At age 54, as a successful standup comedian with movie and national TV experience, Jimmy Tingle did something that hardly any of his comedic colleagues would have opted for—or even, well, entertained. In 2009, Tingle, M.P.A. ’10, applied to Harvard Kennedy School (HKS). “I’d performed at lots of fundraisers for nonprofit, social, and political causes,” he recalls, “but I wanted to use my skills as an entertainer for purposes beyond entertainment. I even thought I might go into public service.”

At his commencement, Tingle delivered the Graduate English Address, capping the experience of earning a graduate degree in his sixth decade. “It was a great education that nurtured and recharged me,” he says. “Plus, you have the best of both worlds—a student ID and a senior discount.”

In 2018, Tingle ran as a Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor of Massachusetts. His HKS degree “helped give me the level of credibility one needs as a candidate for public office,” he explains. Years earlier, he had made a satirical run for U.S. president and learned routine political behaviors: “I’d go into the audience, kiss babies, shake hands, and ask for money.” Performing at 2016 fundraisers for Hillary Clinton, he met Barney Frank ’61, J.D. ’77, the former longtime U.S. congressman from Massachusetts. Frank encouraged Tingle to stand for election, adding that lieutenant governor was the perfect office for him, and volunteered to be honorary chair of his campaign.

When Tingle met with friends and family to announce his candidacy, he informed them that state law limited campaign contributions to $1,000, eliciting chuckles and a consensual response of, “No problem there.” He put a comic twist on his campaign issues. Regarding immigration: “Sneaking into the country to work is sort of like breaking into a house in order to clean it!” On arming teachers: “My brother is a teacher. It’s a stressful job. Don’t give him a gun!” For renewable energy, he spun out an alternative to offshore wind farms: placing turbines alongside the Massachusetts Turnpike to capture the wind generated by thousands of cars whooshing by. (Ironically, years later, a message from India arrived, complete with video, noting that his vision had become a reality there.)

Tingle’s campaign even enlisted Hollywood star Matt Damon ’92 for a Facebook ad. In the end, he drew 213,000 votes, 41 percent of those cast and good enough, Tingle notes, for second place. “The bad news,” he adds, “is that it was a two-person race.” (The winner, lawyer and former Obama aide Quentin Palfrey ’96, J.D. ’02, lost in the general election to Republican Karyn Polito.)

Born in Cambridge, Tingle went to public schools and was an altar boy. “Dad owned and drove taxis,” he remembers. “The family car was a cab. One time he even took us hunting in a cab.” He studied history at Southeastern Massachusetts University, graduating in 1977. As a boy, he’d enjoyed TV sitcoms like The Beverly Hillbillies and in college discovered Saturday Night Live and saw the 1974 Bob Fosse film, Lenny, on Lenny Bruce. “There was a more serious theme to the comedy coming out of the ’60s,” Tingle says, “on issues like the Vietnam War and civil rights.”

In 1979, the Ding Ho Chinese restaurant in Cambridge’s Inman Square created what became a legendary venue for standup comedy only two blocks from where Tingle grew up. Many entertainers began there, including Steven Wright and Paula Poundstone. In 1980, Tingle got an open-mic slot. Forty friends turned out and gave a “really strong reception” to his act, which included song parodies like the “Test-Tube Baby Blues.” Tingle started working at the Ding Ho for $3 an hour plus all he could eat and drink. “I was a doorman, bartender, janitor. I picked up supplies and groceries,” he recalls. “I was there all the time.” He also did a weekly standup set, and played open-mic nights at Boston-area comedy clubs, which were sprouting up amid the standup boom of the 1980s. He even did street performing in Harvard Square. “Once I started performing at open-mic nights and got the audience to react and laugh at my ideas,” he says, “I was hooked.”

Tingle compares creating comic material to writing a song, poem, or article: “You take a personal experience, observation, or insight and share it with an audience of total strangers who can understand and, ideally, laugh at it. Very rarely does the artist get it 100 percent right on the first draft. It takes time to hone a routine by repeatedly performing the piece, recording yourself, listening to it, editing the piece, and repeating the process until you have total confidence in the material.”

One recent joke of Tingle’s pokes at cultural ideas—and biases—regarding what counts as law and order: “Joe Biden hired 100,000 police officers, and the top 1 percent said ‘Good, they’re going to catch criminals.’ Then he hired 87,000 IRS agents. The same people said, ‘Bad—they’re going to catch us.’” In another joke, he connects a friend’s obstinacy with a broader social issue. “A friend of mine is a recovering heroin addict. During the pandemic he refused to take the COVID vaccine. I said, ‘Why won’t you take the vaccine?’ His exact words were ‘You don’t know what’s in it!’ I said, ‘You’ve been buying illegal drugs on the streets from strangers. What do you think? They were approved by the surgeon general?’”

The 1980s were also a saturnalian era—“I lost friends to alcohol and drugs,” he recalls. Tingle struggled with alcohol, too, and at Christmastime 1987, called Cambridge Hospital asking for help. The staffer who picked up the phone replied, “You called the right place.” Grateful and relieved, Tingle spent seven inpatient days detoxing. That week was a turning point for him, and those five reassuring words became his touchstone for how society ought to treat people in trouble.

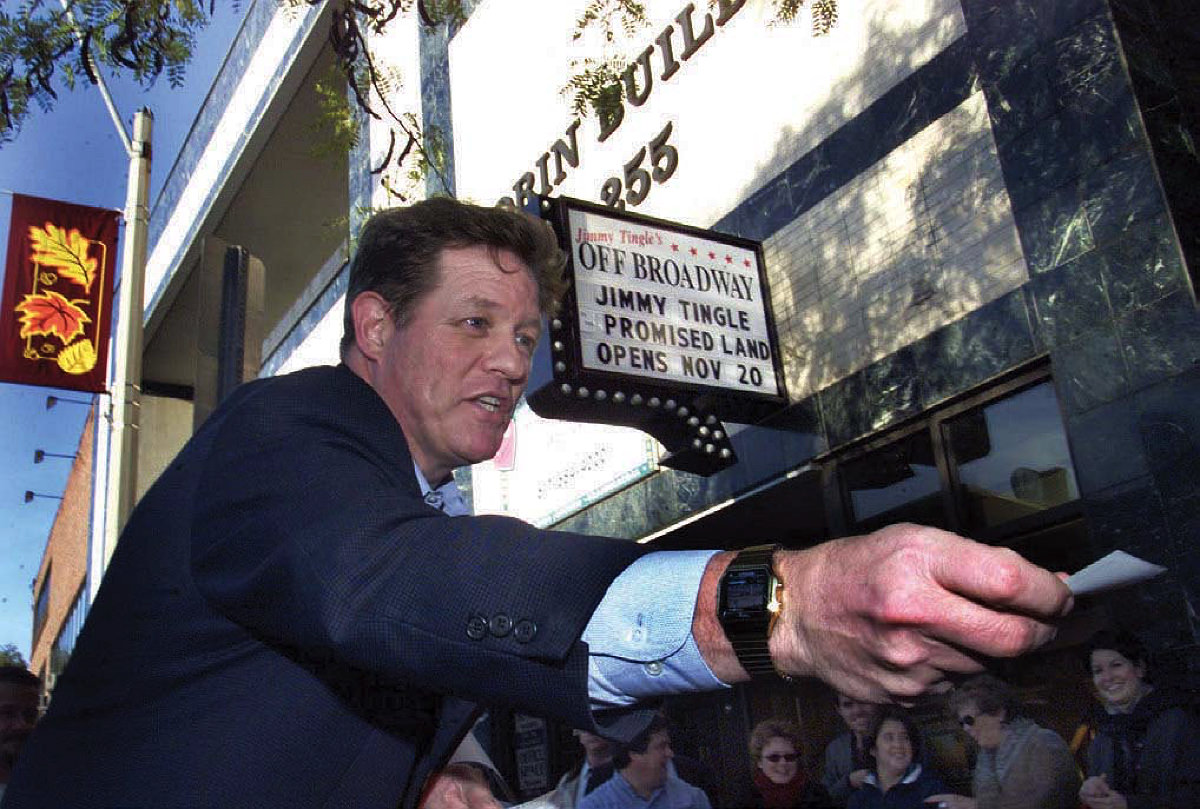

Tingle hands out tickets in 2002 to his OFF BROADWAY Theater in Somerville.

Photograph by Wendy Maeda Boston Globe/Getty Images

With sobriety, his career zoomed. In 1988 he moved to New York City and appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Seeing comic Jackie Mason’s one-man show led Tingle—who’d only ever played comedy clubs—to open his own solo show in theaters in New York, Los Angeles, and at the Hasty Pudding Theater in Cambridge. He made regular appearances on MSNBC and 60 Minutes II, mixing humor with news commentary. Between 2002 and 2007, Jimmy Tingle’s OFF BROADWAY Theater in Somerville staged performances of all types.

Today he lives with his wife, photographer Catherine McDermott-Tingle, in Cambridge, where they raised their son, Seamus. Tingle is producing a film on his run for lieutenant governor. In 2010 he founded Humor for Humanity, which provides his entertainment and fundraising expertise to nonprofits and social causes.

Tingle also continues to perform. His material puts him in a politically charged domain: while conveying his own values, he has to respect his audience, without pandering. “With political humor, if the audience doesn’t know you, one word can divide them, instantly,” he says. “A word like Trump, Obama, Biden, or Hillary, for example. If you want to build a better, more tolerant society, you will avoid stereotypes. That’s your North Star.”