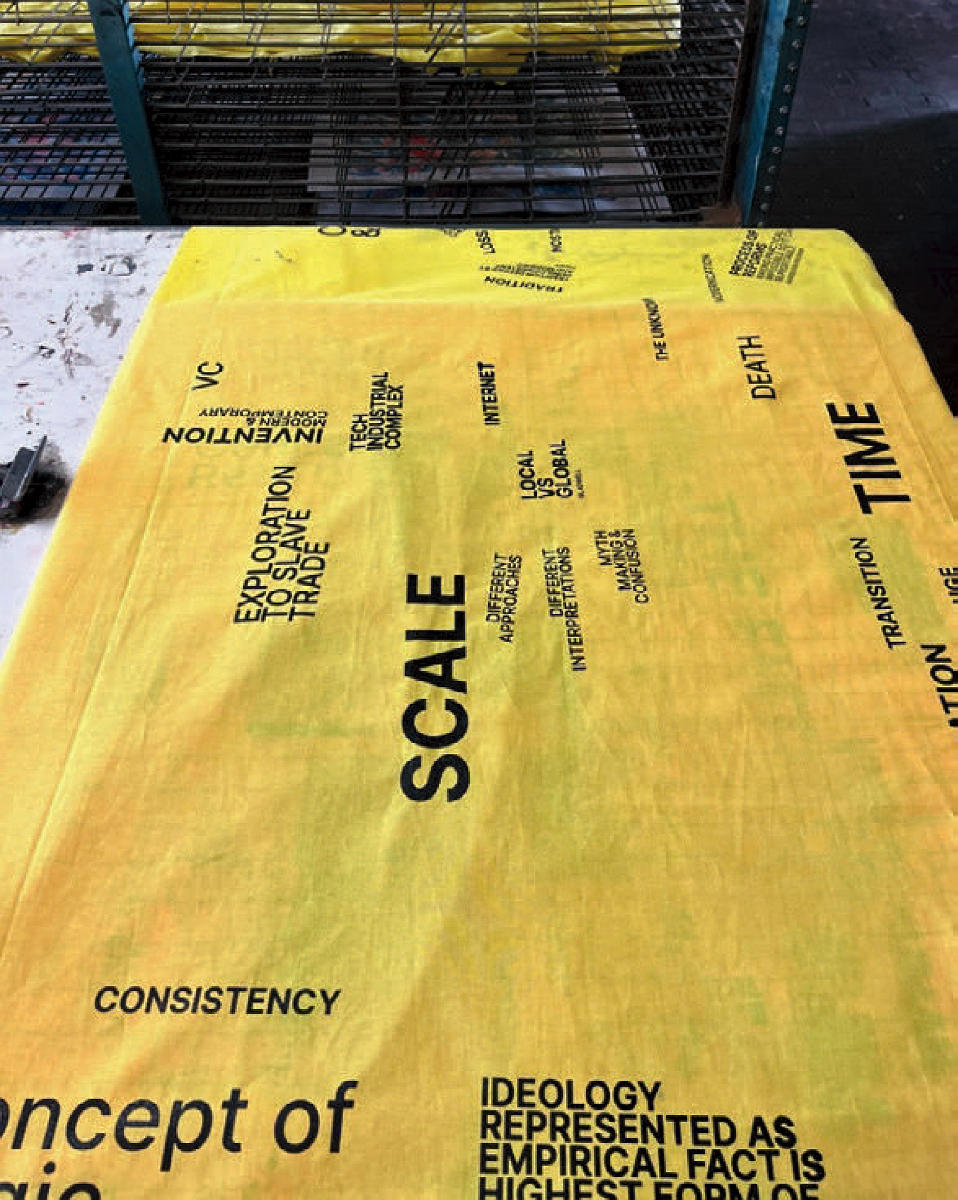

Amy Yoshitsu ’10 has been working on a mind map, a document that resembles a street map representing math, dreams, and a spreadsheet of the economic and social resources that go into the art she creates. Main arteries labeled “Systems,” “Racism,” and “The Future” intersect with smaller boulevards demarcating “Patriarchy,” “Space,” and “Concept of Reality,” with tiny side streets labeled “Climate Crisis,” “Emancipatory Politics” and “Making Impossible Seem Possible.”

Eventually, Yoshitsu will silkscreen the map onto three queen-sized bed duvet covers, materials that represent themes of cost and inequality: how fundamental the need for sleep is, in contrast to how expensive beds and bedding can be; and the number of unhoused people in Berkeley, where she grew up and works today.

Yoshitsu explores racism, patriarchy, capitalism, and infrastructure in various forms of media, often using repurposed materials, hand-stitching together recycled single-use plastic scraps or photos to create sculptures that she hangs from the ceiling or orients in a public place to be photographed again. Her work is also inspired by information Yoshitsu absorbed as a child, from learning about family members detained in internment camps for Japanese people during WWII to her father quizzing her on how much she thought things cost and what she thought about the concept of money. She remembers being very excited when she learned the word “socio-economic.” It helped her make sense of Berkeley’s diverse environment. “Even though there was definitely hierarchy and segregation there, it was the 90s, the peak of the mixing pot ideology.”

Currently, Yoshitsu is at work on a large-scale installation project called “Inherited and Remade,” a four-foot-tall soft sculpture accompanied by phrases and sentences related to themes ranging from environmental issues, her upbringing as a child of two working artists, and inherited “f----- up systems.” Much of her work makes the viewer look twice; recognizable images and words look different at a second glance. A giant photo collage balancing on power lines could be ominous or humorous, or both, creating an unsettled feeling.

Yoshitsu’s current artistic media range from 3-D printing to carved-up photo prints (she goes through hundreds of X-Acto knives). But silkscreen is where she began. She entered the College as a math major, until an introductory silkscreen class with artist and senior lecturer Annette Lemieux changed her course. Her first piece, called “Under Control,” made of mirror glass and aluminum, was inspired by an article she’d read, explaining that it cost the same amount to incarcerate a person as it did to pay tuition and board for a student at Harvard: “This immediately sent me down the path of the themes of my artwork.”

Her curiosity about systems—and her desire to improve them—carry into her day job at Converge Collaborative, a Berkeley-based multimedia workers’ co-op and arts collective she co-founded in 2020 with some friends, including former Harvard roommate Vi Vu ’10, M.L.A. ’15. They began Converge with the question, “How can [we] bring some more autonomy that allows one to be creative while also being able to earn money and have social and economic support towards their lives and their work?” The six-person team provides services like marketing, branding, software and web design, and videography to independent, corporate, nonprofit, and governmental clients.

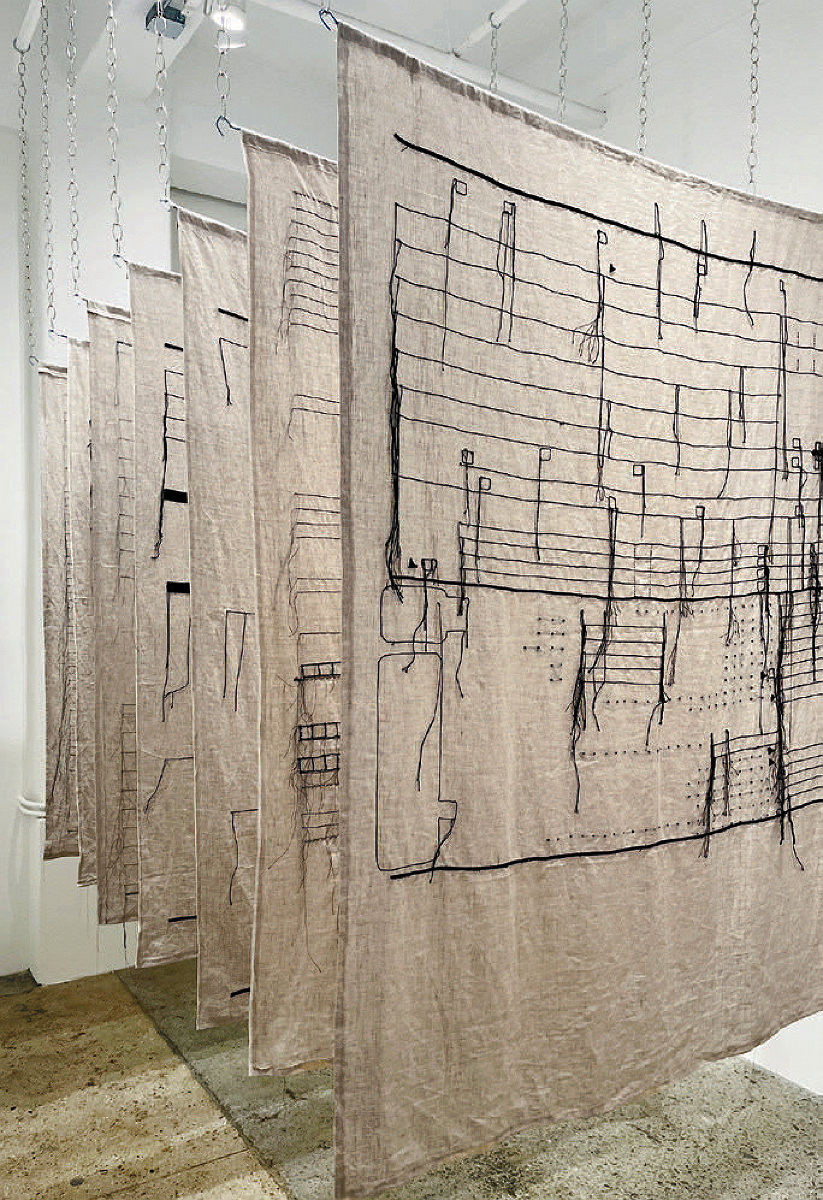

Yoshitsu’s dual roles as business owner and artist inform each other. She handles many of the insurance, tax, and legal necessities at Converge, which helped inspire one of her pieces at “Hedges and Ledgers,” her spring 2023 solo exhibition at Satchel Projects, a New York gallery. The artwork featured linen fabric stitched with lines from a 1040 income tax form enlarged to the scale of the human body. Sometimes the overlap is more indirect. During a residency at the scenic Esalen Institute in Big Sur, she interviewed the grounds staff about their work and lives—Converge produces a work/life podcast called “Bring Your Full Self.” And she recently spent part of an artist’s residency in Vermont working on Converge bylaws to become an official worker’s cooperative in California.

It took Yoshitsu some time to find her artistic community at Harvard. “I felt somewhat alienated from the rest of the environment,” she says. “Even though I had experienced things like patriarchy, capitalism, and white supremacy in an implicit way, I really understood it when I went to Harvard.” She felt more at home in the Boston punk scene, and remembers screwing up the nerve to talk to some punks in Harvard Square. “Being part of a community outside of the bubble was really helpful for me.”

Constantly ruminating on social structures, inequality, and the environment may seem taxing, but Yoshitsu makes sense of it through her art. “It’s a path towards healing,” she says. “That is why I make the work that I do: to understand my relationships, to understand myself.”

Sewing, in particular, helps bring the pieces of her life together. Her grandmother was a seamstress, and Yoshitsu’s mother taught her to sew when she was a child. “In a lot of my work, there’s repetition,” she says. “Doing these rote hand things, it’s a meditative physical process.” In addition to hand-sewing the bedsheets in “Hedges and Ledgers,” she stitches together images for her photo sculptures: after traveling the world to take photographs, she color-corrects them before sending them to a local printer. “Then they’re all on a table, and I start cutting, and that cutting process takes six months at least.” Once she has enough pieces, she sorts them into piles of aesthetic harmonies. “And then I start sewing them together,” using plain black thread and a heavy-duty Singer sewing machine, until the physical size of the sculpture requires her to finish sewing by hand, weaving together a sculpture that seems like part Möbius strip, part traffic accident, part portal, part carcass on a meat hook.

She never knows what the finished product will look like until it becomes so large and unwieldy that it can’t hold itself up anymore—and when her intuition tells her it is complete. “I know what ‘done’ looks like,” she says. “I have a lot of rules for myself. I know what controlled chaos looks like.”