew Cappucci

This zeal for weather and gift for explaining it have made him one of the most prominent voices in the world of weather. In the generally tenuous field of meteorology-related media, he has an on-air job in one of the top TV markets in the country, contributes frequently to international broadcasts, and writes daily for the Post. On Twitter, where he posts constantly, he has 27,000 followers who respond spiritedly to his updates on the weather and goofy travails from his life. People rave about him on Reddit message-board threads, send him emails about how hearing his voice on radio makes a big city like Washington feel like a small town, and tell him they watch all his videos with their kids. Mothers ask if he would be interested in dating their daughters. The enthusiasm of his fans matches the enthusiasm of the man. “He’s the most obsessed person I’ve ever met when it comes to weather,” says Jason Samenow. “Most people who go into meteorology knew from a pretty young age they wanted to do this…but he has this stamina and this drive and passion and energy that is practically unheard of.”

Cappucci discusses the potential of an offshore low-pressure system.

Screenshot provided by Matthew Cappucci

Among the most common first words for babies are mom, dad, hi, bye, and dog. One of Matthew Cappucci’s first attempts was “anemometer.” Before he had the verbal dexterity to pronounce it (settling for “wind meter” instead), he obsessed over the spinning instruments on people’s roofs, pointing them out to his parents, wondering what they were measuring and how. His father, noticing his son’s keen interest, showed him a tornado documentary on PBS. He was hooked. By the time Cappucci was six, the elementary-school librarians in his hometown of Plymouth, Massachusetts, knew where to direct him. “We had a little row, probably a foot and a half long, of weather books,” he says. “And I went through all of them in two or three months.”

His mother, Kathleen Cappucci, remembers the flood of books that prompted an ever-evolving collection of weather obsessions. And though she and her husband—a nurse and an architect respectively—didn’t understand the source, they supported their intense son in any way they could. “Anytime a storm was approaching, we would hop in the car and go,” she said. “He wouldn’t think twice about waking us up at two o’clock in the morning to go chase a storm so he could go take pictures of the lightning and just watch it come in.” Cappucci was amazed by the swirling sky, the evolving show taking place thousands of feet above. The motion of the atmosphere was too beautiful, too elegant to pass up.

When he was eight, he used his Communion money to buy a video camera so he could record these storms. He scavenged golf balls to buy a laptop. With both secured, he bought a big piece of felt at Joann Fabric and sewed it into a green screen. “And it wouldn’t be that uncommon that you’d go down in the basement and Matthew would have his computer and some camera and everything set up a specific way,” his mother says, “so he could see what he was like in front of the green screen.” He started making full sample broadcasts, using PowerPoint to create graphics he’d insert onto the background. His eighth-grade science teacher, Karen Runyon, still keeps a Cappucci weather report in which he explained how tornadoes form and how they differ from waterspouts, and gave the five-day forecast for his middle-school classmates. “Thursday’s going to be the pick of the week,” he says in the video, wearing a bright yellow polo shirt and glasses, “perfect for our field trip.”

But Cappucci was alone in his obsession. He was friendly with his classmates, but there were no weather fanatics. His family didn’t share the passion, either. So he found some weather friends at Howard University’s annual weather camp in 2012. “Whenever there was a thunderstorm,” Cappucci said during an interview at an American Meteorological Society (AMS) conference years later, “Everybody was outside, everybody was at the windows, everybody was recording videos.” And he realized something else: among 12 weather nerds, he was by far the nerdiest. “But by virtue of that, for the first time, I was the popular kid,” he says. When it was thundering, everyone flocked to his dorm to ask questions. “We’d pore over the radar together,” he says, “and we’d run outside at the first sign of thunder and lightning.” He remembers the thrill of being appreciated for his passion—the sense of joy he felt from teaching others who really wanted to learn. “If I go to college for this, I’ll have this all the time,” he remembers thinking. “I figured I’d be with other weather folks in a weather department,” he explains. “And you know, have people with whom to geek out. That’s what made me excited for college.”

Before he even got to college, though, he had begun making a name for himself in the weather world. After completing an independent research project and submitting it to the AMS, he was invited to present as a student speaker in 2013, when he was 15. (After his mother encouraged him to apply without mentioning his age, and he was accepted, she told him to let the organizers know he was a high-school student and not a doctoral one.) He presented for every remaining year of high school, becoming, essentially, the society’s precocious mascot.

Cappucci wanted to go to then-Lyndon State College, a Vermont school with a respected meteorology program and a history of sending its students into the field. He got in, but then applied to Harvard and Cornell. Cornell had a known meteorology program. Harvard didn’t. He was accepted to both, and upon visiting, didn’t like either. His parents helped persuade him to at least try Harvard. If he hated it, they said he could transfer to Lyndon.

If he was going to go to Harvard, he was going to get everything out of it that he could. During his freshman year, Cappucci approached Eric Heller, Lawrence professor of chemistry and professor of physics, to ask if he would advise him on a special concentration: atmospheric sciences. Harvard has an earth and planetary sciences concentration, but he felt there were certain classes that he didn’t need. Heller—who recognized Cappucci from a Plymouth newspaper column he had written years earlier on the 1938 New England hurricane—agreed to help. It was not much work, he explained: Cappucci had already picked out four years of classes by himself, nine of which required him to cross-enlist at MIT.

“I am not a TV person. I am just a nerdy, geeky kid.…A lot of folks develop a radio voice, a TV voice. I just have my personality.”

Cappucci briefly joined the badminton club, where he was soundly defeated by much more skilled members, but never joined another undergraduate organization at Harvard. He was too busy. In addition to his courses in dynamic meteorology, atmospheric chemistry, and seismology, he worked between 30 to 40 hours a week tutoring and freelancing for The Washington Post. With money from work, scholarships, and grants, he bought recording equipment and outfitted his truck with hail-proof shutters. Finals fell during tornado season, so he asked nearly all his professors to allow him to take exams remotely. If the request was denied, he’d leave his vehicle in the Great Plains, fly back to Harvard for the exam, and fly right back so as not to miss any extreme weather. He graduated in 2019, but didn’t attend Commencement: he was in Oklahoma, on the hunt for tornadoes.

Cappucci applied for on-air weather jobs, and received offers in Portland, Maine, and Oklahoma City, but turned them down to work at the Post. Though he wanted to get on television, he didn’t want to confine himself to a small market. Instead, he built a name for himself through frequent freelance broadcast work on CBC News, the BBC, and World Is One News. He posted all the clips on YouTube, alongside hundreds of segments that he made specifically for his followers across social media, where he quickly built a large, devoted following. When he applied for a Fox meteorologist opening in June 2021, he sent along with his reel a 135-page document of fan testimonials: emails, tweets, comments on his Post articles. He got the job, which he completes, as is customary, alongside five others. In his scant free time, he wrote a book, “Looking Up,” to be published by Simon & Schuster in August—a few days before his twenty-fifth birthday.

Everywhere he goes, his earnest weather nerdiness shines through. Instead of discussing the five-day forecast for a full 45-second TV segment, he’ll explain why the evening sky is a stunning shade of orange. He tosses in technical terms like PWATs [Precipitable Water Indices] and isotherms, and quickly explains why they matter. “I am a professional, but I’m not professional,” he explains. “I am not a TV person. I am just a nerdy, geeky kid.…A lot of folks develop a radio voice, a TV voice. I just have my personality.”

Sitting at a table on the roof of his apartment building in Alexandria, Virginia, Cappucci explains that he picked his current home for its unobstructed westward view, high vantage point, and proximity to train tracks (another childhood obsession). “I wish that the apartment itself were a little bigger,” he admits, but the view is more important. As he sits, he sees a rainstorm in the distance. Asked what’s in store, he goes off for 90 seconds on the approaching “popcorn shower.”

A speech like this could only come from Cappucci. It’s not just the sheer knowledge—assembled and organized over two decades of study—or the timeliness that comes from the dozens of radars he looks at each morning on a half-dozen forecasting sites. It’s mostly that he bothers going into this much detail at all. The listener may not quite comprehend the subtleties of the interaction he describes between the cold front coming from the west—spanning Detroit, Nashville, and Mobile, Alabama—and the leftover moisture from a dissipated tropical depression, Nicolas. Nor can he quite imagine, in the moment, how all this low-level moisture is being forced up the Blue Ridge Mountains and the high terrain of North Carolina and southwest Virginia. But the magic is that the listener now wants to know. He wants to read the books Cappucci’s read, to understand how the clouds formed and why, to understand the complexities of the radar patterns. If it could make Cappucci this excited, surely it’s worth investigating.

Cappucci heads inside just before the rain begins and stares out the window in his building’s lounge. A few minutes later, his guest points to a particularly squat rainbow in the distance. “Oh, there’s a hint of a double-rainbow out there,” Cappucci says. “Ah, let me go do a quick explainer video.” He walks back onto the patio and, without any preparation, begins taking a selfie video in which he explains why the rainbow is so low for his Twitter followers. “The higher you have the sun, the lower you have the rainbow,” he says in full-on Cappucci excitement mode. “This is pretty much the lowest around here you’ll ever be able to see.” After he’s done, he comes inside and sits down, staring out at the landscape before him. “So many people are buried in their phone all day,” he says, “They don’t look up.” He estimates that the rainbow video will get about a dozen retweets, a bunch of views. “But there are things I’ve posted here before that get 200 retweets, and people say, ‘Wow, I’ve never seen that!’ I’m like, ‘It happens all the time! You just have to look up,’” he says. “So many things that if people would once in a while look up—they’d be amazed at what they saw.”