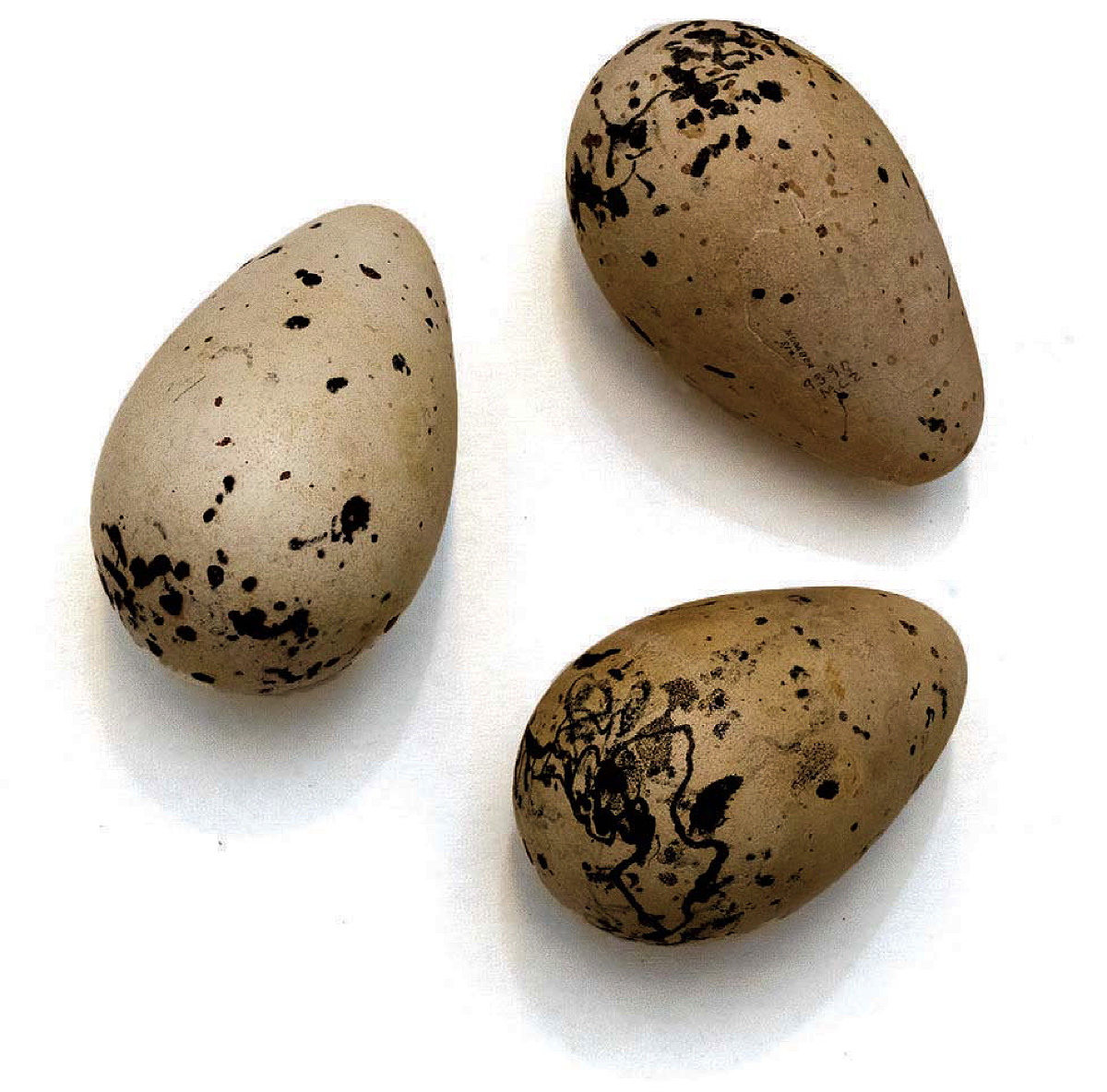

Glossy shells of the Tinamidae in Easter egg bluish-aqua hues; the fluffy indulgence of a feathered Brant’s nest; great auk shells with their conical end (maybe to keep them rolling around in a circle, rather than away from the bare-rock nesting site) and avant-garde brown splatters and splotches, like veneers of terrazzo (each perhaps a sort of QR code to help the prospective parents find their own in a dense colony).

These highlights of nature exist not precariously on the ground or along rocky shores, but safely underground, along Oxford Street. Beneath the courtyard connecting the newish Northwest Laboratory with the venerable Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard’s holdings of perhaps 40,000 egg and nest specimens are shelved in maroon (okay, crimson) metal cabinets, in the care of Jeremiah Trimble, A.L.M. ’18, curatorial associate in ornithology. A lifelong birder with the ruddy complexion to match, he came to the MCZ in 2000 and, having found the perfect roosting spot, never left.

Feathered Brant's nest

Photograph by Jim Harrison

For mating purposes, birds feature extravagant feathers and coloration. For survival purposes, their eggs are often far less showy: the more easily a predator finds something to eat, the greater the evolutionary cost. Nonetheless, there are plentiful reminders that among birds’ enchantments—their appearance, flight, song, the mysteries of migration—is the art of nidification: the 10-dollar word for nest-building.

Glossy Tinamidae shells

Photograph by Jim Harrison

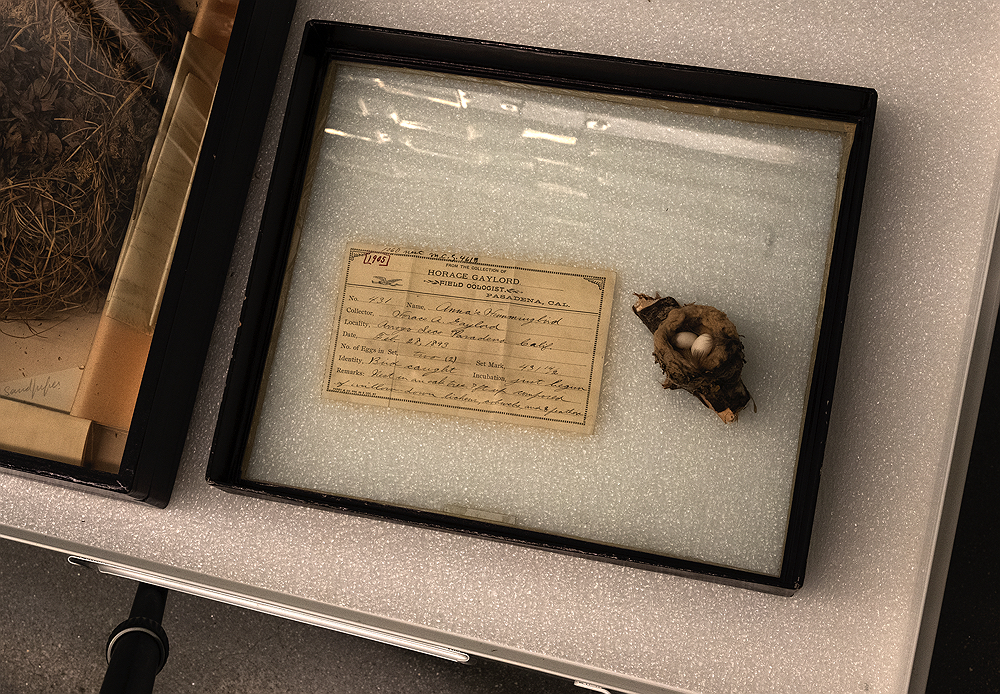

Many of the items arrived as gifts from collectors William Brewster, A.M. 1889, and John Thayer, A.B. 1885, A.M. 1910, and are accompanied by handwritten “egg cards,” elaborate vouchers from vendors who did much of the fieldwork. Contemporary scientists now use that information to help chart the advance of invasive plants (in nest material) and the ebb and flow of habitats. Accipitridae shells document the before-and-after effect of DDT: shells thinned, reproduction failed, and then recovery began as the insecticide was phased out. Because collectors drilled holes in shells to empty them for preservation, genetic researchers today can use those points of entry to harvest remnant DNA for their studies.

Conical great auk shells

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Other specimens speak for themselves. Trimble pulls out a Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus) shell identified by collector John James Audubon: “Noddy, Tortugas, May 12th 1832.” Sadly, a passenger pigeon shell and a section of a cypress log that contains an ivory-billed woodpecker nesting cavity are silent evidence of birds now extinct.

One of Trimble’s favorite drawers is filled with tiny hummingbird nests. Most passerines build where branches fork or in the crotch of a tree for stability. But many hummingbirds, he says with admiration, assemble theirs atop branches, even on clotheslines, holding the constructions together and anchoring them with sticky filaments of spider webs: the perfect building material for such delicate creatures.

Brown Noddy shell identified by collector John James Audubon

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Display of birds and collection cabinets (for nests and eggs) below

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Hand-written identification card for Anna’s hummingbird nest with eggs collected in 1893 by Horace Gaylord in Pasadena California

Photograph by Jim Harrison