As Harvard pursues ambitious development projects in Allston, residents fear that their neighborhood—which they describe as uniquely hospitable to families, immigrants, and artists—will come to look a lot like Boston’s Seaport district: a sterile landscape of laboratory buildings and luxury housing that skews wealthy and white.

Wary as they are of a Seaport imitation, area residents see great potential in the hundreds of acres Harvard is poised to transform: “It’s a blank canvas: the envy of any urban planner,” Tim McHale said. “The dreamscape is here in front of us.” They just don’t want the opportunity to be squandered: according to Jessica Robertson, “We have one chance to get it right. And so with this huge opportunity, there’s also huge stakes.”

As Harvard-related projects sweep from the Charles River toward Central Allston, local stakeholders have the chance to negotiate and collaborate with the University through the 15-member Harvard Allston Taskforce—an advisory body mediated by the Boston Planning and Development Association. But a number of Taskforce members have said they can’t engage meaningfully in the planning process when Harvard withholds a full vision for the entire area, instead soliciting their views on piecemeal proposals.

“You have an institution that controls a third of the land in Allston, and obviously that will have an enormous impact on what our community’s gonna look like for generations to come,” said Anthony D’Isidoro, president of the Allston Civic Association. “We have a right to know what the big picture is, the full vision is. And that’s like pulling teeth right now.”

Harvard’s Large Footprint

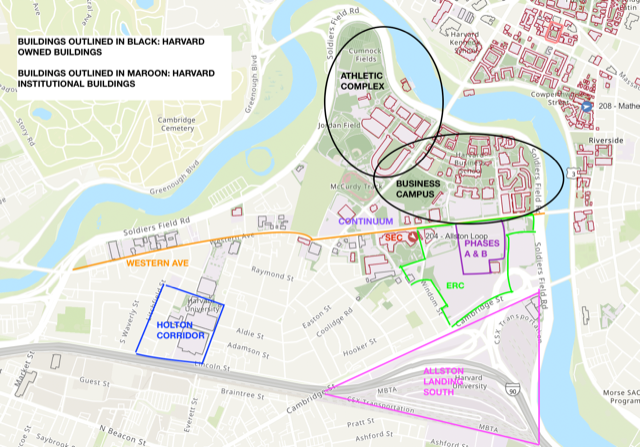

The University’s Allston holdings, totaling approximately 360 acres, include the Soldier’s Field Road Athletic Area and the Business School campus—both of which have long been Harvard-occupied. With its newly completed Science and Engineering Complex (SEC), the University enhanced its institutional presence to the west—and also brought its institutional acreage (as opposed to commercial acreage) up to 178 acres.

Watch a video showing the areas in Allston most likely to be affected by future development.

Harvard has attempted to invigorate the area around the SEC by dedicating several of its properties to a street-art initiative, and renting buildings out to Swissbäkers and Stone Hearth Pizza (the latter now closed, and subject to future development). Farther down the street from the SEC is the Continuum, which sits on Harvard-owned land leased to the development company Samuels and Associates. Completed in 2015, the Continuum boasts a Trader Joe’s, Starbucks, several restaurants, and 325 residential units. It’s pricey: monthly rent for a studio exceeds $3,000, while a three bedroom goes for nearly $6,000 a month—more than $70,000 a year for a family-sized unit. Across the street from the Continuum is 180 Western Avenue, another Harvard-owned parcel leased to Samuels and Associates. The site will eventually host more retail and restaurant space, as well as about 250 additional residential units.

West of the two Samuels developments, Harvard owns more than two dozen properties on—or clustered around—Western Avenue, which begins east of the Business School, intersects with North Harvard Street beyond Harvard Stadium, and then goes on to a second crossing of the Charles river at the Arsenal Street Bridge, where it enters Watertown and becomes Arsenal St. It’s unclear which of the properties along Western Avenue Harvard plans to redevelop, and how soon, but the Holton Corridor—a parcel bordered by Holton, Litchfield, Everett, and Lincoln Streets—seems to be an area of immediate focus. Contained within the Holton Corridor is 176 Lincoln Street, a 5.2-acre site Harvard leases to Berkeley Investments. The company plans, as of now, to construct two commercial buildings with office and research space, as well as one residential building with about 250 units.

Key Harvard holdings and corridors in Allston

Map images courtesy of Harvard University; overlays by Juliet Isselbacher

In the other direction, to the east of the SEC, the University’s future Enterprise Research Campus (ERC) will take shape. The imagined “innovation district” is a 36-acre undertaking—the first 14 acres of which are being spearheaded by the development company Tishman Speyer.

Finally, just south of the ERC, Harvard controls the 91-acre Allston Landing South. The parcel—described by Boston’s Architectural Heritage Foundation as a “no-man’s land of heat, dust, and noise”—will be opened up, perhaps in a decade, by a state project to straighten the Massachusetts Turnpike viaduct and reroute other transportation infrastructure that now cuts through it. University spokesperson Brigid O’Rourke recently told The Harvard Crimson that the plans to unlock the parcel will enable “new economic development potential for the region.”

From Academic Use to Commercial Development

The high-rise, market-rate, commercial development unfurling throughout Allston is a far cry from the way Harvard originally envisioned its plans for the land, which was to be dedicated to academic use, and which residents could reasonably expect to keep in scale with the existing community. The initial proposal, officially promulgated in 2007, included an enormous science complex; new education and public-health campuses; cultural and performing-arts facilities, including new sites for Harvard’s museums; and undergraduate and graduate housing.

The plan aspired to a “collegiate and community environment,” and reflected on how to integrate the Allston development with the existing neighborhood: “graduate housing can be a useful transition between the institution and the neighborhood,” the document explained, noting that “it makes sense to provide more public uses—retail, theater, museums—where the community can best access them.”

In 2009, President Drew Faust paused construction of the sciences complex—the first stage of the endeavor—as the University reckoned with the Great Recession. Twelve years later, Harvard eventually realized a redesigned version of this sciences complex, now the SEC. But it since appears to have abandoned its other major plans for an academic and arts hub, in addition to student housing—at least for now—in favor of a pivot toward private-market development.

The current trajectory has left residents concerned about how their neighborhood—already facing diminished homeownership opportunities and a declining number of families, and still recovering from the Turnpike expansion in the 1960s—will be further altered in the coming years. Also distressing to residents is that Harvard’s flurry of activity is attracting coattail developers, who need not coordinate among themselves or the community.

For example, down the street from the future ERC, a team of developers is working to transform Stadium Autobody and nearby parcels into NEXUS—a biotech and residential complex of more than half a million square feet. Continuing down Western Avenue, there is the former Skating Club of Boston, which a developer plans to replace with more than 600 residential units. Beyond are the Radius apartments, which were finished in 2019—complete with a mindfulness meditation room and pet spa.

According to Brent Whelan ’73, “There is a ‘new’ Allston taking shape along Western Ave [and] the Holton corridor…a world of modern and expensive apartments (very few condos), increasing lab space, higher-earning professionals, not much community.”

Pointing to the plans for the Enterprise Research Campus, which portend expensive apartments and towering, 8-10 story lab spaces, Whelan says the forthcoming innovation district “would seem to define a very concentrated version” of the ‘new’ Allston. He predicts it becoming “an enclave of highly productive, lucrative privilege”—one that has little relationship to or continuity with the existing neighborhood. That existing neighborhood is the ‘old’ Allston, he said: a landscape defined by two- and three-family houses, and populated by immigrants, a shrinking group of “multi-generational, mainly white working-class” families, and an increasing number of low-income service workers, artists, and recent graduates living in “transient” roommate groups.

“If the ERC will be truly integrated into the old Allston,” Whelan added, “it’s not clear how.”

A Community Confronting Change

Whelan is part of the Harvard Allston Taskforce, whose role to review and comment on Harvard’s local development currently focuses only on the first, 9.4 acre phase of the ERC proposal: a hotel and conference center, as well as 345 residential units, office and lab buildings, retail and restaurant areas, two acres of public open space, and 3.4 acres of “enabling infrastructure.”

The adjacent Phase B, though still conceptual and subject to change, may include an additional 4.5 acres of developable area. But that second phase—let alone the rest of the 36 acres—is not subject to Taskforce review until a specific proposal is put forth for regulatory oversight, even though it obviously has potential for equivalent impact. It is this context—newly dense and upper-income development, on which the community can have a say only through its commercial developer (Tishman Speyer), rather than directly with the landowner (Harvard), and only on a project-to-project basis—that is stirring Allston residents’ concern.

Taskforce members said they at least need to understand Harvard’s vision for the full 36-acre ERC before offering feedback on Phase A—a mere sixth of the entire area. So the University agreed to update its ERC Framework Plan, originally crafted in 2017, to address general principles and aspirations for the entire development. Harvard shared the updated document with the community at public meetings starting in January 2021.

“Harvard’s Enterprise Research Campus Framework Plan provides a high-level context for circulation, public realm, infrastructure, and other systems in and around the ERC, which all connect to the broader geography and adjacent planning areas in the region,” stated Marika Reuling, the managing director of Harvard’s Allston Initiatives. “Along with Harvard’s approved 10-year Institutional Master Plan (IMP) which outlines the University’s institutional plans, the ERC Framework Plan offers a long-term planning outlook for the full ERC district, and has evolved through many years of review, public discussion, and the evolving planning and development landscape.”

“Importantly, you’ll find in the document that we’re also clear about what we don’t know—and that as projects are proposed, the planning will evolve and be refined and inevitably change over time,” spokesperson Brigid O’Rourke noted.

But Taskforce members say the plan comes up woefully short. “I can’t imagine how you could put out 180 pages that said less,” Bruce Houghton said at an October Taskforce meeting.

What Taskforce members are struggling to understand, they say, is how (or even if) the ERC will be integrated with the existing neighborhood—especially because the Framework Plan does not discuss Harvard’s properties to the west, which run from Western Avenue’s intersection with North Harvard Street to its end at the river, and which would link the future commercial campus to Central Allston.

According to Houghton and others, Harvard’s “piecemeal” approach to development is not the answer to achieving an integrated Allston.

Housing: The Focus of Friction

A locus of residents’ concern is housing—understandably, given Boston’s perennial status as among the nation’s most expensive residential markets. It’s not apparent, Allston resident Jessica Robertson said, how Harvard plans to “bridge the gap” between the existing neighborhood—mostly two-family homes—and the “really large, really tall buildings” that will populate the ERC. “What can we do in between?” she asked.

It’s just as much about achieving continuity of community structure as physical structure, she added. Allston is home to many families, among whom “there is a real strong desire to have a unit that feels more personal and feels more like a house, rather than an apartment in a giant building.” For that reason, she said, it will be important to develop “mid-size housing typologies,” such as row houses, that can draw people with children into the area.

Stakeholders say Harvard will also need to prevent a wealth gap from opening between the old and the new Allston as well-salaried scientists, researchers, and business executives populate the ERC.

In Phase A of the ERC, Tishman Speyer has committed to making 17 percent (higher than the city-mandated 13 percent) of the 345 units affordable according to City of Boston standards, which define an “affordable” unit as one accessible to households earning up to 70 percent of the area median income. The rest of the apartments will go for market rate, which is “really high,” Whelan said (see the Continuum rents, above). “It will only be people making six-figure salaries who will be able to afford those market-rate apartments that they’re mostly building. So the whole thing is skewed in the direction of building a privileged enclave,” he continued. “People who’ve typically lived in Allston will not find a home there either to work or to live unless the ratios are changed.”

According to Tishman Speyer, it intends to offer a higher degree of affordability in Phase B of the ERC: 20 percent of the 420 residential units. “What Tishman has suggested is that the laboratory spaces that they will create [in Phase A] will eventually be lucrative, to the point where they will subsidize higher numbers of affordable units,” Whelan explained, going on to stress that this plan is “speculative.”

Jason Desrosier, manager of community action at the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation, said the deferred commitment to higher affordability concerned him. If the market for the commercial space declines, he said, then Harvard and the developer might not follow through: “The process of kicking the can down the road until a later time doesn’t benefit anybody.”

This potential for promises to fall through is the issue with planning Harvard’s Allston developments piecemeal, said Jo-Ann Barbour, who directs Charlesview, Inc.—a nonprofit that seeks to promote the “diversity and vibrancy of the Allston-Brighton community” through housing initiatives and social programming. In 2007, Charlesview, Inc. made a land swap deal with the University, trading its parcel at the intersection of Western Avenue and North Harvard Street—the former site of the Charlesview Apartments, an affordable-housing complex at Barry’s Corner—for a larger Harvard-owned parcel farther west along Western Avenue, where it rebuilt and expanded the housing project.

Given the success of this land swap, Barbour said, Harvard “could be much more visionary around what properties they might be able to offer up” to nonprofit developers in the community.

“It feels like Harvard is acting as a developer. And so each deal has [its] own little bit of housing attached to it. And so what the community ends up having to do is fight to get any level of affordability because they’re working with for-profit developers,” Barbour continued. “It’s this piecemeal approach that has all of us concentrating just on each development at a time…that makes it difficult to achieve any real goal around affordable, stable housing for folks in the community.”

“We’re just kind of eking out projects–you know, four at a time, without the big vision,” Tim McHale echoed. “I think the Taskforce is operating somewhat blindly.”

As a former construction-management consultant, McHale said he understood Harvard’s mindset: “Developers just don’t want to race into things, they want to build a little, test the market, see how it’s going, and then build again,” he explained. “So I totally get Harvard’s pragmatic approach to a series of developments. We, on the other hand—in the neighborhood—we want to see it all. And so there’s the friction point.”

The Framework Plan didn’t do much to advance stakeholders’ understanding of what housing will look like throughout the ERC, Taskforce members said. In fact, it does not go further than to promise a total of more than 1,000 units of housing, at least 13 percent of which will be affordable, according to Boston requirements.

“We understand there may be 1,000 units,” Whelan said at an October meeting. “But when we ask what the inclusivity of those units will be, we’re told, ‘Well, who knows, these are unplanned.’ So the sense that there is no larger overriding vision is what is a little distressing to me and other members of the Taskforce.”

Barbara Parmenter, a Taskforce member and former lecturer at Tufts University’s Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning Department, said she hopes to see a plan that promises 20 to 25 percent affordable housing—if not more—across the ERC and the surrounding area, as well as room for community land trusts, cooperative housing, and other types of innovative social housing.

A November 10 letter to President Lawrence S. Bacow, signed by 13 of 15 Taskforce members, asserted, “Allston/Brighton could be a living laboratory of housing innovation. [But] the current process in Allston of ground leasing parcels one by one to private developers leaves no room for such innovations.”

“As is, the current proposals state that housing affordability will meet the bare minimum [income] requirements for Boston, which not only fails to inspire, but produces cynicism and hostility in a neighborhood whose median income is well below that minimum,” the letter continued. “Clearly private/public/university partnerships will be necessary to mitigate the housing crisis, and a fuller discussion with Harvard’s housing experts would at least begin this conversation.”

Whelan said he is uncomfortable with Harvard’s resistance to having that fuller discussion. “My imagination tells me that Harvard is building [a] type of very modernistic, very technology-driven piece of the city. And it’s incompatible with Allston, so they don’t really want to talk about it too much,” he said. “It would not be a very heartwarming discussion in the neighborhood.”

If Harvard does not intend to make the “new Allston” continuous with the “old Allston,” he said, then perhaps the University could instead “do more to shore up the existing neighborhood where it stands, instead of just letting it sort of erode into the overpriced housing market.” Harvard does work to bolster affordable housing options in Allston through the All Bright Homeownership Program, and in the Greater Boston Area through the Harvard Local Housing Collaborative and its contributions to the City’s Housing Linkage program.

Whelan specifically proposed that Harvard provide subsidized housing on its many properties west of the ERC along Western Avenue. The problem, he noted, is that “so far those other properties have been entirely decoupled from Harvard’s Master Plan or ERC Framework.”

This snag exemplifies the complaint that Taskforce members have consistently leveled against Harvard: they can’t engage meaningfully with the planning process when discussions are so limited in scope, excluding land that could prove potentially relevant in productive negotiations. It’s hard to evaluate whether specific proposals are “good or bad because we have no idea how they fit into the larger picture,” Whelan said.

Harvard did, in fact, donate a parcel at 90 Antwerp Street (in the Holton Corridor) for the construction of a recently-completed affordable housing project, and also committed to making a parcel at 65-79 Seattle Street (at the edge of the ERC) available—for free—for homeownership development.

“More small gestures could add up to a large gesture,” Whelan said. Parmenter noted that they’d like to get a sense of how all these gestures will add together up front.

“After pushing and pushing and pushing, at the end of the [Taskforce] meeting in July, Harvard said, ‘Oh, we’re gonna make this parcel at Seattle Street available for affordable housing,’” Parmenter recalled. “We were like, ‘Okay, so that’s something. [But] can we just have a vision for…the larger picture on housing?”

In a December 6 response to the Taskforce, Bacow wrote that the University agrees “there is real urgency in making substantive efforts to address equitable and affordable housing in our region.”

“I am proud of the ways Harvard has led in this area over the last several decades,” he continued, citing the Harvard Local Housing Collaborative and the donated Seattle Street parcel.

Open-Space Options

In a March comment letter on Phase A of the ERC, the Boston Parks and Recreation Department (BPRD) affirmed the need for holistic thinking, writing that Harvard’s holdings in Allston afford “a unique opportunity to create a comprehensive system of open spaces that relate to one another and serve as the framework around which the new neighborhoods can develop.” There is an opportunity, the letter continued, “to provide a world-class open space system for a large area of the city on a scale not seen in Boston since the creation of the Emerald Necklace.”

Map showing the envisioned “Greenway” that will one day connect Ray Mellone Park to the Charles River

What Harvard has proposed is an open-space corridor, called the Greenway, that would connect the Charles River to Ray V. Mellone Park, which sits on Harvard-donated land adjacent to the Honan-Allston Branch of the Boston Public Library. The Greenway would cut through—and extend past—the ERC to run parallel with Cambridge Street for a half-mile.

Though impressive, the Greenway is insufficiently visionary, the BPRD wrote. Harvard needs to think beyond this one corridor, the letter stressed, and consider how it will serve the entire area that it will eventually develop. “That’s just one discrete portion of the hundreds of acres that they have control over,” said BPRD executive secretary Carrie Marsh Dixon. “What the Parks Department’s letter proposes is that there be a system of east-west and north-south open spaces…”

Whelan commended the BPRD for “imagin[ing] the ERC as the beginning of a much larger course of development that would take us several decades down the road” into Allston Landing South, and also down Western Avenue to Market Street.

He and a dozen fellow Taskforce members wrote in their November letter to Bacow that they join “the Boston Parks and Recreation Commission in calling on Harvard to plan greenspace first, so that development weaves around a green resilient network, rather than buildings coming first, forcing greenspace to go into ‘pocket parks’ and ‘sidewalk rooms.’”

In his response, Bacow wrote, “Harvard is, and has been, a strong steward of open, accessible, welcoming green space, and that approach is embedded in our planning. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in Harvard’s updated ERC Framework Plan document, which contains principles that guide our planning and directly address these issues.”

Planning Piecemeal

Though the BPRD letter spoke to Harvard’s Allston holdings overall, it was technically a comment on Phase A of the ERC—and so the duty of responding went to Tishman Speyer, the project’s official proponent. According to Parmenter, Tishman Speyer declined to engage with the letter, since it invoked properties beyond their scope. “That incredibly thoughtful letter from Boston Parks and Rec just dies in the file somewhere,” she explained. “It’s just frustrating.”

Whelan described the situation as a “shell game where the developer [is] being used to insulate Harvard” from reckoning with feedback: “It says, ‘No, no, no, it’s Tishman Speyer’s proposal—we just happen to own the land.’”

“That hide-and-seek game that we’ve been playing has been very frustrating, and it’s not the first time,” he continued. “[The] Continuum was developed in exactly the same way. Harvard owned the land; it leased it to the developer. When the developer produced the plan, Harvard was nowhere to be seen… They're doing it all over again at 180 Western Avenue, the same type of apartment development.”

In their November letter, Taskforce members wrote that Harvard is also shirking its responsibility for comprehensive transportation planning, delegating the job to Tishman Speyer. “The current level of transportation planning, largely left to the private developer, is completely inadequate for such a scale of development. Tishman Speyer focuses on transit, bike, and pedestrian-friendly infrastructure within the Phase A and B project boundaries, which is what they are mandated to do, and they are doing that thoughtfully. However, consideration of the project without a wider regional perspective risks obscuring the very real and large-scale interventions that will be required.”

“We are discussing the construction of 100 acres of mid-rise buildings—100,000 employees, residents, and shoppers. And there is no comprehensive transportation plan,” echoed McHale at a September Taskforce meeting. “We are just putting our finger in the dike, here, with widening and narrowing [streets].”

“Anything like the ERC needs to have regional planning,” said Anna Leslie, the director of the Allston Brighton Health Collaborative. “[If] the hope is to craft another Kendall Square [the dense life-sciences and technology development across the Charles River, adjacent to MIT], in terms of its academic or intellectual impact, how are folks getting to and from this region?”

The local commuter-rail line and bus routes are at capacity, she pointed out, and the MBTA bus and subway system “is on the brink of collapse”: “How on earth do you plan to continue to move people to a space with a system that is at capacity, and not contribute to that system?”

Harvard spokesperson O’Rourke noted that the University has pledged up to $58 million toward the state’s construction of the future Western Station commuter-rail stop in Allston Landing South, which sits below the ERC. “West Station has the potential to serve as a multimodal hub, not only for Boston, but also the region,” she wrote. “It will provide…connections that have never before existed due to the impermeable nature of the former rail yard use.”

Community Building

From a developer’s perspective, of course, planning and building a little bit at a time is often necessary, given the investment involved and the risks. Bill Cummings and Dennis Clarke ’90—founder and CEO, respectively, of the Woburn-based Cummings Properties—drew on the company’s 50 years of experience developing more than 11 million square feet of commercial real-estate space in the suburban Boston market to explain the advantages of a piecemeal approach.

“By the time [Harvard] get[s] the first phase done, years will have gone by, certainly—who knows what the thinking will be by the time they get into the second phase of it? It’s almost impossible to know ahead of time what the best use is going to be,” Cummings said. (His company is not involved with Harvard’s development projects.) “To be constricted by something that is said…in an agreement or a covenant today for what is going to get built there never mind five years from now, maybe 10 years from now, would seem to be an enormous task without being too productive.”

“To try to tackle something that big all at once wouldn’t seem feasible, even if you wanted to,” Clarke affirmed.

Though devising a comprehensive network of greenspace is, in fact, realistic, they said (as well as an excellent opportunity to make efficient use of land that is difficult to develop), housing and transport plans are probably best left to devise parcel-by-parcel. Evolving needs in those areas are easier to assess in real-time—whether 15, 20, or 30 years hence.

Yet, some Taskforce members don’t believe that Harvard is really hedging its bets. “They have a broader vision—I am convinced,” D’Isidoro said. “They know what they want to do in all 36 acres of the Enterprise Research Campus. They’re probably already doing visionary work for Beacon Park Yard [in Allston Landing South]…the problem is they don’t want to share that vision with us, for whatever reason.”

Clarke said the Cummings company reckoned with similar distrust when it developed a 65-acre site in Beverley, Massachusetts. “Early on the local community felt that we were holding out: ‘You folks must know what exactly what you want to do. You’re just letting it out in small dribs and drabs because you don’t want to tell us.’ Well, that couldn’t have been further from the truth. We reimagined different parcels on that site for residential versus commercial versus life sciences. And we’ve done it building by building and it’s worked quite well.

“One part of the site that we had earmarked in the early years for multi-unit residential is now the home for the North American headquarters of a tech company that’s doing advanced manufacturing,” he continued. “Beverly is thrilled to have a major employer up there. But if we were gambling, we would have gambled that was going to be residential.”

Clarke said Allston stakeholders “are starting out with a perspective that Harvard’s interests are inherently different or adverse to theirs.” In his experience, he added, “It’s just the opposite”: “Real estate, at the most fundamental level, is about community building. If you have really architecturally nice and expensive buildings, but they’re not in an area that people want to live, work, and visit, you don’t have value—you’ve got liabilities.”

It’s no surprise, though, that Allston residents are dubious about whether Harvard’s interests align with theirs. There’s a longstanding “dynamic of distrust” between the two parties, according to Robertson. “I’ve been here for about 10 years,” she said. “When I moved to the neighborhood, the relations between Harvard and the neighbors were pretty contentious.” She explained that Harvard had “gotten off on the wrong foot” with the community after it secretly purchased land using shell companies beginning in the 1980s.

“No one realiz[ed] that it was Harvard consolidating such a huge amount of the land in Allston,” she explained. “It hasgotten a little better over the years…There’s a lot of great stuff that’s happened. But everyone is always sort of starting off by being a little bit suspicious about what Harvard is up to and what they’re not telling us.”

This distrust reared its head during the October Taskforce meeting, during which members criticized Tishman Speyer for distributing a petition to residents. The petition reads, “I support Tishman Speyer’s proposal…this project will provide benefits that Allston needs: new open space that will help connect the Allston community toward the Charles River, and more affordable housing.”

“That is not the community engagement that we asked for,” Whelan said at the meeting. “We asked for a serious negotiation, not an attempt to sort of hustle up support by presenting a one-sided view of the proposal.”

Outside of the meeting, Whelan specifically criticized Harvard and Tishman Speyer for directing so much community focus to the Greenway and its attendant programming. “They have used the Greenway as a shiny thing to hold up and attract people’s attention,” he said. To him, he added, it seems like “a very deliberate plan to get us focused on little stuff we could get from the program rather than what the larger program will do in terms of really creating a new piece of the city.”

Nupoor Monani, M.A.U.D. ’15, a senior institutional planner and project manager with the BPDA, acknowledged that Taskforce meetings can sometimes become diffuse, as members redirect conversations about Phase A of the ERC to broader questions about the future of their neighborhood.

“It tends to go in a bunch of different directions, and I completely understand that. This is a large, very, very complex project in a much larger planning study or planning framework,” she said. “Sometimes professional planners can have a hard time wrapping their head around these issues and concepts and so I’m very empathetic to the communities that are wanting to talk about everything and not necessarily being able to stick to the two different lanes.”

“North Allston is one of the most planned areas in the City of Boston,”O’Rourke wrote. “There are many efforts happening simultaneously, with many different stakeholders, all with the common goal of creating and supporting a robust, vibrant, and inclusive Allston Brighton. Each of these areas has its own specific regulatory processes, and Harvard has continuously been at the table supporting these conversations when appropriate.”

Bacow wrote in his letter that he has asked Purnima Kapur, Harvard’s chief of University planning and design, to supply the Taskforce “with additional specifics in due course” in response to their questions and complaints.

“We are all committed to creating a district that the University and the community can be proud of,” Bacow stated. “We will continue to work collaboratively with the city, elected officials, and the Allston-Brighton community to further explore many of the important issues that we’ve heard about through the ongoing community-feedback process.”