When the conversation turns to frogs, wildlife artist Bradley Scott Davis ’97 starts talking faster. “Now, this guy right here,” he says—pointing to a recently completed painting on his studio wall, loosely abstract and thickly textured, depicting a green-and-yellow frog covered in dark spots, gazing up at the viewer through liquid-black eyes—“this is called a barking tree frog. From the Hylidae family. Herpetologists will tell you that this is the handsomest frog in all of North America.” Davis grins, lets that disclosure sink in for a moment. “Which isn’t saying much,” he continues, “because there are only about 100 species of frogs in North America. Somewhere like Ecuador, you’d find that many in just a small area.”

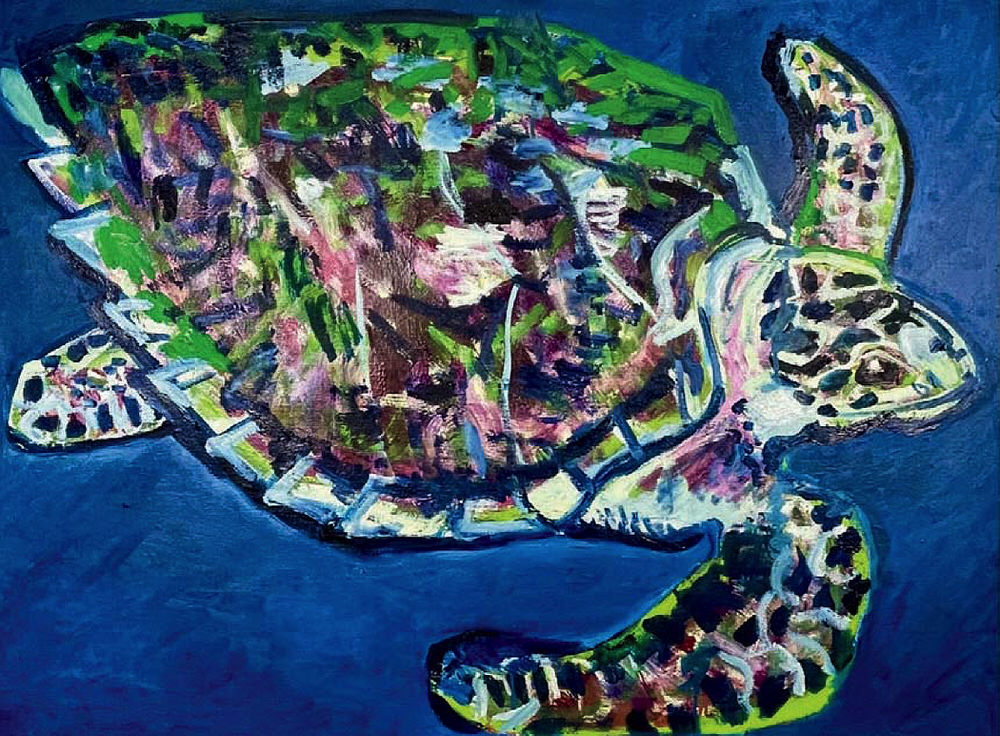

Atlantic Hawksbill Sea Turtle, (2017)

Paintings courtesy of Bradley Scott Davis

Nevertheless, he thinks the herpetologists might be onto something—the pleasingly plump body, the striking black markings, the darkly prismatic eyes: “They’re not wrong.” Davis’s favorite species, though, is the less celebrated gray tree frog. Rumpled and diminutive, and rarely seen except during breeding season, they emit a mating call so musical that it can sound almost like a bird’s song. When Davis was growing up outside St. Louis, his family kept a swimming pool at the edge of the woods. Every summer, armies of gray tree frogs would come down from the high branches there to mate. The males would set up by the pool and begin singing—“loud,” Davis recalls—and the females would seek them out. “As a kid, to see all these tree frogs having a ball, to be witnessing this wild event,” he says, “it was amazing.”

A painter who has shown and sold his work across the United States, Europe, and New Zealand, Davis is now based near Minneapolis, in a studio whose walls are covered with animal paintings—frogs, but also wolves, deer, lions, tigers, fish, and birds of prey, plus the occasional dog or turtle or bear. His work feels ardent and vigorously alive, with bold colors that sometimes depart from nature’s palette, and paint layered on so thick in places that the images seem actually to emerge from the canvas.

Wild Indian Tiger, (2014)

Painting courtesy of Bradley Scott Davis

It took Davis a while to figure out that he was an artist, but he always knew he was a naturalist. Recalling the frogs in the trees above his childhood swimming pool, he’s suddenly reminded of a lecture by E.O. Wilson, on the rich biodiversity in the rainforest canopy. As an undergraduate, Davis took classes with the legendary Harvard biologist, who died in December; later, Wilson became a friend and source of inspiration. Davis’s own trip to the rainforest, on Costa Rica’s Osa Peninsula—“one of the few places with a viable and large population of wild scarlet macaws”—was momentous. The story he tells about that visit involves bees, vipers, peccaries, a poison dart frog, and the “hypnotic” song of a toucan, which Davis followed deep into the forest, until he was far off the trail and at the edge of a cliff, lost and clinging to a thorn-covered tree, watched by howler monkeys. “A beautiful day,” he says.

Davis’s work often focuses on conservation and environmental degradation, particularly climate change and habitat loss—both major threats to amphibians, especially frogs, which rely on delicate, disappearing ecosystems that straddle water and land. “One of the reasons I paint so prolifically and with such a passion,” he says, “is because there’s an urgency in the message of the art, and an urgency to capture what’s being lost.” He remembers Wilson’s call, amid shrinking biodiversity, for scientists to work even harder to identify and study unknown species. And Davis isn’t only focused on frogs. Two larger paintings, of a male lion and a cheetah—both adapted from images by wildlife photographer Anup Shah—place the animals against a richly colored background meant to signal a dangerous disharmony threatening the earth’s environment: wide ribbons of green and blue, edged by red.

Wisconsin Wolf (2009) painted in the Northwoods.

Painting courtesy of Bradley Scott Woods

Davis arrived at Harvard intending to become a doctor like his father. He concentrated in psychology (and played on the men’s hockey team), but by the end of his four years had realized medicine wasn’t for him. Initially, he shifted to poetry, encouraged by a creative writing course with poet Henri Cole, and after graduation, he moved to Manhattan, where he tended bar at night and wrote during the day. He shared a loft with his brother and several friends, and a group of artists lived in the back half of the building, with whom Davis would chat. Eventually, he acquired a set of paints and began experimenting.

What happened next was a kind of possession, he says. As soon as he began painting—first teaching himself and later begging lessons from an artist acquaintance—everything accelerated. A still life of mangoes led to an expansive abstract mural on his bedroom wall, enveloping windowsills, exposed pipes, and parts of the ceiling. “The whole room was a painting.”

African Lion (2018)

Painting courtesy of Bradley Scott Davis

Davis got serious about depicting wildlife after he moved to the South Island of New Zealand in 2001. A cousin in Christchurch had invited him out, and he expected to visit only a few weeks, but stayed for more than a year, living in relative isolation, hiking the wilderness, swimming and kayaking, selling his paintings at local restaurants and coffee shops. The animals he encountered profoundly shaped his art. Once, kayaking in Flea Bay, he says, he met a pod of rare Hector’s dolphins. They swam alongside him, lifting their noses in what seemed like a greeting. That same evening, swimming off the beach, he found himself next to a yellow-eyed penguin. “So I’m like 10 feet away from this beautiful bird doing this crazy evening swim,” he says. “This is an animal that’s infrequently seen, even by birders. And somehow it found me.”

After New Zealand, Davis spent several years in Bristol and then Bath, England, where he studied painting at the Bath School of Art and Design. He returned to the United States in 2006 and lived and worked in the remote Northwoods of Wisconsin; his studio looked out over an often-snowy lake where wolves howled at night.

He and his family (his son, Darwin, is 13) relocated to Minnesota 12 years ago. As always, he watches the wildlife around him, including, and maybe especially, the frogs. (He dreams of traversing the country, documenting America’s frogs and toads the way Audubon painted its birds.) During the pandemic, he began a project called “The Daily Frog”: each day he paints a single specimen on an eight-inch-square canvas and posts a photo on social media. The idea, he says, is to “start conversations about conservation.” Until they’re sold, the paintings hang in rows in his studio—the barking tree frog is there, as is the gray tree frog. Recently, he hung another: a Great Plains narrow-mouthed toad, which sometimes shares a burrow, and a symbiotic relationship, with a particular type of tarantula: the spider fights off snakes and other large predators, while the frog protects the spider’s eggs from ants. “A wild story,” Davis says excitedly, looking up again at his wall of painted frogs, his voice rising again.