On the eve of her installation as the thirtieth president, the Harvard Gazette asked Claudine Gay about the most significant possibilities she saw before the University she now leads. Alluding to her remarks last December 15, when her election was announced, she said, “I talked about the opportunity for Harvard to be more connected to the world by centering the most pressing challenges that the world faces as University priorities. For me, those include…all the ways in which democracy is faltering around the globe, the climate crisis, and inequality, to name a few”—plus the realm of discoveries in the life sciences (with their potential to address global needs, too).

That is one through line Gay has established to date for her presidency, from her election through the choice of topics for the academic symposiums on the morning of September 29 (read a report here), and then in her afternoon installation address. The other theme—reflecting her status as Harvard’s first black president, and in the wake of the Supreme Court’s June 29 ruling against affirmative action (just 36 hours before she took office)—concerns the diverse people the Crimson community embraces. Now, she has drawn on her life story to embed those ideas in a vision of Harvard, inviting faculty, students, staff, and alumni to take up that narrative at a time when much of the public has soured on higher education (and many other bedrock institutions).

Opening the term at Morning Prayers on September 5, Gay riffed on her “reality television” career, as a five-year-old participant on Romper Room (she got kicked off for excessive, spontaneous curiosity). That was an early step leading to her present, “[p]ropelled by belief in the power of education, the power of curiosity and ideas, the power of attentive and industrious work—instilled in me by my mother and father, nurtured in me by my teachers and my mentors.” Less than a decade away from Port-au-Prince, her parents were finding a place in a new country for themselves and their children. Addressing those attending, who knew some things about curiosity and education, Gay hoped that students’ and professors’ Harvard lives would be shaped by the recognition that the University is “not just for the people who are fortunate enough to be considered members of our community. Our reach, our embrace, our obligation is wider than that—and can and should be wider still.” She concluded with a charge for their work here: “Each of us has a hand in deepening the connection between our mission and our society. That connection is what matters to me.” In sum, a dual call to welcome to learning and discovery all who might benefit; and to focus those core institutional purposes on society’s urgent needs. (Read more at harvardmag.com/morning-gay-23.)

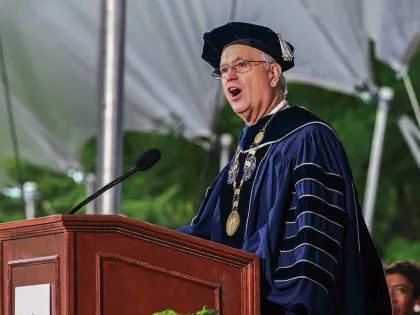

The question of who belongs at Harvard was addressed throughout the installation, directly and by example. In his faculty welcome to Gay during the ceremonies Friday afternoon, Tommie Shelby, Titcomb professor of African and African American studies and of philosophy said, forthrightly, “Claudine…is Harvard’s first black president.…I celebrate this precedent…because of what it says about Harvard and our place—the place of all who ever wondered if they belong—within it.” Gay’s background, experience, and scholarship, he continued, “will be enormous assets as we maintain and deepen Harvard’s commitment to diversity and inclusion,” and then explained how W.E.B. DuBois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. 1895, lamented that as a student he “was in Harvard, but not of it”—a separation now perhaps erased.

In her address, Gay went even deeper into Harvard’s history, recalling that “Not four hundred yards from where I stand, some four centuries ago, four enslaved people—Titus, Venus, Bilhah, and Juba—lived and worked in Wadsworth House as the personal property of the president of Harvard University.” Her immigrant story, she noted, is not their narrative, “But our stories—and the stories of the many trailblazers between us—are linked by this institution’s long history of exclusion and the long journey of resistance and resilience to overcome it.”

Because of the personal courage of “all those who walked that impossible distance, across centuries, and dared to create a different future,” she continued, “I stand before you on this stage…with the weight and honor of being a ‘first’—able to say, ‘I am Claudine Gay, the president of Harvard University.’”

The demonstration effect was equally vivid. At the student-dominated “Arts Prelude” in Sanders Theatre honoring Gay the night before, singer-songwriter LyLena Estabine ’24 introduced a performance of her “Ayiti Cheri” (Dear Haiti). The song draws on her heritage, and Gay’s, and was arranged by Yosvany Terry, senior lecturer in music and director of jazz ensembles, who accompanied on saxophone. (Terry’s family shares Haitian roots, too.) Diverse other participants included Branden Hart, A.L.M. ’24, of Chickasaw and Cherokee descent, and deaf student Shelia Xu, M.P.P. ’26, who signed to an interpreter—and taught Gay, in the audience, to sign, “Welcome to Harvard.” David Johnson Aboge ’25 offered his greeting in Swahili, his first language; he described his journey from Kenya to a new community at Harvard. Among many talented ensembles, the Asian American Dance Troupe performed, and the incandescent bass-baritone Davone Tines ’09 silenced the auditorium with his rendition of “Lift Ev’ry Voice,” often called the black national anthem. (Read a full report at harvardmag.com/perform-prez-23).

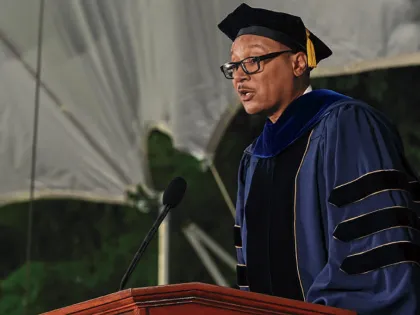

In the September 29 exercises, Elizabeth Solomon ’79, A.L.M. 20, a member of the Massachusett-Ponkapoag Tribal Council, gave the land acknowledgment; Terry did a haunting sax solo of “America the Beautiful”; and Félix V. Matos Rodríguez, the first Latino leader of the City University of New York system—the very model of higher education on a vast scale—presented the welcome from that sector. (Gay’s parents were students at City College, part of CUNY.) The student speaker was Natale Sadlak, M.D. ’24—the daughter of immigrants from Poland and Malaysia, and herself a gay doctor-in-training whose research focuses on care for marginalized communities.

Whatever remains to be done to extend Harvard’s welcome, it bears remembering how far the place has come. At the May 31 memorial service for Henry Rosovsky, president emeritus Derek Bok recalled offering Rosovsky the Faculty of Arts and Sciences deanship in the fall of 1973—a half-century ago. The latter, a Jewish refugee from Nazism, hesitated, Bok remembered, saying, “I am a very ‘ethnic’ person” and “I’m not sure Harvard is ready for a very ethnic dean.” Bok observed that Rosovsky was the best person for the job, and the appointment—brilliantly successful—was made. Gay ascended to the same deanship in 2018, and has now, as president, indeed become a “first.” It is a different, better Harvard from 50 years ago.

Amplifying her message about courage, Gay summoned the University to be institutionally courageous, probing the boundaries of “Why?” and “Why not?”—the intellectual spurs “to question the world as it is and imagine and make a better one. It is what Harvard was made to do.” (Her full text appears here.)

Her answers to those questions led, first, to the commitment to “open inquiry and freedom of expression”—and to “diversity—of backgrounds, lived experiences, and perspectives—as an institutional imperative,” given “the learning that happens when ideas and opinions collide.” The specific prompts to such inquiry and academic action (the why not?) included such examples as “Why not improve health care in Haiti and Rwanda?” (as the late Kolokotrones University Professor Paul Farmer sought to do) and “Why not get the innocent off death row?” More broadly, Gay asked why not extend Harvard’s education and collections to as much of the world as possible, directly and through partnerships with other institutions.

“Why here?” she asked. Because, Gay said, “Harvard is blessed with outsized capacity to seek truth and to do good, imbued with awesome potential to change the lives of individuals and the prospects of communities” by helping to “anchor our democracy,” engage in “the struggle against tyranny, poverty, disease, and war,” and address climate change. All the more so today, when a substantial majority of Americans believe higher education has a baleful effect on the country. Her stark answer to the question “Why now?”: “Because ‘now’ needs us so that ‘later’ has a fighting chance.”

In her peroration, Gay charged the sodden throng to “summon the courage to be the Harvard that the world needs now,” and urged, “Let us be courageous together.”

Gay’s life experience embodies her parents’ courage: traveling to a new country to pursue a better life and seeking the growth that only education can provide. Less known are the fateful choices Gay herself made with that endowment from her parents and professors. One was to pursue the liberal arts, rather than preprofessional studies. Another came after her doctoral work, when she spurned offers for academic positions, instead venturing into consulting. Within months, she recognized that only within the academy could she pursue questions of fundamental import, with the freedom to go where intellectual inquiry would lead her. Those choices took courage, too.

Opting for a life in higher education has brought her a stellar career, now at Harvard’s helm. Drawing on those life lessons, Gay hopes to inspire today’s students and scholars to a high calling: applying the privileges and intellectual prowess of this community to address society’s greatest needs. Doing so, she clearly believes, offers the surest path both to personal fulfillment and to closing the gap between institutions like this one and the impatient, fractured society beyond—in which higher education is inextricably embedded. A worthy summons to Crimson courage indeed.

Read a complete account of the installation ceremony and speakers at harvardmag.com/gay-install-23.