Seven hundred people were surrounded by taxidermied peacocks and monkeys in the lounge of New York’s Jane Hotel. That evening this spring, they gathered beneath the erratic light of a disco ball. And they were there to talk about literature.

When Kiara Barrow ’16 and Rebecca Panovka ’16 first launched The Drift literary magazine in June 2020, they didn’t expect hundreds of people would read it, let alone queue around the block to celebrate each new issue’s launch. “It’s exciting that people are interested in reading long-form essays, criticism, short fiction, and poetry, and they want to come to a party and talk about it and meet each other,” Barrow says. “I think that’s a good sign for the literary scene.”

During the past three years, The Drift has become a voice and community for a new generation of writers. The New York Times deemed it “the lit mag of the moment,” the editor-in-chief of Harper’s has praised it, and Drift-branded tote bags have dethroned The New Yorker totes as the fashion staple of the younger literary order. “There’s an audience now for this kind of magazine,” the pair wrote in their first letter-from-the-editors, which went viral: “one in which socialism and feminism don’t entail moralizing; in which political wars are not fought on cultural battlefields; in which an essay isn’t an excuse for self-indulgence; in which there’s more to the media than endless recursive analysis of the media.” The magazine is a response to the old guard, a place for work “by young writers who haven’t yet been absorbed into the media hivemind and don’t feel hemmed in by the boundaries of the existing discourse.”

A few weeks after the party, Panovka and Barrow sat beside each other on a restaurant patio near their apartments in Brooklyn. It’s clear that they’re friends first and co-founders second. “A very common pattern Rebecca pointed out,” Barrow says, laughing, “is whenever we disagree about something, we’ll talk it through, and by the end we’re each convinced that the other was right.” Panovka adds, “We both take each other’s opinions really seriously.”

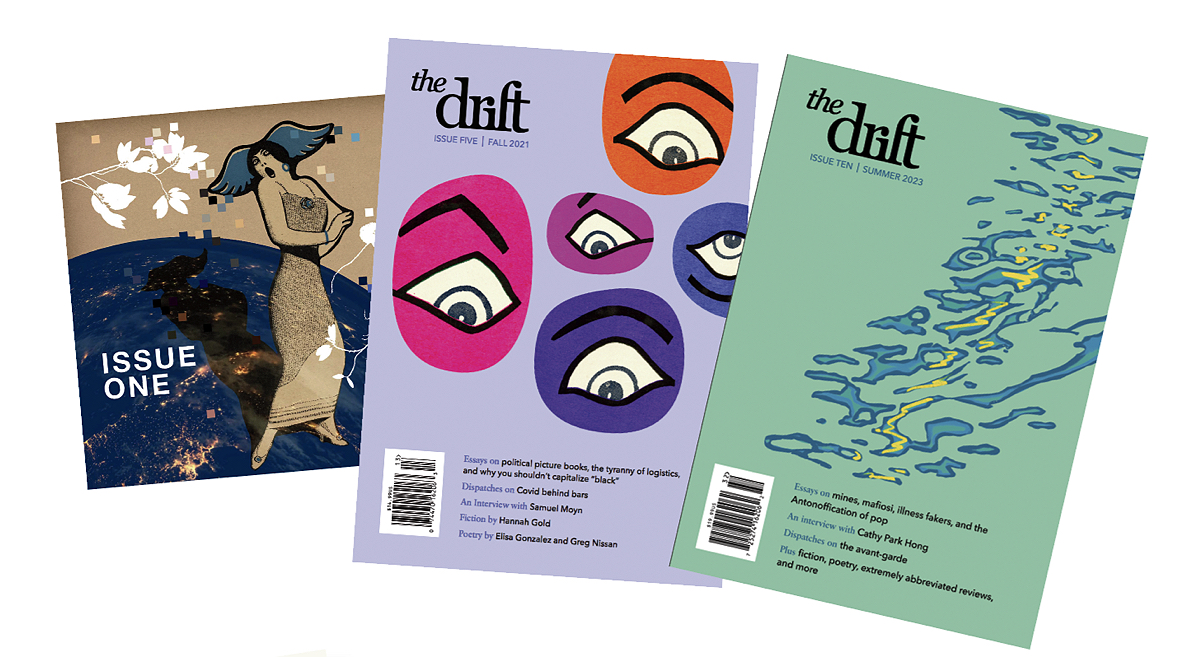

From left: the debut issue (online-only due to the pandemic); the first print edition; the latest issue, published in July

The Drift isn’t their first joint endeavor. They both grew up in New York City, attending private schools on opposite sides of Central Park, and met as undergraduates. They worked together at the Harvard Advocate (Barrow was president) and helped revive the long-dormant Harvard Book Review. After graduation, Barrow headed into book publishing and Panovka to the University of Cambridge to study political thought and intellectual history as a Marshall Scholar. But the pair kept in touch throughout the Trump presidency, trading articles and opinions, both dissatisfied with how superficial and heavy-handed much of mainstream leftist writing seemed.

While conducting research for her master’s thesis, Panovka discovered a socialist magazine called The Masses, which appeared from 1911 to 1917. “These people over a hundred years ago had a striking number of views that we all agree with still,” she says. “Race, imperialism, every kind of hot button issue right now—these are not new hot button issues.” She and Barrow were also struck by the magazine’s tone. “It didn’t take itself too seriously,” Panovka reflects, and had real style, with beautiful illustrations and cartoons.

The pair adopted this lighter tone and fanciful graphics to make a new little magazine for a new era. Since their debut issue, they’ve continued to answer the question: What makes a Drift piece Drift-y? Its emerging writers are not confined by topic: mining, pork farming, and the “inherent racism” of The New Yorker’s Night Life section have all found a place in past issues. Genres span literary criticism, long-form journalism, poetry, fiction, and cheeky 100-word reviews on everything from Thomas Mann short stories to the blooper reel from the film Young Frankenstein. But all Drift pieces aim to add a surprising point of view: for instance, Apple Watches, purported to democratize healthcare, are privatizing it; and streaming platforms are responsible for the rise of the bland maximalism of today’s most influential pop record producer, Jack Antonoff.

The Drift promises young writers three things they can’t often get from larger publications: editors will read their pitch, respond to it, and if they accept it, they’ll spend months carefully editing it together. “We wanted to make a space that would allow writers who hadn’t already made their names to put big ideas on the page,” Panovka says. Its parties aim to be a similarly welcoming gathering spot. “So many [New York literary] parties are invite-only, with a list and a Paperless Post,” she says. “You have to know somebody, or you have to be in the know.” But like its inbox, The Drift’s parties will always be open.

Barrow and Panovka do all this with a small budget and a four-person staff, supported by more than a dozen stipended and freelance team members. While their assistant editor and managing editor are both salaried, Panovka and Barrow pay themselves stipends and have continued book editing (for Barrow) and freelance writing (for Panovka) on the side. The bulk of the magazine’s revenue comes from subscriptions to their triannual print issue and paywalled online articles, but thanks to a multi-year donation from David Zwirner’s contemporary art galleries, they’ve raised their pay rates for writers, held fundraisers in its spaces, and interviewed acclaimed exhibiting artists like Barbara Kruger. A contributor to The Drift’s second issue, Zwirner’s son Lucas said that the galleries—known for provocative works that spark new conversations—see the publication as a likeminded partner: “Magazines like The Drift are essential to a healthy culture of discourse.” The founders’ next big ambition is an office. Barrow says, “We’re starting to outgrow what we can accomplish, meeting in either of our apartments.”

Logistics aside, they find themselves at an inflection point. As The Drift’s influence increases, how will they keep it outside the literary mainstream, to which it was formed as an alternative? The best way, they say, is to stay true to their founding principles: publish new writers and surprising ideas. “When you’re a young emerging writer, you don’t always get the chance to make a really ambitious argument in a 3,000-5,000 word space,” Panovka says. To preserve that space, their magazine must endure. “We’d like to be around in 10 years, in 30 years,” she says. “We’d like to be an institution.”