Editor’s note: Amid rising concerns about economic inequality, climate change, and riven politics, the role of capitalist enterprise has come into question—at least when defined solely in terms of maximizing profitability. Even such modest notions as investment guided by environmental, social, and governance criteria (ESG) prompt fierce politicking about purportedly “woke” businesses. Geoffrey Jones, Isidor Straus professor of business history at Harvard Business School, has put both the longer-term issues and the current discourse in productive perspective in his new book, Deeply Responsible Business: A Global History of Values-Driven Leadership (Harvard University Press). This essay is adapted from his introduction, “Profit or Purpose?”

* * *

On June 4, 1927, a crowd of 4,000 gathered for a large ceremony to inaugurate the new Harvard Business School (HBS) campus, set apart from the historical Harvard campus in Cambridge across the Charles River in Boston. This was the “roaring twenties,” a prosperous time for the United States, and the campus was financed by a $5-million gift from George W. Baker, the former president of the First National Bank of New York (today’s Citibank). The New York Stock Exchange had risen 20 percent per annum since 1922, and concentration of wealth was approaching a level not seen again until the 2000s.

The dean, Wallace B. Donham, gave a short address that was more of a warning than a celebration. Scientific advances had opened up “new opportunities for happiness,” he observed, but these would not be secured without “a higher degree of responsibility.” Business leaders, he went on, needed to develop “social consciousness,” accompanied by “competently equipped intelligence and wide vision.”

In a longer article published in the school’s Alumni Bulletin eight months later, Donham further clarified his vision of what he called “The Social Significance of Business”:

“Unless more of our business leaders learn to exercise their powers and responsibilities with a definitively increased sense of responsibility towards other groups in the community…our civilization may well head for one of its periods of decline….Political leadership is on the wane while national and international problems assume more vital significance. The stake of the ordinary man in the material developments of the time is large, but these material things have apparently not produced a higher degree of happiness….On all sides, complicated social, political, and international questions press for solutions, while the leaders who are competent to solve these problems are strangely missing. These conditions are transforming the world simultaneously for better and for worse. They compel a complete reappraisal of the significance of business in the scheme of things.”

The warning of a “threat to civilization,” at the height of an economic boom, might have seemed eccentric to readers at the time, but his words were prophetic. Twenty months later, the Wall Street crash would set off a massive global economic depression, with profound economic and political consequences, including the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany.

Amid the prosperous 1920s, Dean Donham did not ask businesses to donate more money to charity for the less fortunate. Rather, he called upon them to fill a perceived leadership void and assume responsibility for saving “civilization.”

Donham was not asking business leaders to donate more money to charity to help the less fortunate. Instead, he called for business to fill a perceived leadership void and assume responsibility for saving “civilization.” His admonition appears to have had limited effect. The Wall Street crash prompted some amount of self-reflection among business leaders, but there were no radical changes in business practices. And when President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal aspired to change how the American economy worked through public spending and new social policies such as the introduction of social security, it was opposed by all but a handful of the leaders of large corporations. In time, influential voices, some of them members of the HBS faculty, others farther afield in Chicago, would insist that a business’s first responsibility was to its shareholders—that it was a mistake to suggest that business leaders should seek to play a part in righting society’s wrongs. For several decades from the 1980s on, these voices became the dominant ones.

Wallace B. Donham

Photograph courtesy of HBS Archives Photograph Collection: Faculty and Staff, Baker Library, Harvard Business School (olvwork374328)

Donham was neither the first nor the last person to call for business leaders to exercise a positive social impact beyond making profits. Almost 100 years later, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, identical calls frequently arise in the context of the looming ecological crisis, societal inequalities, and faltering democracies. Dominic Barton, the global managing director of McKinsey, denounced short-term thinking by companies obsessed with quarterly reporting. “Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders,” Larry Fink, the chief executive of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, starkly declared in his annual letter to CEOs in 2018, “including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate.” In 2019, 181 chief executives from the Business Roundtable, an association of leaders of the largest U.S. corporations, signed a statement pledging to run their companies “for the benefit of all stakeholders—customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders.”

There is reason to be skeptical whether these calls for enhanced responsibility will be answered more than were Donham’s. Global business today is by and large not only relentlessly profit-seeking but also warps institutions of government and law to serve corporate interests. The opening decades of the twenty-first century saw an extraordinary series of corporate scandals in the United States and many other countries, and there is plenty of evidence of repeated ethical lapses. But an alternative movement, supported by younger entrepreneurs committed to engaging with environmental and social inequities, places purpose and social responsibility at the heart of their business model.

A wide range of critics have asserted that the problems of contemporary capitalism are systemic, and pose major threats to society, the environment, and democracy. The giant philanthropic foundations created by multi-billionaire tech entrepreneurs in the United States have been lambasted as a charade for rich business elites to dodge taxes and extend their control. Withering criticisms of contemporary capitalism have been joined by technocratic proposals to fix the entire economic system. Re-Imagining Capitalism: Building a Responsible Long-Term Model, a collection published in 2016 (the editors included Barton), made the case for introducing changes ranging from policies to reduce income and educational inequality to getting rid of quarterly reporting, building in a bigger role for long-term institutional investors like pension funds, and establishing incentives for company boards to act more like owners pursuing long-term value creation rather than short-term gains. Five years later, McArthur University Professor Rebecca Henderson argued in Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire that management needs to become more purpose-driven and to pursue stakeholder approaches. She also called for the financial system to be “rewired” to permit longer-time horizons, and for the wholesale renewal of civil society and government.

In contrast to studies that seek to rewrite the rules of the game or change individual behavior (Henderson implores individuals to eat less red meat, drive less, and become active in forcing corporations and politicians to be better citizens), I argue that the best starting point for re-imagining capitalism is to re-imagine business—and its social purpose. I have looked at the history of business leaders since the nineteenth century and around the world who have pursued a broader social purpose than simply making profits, and who saw business as a way of improving society and, even, solving the world’s problems.

This may seem hopelessly naïve. But many of these businesses were successful, though financial success was not their only metric of achievement. These stories invite us to learn from history by asking: What does a responsible business serving a social purpose really look like? What distinguishes these businesses from their competitors? What was the intent of business leaders who pursued social purpose? Is this a practical proposition? If such responsible businesses have existed in the past, why have they never become the norm? Does good business always, or ever, translate into good profits? Is business acting beyond its specific domain if it seeks to be beneficial to society? More fundamentally, does meaningful improvement on poverty or climate change only come from governments?

Purpose and Spirituality

I begin from Donham’s call for individual business leaders to have a “higher degree of responsibility,” and explore what this phrase might mean today by looking at examples from the last 200 years, when business leaders operating under radically different conditions have gone beyond narrow profit-seeking in ways that Donham envisaged. I term these endeavors “deep responsibility” to distinguish them from the superficial rhetoric of “corporate social responsibility”—a language available to any corporation that sprinkles a few good deeds on top of its not-so-good works.

Deeply responsible business leaders are motivated by a set of values that shape their practices. For some, it is the bedrock foundation of virtuous character in its leaders that prompts them to act in a fashion that promotes human flourishing, a term the management scholar John Ehrenfeld has defined as “the full realization of the human potential.” Honesty, fairness, loyalty, compassion, courage, and generosity are among the most important of these. These virtues are reinforced by practical wisdom, what Aristotle called phronesis, which enables the virtues of character to be exercised. The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre has dismissed the possibility that a manager in a for-profit business could ever be virtuous. I challenge that assumption. Meanwhile Ikujiro Nonaka and Hirotake Takeuchi’s The Wise Company argues that businesses have no place for virtue, arguing that practical wisdom alone is the key. They find such practical wisdom most often in Japanese management, but my aim is to show it can be seen in many contexts.

Milton FriedmanPhotograph from the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice/in the Public Domain

Perhaps the most influential critic of the purpose-driven business model was Milton Friedman, an influential economist at the University of Chicago and apostle of the free market, who insisted in a widely cited 1970 article, as the title proclaimed, that “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits.” The responsibility of corporate executives, he argued, was to “make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society.” Friedman’s view helped transform business leaders’ perception of their purpose and function around the world. I look at its impact, and consider the arguments and evidence, in purpose-driven businesses, of those who fundamentally disagreed.

A second type of value driving deep responsibility is spirituality. As this might evoke misleading images of unworldly saints and raise doubts about the relevance of my historical cases to the present day, I stress that my meaning is broad and holistic. Although a minority of the business leaders studied in this book held strong religious beliefs, including Christian, Jain, and Muslim, others were influenced by secular philosophies or by their own life experiences. I define spirituality broadly as an implicit or explicit belief in the interconnectedness of all life and the planet that translates into a set of guiding principles and values. Such values promote genuine moral commitment, reduce fear of unknown futures, benefit others, and encourage a holistic understanding of problems and solutions.

Three practices appear common among deeply responsible business leaders. First is the choice of an industry with some form of social value that is not actively harmful. Second is the nature of the interaction with other stakeholders, including employees, suppliers, customers, and government: deeply responsible business leaders act with purpose and humility and avoid harmful relationships with other stakeholders. Third, deeply responsible business leaders support communities: as profoundly important as community is to human society, the continuing rise of individualism and the forces of globalization have often undermined it.

Despite those forces, I have identified business leaders who should be seen as the progenitors of the socially responsible businesses of today.

Changing Perspectives on Businesses’ Social Responsibility

Well before Donham—dating back to the social reform movements inspired by the hardships that accompanied the Industrial Revolution—there is a long tradition of debate about the purpose and social responsibility of business. The view that the sole purpose of business was to maximize value for shareholders, widespread from the 1980s on, was never dominant historically. Put into historical perspective, that supposed article of faith is in fact an extreme and problematic proposition.

Businesses of one sort or another have been around for millennia, long before modern capitalism, and so have questions about corporate ethics and responsibility. The greed of merchants and financiers has been an abiding concern across all societies, offending morals so deeply that bad business behavior is a feature of comic literature across cultures and is proscribed by religious taboos. Merchants and financiers were rebuked in medieval Europe for feeling no responsibility for anything beyond their own selfish interests. “Although it is hard to imagine today,” the accounting historian Jacob Soll has written, “guilt weighed heavily on medieval bankers and merchants.” As modern industry emerged in eighteenth-century Britain, there were breathtaking examples of skullduggery and moral failure, as well as extravagant financial swindles like the South Sea Bubble of 1720. Fraud was a regular occurrence. But so was the push for greater benevolence.

Adam SmithPhotograph from the Scottish National Gallery/in the Public Domain

In The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith is widely thought to have cast aside concerns about the destructive aspects of financial speculation, suggesting that making money should occur regardless of ethical considerations, ushering in a new age of capitalism. A businessperson’s pursuit of self-interest would, in Smith’s famous phrase, work through the “invisible hand” of the market “to promote an end which was no part of his intention.” He continued, “By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intended to promote it.”

But Smith wasn’t really saying what modern readers want to believe. He excluded from this beneficial cycle of cause and effect a category of financial speculators he called “projectors” who sought “extraordinary profits.” He supported legal restrictions on interest rates for that reason and also made clear his disdain for gross inequality. “No society can surely be flourishing and happy,” he observed, “of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable.” The economic historian Emma Rothschild has made it clear that only in a later generation’s skewed reinterpretation did Smith say that unfettered market forces would yield an optimal general equilibrium.

Smith mentioned the “invisible hand” only once in The Wealth of Nations, but in the 1790 edition of his first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), he was more specific about the benefits it delivered. It led, he wrote, to “nearly the same distribution of the necessities of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants.”Thus, although that book stressed the distributional role of the invisible hand in later editions, the original volume featured an actor called the “Impartial Spectator”—an imaginary figure who might be equated with the conscience, within each person, that encouraged an interest in the fortunes and happiness of others. The Impartial Spectator provided an ethical framework within which capitalist markets could best function. The character nurtured the virtues—temperance, justice, prudence, courage, benevolence, love—that Smith saw as essential to building “flourishing” societies. This emphasis on the importance of virtue placed him in a philosophical tradition extending back to Aristotle.

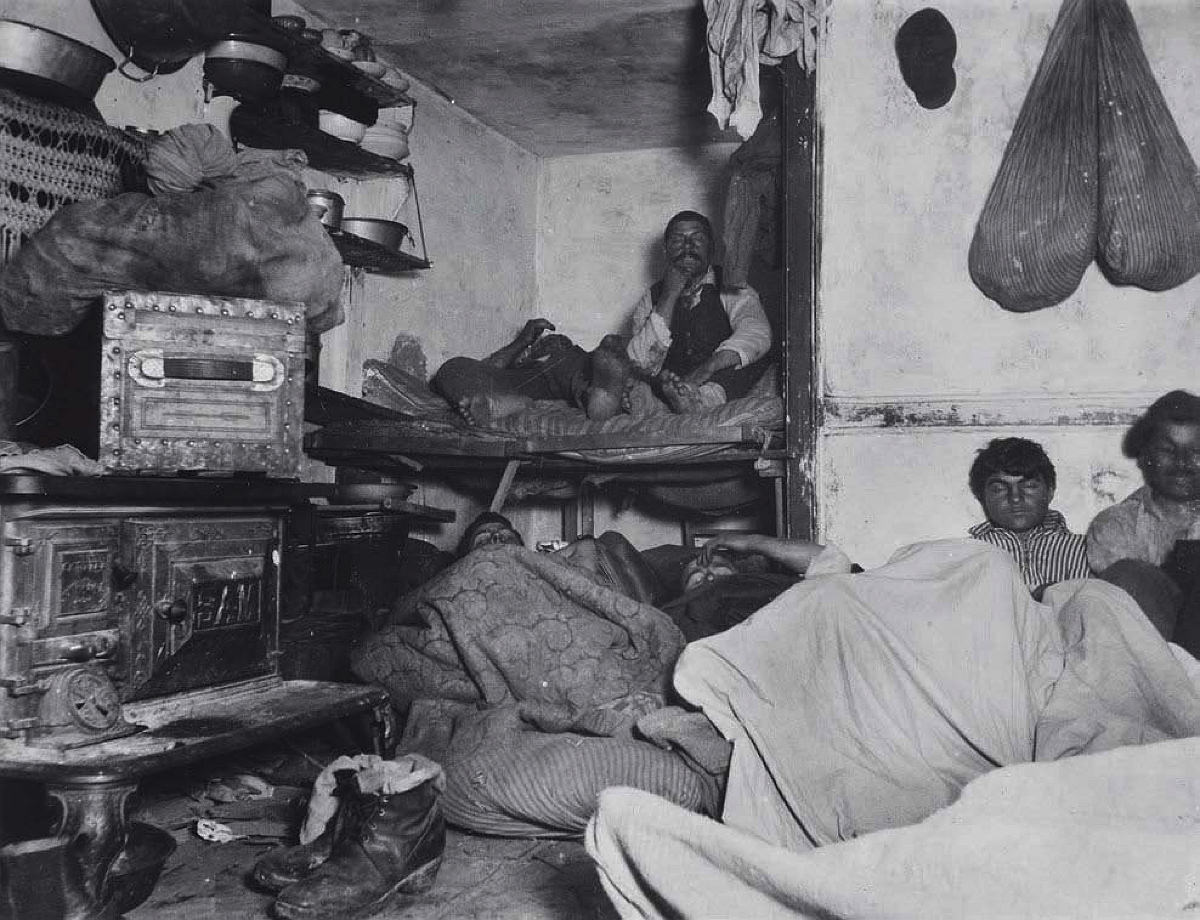

Wealth soared as the West industrialized, but workers toiled and lived in squalid conditions: Magnolia Cotton Mills, Mississippi, 1911

Photograph by Lewis Hine/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Bayard Street Tenement, New York City, 1889Photograph by Jacob Riis/in the Public Domain

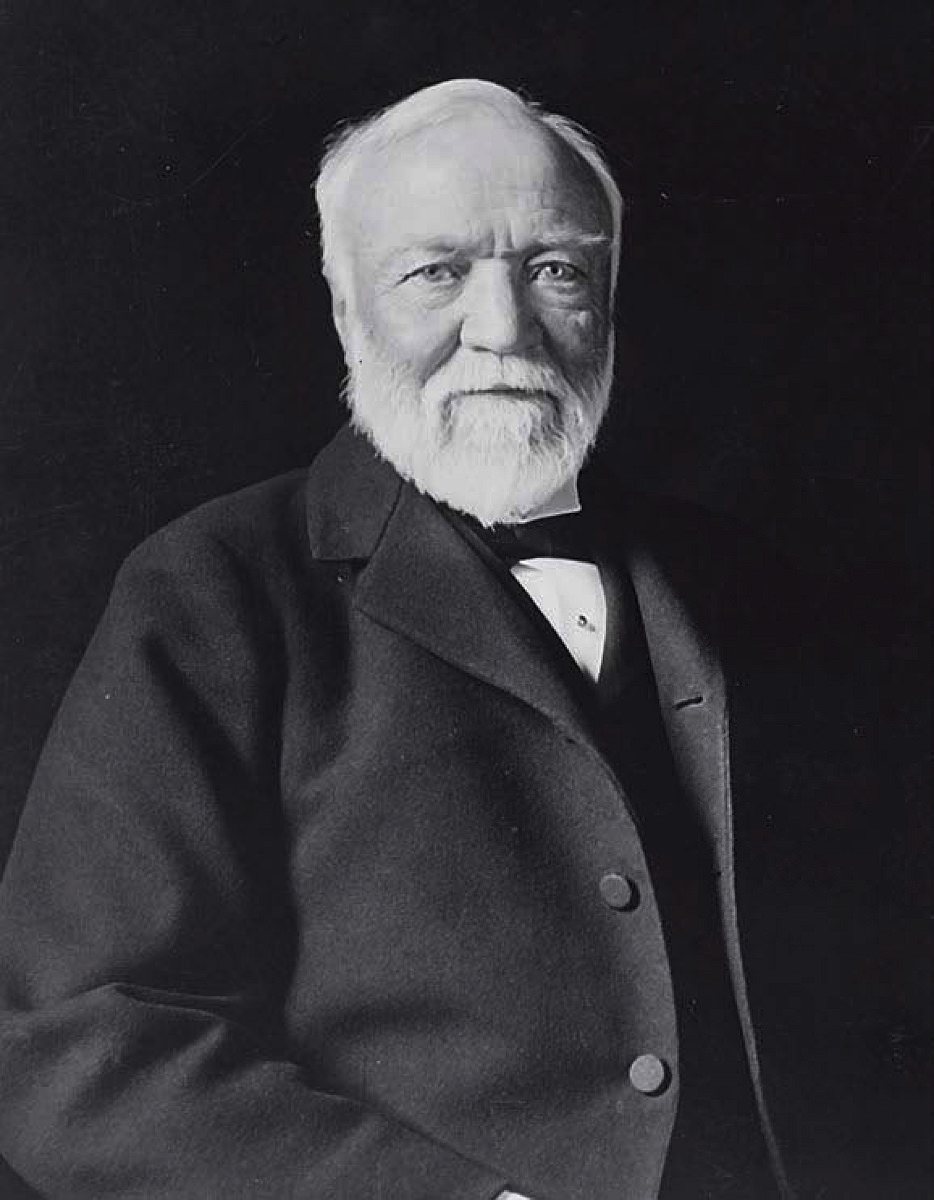

Future generations echoed the apocryphal father of capitalism’s belief that business had a responsibility to operate within an ethical framework, although there were many different perspectives on the forms of such responsibilities and the structure of the ethical frameworks. As modern industry transformed the world, wealth soared in the industrializing West during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—but with gross inequalities as the owners of capital grew rich while urban factory workers lived and worked in squalid conditions with little or no social protection. A mixture of ethical considerations and self-interest encouraged some large employers to provide welfare benefits for their workforces. Others used their new wealth to engage in philanthropy. Among the most radical proponents of philanthropy was Andrew Carnegie, who became hugely wealthy building a steel business in the United States. In an essay entitled “The Gospel of Wealth” (1889), Carnegie argued that business leaders had a responsibility to use their wealth to promote social good. True to his word, he gave away almost all of his personal fortune of $145 million (around $10 billion in 2022 dollars) to establish the Carnegie Foundation, whose mission was “to promote the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding.”

Andrew CarnegiePhotograph by Theodore Marceau/in the Public Domain

Meanwhile, another stark wealth gap cropped up between the industrial nations of the West and most of the rest of the world, which lagged in developing modern industries and became—often under Western colonial tutelage—suppliers of commodities and food to the affluent West.

Early pioneers. Even as early industrialization gathered force, leaders of large businesses in Britain, the United States, and Germany responded to the central challenge of inequality that arose in this era. George Cadbury, Edward Filene, and Robert Bosch addressed different aspects of this broad challenge and proposed different solutions. (See sidebar, below.) But they shared a commitment to radical ideas about the social responsibility of business and a willingness to execute on those ideas. They held a common commitment to ethical behavior and cared deeply about the welfare of their employees. Crucially, they also recognized the limits to what could be achieved by a single business enterprise and shared a belief that their responsibility extended beyond the borders of their firms. Their contemporary Shibusawa Eiichi shared these qualities and beliefs, though he was born into a country (Japan) that had not taken part in the first wave of industrialization. As a result, he pursued a vision of business contributing to a more affluent as well as more equitable future for his society.

From left: George Cadbury, Edward Filene, and Robert Bosch

From left: photograph in the Public Domain; courtesy of the Library of Congress; photograph in the Public Domain

Business Innovators in Brief

In 1861, George Cadbury and his brother Richard took over the small business that had been founded by their father in Birmingham, England, and turned it into that country’s largest chocolate manufacturer. A devoted Quaker, George sought to promote a fairer society. He invested extensively in the welfare of his employees, including building a garden village for them (and others), which he donated to a charitable trust. Beyond his firm, he was a huge philanthropist, and an influential campaigner for old-age pensions and other social reforms.

Edward Filene and his brother Lincoln transformed a small family retailing business in Boston into Filene’s, one of the largest mass retail companies in late nineteenth century United States. Appalled by the concentration of power and wealth, he developed ambitious welfare programs, and even attempted (unsuccessfully) to transfer ownership to his employees. Forced out of his own firm, he drove the spread of credit unions in the interwar years, and founded an institute to combat nativism, anti-Semitism, and misinformation.

Robert Bosch created his eponymous engineering company in late nineteenth-century Germany. He developed an advanced welfare program for his employees—whom he always called associates—with an emphasis on their freedom and choice. His extensive philanthropy focused on promoting education and alternative medicine. Bosch’s company provided cover for the German resistance to the Nazi regime during the 1930s, though its production was a major contributor to the German war machine.

In Adam Smith’s time, thousands of small family-owned firms competed mostly in their local markets, but by the first half of the twentieth century, some American and European businesses had become huge corporations that spanned the globe, dominating new industries such as automobiles and oil. Although family ownership remained important, a growing separation of ownership and control precipitated calls for the professional managers of large corporations to address perceived societal ills. These trends took place in the context of major political and economic shocks that reverberated around the world: two world wars, the Great Depression, the Cold War, and decolonization.

Global businesses and colonial independence. The growth of big business occasioned debates about the societal responsibilities, if any, of these very large organizations. With the rise of the first business schools, those debates prompted interwar endeavors to incorporate social and ethical responsibility into the education of the next generation of professional managers of large corporations—including the efforts of HBS dean Wallace Donham and the perspectives of philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, who wanted the leaders of large corporations “to think greatly” about their role in society. In the postcolonial era, other issues concerning the responsibility of business leaders arose; during the interwar struggle for independence in India and the subsequent building of a new nation, for example, Mohandas Gandhi held well-developed views concerning the responsibilities of business to all stakeholders, as well as a belief that it was its obligation to uphold the highest ethical standards. Leaders like Kasturbhai Lalbhai, who built a profitable textile manufacturing business while supporting the independence struggle, operated it to high ethical standards and navigated the new complexities of independent India in a restrained fashion.

Balancing private and public good. Even before the end of World War II, the view that business leaders had a social responsibility was becoming formalized. In interwar Britain, Quaker business families associated in particular with Benjamin Seebohn Rowntree had already become prominent proponents of the view that business should subordinate private gain to public good. Rowntree and his associates published influential books on the responsibilities of business. Oliver Sheldon’s The Philosophy of Management (1923) was especially wide-ranging. The third chapter, “The Social Responsibility of Management,” maintained that the output of industry needed to be assessed by a “double valuation” of “ethical” as well as “economic” standards.

In the wake of the Allies’ victory in World War II, when Americans wished to make capitalism as attractive as possible to offset Soviet propaganda in the Cold War, such ideas moved into the mainstream. Howard Bowen’s The Social Responsibilities of the Businessman (1953) is regularly credited with devising the term “corporate social responsibility.”

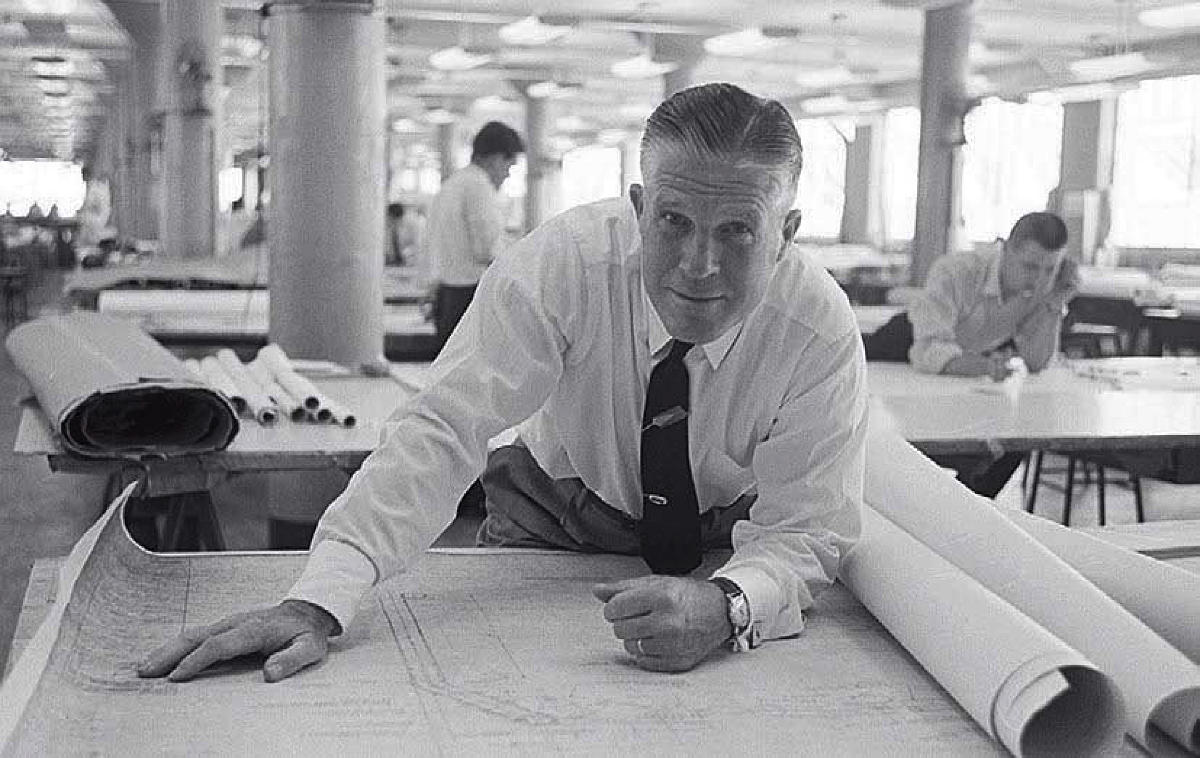

George RomneyPhotograph from Alamy Stock Photo

George RomneyPhotograph from Alamy Stock Photo

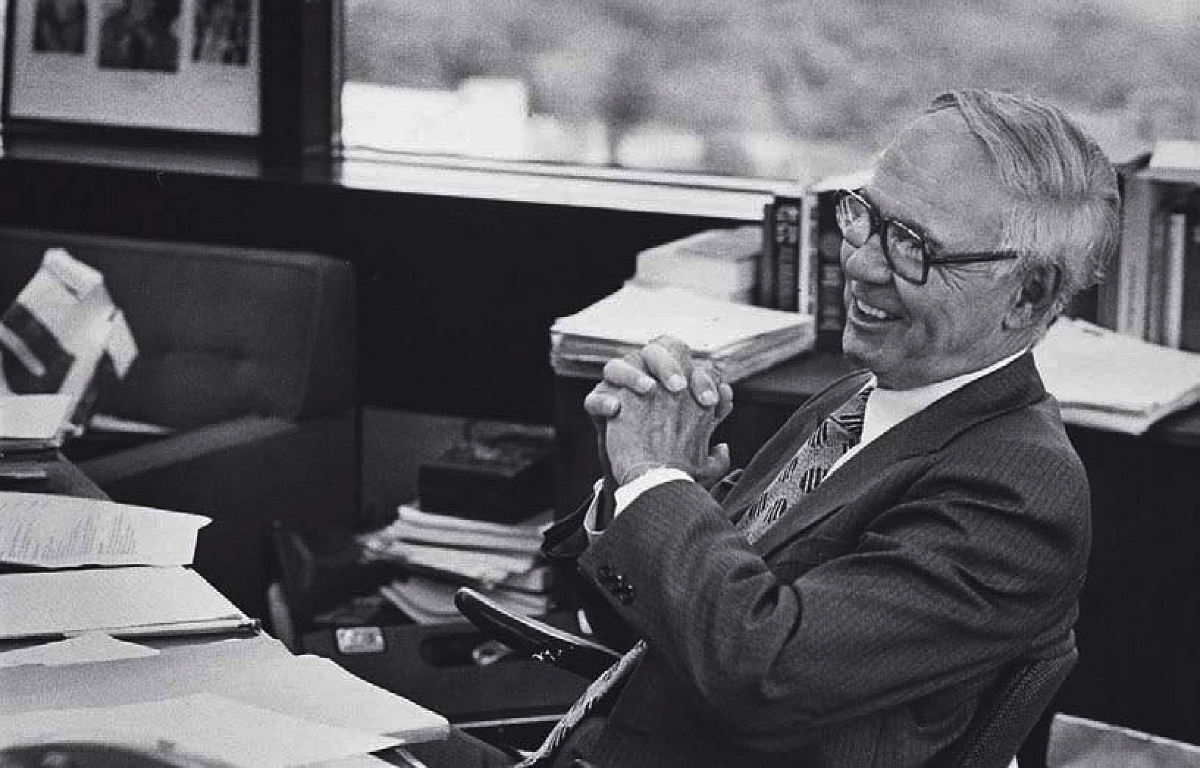

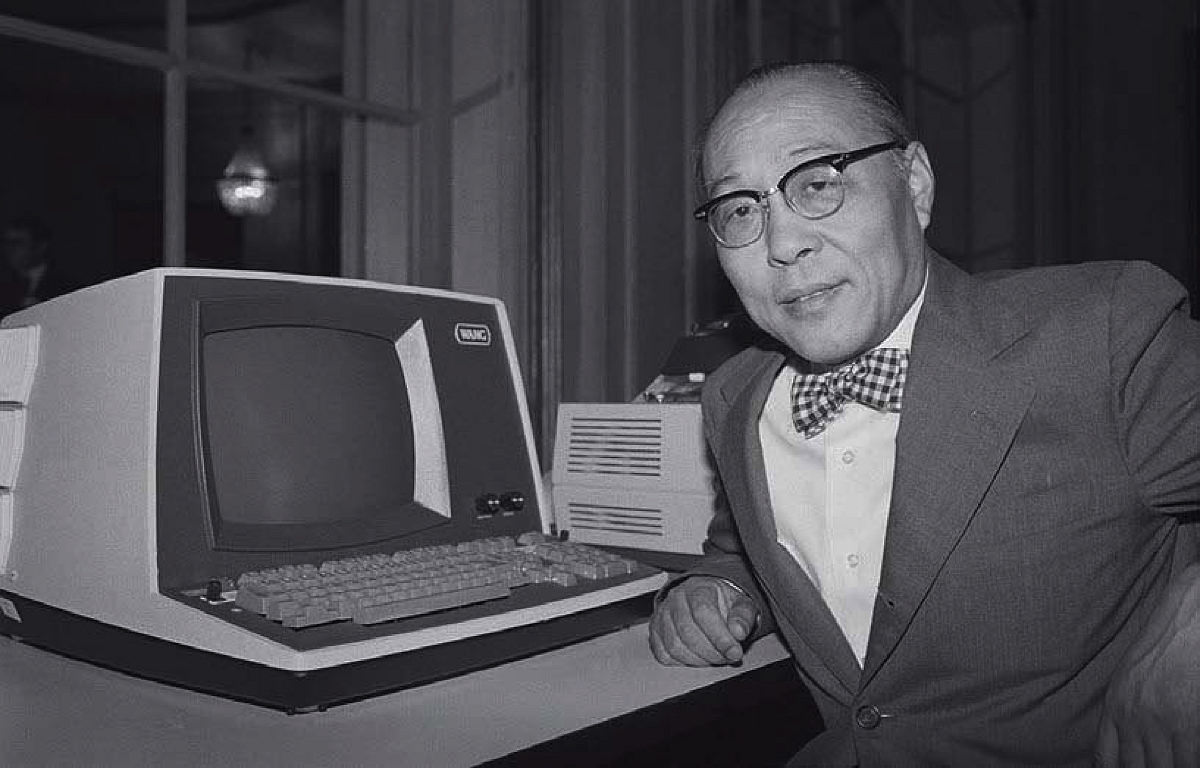

An WangPhotograph from the Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

An WangPhotograph from the Bettmann Collection/Getty ImagesThe view that large corporations should be socially responsible was the norm among United States business leaders then—although there were considerable disagreements as to what this actually meant. For example, automobile manufacturer George Romney pursued strategies to combat wasteful consumerism by promoting the compact car, and computer pioneers William C. Norris and An Wang used their businesses to provide employment and other opportunities to people from impoverished urban neighborhoods.

Shareholder capitalism and social responsibility. Of course, those businesses stand out in an era of shareholder-focused capitalism. Milton Friedman’s skepticism about the social responsibility of business did not operate in a vacuum; he was a prominent figure in the “Chicago school” of free market economists who made the case for laissez-faire capitalism, extolling the virtues of unfettered markets with minimal government intervention. Two economists working in this tradition, Michael Jensen and William Meckling, developed “agency theory”: the idea that shareholders were principals who hired executives as their agents, whose purpose was simply to maximize financial returns for their principals. Executives were to be incentivized by stock options, focusing their attention on share prices and stock buybacks (dominant traits of executive compensation plans and corporate finance today). As the assumption that the purpose of business is to maximize shareholder value spread widely, accompanying broad shifts in the political economy magnified the effect, as from the 1980s many governments liberalized and deregulated their economies, perceiving the market rather than public policy as the most efficient means of wealth creation.

Nonetheless, some business leaders sought alternative paradigms to shareholder value and agency theory, instead stressing their firms’ broader social responsibilities. A cohort of self-identified values-driven businesses that flourished during the 1970s and 1980s reflected the new belief that markets were better placed than governments to solve societal ills, but disagreed profoundly with the view that the purpose of business was to maximize shareholder value. Instead, the founders of businesses like Patagonia, Ben & Jerry’s, and The Body Shop believed that a for-profit business could be a vehicle to achieve a more just and sustainable world.

There is a continuous narrative of social responsibility embedded in the past few centuries of increasingly prevalent—and of late, increasingly shareholder-focused—capitalist enterprise.

Building and Sustaining Responsible Enterprises

As my historical inquiries demonstrated, there is a continuous narrative of social responsibility embedded in the past few centuries of increasingly prevalent—and of late, increasingly shareholder-focused—capitalist enterprise. Alongside those encouraging examples is another narrative: the reliance on founders or charismatic individual business leaders to ground a vision and practice of deep responsibility in their organizations. This often raised the challenge of sustainability once that individual retired or otherwise left a firm, or if the firm sought access to finance from outside investors or the capital market.

The historical record again informs strategies to build systems and institutions in which individual, deeply responsible business leaders and their firms could find validation and support. The oldest endeavor to build such a system was among a set of businesses founded since the 1920s under the influence of Rudolph Steiner’s Anthroposophy (an early twentieth-century philosophical movement that argued that humans operated both on earth and in the spiritual world). This movement experienced renewed growth from the 1980s, playing a formative role in emergent sectors such as organic food and sustainable finance. Here we will look especially at an Egyptian biodynamic food business created by Ibrahim Abouleish and a biodynamic tea business in Darjeeling, India, developed by Sanjay Bansal.

More recent efforts to institutionalize deep business responsibility focus on defining, measuring, and benchmarking it, and developing communities with its values: ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investing pioneered by Joan Bavaria and others; the B Lab Movement and especially its important Latin American outgrowth, Sistema B, the Economy of Communion (an outgrowth of Catholic social teaching); and the recent momentum behind diffusing and supporting the steward-ownership model (in which a company is “self-owned” and managed by stewards who have exclusive voting rights, but no economic rights in the company).

Throughout, the history of private business enterprise yields concrete examples of deeply responsible business leaders operating at different times and in different contexts. None is the template for how to re-imagine a complex system such as capitalism. Rather, they show how individual efforts to pursue what Wallace Donham called “an increased sense of responsibility” have succeeded and failed, and why. Deeply responsible business leaders are regular human beings with all the foibles of people in general. Some are inspirational, but some of their experiments in social purpose were not successful or sustainable. In some cases, virtue signaling was not borne out by virtuous practices.

The record of such businesses punctures facile assumptions that doing good will necessarily be good business. Pursuing profits and purpose is never easy, and sometimes the two goals are in conflict. But of great importance, especially at this time of economic, environmental, and social challenge, the record clearly shows that throughout the history of capitalism, deep responsibility is not an idealistic fantasy, but rather an essential path for the future.