A year and a half ago, in the early months of the pandemic, Houghton archivist Dorothy Berry began a project to digitize materials from the library’s collection related to African American history and culture. This January, the finished product made its public debut, when Houghton unveiled a website and database of more than 1,100 primary sources (with more being added in the coming months), dating the slave trade through the early twentieth century: books, letters, photos, pamphlets, manuscripts, and numerous other artifacts. Accessible to both scholars and the general public, the website includes interpretive essays—written by Harvard graduate and College students—and contextual guides to help visitors navigate the collection, as well as teaching aids for middle- and high-school classes.

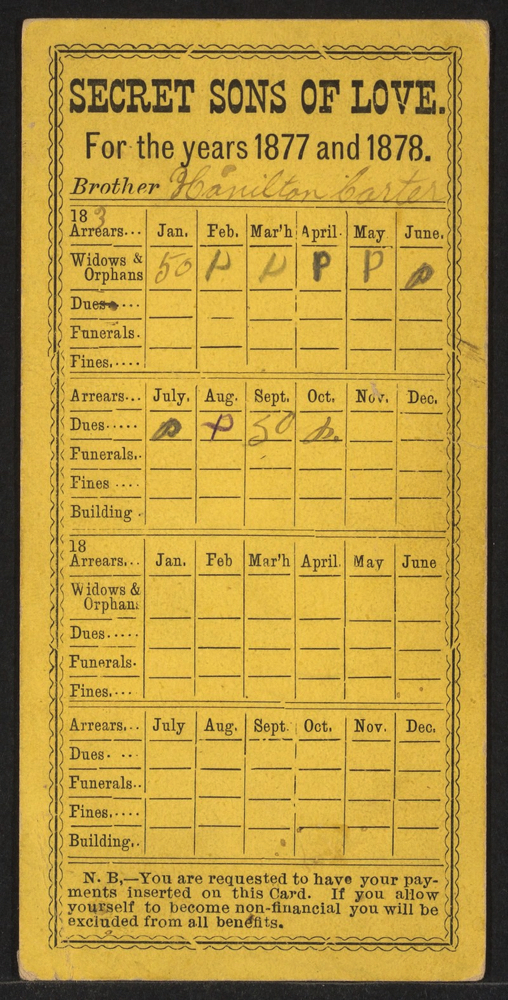

The curated collection, called “Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom: Primary Sources from Houghton Library,” is the first of its kind from Houghton. It includes artifacts ranging from the famous—letters and manuscripts from abolitionist Frederick Douglass, books by W.E.B. DuBois, Ph.D. 1895—to the obscure. “Hidden gems,” says Berry, Houghton’s digital collections program manager, whose professional background is in African-American-focused archival work. One of her favorite artifacts in the collection is a dues card for the Secret Sons of Love, a benevolent society for black men in Richmond, Virginia, that helped bury the dead and care for widows and orphans. According to the card in Houghton’s collection, Brother Hamilton Carter had paid up his annual membership dues for the years 1877 and 1878. “I love these neat and unexpected little fragments of existence,” Berry says—evidence of people living their everyday lives, even as huge historical forces swirled around them. In the 1870s, as Reconstruction was beginning to give way to Jim Crow laws in places like Richmond, “Hamilton Carter was paying into the general fund for the Secret Sons of Love, making sure that he’s giving money to the widows and orphans,” Berry says. “That’s what I often get passionate about in history, just thinking about objects as people interacted with them. That human element.”

Secret Sons of Love (Richmond, Va.). Financial account card (dues) for Hamilton Carter : DS (by Hamilton Carter), 1877-1878.

Carter family papers, MS Am 2322/Houghton Library, Harvard University

Another, related document in the collection is a certificate of merit for “deportment and diligent attention to studies,” awarded to Mattie Carter, a student at Navy Hill School, in 1883. Both the certificate and the dues card come from the Carter family papers, housed at Houghton; the Carters, Berry says, were middle-class African Americans. The father of the family worked jobs as a dining-room servant, and later as a servant to a physician. “They were just this family of regular people, living in the former capitol of the Confederacy 20 years after the Civil War,” she says. And artifacts like these help viewers see people like the Carters not just as figures who were subject to the violence and oppression of their era, but as “full people who had interior worlds,” Berry says. “A little girl who was maybe proud of her school certificate.”

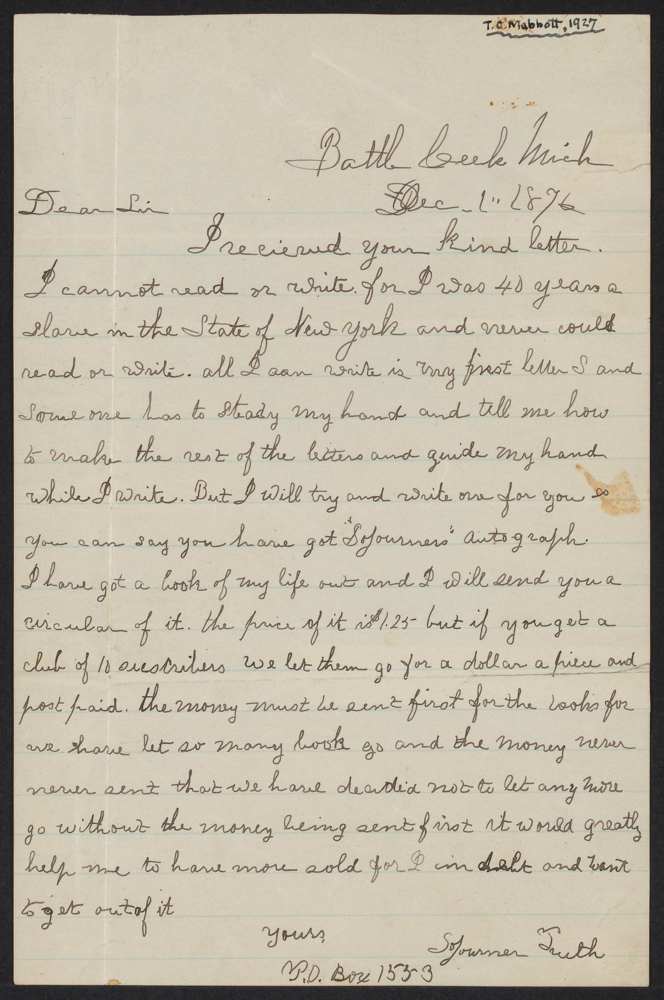

Truth, Sojourner, d. 1883. A.L.s. to [Thomas Ollive Mabbott]; Battle Creek, 1 Dec 1876.

Autograph File, T./Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Many of the artifacts in the collection give Berry that same kind of feeling, including ones that are attached to more famous names. One is a letter sent from Sojourner Truth in response to a person who had written her asking for an autograph. “A fan letter, basically,” Berry says. The abolitionist and former slave never learned to read or write, but she explains in the letter—written in a wavy, unsteady cursive—that someone else physically guided her hand as she moved the pen across the page, helping her to form the letters she could not understand.

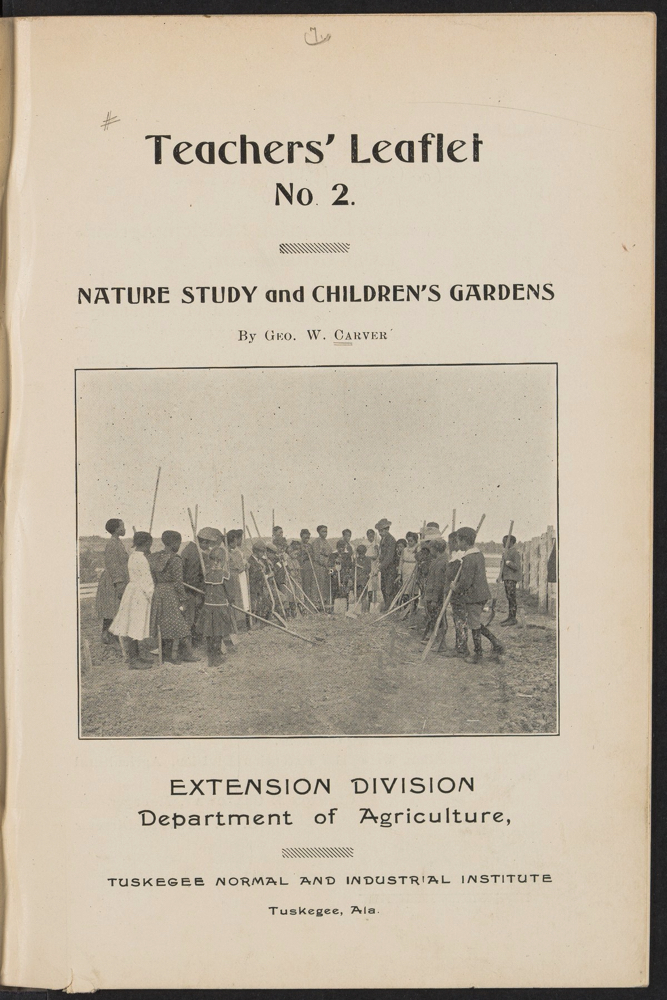

Another artifact Berry points to as full of “everyday, human possibilities,” is a pamphlet written by George Washington Carver, the scientist and inventor of peanut fame, and published between 1903 and 1906 by the agricultural extension division of the Tuskegee Institute. Titled “Teacher’s Leaflet No. 2: Nature Study and Children’s Gardens,” it is a guide to farm activities for youth and a how-to for starting children’s gardens. Page after page of photos show little girls in wide-brimmed hats and white dresses and boys in neckties and newsboy caps standing in the dirt holding shovels and hoes. “I’m always interested in the ways we can reimagine what diverse lives black people were living at these periods,” Berry says. “Because, I think most people would wonder why black kids would need a farming lesson, right? Looking back at the time period, the straightforward assumption is that black people are probably all still doing some sort of sharecropping or rural life. But even if it isn't a large amount of people, there are so many other contexts that are happening in 1903 or 1906. And so these kids are getting gardening lessons wearing little hats.”

Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 [author]. Nature study and children's gardens. Tuskegee, Alabama : Tuskeegee Normal and Industrial Institute, [undated, but after June 23, 1903 and before June 30, 1906].

Houghton Library, Harvard University

For those who want to seek out their own “hidden gems,” the collection’s website also includes a searchable, interactive dataset, which Berry hopes will be useful not only to academics conducting targeted research, but to the casually curious as well. “You can type in any keyword,” she says, like “Quaker” or “menu’’—both of which yield interesting results—and the tool will create a list of every associated artifact.

A similar ethos of curiosity runs through the teaching aids, developed by education consultant Mekha Aponte. She analyzed demographic data for both Cambridge and Boston public schools—which includes students from African, Caribbean, and South American descent—to create a series of classroom projects—oral histories, research papers, “discussion circles”—that draw out the role of the African diaspora in black history and culture. One lesson, for instance, asks students to construct their own family histories with whatever information they have, and to put them in conversation with some of the primary sources in the collection that correspond to the regions of the country or the world where their ancestors lived. “We wanted to build a foundation for historical literacy,” Aponte says, adding that she envisioned bringing archivists into the classroom as instructors. “Also, it’s important to say, the guide is not 100 percent prescriptive,” Aponte says. “It’s really a launching pad to think about how we can use special collections and the archives. We want to cultivate a community learning space, and primary source materials like the ones in this collection are a great resource.”