Claudine Gay arrived in Cambridge in the fall of 1992 as a first-year graduate student, lugging the things that seemed most essential to her success: a futon, a Mac Classic II, and a cast iron skillet for frying plantains. The futon, no doubt, was standard grad-student gear. The computer pertained to her status as a nascent social scientist in an era of increasingly quantitative scholarship. And the plantains traced back to her roots, as the daughter of immigrants from Haiti.

Accompanying those things were mental constructs that would really be essential to her success. Higher education figured strongly in her parents’ narrative. They came to the United States with little but managed to put themselves through college while raising their son and daughter. Gay’s mother became a registered nurse, and her father, a civil engineer, “and it was the City College of New York that made those careers possible,” she said when her election as the University’s thirtieth president was announced last December 15. That step up the ladder was accompanied by strong views about the ensuing rungs: “College was always the expectation for me,” she continued. “My parents believed that education opens every door. But of course they gave me three options—I could be an engineer, a doctor, or a lawyer—which I’m sure other kids of immigrant parents can relate to!”

Then, as so often happens, a student given access to outstanding education found her trajectory rerouted. After Phillips Exeter Academy and a year at Princeton, Gay transferred to Stanford (B.A. ’92) and then came back east for her Ph.D. in government, conferred in 1998.

Her undergraduate studies “ignited everything for me,” she said in December. “That’s where I discovered the reach of my own curiosity, where I experienced firsthand the detective work that is research and learned for the first time that knowledge is created and not just passed on. And it’s where I found what I wanted to do, what I felt born to do with my life.” As also so often happens, that discovery prompted some conversations, which she characterized diplomatically: “[L]et’s just say that my becoming an academic was not what my parents had in mind. So, my decision to pursue a liberal arts and sciences education was a leap of faith—really, for all of us. But thankfully, my parents supported my choice. And by virtue of that fact, my life’s path took shape”—mostly.

Gay was just shy of 53 years when she took office on July 1, an age in the middle of recent presidents at the start of their administrations, but her years seem less telling than the era in which she grew up. Her arrival represents a generational change in Harvard’s leadership, the first move beyond the cohort who attended college in the 1960s and early ’70s. Drew Gilpin Faust, a student at Bryn Mawr, marched in Selma in early 1965 (see book excerpt here), helping to spur passage of the Voting Rights Act—the precursor to Gay’s doctoral research three decades later. Among other disruptions, the April 1969 Harvard strike and state police bust at University Hall (the beginning of the end of Nathan M. Pusey’s presidency) formed the background to Lawrence S. Bacow’s arrival at MIT that fall: as he related in an MIT oral-history interview, when he got to campus amid a protest, his father said, “If you get arrested, don’t call home.” Antiwar demonstrations were far from over the next year, when Gay was born (the Kent State shootings took place in May), but a transition from street protest to participation in politics was underway. The tumults and tragedies of the 1960s began to abate.

Her election attracted less external attention for its generational meaning than for the fact that Gay is Harvard’s first black president. Barely noticed, but consequential in thinking about what she brings to the office, is another precedent: Gay is the first Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) dean to move across the Old Yard to the president’s office in Massachusetts Hall. As support for the liberal arts ebbs, her background in curiosity-driven scholarship and teaching is notable. And because the autonomy of the University’s myriad schools and programs can often impede important interdisciplinary research (rather than enable it), putting at the helm the person who just led the institution’s most multidisciplinary, heterogeneous faculty appears useful training for academic battles—and progress—to come.

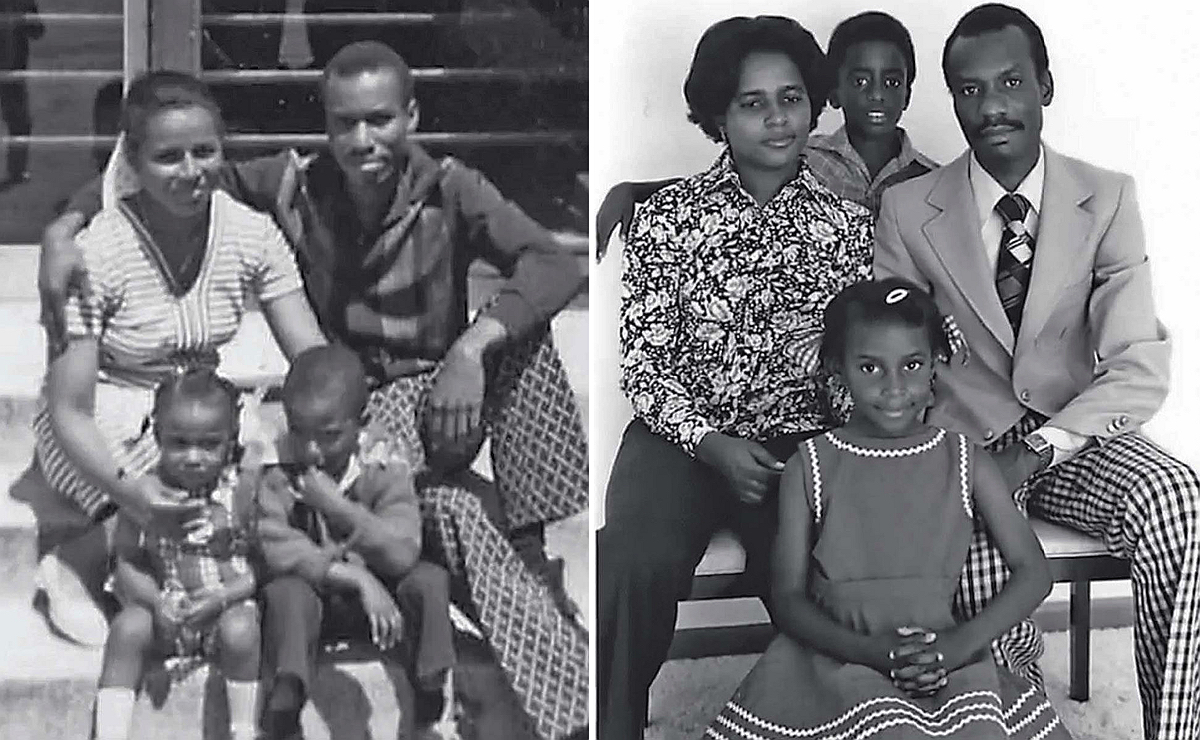

Portrait of the young scholar: two Gay family photos of Claudine, older brother Sony Jr., and parents Claudette and Sony

Photographs courtesy of Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

A Haitian immigrant family ascending—a made-in-America success story. A country some decades beyond its worst moments—having finally acted to enfranchise the descendants of slaves—now moving in fits and starts to incorporate fully people who have been outsiders. A young, intense student interested in race in American politics—embarking on the work that precedes a life in scholarship. Those were among the threads being woven together in 1992 when Gay, then 22, moved her stuff into Haskins Hall.

Her path there was not quite direct. Gay has spent most of her life within elite, private educational institutions, but she entered that realm with a worldly background. Her father’s U.S. Army Corps of Engineers assignments took the family from New York to Georgia and Saudi Arabia (where she was in school for second through ninth grade, the last year offered). Although within weeks she found the culture of Princeton too familiar and comfortable after prep school (hence the move west), campus life proved congenial. She thrived, all the while training her scholarly eye on important subjects outside the academy. Those commitments—to the work of the university, and its impact on the wider world—helped make her the leader she is today.

In college, Gay recounted during an early-July conversation in her new office (outfitted with the furniture she had as FAS dean), she wanted to understand Haiti. She knew the culture, from her very Haitian household, and some history, but “couldn’t make sense of the politics, the economy, the social organization.” That led to work in the social sciences at Stanford, with an emphasis on economics “as a concession to my parents.” She studied development economics and public economics, seasoned with history and political science courses on the side. As she considered graduate school, a teaching fellow wisely counseled Gay that her interests wouldn’t be taken seriously within an economics program. By then feeling less pressure to satisfy her parents, Gay pointed herself toward government.

“We were glad to admit her,” recalled Katherine Tate, assistant and then associate professor of government at Harvard from 1989 to 1993, a member of the department’s admissions committee. Among many talented applicants, “She soared,” Tate said recently, and “turned out to be a very talented student.”

It was a challenging time to be a student like Gay. The government department little resembled the faculty today: among 57 faculty members listed in the 1992-93 Courses of Instruction, there were two women full professors (one of whom died that September); and six women associate and assistant professors, none of whom remain at Harvard, and one woman instructor (and three of those seven were on leave that fall). Antiwar activism had long since ceased to be a feature of college life, but the Crimson reported on early 1990s Harvard protests demanding more diverse faculties.

“It was a different place then,” Gay recalled. “It’s still a journey,” she said, but the department is “much more diverse” in many dimensions, including gender and race. What made all the difference in her experience, she continued, were strong mentor-advisers “who from the moment I stepped on campus took me seriously as a scholar” and challenged the new student “so my ambitions matched the talent they saw in me.” She credits those connections for enabling her to succeed and “at the end of the day, have a positive experience,” despite coming from a background so obviously different from those of most faculty members.

With that support, Gay’s intellectual focus evolved. Pforzheimer University Professor Sidney Verba (now deceased), an especially influential mentor, was a preeminent scholar of political participation—work complementing Gay’s “core interests in democratic citizenship.” That drew her to American politics. Although Tate departed early in Gay’s graduate studies (she is now professor of political science at Brown), she was influential, too. A scholar of race, gender, ethnicity, and politics, she noted that the film of Rodney King being beaten by Los Angeles police officers had horrified Americans in early 1991, and Anita Hill confronted Clarence Thomas with claims of sexual harassment during his Supreme Court confirmation hearings that October: headline reminders of festering racial and gender inequities that coincided with Gay’s college years. The title of Tate’s 1993 book, From Protest to Politics: The New Black Voters in United States Elections (Harvard University Press), recurs as a thematic phrase in Gay’s dissertation. Joining Verba and Tate as dissertation advisers was Gary King, then professor of government and now a University Professor himself—perhaps the leading developer of quantitative research methods for social science. That proved a perfect fit for Gay’s comfort with quantitative analysis, “a way of thinking and understanding the world that’s always appealed to me.”

Thus equipped, Gay set out to explore how citizens perceive and interact with the political system. Under the Voting Rights Act, the number of black officeholders had risen dramatically, giving political scientists plenty of data to study those officials’ roles and resulting changes in policy. But Gay turned the telescope around, redirecting attention to the governed, focusing on “the impact of black congressional representation on the political behavior and political attitudes of constituents.” It was a testable effect within the larger topic of descriptive representation: what happens when groups are represented by individuals whose characteristics and experiences resemble their own.

Determining how constituents act and what they believe turned out to be a formidable task. As King noted recently, precinct voting records were “stuffed under desks, deleted, or neglected,” so he and Gay collaborated on a systematic effort to gather accurate results for the elections she needed to evaluate. They then had to be reconciled with U.S. census records, the source of information on local populations’ characteristics. After an “enormous, painstaking effort,” King said, Gay had usable data.

And then what? For each election, census data could be used to specify the racial composition of the electorate, and the precinct results to calculate the percentage of people who went to the polls. But those separate data sets did not reveal the percentage of potential black and white voters who actually cast ballots. Gay determined that crucial metric by ecological inference, a statistical technique importantly improved by King during the 1990s—now the standard method for gaining clues to individual behavior from aggregate data.

What emerged from all that work? In her dissertation, “Taking Charge: Black Electoral Success and the Redefinition of American Politics,” Gay reported, in the restrained language of social science, that “the presence of black congressional representatives has reshaped the contours of mass politics…by changing the face of the participant community.” Overall, the advent of black representation “has precipitated a decline in white political engagement” and a sharp realignment in the remaining white voters’ partisan preferences. In contrast, black Americans’ party preference was reinforced and their voting turnout was not “decisively” altered.

These were significant findings. Although the transition to elected black leadership (descriptive representation) had only a modest effect on black voters’ turnout, they did feel more likely to be heard and sought out: a sign of incorporation and their investment in the system. But among white voters, turnout declined, often dramatically, and “defection from Democratic politics is clearly the rule.” Passively or actively, white Democrats acted to “reject black representation.” Compared to white counterparts, black congressmen “can lose nearly 40 percent of the white vote due to their race alone.” Thus, whatever benefits previously underrepresented voters perceived with the advent of descriptive representation, the salience of race to white voters prompted a forceful counterreaction.

Gay’s research yielded credible, valid findings. “That’s what you want in a scholar. She answered the question in the best way.”

In King’s assessment, it was possible to conduct this kind of research “in a half-baked way, in a politically charged way, in a superficial way—but you wouldn’t know if it was true.” Gay, he said, did the work to produce credible, scientifically valid findings. “That’s what you want in a scholar,” he continued. “She answered the question in the best way possible.”

Accordingly, the dissertation can be read today for meanings beyond its carefully constrained social science. Her work on the effects of incorporating a more diverse population helps explain how the political Earth has moved. Given that congressional districts are regularly redrawn, the differential effects in turnout and party affiliation she found would create strong partisan incentives to rejigger district lines and alter the rules governing elections: American politics circa 2023.

Within a few years, Gay would draw such conclusions more directly. In a 2001 American Political Science Review article drawn from her graduate work, the then-Stanford assistant professor summarized the separate voter responses to minority representation she had found, and then observed, “(This dichotomy puts into doubt any hope that black electoral success might lead to an attenuation in racial conflict.)” That combination of meticulous research, often challenging social-science assumptions, with awareness of its role in shedding light on the world at large, would be the hallmark of her scholarship to come.

For all the cerebral discipline doctoral research entails, it is not entirely a lonely pursuit. Acknowledging her sources of inspiration, Gay noted her gratitude to Chris Afendulis, whom she met as they both began graduate study in the government department: “an essential colleague and dear friend” without whose “intellectual energy, love, sanity, and humor” her dissertation would never have been finished. Another quantitative social scientist, he received his doctorate at the 1998 Commencement, alongside Gay—in turn expressing gratitude for her “comments, cheerleading, emotional guidance, and love” as he wrote his thesis.

Gay also cited her “wonderful parents” and older brother and observed, “My mother returned to school just as I was preparing to enter the real world. I only hope that I can take some of her courage with me.”

As Gay set about entering that real world, she was in strong demand on the academic job market, garnering several invitations for interviews. During one, Gary King recalled, a department chair phoned to say, “The department has broken out in spontaneous unanimity” in favor of hiring the young scholar, even before formal deliberations. Given the caliber of her work, King wasn’t surprised—until Gay called a few hours after the interview to say she didn’t want to pursue the position, nor to go into teaching or academic research.

That was then: a 1998 Harvard Magazine Commencement photograph captured, but did not identify, newly minted Ph.D.s Chris Afendulis (facing camera) and Claudine Gay (face turned), who were then working as consultants. A quarter-century later, firmly embedded in academia, the couple could no longer maintain their anonymity on campus.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

“I was 26, I was finishing my Ph.D.,” Gay recalled, “and I realized that from Head Start to Ph.D. I had literally never not been in school.” Again, as in the transition from Exeter to Princeton, “Everything felt very familiar,” and once again she “needed to shake things up.” Somewhat anxiously, she called Verba and King to discuss her doubts, only to find them “totally supportive, as great mentors are. They said they’d keep the porch lights on.”

Dissertation complete, in the summer of 1997, Gay joined Strategic Decisions Group (as did Afendulis). In the firm’s Boston consulting office, she applied her analytical skills to clients’ assignments. “I liked the teamwork aspect of it,” she said, after her solitary scholarship. But being on assignment differed from having a “mind of my own,” and the life cycle of commercial projects necessarily precluded digging as deeply into subjects as she preferred. She realized “this is not me—and what is me is the academy.”

Gay called her mentors again, and “They were great”—again. She found herself “stepping right back on the treadmill, but this time feeling that I was actually making a choice—it wasn’t just the 23 years of hydraulic pressure of being in school.”

From her 2000 return to Stanford, Gay began a decade and a half as a faculty member. Among multiple options, she chose the Cardinal’s offer of a political science assistant professorship because it fit professionally and personally: she had enjoyed her undergraduate experience, and her parents had moved to California. Since that recommitment to academia, Gay said, she has felt “very at home on the college campus”—and the feeling has obviously been reciprocated. She was promoted to associate professor, with tenure, in 2005. Life progressed happily in other ways, too: she and Afendulis married in 2003.

But there was still more shaking up to do. As she focused on political inequality, Gay said, she increasingly felt that the field’s most exciting scholars were at Harvard; when the opportunity arose to relocate, it was an “easy decision to make.” (It wasn’t quite so easy to effect; as the couple moved to Cambridge, in 2006, they were expecting a child; son Costa was born in November, so Gay took the fall semester off, but resumed teaching in the spring.)

To her responsibilities as professor of government, Gay added a joint professorship of African and African American studies in 2008 and became Cowett professor of government in 2015 (the year she began her transition to administration, as FAS’s dean of social science). During that period of teaching and research—paced by the usual research leave and a 2013-2014 Radcliffe Institute fellowship—she said, “My life felt professionally very full.”

As a mentor, she emulated the professors who had enabled and enriched her own graduate study. Porsha Cropper, Ph.D. ’12, recently remembered her sophomore year at Stanford, when she talked her way into Gay’s graduate course on race and place in American politics. It was a revelation, Cropper said; pivoting from human biology, she began pursuing politics, sociology, and comparative studies of race. Echoing Gay’s own undergraduate experience, “She was among the first to spark my interest in scholarship and learning,” said Cropper, who is now senior program officer at the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, in Los Angeles. That spurred an interest in graduate study—introducing her family to the other meaning of “doctor,” she said.

Gay’s questions led to “the most comforting, supportive conversation I’ve ever had. She’s one of the most effective listeners…in my life.”

After earning her B.A. in 2005 and working for a year, Cropper by chance enrolled in the Harvard Kennedy School’s social policy doctoral program just as Gay joined the FAS. Among her dissertation advisers, Cropper said, Gay became “so central—that one person who was going through all of your chapters, pushing you, challenging you on your methods.” She recalled Gay always asking, “Why is this question interesting and why do we care?” Their interactions prompted her to say of her research, “‘Oh, I never thought of that before.’ Claudine is really great at helping you move beyond [a rote] ‘This is my topic, this is my research, I’m done.’” And like her own mentors, Gay remained present when Cropper decided not to pursue an academic career, reaching out to ask, “What’s going on? What are you thinking of doing?” That led to “the most comforting, supportive conversation I’ve ever had,” Cropper said. “She’s one of the most effective listeners I’ve ever had in my life.”

Ariel White, Ph.D. ’16, who did go on in academia (she’s now Silverman Family Career Development associate professor of political science at MIT), also recalled Gay’s unstinting attention as an adviser. “The one thing I remember most…and that I try most to emulate in working with my own students,” she said, is that if they had scheduled a meeting, “She would be ready to talk to me, would have read anything I sent over,” and would be prepared with penetrating questions. Gay was “fully, 100 percent focused,” White said: no phone calls, no interruptions. “We’d just close the laptop and focus on one thing.”

A similar narrative of academic drive emerges from Gay’s work in the classroom. Jennifer L. Hochschild, Jayne professor of government and professor of African and African American studies, who taught a graduate course, “Racial and Ethnic Politics in the United States,” with Gay several times, said her colleague provided a quantitative perspective while Hochschild focused on political history and philosophy, comparative politics, and exploring categories of race and ethnicity. But they were careful not to silo their material and methods, Hochschild continued, giving the course breadth “substantively and temperamentally.” As Gay presented data arrayed along X and Y axes, Hochschild would ask, “Why those data?” And when Hochschild led, Gay would ask the students, “Can we actually believe the data and analyses here?” It was “great fun to teach with her,” Hochschild said, “in part because she’s very smart and analytic.”

The intensity and focus are apparent in Gay’s research, too. Her scholarship—from a paper on black women’s perspectives on race and gender (with Tate) to analyses of Latino and African American voting in majority-minority districts in California and of the effects of economic disparity on blacks’ attitudes toward Latinos—bristles with socioeconomic data, deep dives into long-term surveys of beliefs, and complex statistical tests. Lay readers who recall the scientific method chiefly from secondary school may be surprised to encounter the formal hypotheses in her journal articles, accompanied by explanations of data sources and analytical methods: social science as a science.

In that spirit, Gay often advanced evidence that called some tenet into question, and invited other academics to push their work further. For example, a 2004 American Political Science Review article on black Americans’ racial attitudes advanced a nuanced view of their circumstances. Most models suggested that black individuals’ views changed with rising economic and educational circumstances. But among other conclusions, Gay found that for blacks seeking access to a “more desirable” residential setting who are thwarted by residential segregation, “racially deterministic explanations of the social world” persist. Her wider view produced a more complex interpretation of citizens’ attitudes and politics—and an invitation to scholars to enhance their research by taking people’s contexts into account. Similarly, Hochschild, Gay, and other social scientists collaborated on a series of workshops, culminating in the 2013 book, Outsiders No More? Models of Immigrant Incorporation, that again stretched the field. Although sociologists and economists had studied immigrants’ adjustments to their new countries, Hochschild said, “Political scientists were slow on the uptake”—perhaps because participating in the “receptor country’s” public life is a second-generation transition. The workshops and book opened the door to much broader study of immigrants’ widening participation in American political life.

In these and other meticulous inquiries, Gay seemed to be pursuing at least two goals at once. She addressed topics that challenged scholarly assumptions, asking new questions and posing new ways of answering them (much as her mentors had challenged her in the 1990s, and as she challenged her students).

And she sought to understand groups’ motivations and beliefs in order to advance fuller participation in political life as a public good. Reflecting on her work, Gary King said Gay “always wants to have the big picture.” Scholarship involves keeping one’s head down, focused on detailed, in-depth inquiry, he continued—but with a large enough perspective “so you’re not putting your head down in the wrong direction.” Given the increasing connection between much research done across Harvard and the world beyond, he said, “She clearly understands that”—perhaps in part because Gay lived in different parts of the world early in life, and then stepped out of the academy briefly before recommitting to scholarship.

That may explain why Gay’s data analyses often seem to yield more rounded, complete portraits of people whose lives and beliefs had been reduced elsewhere in social science to a single characteristic. Academic though the 2013 book is, the research is built on a humane foundation. The editors dedicated their work “to migrants around the world who have the courage, imagination, and love for their families that enable or compel them to leave their home countries for another place that offers a chance…of a life with better material conditions, more political freedom, wider options for their children, and the opportunity to practice their religion or embody their culture as they wish.”

Bridget Terry Long, an economist who is past academic dean and now dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, regularly evaluates professors whose work is both academic and applicable to practice. She recently said Gay, whom she has known since before becoming dean in 2018, is “interested in research and discovery, but she also has interest in how that’s helping the world.” Combining the two, Long called her friend “the scholar’s scholar.”

Even though she always thought of herself as “an accidental academic leader,” given her dual interests it was perhaps inevitable that Gay began to assume a new role just 15 years into her fulfilling life as a professor. By her own account, “I loved being a part of this community” intellectually and “adored my students” at Harvard, who brought “a kind of vitality to my teaching and advising” she had not previously experienced. But she also viewed the service demands that accompany a professorship as satisfying opportunities (not a universal faculty perspective). As the government department’s director of graduate studies, for instance, she discovered that she liked “driving change at the system level”: scaling up what worked in her advising experiences, say, to “make advising work better, systematically” for colleagues and students.

“I liked being a generalist more than I anticipated,” she continued (at least in an academic setting, versus consulting). And she rediscovered the virtues of teamwork: “You get to know people best when you work with them on a project.” It was one thing to read Hochschild’s research, for example, but something richer to teach together, jointly engaging with the course content.

When FAS dean Michael D. Smith searched for a new social science dean in 2015, he said recently, Gay’s name bubbled up. They had not met previously, and their conversations about the disciplines, FAS’s mission, and prospective responses to challenges revealed “a real wisdom beyond her years,” he said. “There was just something about Claudine…that said we have to get her into the FAS leadership team.” And so he appointed her to oversee the largest cohort of professors: about 240 faculty members, one-third of FAS’s total—a job big enough, in short order, to preclude further teaching and research.

An FAS divisional dean delves into personnel matters: knowing each department, anticipating vacancies, planning appointments. Gay’s quantitative background was helpful in navigating the terrain, but Smith said she was, uniquely, adept at engaging historians and other qualitative scholars as well. He volunteered from observation the sense that when Gay approaches fields or issues she doesn’t know in depth, she asks (as he put it), “What can I learn from others that can help me make the institution better?”

Deans in fact often encounter such unknowns. Within the social sciences, Gay had to grapple with the first of several unaddressed cases of past sexual harassment or other misconduct, resulting initially in the March 2018 announcement by government professor Jorge Domínguez that he would retire from the faculty—and Smith’s decision to put him on administrative leave pending an investigation of the allegations. (That case and others spilled over into Gay’s next Harvard job.)

A very different experience arose in August 2017, when Gay and Long became acquainted through their appointment to the faculty advisory committee for the University’s presidential search: a chance to meet people from most Harvard schools, and to think about the institution as a whole. “We recognized in each other real curiosity about how such searches work, and getting Harvard the right person,” Long said. “She was a very thoughtful person, and she clearly was trying to understand the process and get the best outcome”—culminating in the election of President Bacow in February 2018. In turn, the committee members gained recognition of a similar sort: Long was appointed dean effective July 1; a few weeks later, Bacow made his first senior appointment as president, selecting Gay to succeed Smith in University Hall effective August 15.

Along with Tomiko Brown-Nagin, who became Radcliffe Institute dean that July 1, the cohort of new leaders found themselves “going through this transition at the same time—all learning together, talking together, trying to figure out how to do these jobs,” Long recalled. “Becoming a dean, you just can’t imagine the fire hose of information coming at you,” so consulting with similarly situated peers was helpful. There was a personal connection, too. Long and Gay have sons about the same age, and both new deans’ mothers required care. As professionals, mothers, and daughters, she and Gay were “dealing with jobs and families” simultaneously, resulting in “a kind of trust where I felt I could ask any question,” Long said, “and I hope she felt the same way.”

It is one thing to build that kind of trust one-on-one, and quite another to do so on the scale of a multi-thousand-person outfit like FAS. “I had a lot of experience being a student,” Gay said in describing her learning process. Assuming responsibility for a big new organization “is another opportunity to be a student”—to “learn from this collection of individuals. So let me go out and engage with them” on a “listening tour—it sounds cliché, but it’s so fundamental.” And having moved around the globe as a child, Gay said, “I’m used to navigating unfamiliar spaces” (perhaps in multiple senses). “I’m okay with feeling at two with my environment.” Go out she did, spawning admiring stories of the dean contacting people she wanted to meet, asking to visit their offices rather than summoning them to hers, and there learning about some new function over a cup of tea.

As dean in 2021, Gay said that engaging FAS colleagues in the pandemic response was the “model for how I want to tackle just about everything that’s hard.”

Photograph by Jim Harrison

As dean, Gay augmented financial aid, pushed hard to enhance tenure-track professors’ experiences and career prospects, and helped extend the faculty’s intellectual reach through searches for professors in new fields (ethnicity, indigeneity, and migration; climate and sustainability) and collaboration in President Bacow’s University initiatives that are anchored in FAS (quantum science; artificial intelligence; climate change).

Beyond those significant but not unprecedented acts, two kinds of crises elicited distinctive features of Gay’s leadership. The first required her to address a distressing number of cases of faculty members charged with unacceptable conduct. Following the formal review Dean Smith initiated, Gay announced in May 2019 that Domínguez would be stripped of his emeritus status, disinvited from FAS’s campus and activities (and ultimately, at her request, from the University campus and Harvard-sponsored events, too). In imposing “a set of sanctions that, in effect, removes Jorge Domínguez from our community” and explaining her decision, she used this case, and others, to create a common language about standards of conduct.

“I don’t relish the many opportunities I’ve had to communicate about these,” Gay said in 2021. Title IX processes, norms of behavior, and changes in culture, she insisted then, are “directly tied to our institutional ambition to be academically excellent. It’s not a side project.” Harvard, she continued, “doesn’t exist alongside society—it’s part of society,” so it is prey to some of the same failures and “the same kind of reckoning that’s happening in the broader culture.” Given the need to confront those realities, she found a way as dean to convey a message about inclusion as well: violators would be punished or removed from the scene in order to “ensure a safe and non-discriminatory educational and work environment” essential for the “well-being of our students, faculty, and staff.”

If resolving the harassment cases ultimately called for the dean’s singular voice, the COVID-19 pandemic necessarily embraced every member of the community. Gay engaged more than 100 FAS faculty colleagues, plus a couple dozen staff members, in task forces charged with every aspect of remote instruction, safety protocols, financial planning, and more. Emerging from the effort, in 2021, she characterized it as a “model for how I want to tackle just about everything that’s hard.” The collective effort revealed capabilities that neither she nor the people who exhibited them had fully recognized: in strategic thinking, acting quickly, and higher-level cooperation within FAS and across Harvard. A successor faculty group then examined the faculty’s financial prospects, in turn generating an FAS-wide strategic planning effort (still underway) to reimagine its intellectual aspirations, organization, graduate education, and other basic aspects of the research mission.

Abstract though that may sound, some participants describe the process as revolutionary. “Claudine did something very valuable and very important, which was to shift faculty involvement from the old model that all previous deans had used,” said John Y. Campbell. The Olshan professor of economics is a veteran of FAS financial oversight and planning during several prior deanships. His past service on the faculty’s Resources Committee, for instance, typically involved briefings by FAS financial staff members: “It encouraged a relatively superficial engagement,” he said, rather than actual faculty-shaped planning. In contrast, faculty and staff members of Gay’s pandemic planning teams “actually worked on things and developed ideas” together, he said. “This was huge.” Campbell and colleagues were then enlisted to consider multiyear budgeting—and ultimately delivered a new model that now informs all FAS financial decisions, consistent with its academic strategies.

Faculty governance “can’t work if faculty are just sitting back and criticizing,” Campbell said. Their detailed engagement in FAS operations and governance “has sort of been missing,” he continued. From the pandemic planning through the new financial modeling and now the encompassing strategic plan work, he said, Gay had found a way to effect that kind of involvement: “I give her a lot of credit for that.”

“She has the appeal to make you want to get on her team and make this work, to inspire the group to move forward.”

Of his experience overall, Campbell said, Gay “has a very appealing mixture of characteristics. She’s obviously a good listener.…She values input and process, but at a certain point, she says, ‘Now we need to move forward and make a decision.’” Finally, he said, “She has the appeal to make you want to get on her team and make this work, to inspire the group to move forward.”

One group that had the opportunity to see Dean Gay at work, and to be inspired to move forward, was the Harvard Corporation. By recent University standards, the announcement last December 15 that she had been elected president brought the search, begun five months earlier, to a swift conclusion, culminating her fast rise to the pinnacle of academic leadership.

The early decision gave Gay a longer transition to the president’s office. Because her FAS day job involved more extensive Harvard responsibilities than any predecessor since Derek Bok (elected from the Law School deanship, in 1971), this was no small benefit. She faced her widest listening tour yet, encompassing the professional schools, Harvard’s considerable presence in Allston and the Longwood Medical Area, and the higher-education and government communities beyond. Important appointments, for her successor (see here) and three other deans, loomed.

Whatever the challenges, Gay has had plenty of opportunities to hone her style of making decisions. “I tend to be a pretty decisive person,” she said in July, reflecting on such life choices as transferring from Princeton to Stanford, or pivoting from academia to consulting and back again. “Generally, I’m action-oriented. I like to get things done—to feel the sensation of progress.” Achieving that depends importantly on pragmatism, particularly in a community of diverse stakeholders, Gay acknowledged: “I hope that people describe me as collaborative. That’s always my instinct.”

That self-appraisal accords with the judgments of people who have worked alongside or observed Gay within the University (witness Campbell’s experience). After noting how prepared the new president is for meetings, Dean Long said, “Oftentimes, she isn’t trying to be the first person to speak, but she’s always very deliberative, honing in on the key issues of a new policy or decision.” In other words, the data-driven scholar is hungry for information, and focused in her inquiries. “At the same time,” Long concluded, echoing Mike Smith, “she always has the openness that her mind can be changed by new information. There’s a great deal she knows, but it’s obvious she is open to hearing what she doesn’t know.”

At a remove from that operational perspective, Gary King advanced a tag line to characterize his former student and department colleague. From student-scholar to academic administrator, he said, Gay had been “careful, thoughtful, decisive,” chopping his hands at each word for emphasis. Noting the inherently administrative nature of the presidency, he said, “It’s a political job” (a term held in favorable regard by political scientists). By temperament, training, and the nature of her scholarship, he said, “She’s a very astute politician, she’s a student of politicians.” From graduate school through the present, King said, “I have never ever seen her flustered.”

In part, that calm proceeds from a strong set of values underlying the work Gay does. Reflecting on her fellow teacher, Jennifer Hochschild said, “Still waters run deep”: Gay has “very strong views, which she does not express until relatively late in a decision-making process,” such as the work of FAS’s pandemic task forces, the faculty’s strategic planning, and the complex fact-finding and consultations involved in resolving misconduct cases. “She gathers information, sets up advisory and deliberative processes, and then when she’s comfortable, makes the decision she wants to make,” Hochschild said. “She’s very deliberative and consultative on the one hand, and then on the other, the buck stops here.”

What principles might apply as Gay organizes her administration? She lists three, beginning with a research university’s basic obligation: “I feel that places like Harvard, and Harvard more so than others, are really an anchor institution in democracy.” The University, she amplified, can never lose sight of that: “We wouldn’t exist if that society didn’t exist”—so it matters who is within the community, how they are taught, and how Harvard relates to other institutions. Second, “Harvard is so important in the lives of so many people,” from faculty and staff to students and alumni. Accordingly, she said, it must operate in a way that is seen and experienced as “reasonable, just, and ethical.” Finally, although the academy is inevitably “a hierarchical place” (with those who are tenured and others who are not), “I think hierarchy and a culture of respect can coexist,” she said—and the role of leadership is to make that so.

Interpreting those principles in light of her career to date, one might distill three values for Gay’s nascent presidency.

One is intellectual ambition—ignited as an undergraduate, deepened through demanding doctoral research, and reconfirmed by her decision to test her interests beyond the academy, and then to return. The “scholar’s scholar” loved being challenged by her advisers, and devoted herself to her graduate students in the same way. As director of graduate studies, social science dean, and FAS dean, she focused especially on the caliber of the faculty and their capacity to pursue demanding research: FAS’s strategic planning is centered above all on supporting research, graduate training, and means to advance interdisciplinary scholarship.

“The idea of the Ivory Tower is the past, not the future, of academia. We don’t exist outside of society, but as part of it.…Harvard has a duty…to be in service to the world.”

Another is impact. Both King and Long drew out that theme, and no wonder: Gay made a point of it in her remarks last December, when she said, “The idea of the Ivory Tower is the past, not the future, of academia. We don’t exist outside of society, but as part of it. And that means Harvard has a duty…to be in service to the world.” Through the questions Harvard scholars ask (she might have included some of her own), education, and public engagement, she said, “I see a university that is even more connected to the world.”

The last is inclusion: who is appointed to the faculty, who is admitted to study, and the conditions under which they work together. Gay’s life trajectory points in that direction. So does her research on political participation, inequality, and immigrant incorporation. So do her comments on hierarchy and respect. And so does her project, as FAS dean, of asking faculty members—all of them—to assume agency for planning their future as a preeminent educational institution together.

As Gay’s presidency begins, internal circumstances give her ample room to take the long view, just 13 years before Harvard’s four-hundredth anniversary. Financially, the place is in the pink of health, having enjoyed nearly a decade of operating surpluses. As she noted in a May decanal exit interview, those resources are “empowering,” so even FAS, which has kept a tight belt, can “take some risks” intellectually. Gay is an effective fundraiser (witness the gifts secured for undergraduate financial aid) and will likely conduct a major fundraising drive. But she is under no near-term pressure to proceed, and so can devote scarce time now to articulating priorities worthy of future support. With construction begun on the enterprise research campus (see here) and other projects pending, she need not focus as much energy on Allston development as Faust and Bacow did.

One part of the new president’s “listening tour” was a Longwood-Allston-Harvard Yard ice cream social, to meet students, staff, and faculty, on July 11.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

The external environment, however, affords no such leisure. On June 29, less than 48 hours before the Bacow administration gave way to hers, the Supreme Court threw out the admissions procedures that Harvard has used to admit a racially diverse student body (see here). On July 11, amid relentless political criticism of higher education, a Gallup poll revealed record-low public confidence in the sector. If anything, Gay holds the most visible university presidency in the country under circumstances even more alarming for education than those that concerned the Corporation and Bacow in early 2018.

As summer settled humidly on Massachusetts in early July, the University’s thirtieth president seemed unflustered by what lay ahead. She modeled her commitment to reaching out to people where they are, hosting community ice cream socials across campus on July 11, in Longwood, at the Business School, and in Harvard Yard—not just in Cambridge. In the weeks before the opening of the new academic year and the installation exercises on September 29, she would have more opportunities to take stock of the sprawling institution she leads. After a protracted recovery from a long period of financial constraint, the relief that followed the pandemic, and now a transition in Mass Hall, the community appears ready for an intellectually ambitious agenda. In Claudine Gay, Harvard would seem to have the leader for that moment.