Editor’s note: Harvard Magazine published “The Market-Model University: Humanities in the Age of Money,” by James Engell and Anthony Dangerfield, in the May-June 1998 issue. A quarter-century later, the trends identified then have only intensified. Here, Engell takes stock of the humanities and arts, in the academy and in society, today.

“My dear son, I am appalled, even horrified, that you have adopted Classics as a Major. As a matter of fact, I almost puked on the way home today.” The recipient of the letter beginning this way attended Brown, studied the classics (and economics), and later remarked how pursuing ancient literature prepared him for competition, business, and philanthropy. Ted Turner won the America’s Cup, founded CNN, established the United Nations Foundation, and leaves indelible marks on media, conservation, and philanthropy.

President of Ireland for seven years, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights for five, recipient of the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom and a Harvard honorary degree, Mary Robinson, who studied law, now heads a foundation dedicated to climate justice. She continues to promote human rights globally. In 1998, reminding Harvard graduates of Eleanor Roosevelt’s work, she stated, “you are now…answerable only to yourselves with regards to your performance, your humanity and your soundness of judgment.…I ask that you use your education to pursue…the betterment of the lives of others.” She closed by quoting from Seamus Heaney’s poem “From the Republic of Conscience,” including these lines: “You carried your own burden and very soon / your symptoms of creeping privilege disappeared.”

The longest serving secretary of defense in U.S. history and then president of the World Bank, Robert McNamara later reflected that had he and others known the history and culture of the country in which they prosecuted a long war, such a conflict might never have continued to take millions of lives, tens of thousands of them American. He concluded that he and others had relied too much on metrics and quantitative analysis, all built, he said, “on an inherently unstable foundation.”

These three individuals followed—or came to recognize—an outlook on life and action deeply informed by the humanities.

Has democracy been trembling because we’ve slighted schools of government or ignored STEM? Without resonant historical knowledge there are no mystic chords of memory to touch. Already the better angels of our nature seem disbanding for lack of an instrument to play. Racism persists. Civility grows unfashionable. Antisemitism spreads. Lies on social media and internet conspiracy fantasies spark violence, even homicides.

In the face of this, the arts and humanities bring the whole soul into activity. They represent the external world but more—they represent our inner life and our conscience tested as we greet and grapple with that outward reality. In life as in academic disciplines, the arts and humanities, rightly conceived, draw freely from the single nectars of other fields to create a honey none alone produces. If we pursue collective good, shun venality, exercise empathy, and remain open to people unlike ourselves, then we are humanists all—each of us, as Lincoln said of his encounters with Shakespeare, an “unprofessional reader.”

None of this comes simply by osmosis from other fields. Dean Delphine Grouès of Sciences Po, a leading institution of the social sciences, is adamant that those sciences require the infusion of les sciences humaines, the humanities, including rhetoric as self-questioning critique: in what kind of society do we wish to live? As the Nobel laureate in physics Steven Weinberg said, science discovers many things—but “nothing in science can ever tell us what we ought to value.” And if we desire “diversity, inclusion, and belonging,” we are making a solemn pact with the arts and humanities, which most fully form the content of our character.

Teaching the arts and humanities well confers proficiencies such as good writing and clear speaking. Critical thinking emerges—take nothing on authority, absorb but question traditions, conserve in order to reform. Embracing past experience, the arts and humanities put current predicaments in perspective: achievements since ancestors set foot in Olduvai clay, alliances with evil, triumphs over disease, social contracts defeating brute force—all represented from the cave paintings of Chauvet to the caves of virtual reality.

The humanities welcome everything from Exodus to No Exit, Gregorian chant to country music: from high “culture” through graphic novels and TV series. Nor are fiction and aesthetics divorced from the “real world.” As Gabrielle Starr, president of Pomona College, observes, these efforts demand intricate observation, nuanced comparisons, and repeated attempts to organize the chaos of experience. In short, aesthetics and fiction continually solve complex problems. Engaging the humanities, arts, and history entails ethical questions, too, essential for developing self-critical motivation and judgment. Literature pursues not only written forms but phronesis, practical wisdom in the conduct of life; and sophrosyne, psychological balance, as in “work-life balance.” Daniel Webster praised such literary acumen in John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. It made them “more accomplished…for action in the affairs of life, and especially for public action.” It is akin to what President John Kennedy conveyed in his October 26, 1963, speech at Amherst College’s groundbreaking for the Robert Frost Library:

[W]hat good is a private college or university unless it is serving a great national purpose? The Library…this college, itself—all of this…was not done merely to give this school’s graduates…an economic advantage….It does do that. But in return for…the great opportunity which society gives the graduates of this and related schools, it seems to me incumbent upon this and other schools’ graduates to recognize their responsibility to the public interest.…

There is inherited wealth in this country and also inherited poverty. And unless the graduates…are willing to put back into our society, those talents, the broad sympathy, the understanding, the compassion—unless they are willing to put those qualities back into the service of the Great Republic, then obviously the presuppositions upon which our democracy are based are bound to be fallible.…

Robert Frost…brought an unsparing instinct for reality to bear on the platitudes and pieties of society.…[I]t is hardly an accident that Robert Frost coupled poetry and power, for he saw poetry as the means of saving power from itself. When power leads men towards arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses. For art establishes the basic human truth which must serve as the touchstone of our judgment.

The artist … becomes the last champion of the individual mind and sensibility against an intrusive society and an officious state.…

We must never forget that art is not a form of propaganda; it is a form of truth.

Civil rights, labor rights, women’s rights: all propelled by persons deeply acquainted with the humanities and arts. Maria Stewart, Rachel Carson, Mahatma Gandhi, Henry David Thoreau, John L. Lewis, John R. Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Rose Schneiderman: each immersed in literature, religion, poetry, history, biography, or philosophy—or several of these.

Harry Truman (no college degree) remarked that reading histories and biographies is essential preparation for leadership—a principle now applied at West Point. If citizens can’t read and listen critically, there’s no discerning a leader from a demagogue.

Many fortunate enough to enjoy the GI Bill after World War II (African Americans and women were often shut out) studied the humanities because they realized the necessity of such study for a better world. As in any field, a few humanists have been bigots. But the arc of the humanities has always been to expand the franchise, to involve a broader, more tolerant representation of experience, a visceral as well as intellectual rejection of might makes right, or that I stand superior to Thou. The arts and humanities are not sufficient for a decent, civilized society. But they are necessary.

The Crisis Is Over: Do Not Resuscitate?

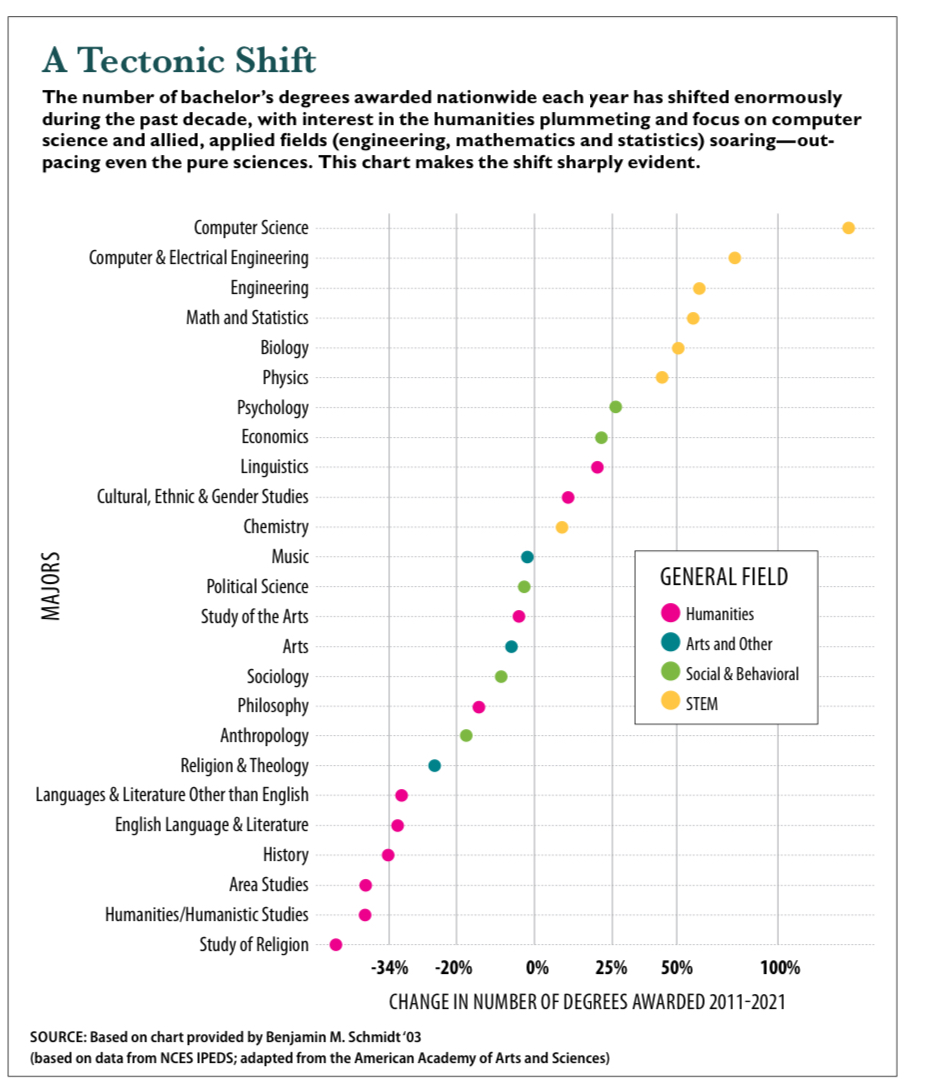

That is why continued disinvestment in the arts and humanities is costly and ominous. In the last 50 years nationally, the percentage of all bachelor’s degrees conferred that fall in the humanities dropped from above 20 percent to below 10 percent (at Harvard from close to 30 percent to about 10 percent). In the last 60 years, foreign language enrollments per 100 students in higher education slid from about 18 to 8. In the last 10 years, precipitous drops occurred in classical studies, history, religion (theology aside), foreign languages, and English, with significant reductions in comparative literature and philosophy. Music held steady. Ethnic and gender studies enjoyed modest gains. Overall, there are now as many or more computer science majors in the United States as in all humanities fields combined.

Concerned over these trends, computer scientist Harry Lewis, former dean of Harvard College, identifies one circumstance: “Given the state of secondary education in America …students will not arrive at Harvard thinking that the humanities are anything but an exotic luxury for the well-to-do.” According to a recent study, more than three-quarters of high school seniors believe that education strictly devoted to one job is the best higher education.

If what has happened to the humanities had happened to engineering, the sciences, or social sciences, administrative heads would roll.…The humanities are now on life support, especially reading-intensive and historical fields.

If what has happened to the humanities had happened to engineering, the sciences, or social sciences, administrative heads would roll. Teachers in the humanities and arts are tired of the word crisis. The crisis in the humanities lasted 40 years. It’s over. The humanities are now on life support, especially true of reading-intensive and historical fields. When will DNR be posted on the patient’s door?

Why Has This Happened?

First, surveys reveal a pervasive belief that college is simply a stepping stone to a particular career: occupational prep with extracurriculars. And many undergraduates attend colleges where little exposure to the humanities is required.

Second, success in competitions is how colleges select students in the first place. Given the lure of Amazon/Google/Facebook/Goldman Sachs/McKinsey salaries, the Great Recession, and other factors, students continue to seek rewards and security. The educational posture that disinvests in the humanities increasingly valorizes only what President Kennedy called a personal “economic advantage.” Accommodating that demand leaves little room to expand the students’ reach, to equip them to perceive underlying dysfunctions of society at a humane rather than an abstract, analytical level.

Third, colleges often treat students as consumers, and employers as commodities. Not enough teachers treat students as whole, ethical human beings. No wonder they feel anxious about belonging and inclusion.

Fourth, treated as consumers and commodities, students and parents believe the myth that studying the humanities, arts, and history neither shapes the mind nor prepares it for good careers. That myth is false, especially for students in selective colleges. According to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (AAAS) Humanities Indicators, in 2015 the percentage of bachelor’s degree holders in the humanities reporting they were “very” or “somewhat” satisfied with their jobs was higher than those with a degree in business or the behavioral and social sciences. Over almost 20 years, humanities majors aiming for professional school scored better than business majors on the GMAT and as well as majors in any other field. They scored in the upper ranks of the MCAT (only math and statistics students scored higher, not majors in biology or the physical or social sciences). Humanities majors scored almost as well on the LSAT as engineering, math, and science students, and considerably above majors from the social and behavioral sciences.

Do graduates in the arts and humanities earn less, on average, than those in computer science, engineering, and investment banking? Yes, initially, though after 40 years the lifetime earnings gap has substantially closed. A decade after graduation are they less satisfied? No, generally not. Arts and humanities graduates enjoy careers, sometimes lucrative, in medicine, law, government, business, journalism, consulting, finance, and the environment.

Fifth, those earning Ph.D.s in the humanities amass more debt than peers in science or engineering. Debt is highest for Black and Native American students. From 1990 to 2020 firm academic job placements for humanities Ph.D.s fell from about two-thirds to less than half. History suffered hugely. Humanities doctoral candidates need to rely far more on teaching assistantships than their counterparts in other disciplines. Bottom line: more debt, more work, fewer stable job opportunities.

Sixth, students at all levels aren’t blind to the inequalities and signals evident in their own institutions. Humanities faculty receive lower pay, incur more debt in graduate training, and generally enjoy less staff support than peers in other fields. Why study something that colleges and universities often treat as second class? So, students take fewer humanities courses, resulting in fewer faculty positions, more teaching by grad students or adjuncts, and so on.

Seventh, to be sure, this decline has occurred in part because of self-inflicted harms. The academic humanities, and to some extent the arts, often focus inwardly, pursuing microscopic research expressed in “professional” prose. Alfred North Whitehead warned that without an eye to some application, present or eventual, academic knowledge becomes inert. This danger also pertains to the humanities and arts, which should afford relevance or pleasure or both. If students and society increasingly regard the arts and humanities as irrelevant or merely amusing, then bigger questions of meaning, value, justice, and humane action fall by the wayside, lone hitchhikers hoping that other areas of study will pick them up.

That problem aside—and it is significant—three criteria we spelled out in 1998 remain an infallible guide to the prospects for investment in an academic field today:

• the promise of money (securing an occupation that promises above-average lifetime earnings), even though it may be false;

• the study of money, business, or finance; or

• the receiving of money from external grants.

Satisfy any of the criteria and using any measure—degrees conferred, faculty salaries, square footage added, alumni giving, etc.— and the field has grown relative to the mean of all fields. Fields not meeting any of the criteria have shrunk relative to the mean. As the three criteria continue their merciless sway, the academic disparities, already large, will inflict a high price on society.

The Price Paid

Society indeed pays a severe price for pulling the plug on the humanities and arts. Did we lose the Vietnam war, flail in Iraq, and occupy Afghanistan for two decades before letting it revert to the Taliban in two weeks all for lack of superior science, technology, engineering, or math? For lack of computers? Weapons? For lack of trillions spent? How many would have lived had our leaders known the history, religion, language, and culture of those countries? If ignorance persists, there will be more ill-conceived conflicts.

New technologies have not narrowed widening inequalities of income or wealth. AI won’t help unless guided by hands with some humanistic training. We would not have lost more than a million U.S. souls to COVID-19 had we paid attention to public health, the medical humanities.

For Earth as a whole, the environment still seems a low priority, always lagging some concern du jour such as gas prices. The climate science is in, and our delayed action makes it darker. Science alone (even bolstered by law and policy) can’t easily change attitudes and values. Galvanizing political will with degraded discourse is hopeless. Transforming scientific knowledge into solutions requires articulate public engagement, persuasion, and dead serious entertainment—mind and heart fused, a strength of the arts and humanities.

Weld professor of atmospheric chemistry James Anderson, who first verified the ozone hole and prompted the Montréal Protocol, says this about the lowered place of the humanities in higher education:

While it will take some time for me to emerge from a deep sense of concern (depression) underscored by…the current structure of university priorities…this development is particularly untimely given that the world is changing so rapidly—just the time when a deep understanding of human nature, of human complexity, of human motivation is most acute. It is profoundly disturbing to see that the treasured citadel of the university, guided by thought and wisdom garnered over the arc of time, is now at risk.

By minimizing the arts and humanities, higher education exacerbates the problems confronting society. No one can interpret difficult texts, write sound treaties, examine conflicting testimony, or cut a path through the divisive, frequently false claims on social media without language and judgment sharpened by the humanities. Absent such training, one is hobbled to develop the attention span required to fight obfuscation, or to resist online algorithms fiendishly designed to shorten attention still further.

Does knowing how to face, explore, and judge an unstable and culturally mixed world order matter? Do social cohesiveness and the ability to compromise matter? With no mandatory national or public service, do empathy with those unlike one’s self and conversations with fellow citizens matter? If not, goodbye to a functioning democratic republic.

What Lies Ahead

Faculty at Harvard and other institutions of liberal learning advise applicants not to decide on one course of study based on supposed earning power, presumed status, or apparent security. Study what you’re passionate about and leave room for new things, they counsel: what you do throughout your life will change. Books by Fareed Zakaria, Martha Nussbaum, Wendy Fischman and Howard Gardner, Helen Small, Mark Moss, and Mark Edmundson, among many others, superbly make the case for reinvesting in the humanities and arts. Economists increasingly promote hybrid education mixing hard and “soft” disciplines, quantitative plus humanistic. Research by Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa reveals that students do not improve critical thinking much by finishing problem sets or learning techniques that 10,000 others master. Students improve critical thinking by concentrated reading coupled with painstaking writing examined closely by demanding instructors. It takes a lot of time. It pays off.

Yet, students spend less time reading than 45 years ago, even 25. Most faculty outside the humanities do not evaluate student work to help improve the prose. “It’s not my job,” is heard frequently. Of course: it’s not rewarded one bit.

Within the humanities, administrators have developed a tiered teaching faculty as unequal as the society it is educating—and inequalities are growing: current practice in the humanities means that too often the harder and more time-consuming the work, the lower the compensation and security. Reform is overdue. Concomitantly, humanities departments and deans need to stop overproducing humanities Ph.D.s, a malpractice three decades long. Some universities treat newly arrived doctoral candidates as cannon fodder for teaching college composition and survey courses. The attrition rate is not low. Reform is overdue.

The humanities need to resist temptations to become ingrown and yet more specialized. Scholars might recall more frequently some common questions anchoring their fields: what does it mean to lead a good life, to do good work, to make the world better? How do we live through suffering and grief? Departments might open themselves to a full spectrum of ideological and political perspectives. In some institutions, especially so-called elite ones, an unspoken litmus test can exist.

In colleges and universities, as well as in the nation, a tiny additional fraction of the resources supporting engineering, biomedical, and other sciences would provide students and teachers in the arts and humanities with a sense of equity, inclusion, and belonging. Right now, many feel they are denied that, and morale is low.

But as the song goes, not “all the news is bad again.” More than ever, the academic arts and humanities reflect the entire nation and its diverse population. There are more opportunities for people from every conceivable background. New media and digital applications are enlivening the arts and humanities. By making undergraduate requirements look less like preparation for graduate work in the same field, some departments are attracting more students. UC Berkeley reports an increase in humanities majors. Used wisely, the internet affords creativity and publication without endless gatekeeping. Alternately, exhausted by the frantic pace of a distracted world, some students and artists are rediscovering slow time, craft, and patient art-making.

If the nation believes that economic benefits alone (vital as they are) suffice in our education, or that we can cultivate democracy at home and support national interests and human rights abroad without devotion to the arts and humanities, then our citizens will lack the knowledge, skills, and judgment—as well as pleasures—crucial for personal well-being and, yes, national security. This is what has been happening. There is peril in letting the arts and humanities become an endangered species. Such diminishment would be a loss for every citizen, and a danger to the nation.

Sources:

Michael O’Connor, Ted Turner: A Biography (Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 2010), 16-17. Ted Turner published his father’s letter, unattributed, in the Brown newspaper The Daily Herald.

Robert McNamara, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (New York: Vintage Books, 2017), 325; originally published by Random House in 1995.

Steven Weinberg, “The Future of Science, and the Universe,” The New York Review of Books (November 15, 2001): 58-63.

Harry S. Truman, “On Reading,” Post-Presidential Files, Desk File, Box 3; see also The Autobiography of Harry S. Truman, ed. Robert H. Ferrell (Niwot: University of Colorado Press, 1980), 115. At West Point Prof. Elizabeth Samet links literature to leadership in her teaching and publications. See Harvard Magazine March 24, 2016.

Sources for declines in degrees in the humanities comes from Benjamin Schmidt (American Historical Association and National Center for Education Statistics) and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, “Humanities Indicators.”

Harry R. Lewis, “Bit and Pieces” Blog, April 21, 2022 (harry-lewis.blogspot.com).

Scott Jaschik, “What are the Liberal Arts,” Inside Higher Ed, September 19, 2022, https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2022/09/19/new-study-asks-what-high-school-students-think-liberal-arts.

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, “Humanities Indicators,” https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators

Anthony P. Carnevale, Ban Cheah, Martin Van Der Werf, “ROI of Liberal Arts Colleges: Value Adds Up Over Time,” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2020, https://1gyhoq479ufd3yna29x7ubjn-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/Liberal-Arts-ROI.pdf

Margot Locker, Lynn Barendsen, and Wendy Fischman, The Funnel Effect, https://search.issuelab.org/resource/the-funnel-effect-how-elite-college-culture-narrows-students-perceptions-of-post-collegiate-career-opportunities.html.

Colleen Flaherty, “New Analysis of Ph.D. Debt, Job Placement,” Inside Higher Ed, Sept. 27, 2022, https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2022/09/27/new-analysis-phd-debt-job-placements.

Stephen D. Allison and Tyrus Miller (a scientist and a humanist), “Why science needs the humanities to solve climate change,” The Conversation, August 1, 2019, https://theconversation.com/why-science-needs-the-humanities-to-solve-climate-change-113832.

Valerie Strauss, “Why We Still Need to Study the Humanities in a STEM World,” Washington Post Oct 18, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/10/18/why-we-still-need-to-study-the-humanities-in-a-stem-world/.

James Anderson, personal communication, December 12, 2021.

Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

Sarah Fullerton, “Defying negative stereotypes, humanities majors are booming at Berkeley,” Berkeley News, October 31, 2022, https://news.berkeley.edu/2022/10/31/defying-negative-stereotypes-humanities-majors-are-booming-at-berkeley/