Late in the second quarter on a sunny, seasonably warm Saturday 110 Novembers ago, the 50,000 spectators crammed into Harvard Stadium trained their gaze on a solidly built, crimson-clad player massaging a football near midfield. In the thirty-fourth playing of The Game, undefeated and defending national champion Harvard was leading archrival Yale 3-2. The cynosure of all eyes was Charlie Brickley—football’s best player, the greatest kicker in the sport’s then 44-year history, and the Crimson’s most potent offensive weapon. From the Elis’ 42, following a Yale punt on which the Crimson had made a fair catch, “Brick” would be attempting a field goal on a free kick (meaning, one Yale could not contest) toward the Stadium’s closed end.

What the onlookers did not know was that, on a play earlier in the game, Brickley had been inadvertently scratched in the eye. His view was so murky that he could barely make out the goalposts. His holder, quarterback Mal Logan, also had to be his guide. “As blinded as [Brickley] was,” wrote Arthur Daley of the New York Times 35 years later, “he still needed only the direction pointed out to him.” Logan placed the ball on the ground. Brickley took two steps forward and swung his right leg. The square toe of his specially designed cleat collided with the football. THUMP! The oval sailed end over end, up and up, then descended, clearing the crossbar with ease and finally landing in the seats of the bowl, perhaps 25 yards in back of the goal line. Harvard 6, Yale 2.

Three more Brickley field goals followed. The final score was Harvard 15, Yale 5—or more properly, Brickley 15, Yale 5. Five field goals in one game was not unprecedented. But Brickley had achieved his feat of foot—four by dropkick and one by placekick—in the most important clash of the season, an early-day Super Bowl. For a second consecutive season, the Crimson finished undefeated and, in an era when Harvard football was big-time, was acclaimed national champion.

Word of Brickley’s performance clattered across telegraph lines. “We today can hardly comprehend the impact of that feat around the nation,” wrote famed football coach Clark Shaughnessy in 1943. “In small Midwestern towns, schoolboys to whom Brickley was a hero gloated over it and practiced dropkicks—pretending they were Brickleys. Garrulous farmers passing on the dirt roads, having heard of it from far away like the presidential election returns, checked their teams to comment on the hardy muscular feat reminiscent of the sporting contests of the old pioneer days. Strangers in city crowds used it as an introduction, and friends employed it in passing the time of day instead of remarking on the weather. Everyone gloried in it; everyone felt vicariously the thrill of it. Everyone had a part in it, shared in it, grew close to Brickley; became a friend of his.”

Fifteen years later, having been found guilty of stock fraud, Charles Edward Brickley stood in Boston’s Suffolk County Courthouse and heard Judge Patrick J. Keating, A.B. 1883, sentence him to 15 months in prison—coincidentally, one for each of the points he had scored on that glorious day against the Elis. This time nobody became a friend of his, particularly at his alma mater.

The 2023 season marks the 150th anniversary of football at Harvard. (Because of the cancellation of the 2020 season due to COVID, this is the 149th season of play.) Ever since May 14, 1873, when Harvard defeated McGill 3-0, the Crimson has boasted hundreds of outstanding performers. To honor the occasion, Harvard Magazine asked a distinguished panel of pigskin philosophers to do the impossible: select an all-time first and second team, along with the Crimson’s top coaches. Our choices appear in “The Sesquicentennial All-Crimson Team,” here.

Among these gridiron stars, the most star-crossed, if arguably the most accomplished, was Charles Edward Brickley, A.B. 1915. In an era when footballers went both ways—playing offense and defense—and substitutions were limited, Brickley was a speedy, powerful, and clutch running back as well as a ball-hawking defensive back; his kicking made him a national celebrity. His career scoring record (291 points) stood for 91 years until it was broken by running back Clifton Dawson ’07—and Brickley would have had more points if almost all of his senior season had not been wiped out by an appendectomy. Moreover, his hard-bitten coach, Percy Haughton, A.B. 1899, in almost all other ways a football genius, allowed him to boot only two extra points, under the theory that conversions would ruin him for field-goal tries. Brickley’s total of 13 field goals in 1912 was not matched at Harvard for 92 years, and it remains tied for second-most in a season, behind the 15 booted by Jonah Lipel ’23 in 2021. His Harvard teams won all 21 games in which he appeared. Had there been a Heisman Trophy in 1913, Brickley would have been the honoree.

Given Brickley’s accomplishments, why are Crimson elevens not playing their home games on the Charles E. Brickley ’15 Field at Harvard Stadium? One reason is that no well-heeled alumnus has suggested it, at least as far as we know. In any case, that would be unlikely: Brickley’s life after Harvard rendered him a pariah in Cambridge and led to an ignominious and early end. He became the veritable forgotten man. There is not even a plaque at the Stadium with his name on it.

The son of a small businessman from nearby Everett, Massachusetts, Brickley first developed his kicking prowess in the town’s playgrounds and sandlots, and on his friends’ lawns. “Many a neighbor’s windowpane suffered as a consequence,” he wrote. He especially mastered the dropkick, which entails the kicker taking the snap from center as if to punt but letting the ball fall to the ground before booting it. It was a favored method of kicking field goals and conversions in football’s early days, when the pigskin was softer and rounder than it is today. “Shorty” Brickley began working out every angle and developing methods that would help him get the kick away before it could be blocked. Eventually, he refined his art form so thoroughly that he became the da Vinci of the dropkick. At Everett High, he set scoring records that would not be broken for 87 years. In 1999, the Boston Globe would name him the state’s greatest schoolboy player of the twentieth century. He was also a standout in baseball and track.

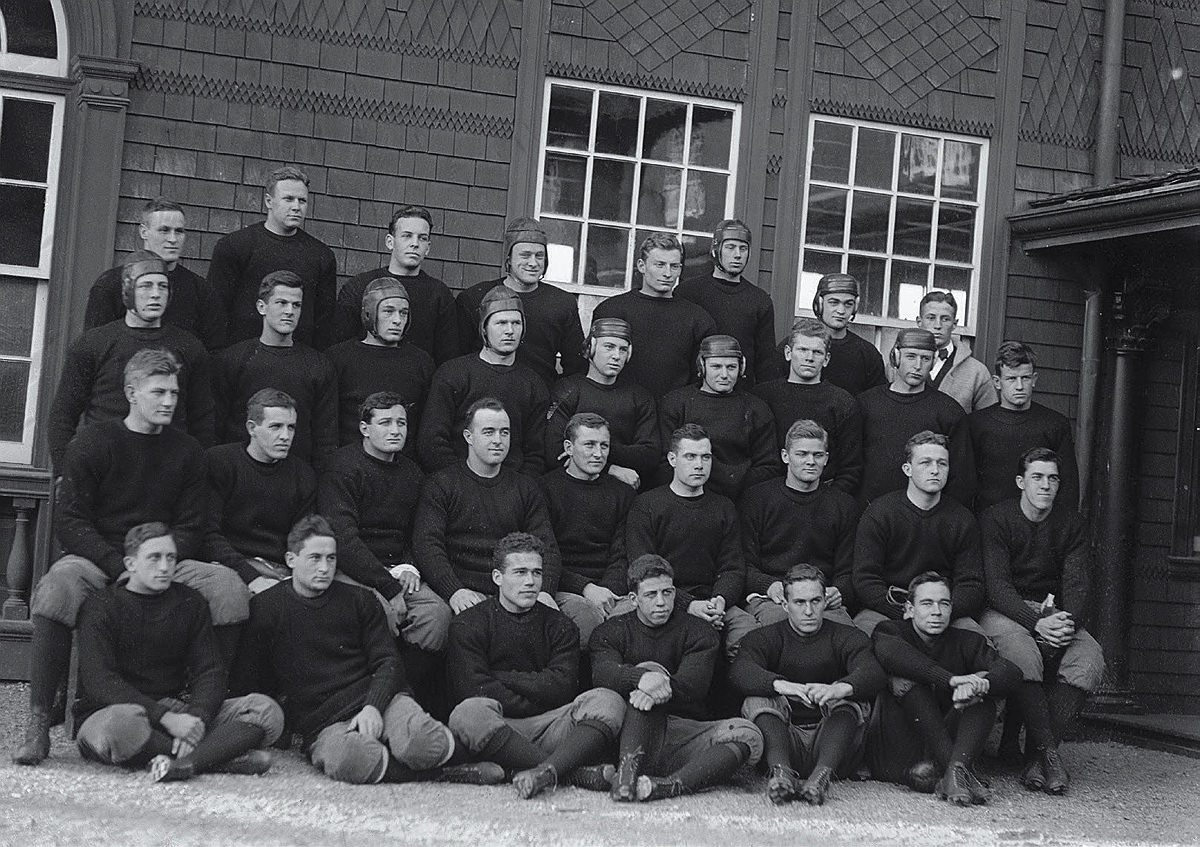

After a postgrad year at Exeter and despite some entreaties from other schools (which apparently offered him “advantages”), Brickley matriculated at Cambridge in 1911. By then he was 5’11” and 190 pounds—large for a running back in those days. The following summer he traveled to Stockholm and competed in the Olympics, finishing a creditable ninth in the hop, step, and jump. Then he was ready for varsity football. As a sophomore, he joined with six other members of the Class of ’15 recruited to form Haughton’s fabled Group of Seven. Their record over their three seasons would be 25-0-2, and five would be named All-America. They would be joined in 1913 by Eddie Mahan, A.B. 1916, who became one of Harvard’s most illustrious running backs.

Brickley was at his icy best in big games. In 1912, at the Stadium against Princeton, with the score 6-6 in the third quarter, he was given a free kick from the Tigers’ 47. As reported in the next day’s New York Tribune, “Carefully he measured the distance. Carefully he directed the placing of the ball. Taking only two short steps, [Brickley] drove it over the goal with the accuracy of a sharpshooter for as pretty a goal as has been seen in many a long day.” Later, he was the primary ballcarrier in the final drive to a clinching touchdown. With the game in hand, he staggered off the field, utterly depleted, “cheered by the 30,000 people today in a way that comes to few athletes. Even the men of Princeton were generous enough to applaud this dashing, brilliant player.”

“Brickley didn’t play for Harvard, he played for himself.”

For two seasons, and despite opponents’ attempts to incapacitate him, Brickley would be similarly unstoppable, culminating in that five-field-goal tour de force against Yale. Earlier in 1913, on a soggy field at Princeton, he had scored the game’s only points, booting a sodden ball for a 20-yard field goal; then, late in the game, he had bailed the Crimson out of a hole with a 61-yard scamper down the right sideline. Along the way, he became Mr. Entertainment: before games he would stand on the sidelines and curve his boots through the uprights, displays that wowed the spectators and stunned foes. As time went on, there was an undercurrent of grumbling among his teammates that he was showboating: that “Brickley didn’t play for Harvard, he played for himself.” Nevertheless, he was popular or at least respected enough to be voted captain for the 1914 season.

In the 1914 season’s second game, a 44-0 thrashing of Springfield, he was in full flower, scoring two touchdowns, dropkicking a field goal, and spearing an interception. The following Friday, an inflamed appendix did what his foes could not. Brickley’s career was done, save for one forlorn extra point during Harvard’s 36-0 blowout in The Game. As the wobbly kick barely cleared the crossbar, referee Nate Tufts signaled it was good. It was almost an afterthought.

In the 1920s, Charles E. Brickley completed a journey from acclaim to disgrace.

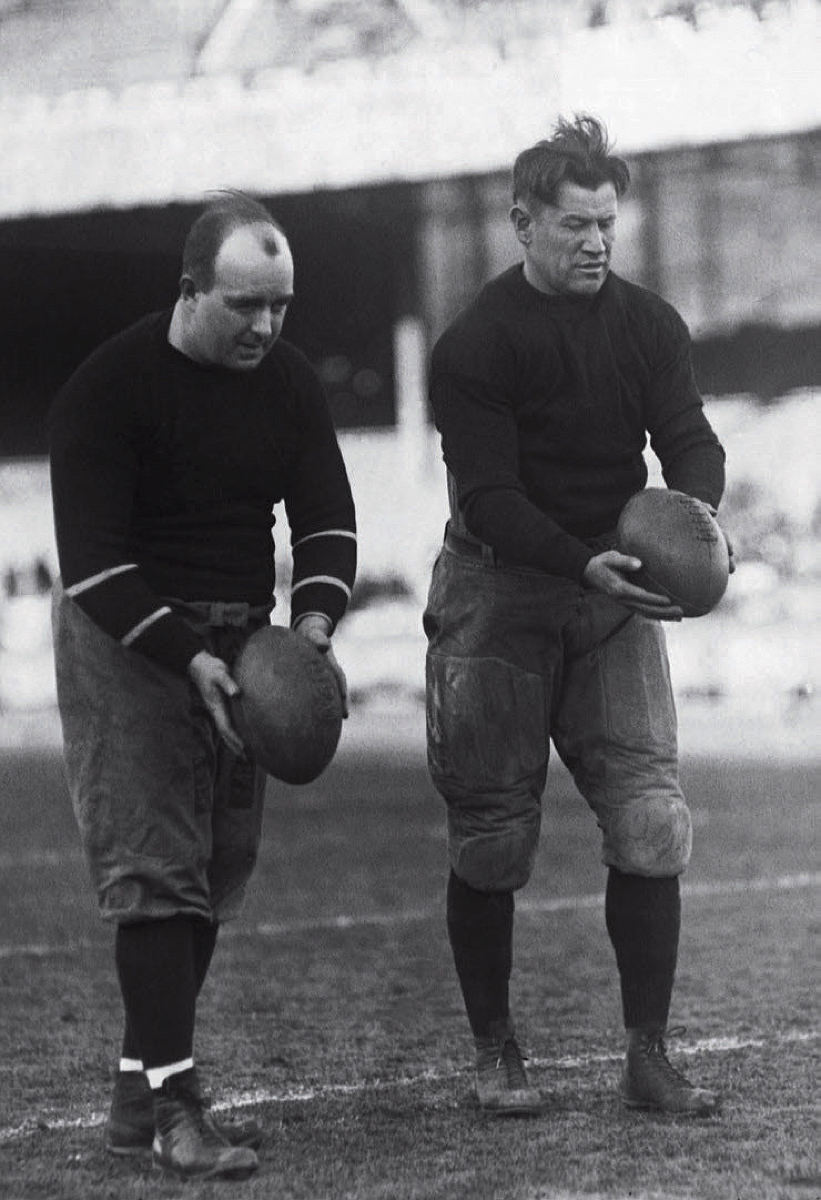

It’s possible that Charlie Brickley’s greatest crime was being born 10 years too early, before newsreels and the newly minted National Football League (NFL) made college football stars instantly marketable. His post-Harvard life had started promisingly enough. After graduation, Brickley kept his hand (and foot) in the sport, bylining a syndicated newspaper column and coaching at Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Boston College, and Fordham. Upon America’s entry into World War I, he served in the Naval Reserve. In 1921 he put together a team in the nascent NFL, the New York Brickley Giants. One Sunday, hoping to goose the gate at the Polo Grounds, he competed in a kicking exhibition against Jim Thorpe, whom he had met when both competed in Stockholm.

Married to New York society girl Kathryn E. Taylor and with two young sons, Brickley entered the arena of Wall Street. He soon was making $500 a week, but in 1920 chose to begin his own firm, Charles E. Brickley & Co. Brickley found the going much tougher than he had against Princeton or Yale. He bought a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, but in 1921 his firm was dissolved. He and other brokers were defendants in a suit brought by the Back Bay National Bank. They were accused of not repaying a $15,000 loan. Two months after the firm’s dissolution, he was sued for not repaying a $10,000 loan given him by one Joseph Jackson. As the New York Times put it in a front-page story, “the action revealed that [Brickley] had been threatened with a horsewhipping in the Harvard Club by Mrs. Miriam Reinhardt,” Jackson’s sister.

Brickley then went to work for the Bigelow Hartford Carpet Company. In 1923, he was among those indicted in a swindling case involving the company’s stock. It would be two years before the case would come to trial. After five hours of deliberations, the 10-man jury declared Brickley not guilty.

Would exoneration keep—or, depending on how you look at it, put—Brickley on the straight and narrow? Not according to four indictments (totaling 17 counts) handed down by a Suffolk County grand jury on August 5, 1927, charging him with forgery, larceny of stocks and bonds worth $35,588, and, since December 1, 1925, operating a bucket shop (in which stocks were illegally speculated upon but not actually traded).

The case came to trial the following February. Brickley spent two-and-a-half days on the witness stand. He could not wriggle out of this one as if it were an opposing tackler. On March 1, a jury found him guilty of four counts of the indictment, Keating having thrown out many of the others. Remanded on $12,000 bail, he was facing hard time.

On March 22, the day of sentencing, presenting the closing arguments for Brickley was William H. Lewis, L.L.B. 1895. As Crimson center “Bill” Lewis (playing while attending law school, when graduate students were permitted to compete), he had been the first African American All-American. Lewis, known as a spellbinder, came in with the heavy oratorical artillery. His voice breaking, he declared, “I stand here more as friend of Charlie Brickley than as his counsel.…I have seen him borne from the field on the shoulders of those who idolized him. He has not played the game of life quite so successfully. I have told him that the stock market game was not his game….Give him a chance, give him a chance to go out and play a game that he can play.”

Keating was unmoved. He sentenced Brickley to 15 months in the Charles Street jail, later shortened to a year. Brickley began his sentence on May 17 and spent the next seven months variously at Charles Street, the Deer Island House of Correction (where he managed the baseball team), and the State Prison Camp at Tewksbury. After an illness, he was paroled just before Christmas.

On December 14, 1949, Charlie Brickley and his older son, 30-year-old Charlie Jr. (Chick), were at Reuben’s Restaurant at 6 E. 48th St. in Manhattan. Brickley’s stock-swindling conviction in the ’20s had left him, in the words of Boston Herald columnist Bill Cunningham, “broke, convicted and shunned by his classmates and his college who felt he’d rubbed much lustre from his shining shield. And, undoubtedly, he had.” When in financial straits, Brickley would put the arm on some of his teammates for funds.

He had led an itinerant existence. For a time, he managed the health club at the Roosevelt Hotel. (Imagine Joe Namath handing out towels at your local gym and you have a notion of how far Brickley had fallen.) He always was willing to provide informal kicking exhibitions and to coach kickers; Chick, in fact, had inherited the old man’s knack and played for, of all schools, Yale.

After Pearl Harbor, in his early 50s, Brickley had tried to re-enlist in the Navy. Not surprisingly, he was turned down because of his age. So he traveled to Wilmington, Delaware, where he became a pipefitter’s helper at the shipyard there, earning $48 a week on the 4 p.m.-to-midnight shift. After the war, he returned to New York City, where he lived at the unfashionable George Washington Hotel on West 23rd St. and landed a position as an advertising salesman. He also checked into Roosevelt Hospital twice with heart complaints.

Now, on this night at Reuben’s, another patron recognized Brickley and began to disparage him. An uncharacteristically puckish account the next day in the New York Times reported that “Words were exchanged, blows aimed, glass and crockery tinkled, whistles blew, a blue flying wedge converged on Brickley senior and junior and [threaded] its unwanted way through the melee, so the preliminary testimony went.” One of the policemen, who clearly could compare notes with blue-clad Yale tacklers from four decades earlier, said “it took about ten of us” to get the two Brickleys into a prowl car for their trip to the West 51st St. station. At the hearing on December 28, cooler heads and better feelings prevailed. Amid handshakes, Judge Charles F. Murphy dismissed the case.

That night, at the George Washington Hotel, Brickley’s friend Henry Garrity, a former Princeton football player in 1920 who lived in the next room, heard groans from Brickley’s room. When he investigated and saw Brickley’s condition, he summoned Nate Tufts, the hotel manager. This was the same Nate Tufts who had refereed the 1914 Yale game and signaled that Brickley’s wobbly final kick was good. Soon, a physician from nearby Bellevue Hospital, Alan Moody, arrived. At 11:15, he pronounced Brickley dead of a heart attack at age 58.

On January 2, 1950, Charlie Brickley’s life was celebrated in a solemn high requiem Mass at the Immaculate Conception Church in Everett. One thousand mourners were in attendance. Among them were four of Brickley’s teammates: Mal Logan, Eddie Mahan, Bob Storer, and Wally Trumbull. Quality, perhaps, if not quantity. The Harvard Crimson gave his passing but perfunctory notice.

The College Football Hall of Fame opened its doors in 1951. Percy Haughton and Eddie Mahan were in the charter class. During the next two decades, several other Crimson immortals were enshrined. Conspicuously omitted was Charlie Brickley. Despite his worthy record on the field, he fell afoul of one of the major criteria for admission: While each nominee’s football achievements are of prime consideration, his post-football record as a citizen is also weighed. Nor was Harvard eager to press his cause. In recent years, efforts to resurrect Brickley’s candidacy have been unavailing.

On October 27, 1967, the Harvard Varsity Club inaugurated its own Hall of Fame—without Brickley. (“Guess whose name was missing?” commented the Globe.) In 1970, after a de facto probation period, he was inducted.

Reportedly Brickley took his humiliation in stride. “I have never known a man who shouldered his cross with greater acceptance, or with less complaint,” wrote the Herald’s Bill Cunningham. And so we are left with this counterfactual: If Brickley’s life had been as straight as his field-goal aim, would the award that annually is handed out to the best college kicker be named not the Lou Groza Award but the Charlie Brickley Award?