In 1831, the abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Maria W. Stewart lived within Boston’s small but vibrant Beacon Hill community of free blacks who had come to view the city as something of a haven. American abolitionism was gaining momentum, and Stewart published a fiery essay in the anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator. “How long,” she asked, “shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles? Unite and build a store of your own…possess the spirit of independence. The Americans do, and why should not you?”

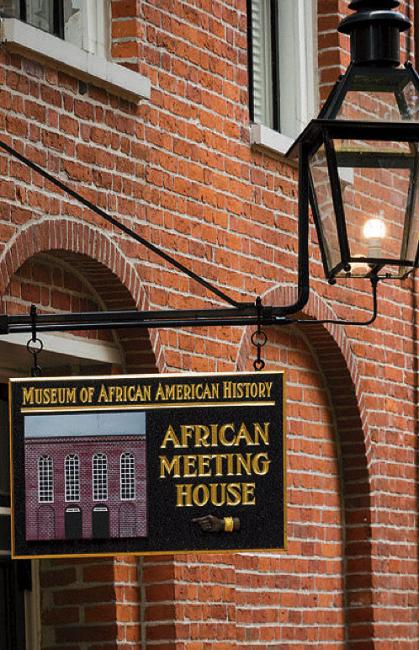

At the time, such radicalism was rarely openly espoused in the United States—but was not unusual at the African Meeting House, a Beacon Hill sanctuary and font of activism. It hosted speakers like Stewart, Frederick Douglass, and the journalist and historian William Cooper Nell, among many others, both black and white. The building—now part of the Museum of African American History in Boston and Nantucket—was constructed in 1806 by black residents of Beacon Hill’s North Slope. And for nearly a century, during the formative time in American history leading up to and through the Civil War, the site served as a house of worship, an educational center, and the locus of news reports from afar. It was also the main forum for discussions and debates over critical social and political issues of the day, where people came to organize support for abolition, women’s and voting rights, and equality in education.

left: Courtesy of Shawmut Design and Construction, Boston | Nantucket; Right: by Randy duchaine/alamy stock photo

During a museum tour, visitors can see the restored interior of the meeting house and sit in the pews or stand in the pulpit to imagine a previous era’s impassioned discussions and arguments about how to generate social change. “Here, in this place, was where this black community, alongside their friends and allies, could talk about anything they wanted without being shut down,” museum site manager Tobias Major, A.L.M. ’14, told a recent group of visitors. “Some of the incredible stuff these men and women did here, especially politically speaking, was light years ahead of other parts of the country.”

Construction of the brick building on a short block off Joy Street was led by Reverend Thomas Paul, a free black man from New Hampshire who had moved to Boston with his wife and children. Initially a member of the First Baptist Church, he responded to conflicts over lowly treatment of black parishioners by founding the First African Baptist Church, housing it at the new meeting house. He was a well-educated abolitionist and presided until 1829, setting the tone for spiritually based political action, according to Major. Instead of using censored versions of the Good Book provided by many slave masters, with stories of uprisings and equality among God’s creatures expurgated, “here, in this building, Reverend Paul could freely and as loudly as he wanted to preach from the Book of Exodus,” Major told the group, “which is the story of people escaping slavery.”

It wasn’t always so. Slavery was legalized in Massachusetts a few years after the first documented black people arrived in Boston on the slave ship Desiré in 1638. Landmark lawsuits brought by two slaves ended the practice in Massachusetts in 1783, Major explained. By then, a core group of free black people had already founded pivotal organizations, like the first African American fraternal order, now called the Prince Hall Freemasonry, and the African Society for Mutual Aid and Charity (which offered social services, financial help, and job opportunities).

By 1800, about 1,100 black people lived in Boston, most on the North Slope of Beacon Hill, within the streets around the future meeting house. The neighborhood had clothing stores, barbershops, and other businesses in what “was like a city within a city,” Major noted. Residents included the leaders who founded the anti-slavery Massachusetts General Colored Association in 1826 (headquartered at the meeting house), and a group of galvanized women who established the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, among other pioneering equal-rights organizations.

As the nationwide abolitionist movement grew, the meeting house hosted prominent speakers, including David Walker. “Walker was like the Malcolm X of the 1800s” who addressed crowds at the meeting house even when his written work was banned elsewhere, Major said. “His manifesto, Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World in 1829, essentially told people, ‘Hey, if you want to be treated equally, you have to get out there and fight for it.’ And for some people that was a dangerous call to action.”

Also welcomed were white abolitionists and rights advocates, like Sarah and Angelina Grimke, Harvard-trained lawyer Wendell Phillips, A.B. 1831, LL.B. 1834, and William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison founded and ran The Liberator, a weekly newspaper printed in downtown Boston: from 1831 to 1865 it was the most important outlet for promoting the cause of freedom, along with other political reforms. Garrison also cofounded the influential New England Anti-Slavery Society at the meeting house in 1832, and that same year gave a speech there on “Progress of the Abolition Cause.” “Last year I felt as if I were fighting single-handed against the great enemy,” he told the audience. “Now I see around me a host of valiant warriors, armed with weapons of an immortal temper, whom nothing can daunt, and who are pledged to the end of the contest.”

The antebellum black residents of the North Slope were wholly engaged in the fight for liberation, says museum president and CEO Noelle Trent, from promoting speakers and education for all to protesting the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, harboring people on the Underground Railroad, and even staging rescues of freedom-seekers captured in Boston. “If you are doing anything for abolition, you are not someone until you come to Boston,” Trent notes, “and the space that legitimized you and your work was the African Meeting House.”

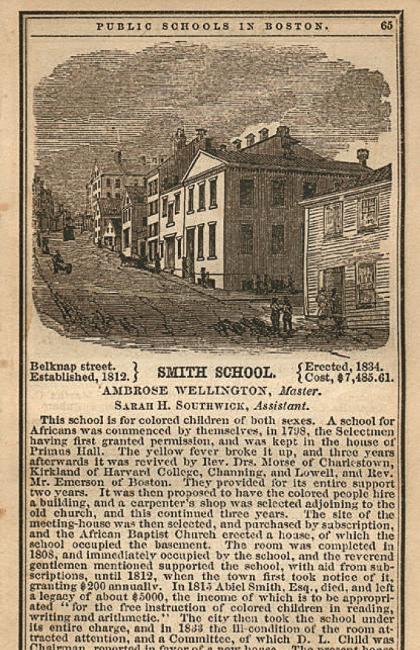

Tours focus on the meeting house, but the museum also encompasses the adjacent Abiel Smith School (along with two Nantucket properties: the circa 1824 African Meeting House and 1774 Boston-Higgenbotham House, reflecting the historic African American populations on the island, are open seasonally). Named for its white abolitionist funder, and built by the city of Boston in 1835, the school was erected to serve solely as a public school for black students. But in the ensuing years, it became the locus of arguments over separate and unequal education. Ultimately, many (including a vociferous William Cooper Nell) protested segregation, with some moving their children back to meeting house classrooms, where a school had previously operated from 1808 to 1835, and the Smith school was closed. That fight also led to the state legislature’s action to desegregate public schools in 1855.

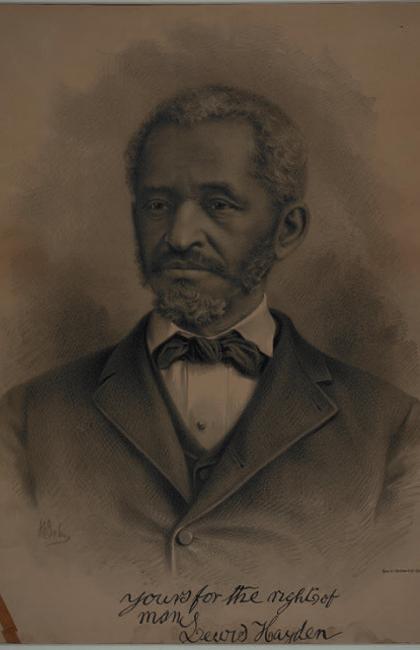

Little of the original interior of the school remains; it now houses the museum’s visitor center and galleries. This winter’s exhibition, “The Emancipation Proclamation: A Pragmatic Compromise,” explores the impact of the 1863 document that freed enslaved people in the Confederacy, allowed blacks to join the military, and changed the course of the Civil War. Documents and photographs reflect the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry Regiment, for which the meeting house served as a recruitment center for soldiers. (It was also a forum for Douglass’s impassioned lobbying for the cause. Two of his sons were among the first to enlist.) Books on display include William Cooper Nell’s The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, the first published military history by an African American, and The Narrative of the Life and Travels of Mrs. Nancy Prince—in which Prince recounts her nine years in Russia and return to Boston and activism. A display shows mastheads of The Liberator and the newspaper’s “imposing stone” (a slate and pine stand on which Garrison composed type). There are portraits of abolitionist leaders, like Wendell Phillips, who worked for equality until the Fifteenth Amendment, granting voting rights to black men, was ratified in 1870. Another depicts Lewis Hayden who, with his wife Harriet, escaped slavery in Kentucky and settled in Boston in 1848, where they became instrumental to the community and its causes. A clothing store and boarding house owner who later became a state representative, Lewis helped fund John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, and both Haydens sheltered people in the Underground Railroad at their 66 Phillips Street home (further catalyzed by The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850). They reportedly kept kegs of gunpowder in the basement to ward off slave catchers.

Visitors are free to roam the exhibit then head next door with a guide to the African Meeting House (also historically known as the Belknap Street Church). Restored to circa 1855, the sanctuary’s interior, painted off-white, holds a symmetrical set of curved pews separated by an aisle, along with a wraparound balcony: both face a modest pulpit. There are no stained-glass windows, sculptures, or religious ornamentation. The space is Quakerly in its simplicity, and light pours in through windows. “This was a community like any other, made up of different personalities, opinions, perspectives,” Major explains. “There were back- and-forth conversations and heated debate, almost like watching public access city hall today.” The open forum allowed both men and women “a place to be themselves and really get their voices out there. You can imagine that the conversations that happened here led to good changes in our society.”

Imagine people crowding in to hear the latest speaker: someone talking about what he saw in the battles of Bleeding Kansas or witnessed in the South since the Proclamation. “To hear the news then was not even about getting a newspaper,” Trent points out. “You had to wait until someone who witnessed it came to tell you what happened.” For her, the meeting house is “more than the words spoken there, it’s the spirit that exists in the space, the work done by individuals,” she adds. “I truly believe you can feel it when you stand in the pulpit. I could understand what people must have felt coming in from the cold—you had to be dedicated to schlep up that hill. And there are stories sometimes of it being so packed-in that people were standing outside because they had to hear someone, and they had to contribute.”

Here they would also have heard about the slavecatchers invading homes on Beacon Hill—coming to the church, hunting for people to take back to the South. Parishioners met, too, to plan rescues or protests. Importantly, Trent notes, these endeavors were undertaken by common people. The meeting house “was sustained in its heyday by the community,” she says. “Don’t get me wrong, I love Frederick Douglass and I did my dissertation on him. But it’s the people we don’t know, who worked in the shipyard and cleaning the mayor’s home, who supported anti-slavery with the very little disposable income and time they had.”

For example, members of The New England Freedom Association, co-founded by Nell, gathered at the meeting house. He wrote about a session there in 1845: “The object of our association is to extend a helping hand to all who may bid adieu to whips and chains, and by the welcome light of the North Star, reach a haven where they can be protected from the grasp of the man-stealer,” according to the U.S. National Park Service website.

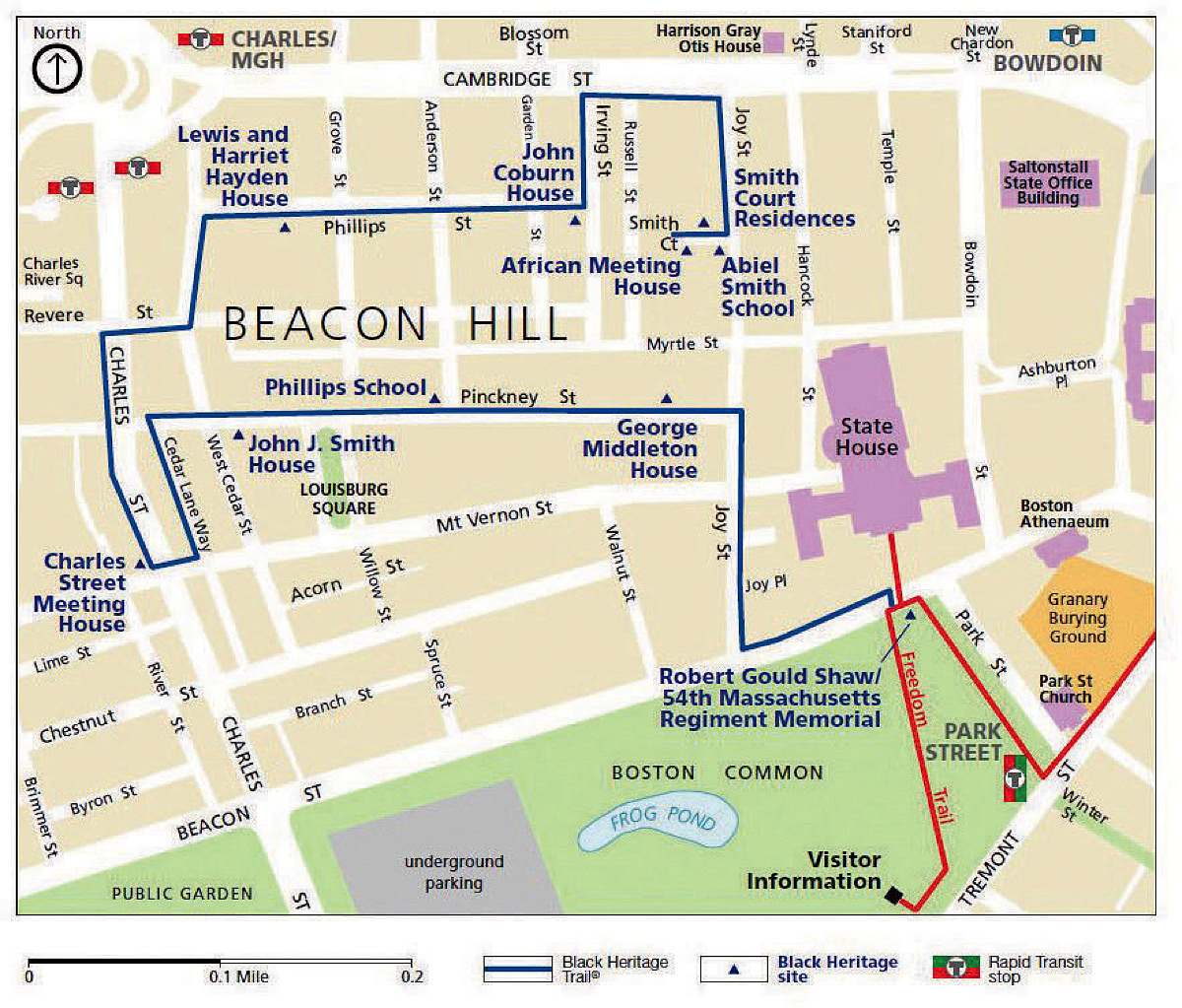

The museum, which owns the two historic buildings—the meeting house and Abiel Smith School—operates them in conjunction with the National Park Service, as part of the larger Boston African American National Historic Site. To explore the work and experiences of Beacon Hill’s antebellum black community more fully, the museum developed the 1.5-mile Black Heritage Trail. It highlights 10 sites, ending at the museum (which has the only buildings open to the public). The Park Service offers ranger-led trail tours from late May through October, but anyone can take the self-guided version, using the online audio program, any time.

The trail begins at the Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regimental Memorial in Boston Common, the tribute to the black soldiers and their commander. Shaw, the son of well-known white abolitionists, attended Harvard in the latter 1850s but did not graduate; he took command of the 54th Regiment at the age of 25 and was killed in battle the same year.

The trail also stops in front of the Phillips Street homes of the Haydens and another clothier and activist named John Coburn. In 1851, after fugitive slave Shadrach Minkins was covertly rescued from the courthouse by black Bostonians who facilitated his journey to Canada, Coburn was arrested, tried, and acquitted for his alleged involvement. As the trail winds toward the museum, it highlights several Smith Court homes adjacent to the meeting house, including the rowhouse where William Cooper Nell lived for a time.

The community there was active through the Civil War, but in its wake, black residents began moving to the city’s South End. Immigrants also were increasingly settling in Beacon Hill. The Baptist congregation at the meeting house relocated its church to the South End too, selling the meeting house in 1898. Six years later, The Jewish Congregation of Anshi Libavitz moved into the building, which remained a synagogue until shortly before it was sold to the museum in 1972. For museum visitors now, the Black Heritage Trail, museum tours, and exhibited photographs and other artifacts illuminate “the powerful work that happened here,” Major says, and “we are still feeling the effects of that today.”