As Boston’s new mayor, Michelle Wu ’07, J.D. ’12, pursues her administration’s policies, Harvard and a recently formed Allston citizen’s group have each sent her letters, outlining competing visions for the development of the University’s 127 acres of contiguous undeveloped property in that neighborhood.

The neighborhood group’s letter echoed many of the concerns previously voiced by the Harvard Allston Task Force, an advisory body to the Boston Planning and Development Agency. In November, that group complained in a letter to President Lawrence S. Bacow that the University has not addressed relevant development issues in a comprehensive, neighborhood-wide manner. Instead, questions about affordable housing, transportation impacts, and community benefits, Task Force members said, have been handled project-by-project, with development partners taking the lead, rather than the University. Bacow responded to that letter in December, writing that he had asked Purnima Kapur, Chief of University Planning and Design, to supply the taskforce “with additional specifics in due course” in response to their questions and complaints.

Harvard’s most recent letter, signed by executive vice president Katie Lapp, was written in the context of a new administration in the mayor’s office—one dedicated to creating more affordable housing in a city with a desperately low vacancy rate. Lapp’s letter described significant investments in the community, and signaled the University’s willingness to make certain commitments in future developments. But it also suggested the limits of what Harvard might be willing to accept.

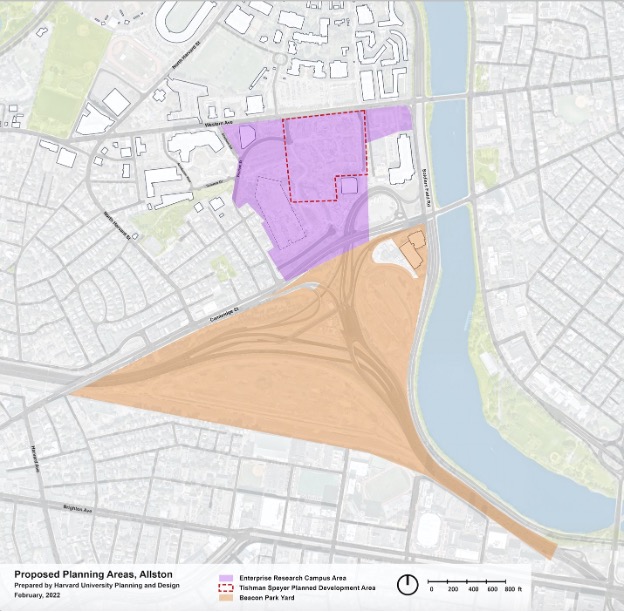

At stake in the near-term is the permitting of Harvard’s proposed “enterprise research campus,” a largely commercial project of retail, residential, laboratory, and office space, as well as a hotel and University-operated conference center, to be built by its development partner, Tishman Speyer, on 14 acres of land leased from Harvard. (The initial 9.4 acre “phase A” of that project is currently being reviewed by the Boston Planning and Development Agency.) Longer-term, the University hopes to develop the full 36-acres of this innovation district on what is now vacant land, formerly occupied by a trucking company (the 14 acres leased by Tishman Speyer will be the first part developed of those 36 acres). And a decade or two hence, once the state has straightened the Massachusetts Turnpike and improved the local highway interchange, the University hopes to develop a much larger parcel, the 91-acre Beacon Park Yard (BPY), formerly a railyard where freight was transferred to trucks.

Map depicting planning areas in Allston: in purple, the 36-acre Enterprise Research Campus (outlined in red is the 14-acre parcel on which development is pending); in orange, the 91-acre Beacon Park Yard, which cannot be developed until the Massachusetts Turnpike realignment project is complete.

Map prepared by Harvard University Planning and Design, as attached to Harvard University's letter to Boston Mayor Michelle Wu

Dueling Visions

Many of the goals articulated in the two letters—including commitments to open space, affordable housing, workforce development, and infrastructure improvements in transportation and climate resiliency—share significant overlap.

Lapp’s letter, dated February 23 and addressed to Mayor Wu, the Harvard Allston Task Force members, state representatives Michael Moran and Kevin Honan, and Boston City Councilor Liz Breadon, who represents the Allston-Brighton district, acknowledged “the community’s expressed desire to expand planning discussions…to the larger ERC district.” And it envisions a future planning process for the 91-acre Beacon Park Yard “consistent with the timing and scope” of the state’s turnpike realignment project, including a new rail and bus transportation hub. The letter explained that Harvard intends to continue using commercial real estate partners to develop the area, ensuring that they “conform with our commitments to the community” through the request-for-proposal (RFP) process.

But the letter from the Coalition for a Just Allston-Brighton (CJAB) includes stipulations that may not be feasible for Harvard’s development partners to meet. The letter draws a comparison to Stanford’s efforts to develop a large portion of its campus for institutional use in return for $4.7 billion in benefits to Santa Clara county. (Not mentioned is the fact that Stanford withdrew its permit application in November 2019, despite widespread voter support for the expansion and benefits package, upon determining that it could not meet some of the conditions—such as a no-growth cap on vehicular traffic—that were expected to be attached to the permit. In that sense, the parallels between the two situations are intriguing. On the other hand, Harvard’s proposed developments are commercial—not institutional—in nature, and extend beyond the perimeter of its existing campus.)

Lapp’s February letter to Mayor Wu outlined a series of commitments that Harvard is willing to make concerning planning, community engagement, open space, affordable housing, workforce development, and infrastructure improvements for these commercial developments. She pledged to:

- fund additional community benefits;

- allocate 20 percent of the land in the ERC zone as publicly accessible open space and make similar open-space commitments during future Beacon Yard Park development;

- fully fund and construct a $50-million high-capacity storm-water drain to reduce Allston neighborhood flooding during major precipitation events;

- donate land for affordable housing;

- ensure that 20 percent of the housing units in the ERC would be income restricted, as well as 20 percent of the units in the future BPY development, subject to conditions such as zoning relief for the former railyard;

- provide up to $10 million over five years for affordable-housing creation and preservation;

- ensure that a quarter of retail areas in future ERC projects will be reserved for local, small, and/or minority-/women-owned-business enterprise retailers;

- provide $1.05 million in new funding for workforce education programs in professional skills aligned with future ERC job opportunities;

- expand shuttle service and extend free riding privileges to ERC residents and employees (Allston-Brighton residents already ride the Barry’s Corner Express route free); and

- support the development of a multimodal transportation center in West Station, to which Harvard has already committed $58 million.

The commitments Lapp outlined in her letter are in addition to substantial investments that Harvard has already made in Allston, but they are unusual for commercial development. Committing to 20 percent open space, for example, makes sense in the context of a campus, but represents a very high level of open space for the kind of life-sciences development being contemplated in Allston. Harvard’s willingness to leave such a large amount of its acreage unbuilt may be explained, in part, by the possibility that some of these areas, 100 years hence, when the commercial ground leases are up for renewal, could be transferred to institutional uses.

The Community Letter

The letter from the Coalition for a Just Allston-Brighton (CJAB), undated and unsigned, articulates a desire for more engagement by Harvard—as opposed to independent developers—in broad community-planning efforts, and specifically asks for a more comprehensive approach to development planning, rather than one which proceeds project-by-project. The letter also highlights a variety of community development concerns, including:

- sustainability in development;

- transportation improvements that reduce reliance on cars;

- creation of linked green spaces to form an open-space network;

- expansion of Harvard-led educational initiatives;

- preservation of the Allston artist community through income-restricted live/work units; and

- educational and training programs “that will enable better access to well-paying jobs within the life-sciences industry.”

In addition to these general issues, the CJAB letter makes specific demands of Harvard and its development partners in the areas of retail and commercial space and housing. The letter asks Harvard to designate at least one-third of retail/commercial space in each development as affordable, and reserved for small-scale Boston-based businesses, with a percentage allocated to minority- and women-owned businesses. And in terms of housing—the biggest ticket item, and a pressing issue for Mayor Wu, given Boston’s one percent rental vacancy rate and stratospheric rent rates—the letter stipulates that:

- Harvard “must ensure that one-third (33 percent) of all housing units within residential developments built on Harvard-owned land in Allston and Brighton are income-restricted units available at area median incomes ranging from 30 percent to 80 percent” in perpetuity; and

- Harvard and its development partners should fund a community land trust that would promote the creation of affordable homeownership opportunities to counter Harvard’s construction of rental residential units.

Harvard already funds a homeownership program in Allston that has been operating since 2016. With $3 million in funding, the program has been used to buy houses on the open market, then repair and resell them with a deed restriction that stipulates that they must be owner-occupied. Proceeds from the sale of these units are then recycled back into the fund to finance new purchases. The program has so far purchased more than 20 units of housing, mostly former rentals that are now permanently owner-occupied.

While Harvard is clearly committed to affordable housing, whether development partners would consider the commitments in CJAB’s letter economically feasible is an open question. At present, Boston requires that 13 percent of housing in new residential developments be affordable. Phase A of the ERC will include 17 percent affordable units, while phase B, and future developments, will include 20 percent affordable housing. At stake in CJAB’s request that one-third of the housing built on Harvard land be affordable is potentially billions of dollars in rental revenue over the life of Harvard’s leases to developers.

Overlapping Objectives

In the letters to Mayor Wu from Harvard and the neighborhood coalition, there are significant thematic overlaps, particularly in the areas of sustainability, transportation, open space, workforce development, and affordable housing. These suggest that reaching mutually beneficial outcomes may be possible.

But there is at least one issue, footnoted in Lapp’s letter to Wu, on which Harvard appears to draw a line: the legal designation of its open space. Harvard’s long-term plans, a hundred years or more from now, may include conversion of commercial areas to campus spaces. As such, its commitments to open space assume that public easements will not be imposed, since that would hamper any future campus-development efforts.

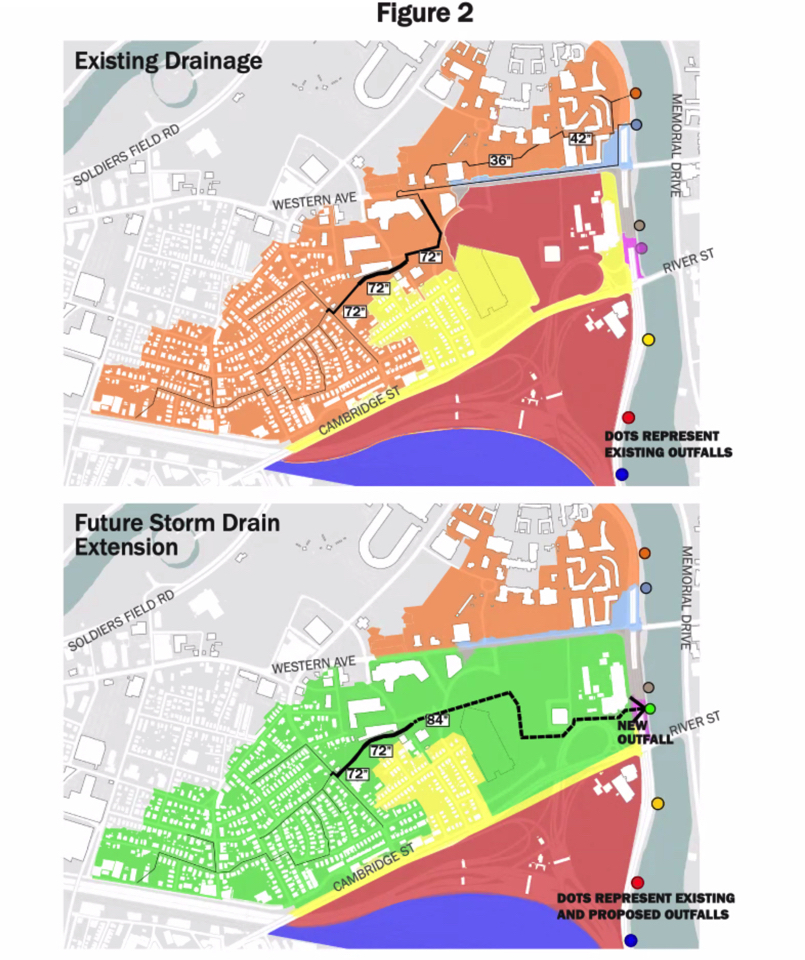

Above: the existing storm-water drainage pipe servicing North Allston drops from 72 inches in diameter to 36 inches on its way to an outfall pipe into the Charles River. Below: the proposed new extension would connect to an 84-inch pipe, and help prevent phosphorous-laden sediments from reaching the river.

Courtesy Harvard University

A case in point: Harvard has offered to fund and construct a new outfall pipe from Allston to the Charles River, as noted above. The new system would reduce flooding in the neighborhood, and also handle water from the ERC, which will otherwise be piped into the existing storm water system (see map)—clear public benefits. But in order to construct the new pipe, Harvard will need legislative approval, because the pipe will pass beneath parkland along the river. The new system would improve exclusion of phosphorous-laden sediments from the storm water, thus helping reduce pollutants entering the river. But legislative approval may not be forthcoming, because the pipe as currently planned runs beneath the ERC, and is therefore seen as a bargaining chip in community negotiations over the advancement of the ERC project. (Constructing the system as currently planned may not be possible once the ERC is built.)

In this impasse, ironies abound: the amendment to the state constitution that grants legislative control over parklands like that along the Charles is designed to protect land and easements taken or acquired for certain purposes, including “the conservation, development and utilization of the agricultural, mineral, forest, water, air and other natural resources” from being converted to other purposes. In this instance, the act may prevent a public-interest project that would improve the health of the river.

Harvard and its development partners thus find themselves navigating an increasingly complex planning and permitting process, in which the City of Boston, the Massachusetts legislature, and local residents will all play a role, against the background of the city’s continued growth, severe housing shortages, and other fraught issues.