Picasso’s War: How Modern Art Came to America, by Hugh Eakin ’96 (Crown, $32.99). This learned, brilliantly written account explains how the European avant-garde came to captivate the American elite—as now embodied in that “hegemonic empire of art and money,” the Museum of Modern Art in New York, a “city-state unto itself” on whose board “sit more billionaires than are found in all but nine U.S. states.” The cultural conquest was far from inevitable, and Eakin’s explanation of the players and their roles might be extended to understanding any other momentous cultural shifts.

Blown Away: Redefining Life after My Son’s Suicide, by Richard Boothby, Ed.M. ’79 (Other Press, $24.99). It is one thing to read about the tens of thousands of deaths tied to addiction and suicide each year. It is another, entirely different and essential, to encounter an individual case. The author, professor of philosophy at Loyola University Maryland, recounts the loss of his son at age 23. His first, understandable reaction: “I wanted to shoot myself.” Not doing so, learning to go on, is the unavoidable, hard work left to the survivors, recounted here.

Megathreats, by Nouriel Roubini, Ph.D. ’88 (Little, Brown, $30). Not to pile on—what with inflation, war in Europe, the possible collapse of democracy worldwide, etc.—but the professional prognosticator adds several bricks to the load, outlining “10 dangerous trends” from “the mother of all debt crises” and the demographic time bomb (aging) to the “coming great stagflation” and an increasingly “uninhabitable planet,” and more. Roubini describes himself as “an economist attuned to upheaval.” And how.

The Biggest Ideas in the Universe: Space, Time, and Motion, by Sean Carroll, Ph.D. ’93 (Dutton, $23). The theoretical astrophysicist with a gift for explaining his field (he now holds appointments in physics and philosophy at Johns Hopkins) sets his sights high, dreaming of “liv[ing] in a world where most people have informed views and passionate opinions about modern physics.” The going isn’t so easy, but lay readers will admire Carroll’s success (in a book of modest scale, not so dumbed-down as to avoid formulas) in introducing hard-to-visualize concepts like black holes—without falling into one.

Death before Sentencing: Ending Rampant Suicide, Overdoses, Brutality, and Malpractice in America’s Jails, by Andrew R. Klein ’70 with Jessica L. Klein (Rowman & Littlefield, $36). Experts on probation and substance abuse in prison, and on rape and domestic violence, combine in a furious critique of “deadly jails” that have “largely avoided accountability for their lethal incompetence and irresponsibility.” They counsel that the long-term solution “is to stop using jails as warehouses for society’s most vulnerable”—the homeless, those with alcohol and substance abuse disorders or mental illness, trauma victims, and “those who are simply poor and can’t afford to buy their freedom.”

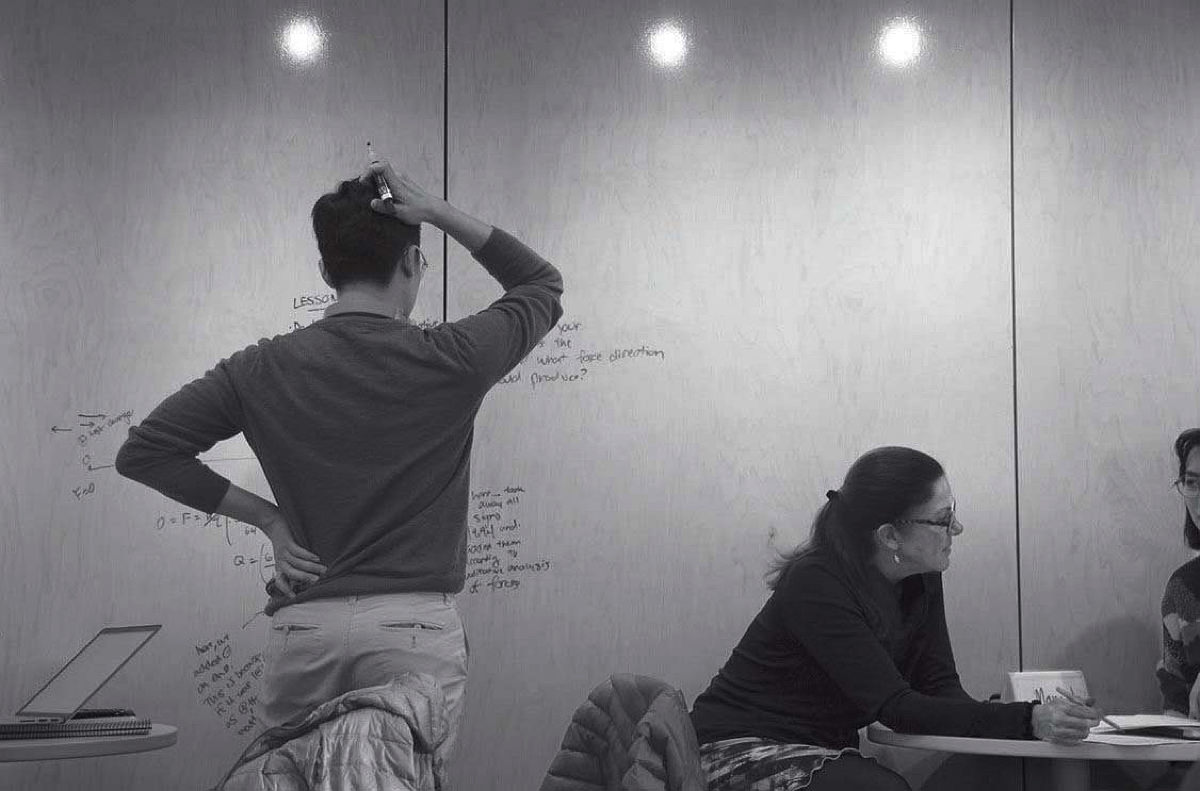

What Teaching Looks Like: Higher Education through Photographs, by Cassandra Volpe Horii, Ph.D. ’02, and Martin Springborg (Elon Center for Engaged Learning, $40.50 paper, or free by open access). Horii, Stanford’s associate vice provost for education and director of a teaching and learning center, and Springborg, who does similar work at the community college level, deliver a documentary-photography project that makes vividly real effective, engaged teaching. Anyone interested in better teaching can see, and not just think abstractly about, the human interactions that enliven the class setting: the magic of in-person learning.

What learning looks like: a student solves problems on a dry-erase wall—in this case, at a doctoral institution.

Photograph by Martin Springborg

Being There, by Peter Keese ’58 (WipfandStock,$16). The author, an Episcopal priest, recounts cases from his work as a Clinical Pastoral Educator counseling clergy on their practice. But the discoveries and lessons apply to life situations broadly: a broken relationship, coping with a disability. The cumulative effect of the brief sketches is humbling in a way many lacking contact with religious communities may find illuminating.

Never Turn Back: China and the Forbidden History of the 1980s, by Julian Gewirtz ’13 (Harvard, $32.95). In this book, written before he became China director on the National Security Council, Gewirtz probes the 1980s debates within the People’s Republic over liberalizing not just economic but political life—a discussion terminated by the 1989 suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests. He suggests that the “China model” of today, fueled by rapid economic growth and (ever-expanding) authoritarianism, need not have been the country’s path. That it has become so explains both the dangerous tensions between China and liberal democracies, and the Communist Party leadership’s need to maintain “immense historical distortion” to sustain legitimacy.

Making Americans, by Jessica Lander, Ed.M. ’15 (Beacon Press, $26.95). A young alumna of Princeton and the Graduate School of Education who has devoted herself to teaching history and civics to recent immigrant students at Lowell (Massachusetts) High School and elsewhere, examines immigrant education historically, in classrooms nationwide, and through her work with students. Past experience in educating and assimilating newcomers is, of course, no guarantee of future success, but Lander’s teaching, and her sense of perspective about what is required “to make Americans” (the first words in each chapter), seem more important than ever.

Plagues in the Nation: How Epidemics Shaped America, by Polly J. Price, J.D. 89 (Beacon Press, $28.95). “We expect government to keep us safe from epidemics,” notes Price, a professor of law and of global health at Emory. Not all agree during the COVID-19 pandemic. And indeed, she continues, “But the United States has a spotty record of doing so”—not only because of the pathogens, but because of “our deep culture of individual rights and constitutional values.” Looking back to 1776 and rounds of smallpox, yellow fever, polio, HIV/AIDS, etc., proves uncommonly edifying.

The Equality Machine, by Orly Lobel, S.J.D. ’06 (PublicAffairs, $30). What’s right with technology and artificial intelligence? Outside Silicon Valley, few people ask the question that way. Lobel, Warren Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of San Diego, does, beginning by recounting her daughter Elinor’s type 1 diabetes—and the smartphone apps that help safely track her blood-sugar level and insulin pump. She then crafts a sweeping call for designing technology and AI with quality and social benefit in mind.

Politics Inc.: America’s Troubled Democracy and How to Fix It, by John Raidt, M.P.A. ’02 (Rowman & Littlefield, $35). A former legislative director for U.S. Senator John McCain examines problems from the mercenary electioneering industry to the corrosive effects of money, but his central insight concerns the broken political culture. When “epidemic cynicism has conditioned the public to spy conspiracies, cabals, and coverups around every corner,” democracy has to cope with a fundamental problem: “So many people believe nothing they hear, and yet, paradoxically…are willing to believe almost anything.” One hopes the suggested remedies might work, without, perhaps, believing it.

Collective Illusions, by Larry Todd Rose, Ed.D. ’07 (Hachette , $29). The problems of “conformity complicity, and the science of why we make bad decisions” (the subtitle) are not new ones, but Rose mines the literature vividly, aiming to help readers “make better decisions,” “build better relationships,” and “have a more meaningful life, lived on your own terms”: a life that is individually and collectively more fulfilling.

Things That Were Made for Love: The Songsheet Art of Sydney Leff, 1924-1932, edited by Wyatt Doyle, Hal Glatzer, and Norman von Holtzendorff ’88 (New Texture, $49.95). A sumptuous collection of Jazz Age sheet music covers, created by one of its foremost artists. Von Holtzendorff is an avid collector of the genre, and Leff, a commercial artist who died in 2005 at age 104, the last of the great Tin Pan Alley illustrators, was a master of the form, justly celebrated in this initial volume on his work.

The New College Classroom, by Cathy N. Davidson and Christina Katopodis (Harvard, $35). Two scholars at the City University of New York apply insights from learning science, pedagogy, and practice to show how essentially every course can be made more effective through the proven techniques of active, engaged education. A decade and more into the work of the Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching (and after three years of pandemic-induced online learning), these insights ought to be, and perhaps are, filtering into the educational mainstream, here and elsewhere. It is productive and helpful for Harvard University Press to spread the word.

Harvard’s Quixotic Pursuit of a New Science, by Patrick L. Schmidt ’78 (Rowman & Littlefield, $40 paper). An undergraduate thesis, now amplified by correspondence, historical research, and secondary sources, charts the rise and fall of the Department of Social Relations, the revolutionary attempt to create a new interdisciplinary social science. Towering scholars like Talcott Parsons and David Riesman loom large, as do the intellectual stakes—and the personal and institutional factors that brought the department down.

Second time around: “Weather nerd” Matthew Cappucci ’19, profiled in the March-April issue (“A Weather Obsession,” page 42), has published Looking Up, a true-adventures account of storm-chasing (Pegasus, $27.95). Paul Dry ’66, himself profiled in “A Leap into Books” (November-December 2001, page 90), has released a new edition of When the Tree Sings, the novel by Stratis Haviaras, the long-time curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room and founder of The Harvard Review (Paul Dry Books, $17.95 paper). And J.F. Coakley ’68—formerly of Houghton Library, and proprietor of Jericho Press—has reprinted in elegant book form part of “Mr. Vlasov Meets the Ham King” (about an important work in Old Church Slavonic), by Rodney G. Dennis, former Houghton curator of manuscripts, originally published in the magazine’s March-April 1996 issue.