“We are not the exception to the norm—we are actually the norm,” said formerly incarcerated artist Jesse Krimes during a panel discussion at the Harvard Art Museums March 22 that followed the screening of a documentary about his life and work. “There are so many just incredibly talented people that we lock away in cells for decades.”

The event, which probed mass incarceration, racism in the justice system, and art as a tool for survival, was co-sponsored by the Institute to End Mass Incarceration (IEMI), based at Harvard Law School, and the journal Inquest, founded in 2021 and published by IEMI as “a forum for advancing bold ideas to end mass incarceration.” The discussion was moderated by Menschel curator of photography Makeda Best and Law School lecturer Premal Dharia, who is executive director of IEMI and founding editor of Inquest.

The moderators and panelists from the Harvard Art Museums discussion: (from left) Makeda Best, Premal Dharia, Jesse Krimes, and Russell Craig

Photograph by Lydialyle Gibson/Harvard Magazine

Released last September, Art & Krimes by Krimes chronicles the journey of a troubled teen and gifted artist who grew up in eastern Pennsylvania, the son of a teenage mother and a beloved stepfather who died in a drug-related suicide. “It was no secret that I was a train wreck,” Krimes says early in the film. By the time he was 13, he’d started selling marijuana and then cocaine, and he began getting arrested; for years he was in and out of jail and juvenile probation. In 2009, a year after graduating from Millersville University with a degree in art, he was sent to federal prison for six years on drug charges: cocaine possession with intent to distribute.

In the film, Krimes recalls that the judge who sentenced him told him that he’d just given 20 years to another defendant, who had a similar criminal history and was convicted of the exact same offense. “But I see value in you,” Krimes remembers the judge saying. Krimes realized that the other defendant was the man he’d been sharing a holding cell with earlier that day. “And it was a black guy.” Krimes is white. Race, he felt, had been the strongest deciding factor. That theme—racial bias and inequality—kept resurfacing in the film, and also in the discussion at Harvard. Krimes described the obligation he feels to empower and promote formerly imprisoned artists of color, and he talked about noticing, as his career began to blossom, that in exhibitions about mass incarceration, he was often the only artist whose work was shown. “And as a white man, that is not reflective of the carceral state and who it predominantly impacts,” he said. “And so there was no way I was going to make a film that didn’t actually talk about the reality of the situation.”

Jesse Krimes sits in front of “Apokaluptein:16389067,” the 40-foot cloth-panel mural he created while in prison. Still from the documentary Art & Krimes by Krimes.

Behind bars, art became his escape. Krimes studied philosophical texts—Agamben’s The Kingdom and the Glory, Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth—and developed new artistic techniques, foraging for whatever creative supplies he could find. He made a series of small portraits using newspaper mug shot images, playing cards, and thin slices of soap. His monumental opus, which took three years to produce, was a 40-foot mural made from prison-issue bedsheets, plastic spoons, New York Times clippings, and hair gel from the commissary. Because the artwork itself was contraband, Krimes had to smuggle it out by mail, piece by piece. “It was almost like sending out pieces of myself out of the prison walls,” he says in the film. After his release, he was able to assemble the bedsheets into a whole for the first time: a colorful meditation on heaven, hell, sin, redemption, and purgatory. He titled the work “Apokaluptein:16389067,” after the Greek origin word for apocalypse (which means “uncover” or “reveal”) and his prison identification number.

The documentary follows Krimes for the first five years after his release, chronicling his struggle to reintegrate himself into society and family life, and to gain a foothold—and a career—in the art world. (His work is now in the permanent collections of several galleries and museums, including the Brooklyn Museum; and it has been exhibited at venues including MoMA PS1, Palais de Tokyo, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.) Along the way, the film introduces other formerly incarcerated artists—all of them black men—including Russell Craig, whom Krimes met when they both were recently out of prison and working together for the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, a nonprofit that creates and maintains public murals in the city. In 2017, Krimes and Craig co-founded Right of Return USA, which offers $20,000 fellowships each year to half a dozen formerly incarcerated artists (alumni have gone on to receive a MacArthur Fellowship, the Pulitzer Prize, and Guggenheim fellowships, among other awards). The two men recently received $1.1 million from the Mellon Foundation to help expand their fellowship program into a nonprofit called the Art and Advocacy Society, which will include a school and residency program.

During last week’s discussion, Krimes and Craig spoke about their ambitions for the expanded organization, the shifts in their own artistic practices, and the sense of responsibility they feel toward other formerly imprisoned artists. “It’s beyond yourself,” Craig said, in response to a question from Best about how launching the Right of Return fellowship had changed his own artwork. “It’s like, people are really there with you, when you thought it was just you in the studio.” Previously, he was used to situations where “You just make the work for you, and whatever issue I wanted to bring to light. But then when you inspire people that you didn’t know you were inspiring”—the fellows, who are also struggling to make their way as artists—“all that just adds an extra layer of how serious it is, and how much it is beyond you.” A painter and muralist, Craig combines historical and pop-culture references to create large-scale portraits that comment on the brokenness and violence of mass incarceration.

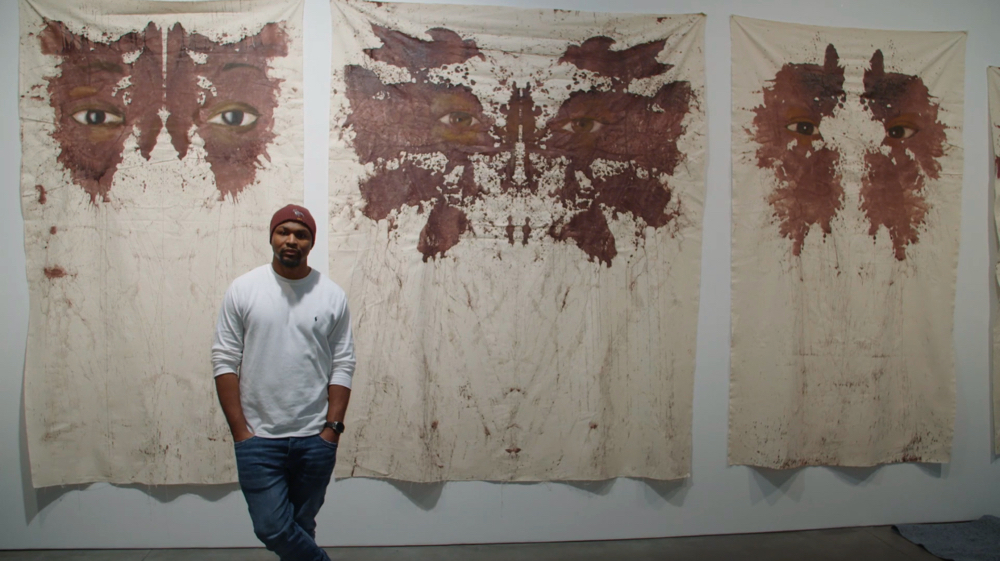

Artist Russell Craig with paintings from his Eval series, in which he uses ox blood and paint to create Rorscach-like portraits of women killed by police. Still from the documentary Art & Krimes by Krimes.

Courtesy of MTV Documentary Films

Krimes noted the “decades of artistic community” that the organization’s fellows were denied during their time in prison. Many also are technically gifted and accomplished but lack other necessary skills: they don’t know how to write an artist statement, or apply for grants, or set up a website. And “they’re entering into a world and society that puts up a lot of barriers to access.” Even ordinary artists struggle, he said. “But an artist who has come from the experience of incarceration, you’re starting multiple decades behind everybody else.” These factors were partly what prompted Krimes and Craig to think of expanding the Right of Return fellowship into a more all-encompassing program, with instructional resources and a residency that would allow space and time for uninterrupted work. “Because, people are making very strong works,” Krimes said, “but they also need that criticality and feedback from a community of artists to really sharpen them, to help them understand, ‘Well, why are we making this? What does this mean?’”

Having had that kind of formal, critical attention to his artwork before he went to prison was partly what saved him, Krimes said, and then helped propel his rise in the art world once he was released. “I was lucky—like, I went to school,” he said. “From the age of 13, I transitioned through nearly every facet of our criminal justice system….But there was a moment when I got to go to school, and I had amazing professors who really challenged me. And so it was a no-brainer when I went into the system” to immerse himself in art. “But I came across all these guys who were making such incredible work....And it’s coming from this very deep place of genuine creativity.” Most of the artists Krimes met in prison, and the formerly incarcerated fellows he and Craig work with now, are self-taught. Krimes tries to engage with them “the same way my professors pushed me and challenged me,” he said. “It just takes someone who actually [cares] and says, ‘Have you thought about this? Your work is touching on these things; you should read this book. Maybe you should look at this artist.’ You know, it doesn't take much—it just takes a little bit of genuine care and kindess and interest. And people will create masterpieces.”