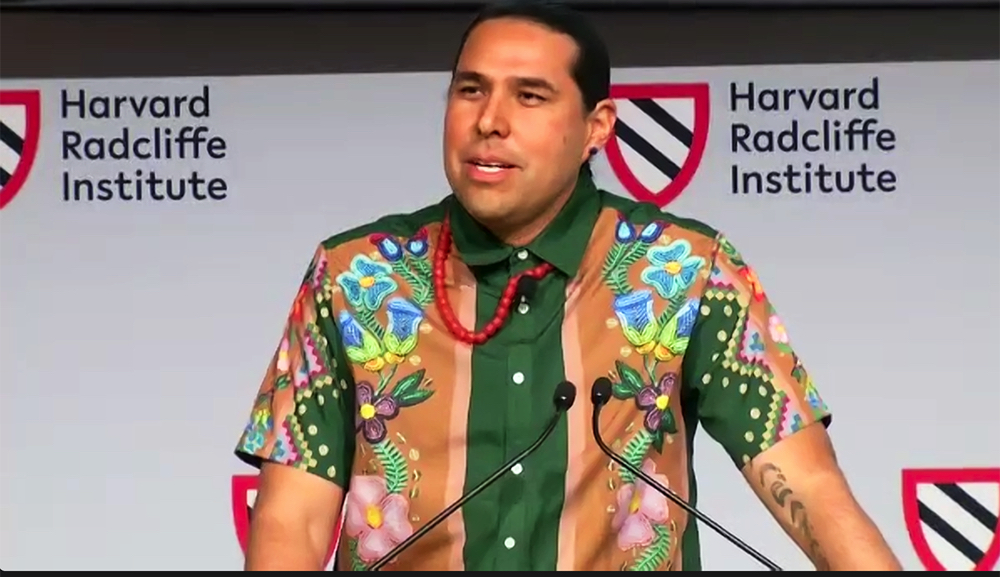

At a Radcliffe Institute conference intended to launch the process of making amends for Harvard’s long history of injustice against indigenous communities—detailed in a 2022 University report—the biggest agenda item wasn’t listed in the official program: it was the fact that Harvard continues to hold the remains of thousands of Native Americans in its museum collections. In his keynote address, comedian, writer, and activist Dallas Goldtooth, a member of the Mdewakanton Dakota and Diné tribes, marveled, “Y’all had the audacity to do a report and name a whole conference ‘Legacies of Indigenous Enslavement and Indenture,’ and you’ve still got bodies in the building?”

The gathering, held Nov 2-3, was prompted by one of the recommendations in the report on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery: that the University “honor, engage, and support Native communities,” in part by organizing a conference on indigenous slavery and colonialism. Scholars and Native American leaders discussed the early history of indigenous enslavement in the Americas and New England, and the devastating, persistent effects of dispossession and cultural annihilation. Representatives from other universities—UCLA, Stanford, the University of British Columbia—described the ways their institutions have built relationships with tribes in their local areas. Harvard administrators, including President Claudine Gay, Provost Alan Garber, and Radcliffe dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin, acknowledged the University’s harmful past. “Much of this history is appalling, painful, and shameful,” said conference co-organizer Joseph P. Gone in his opening remarks. A professor of anthropology and of global health and social medicine, he is also one of a small number of Harvard faculty members and graduate students who come from indigenous backgrounds (several others also spoke at the conference). A member of the Aaniiih-Gros Ventre tribal nation of Montana, Gone directs the Harvard University Native American Program. The institution’s past interaction with indigenous communities, he said, “is replete with exploitation and mistreatment of the powerless by the powerful.”

The ”Bodies in the Building”

But speaker after speaker returned to the issue of Harvard’s contemporary conduct and those “bodies in the building,” as Goldtooth had put it. A cofounder of the indigenous sketch comedy troupe The 1491s and an actor in the acclaimed television series Reservation Dogs (which he also co-wrote) and Rutherford Falls, Goldtooth spoke to a sold-out crowd, including many indigenous listeners, on Thursday evening. Discussing the question of accountability and the power of collective action, he said, “Harvard cannot undo the harm of the past until it stops the harm that it is doing today.” He told the audience that as soon as his participation in the conference was announced, “I got seven messages from tribal representatives, saying, ‘Hey, you’re going to Harvard? Well, we’re trying to get remains back to our communities. Can you say something?’ And so, this is me, saying something.”

Often, the outrage and pain were palpable. Faries Gray, sagamore of the Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag, delivered a prayer that he warned the audience would be “more like medicine for Harvard.” And he was right. The University’s campus sits on his tribe’s ancestral land, and speaking through clenched teeth, he described how Harvard was “at the core” of the centuries of loss and destruction his people had endured. He said that when he was first invited to the conference, he didn’t want to go. He changed his mind, in part to bring a message: “I pray that Harvard can return our remains to us,” he said. “I pray that Harvard can return our burial items. They have one of our long bows, an original long bow that they have in a box somewhere….What gives Harvard the right for this? To just keep it like we’re not here.”

In her remarks, Gay reiterated an assertion she made last December, when she was still dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, that “Native American ancestors should not be in our collections.” Since then, she said, she has doubled the size of the office that is working to expedite their return. The repatriation of human remains, burial objects, and sacred items is required by law, under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Enacted in 1990, it gave institutions five years to inventory their collections, in consultation with tribes, and then to return them. But more than 30 years later, Harvard still retains more than half of its collection, primarily in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (see a full examination of the issue at “Repatriating Native American Remains”). According to an April report by ProPublica, the University—one of about 200 institutions out of compliance with NAGPRA—has the fourth largest collection of unrepatriated remains. ProPublica found that Harvard had made available for return only 38 percent of the more than 10,000 human remains it reported to the federal government, and 29 percent of the more than 18,500 funerary objects. A Harvard Gazette update from late October states that in recent months, the University has returned the remains of an additional 500 individuals (for a cumulative total of 4,347), and an additional 4,600 funerary objects (for a total of 10,016).

At the conference, Gay said, “The Peabody Museum is committed to partnering with U.S. tribal nations and honoring tribal timelines to complete the transfer of legal authority, control, and decisions about all ancestors and their funerary belongings—and to do so over the next three years under NAGPRA legislation.” She added, “To ensure that there’s real progress on this, I’ve requested quarterly updates to make sure that this continues to move apace.”

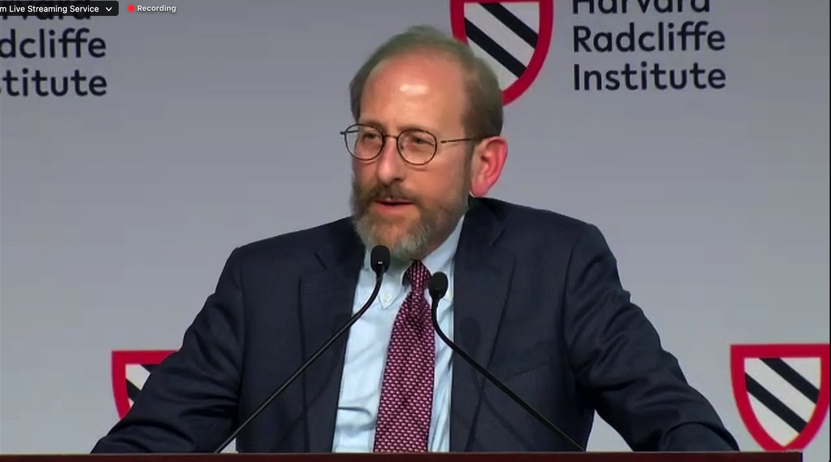

Later, Garber echoed her pledge: “We realize there are these open wounds,” he said. “We are committed to getting this done expeditiously. We’ve apologized before, and I’ll repeat it, for the fact that this is not already behind us. That must occur. That must occur quickly. And we are committed to doing that.”

Calling the conference “an opportunity for listening and learning,” Gay said, “I hope that Harvard can forge new relationships with communities that have been harmed by the University’s past actions.”

The Unfulfilled Promise to Teach Indigenous Students

Judging by the comments of other indigenous speakers, including some with longstanding ties to the University, it remains to be seen whether those new relationships will materialize. Tobias J. Vanderhoop, M.P.A. ’08, former tribal chairman of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), on Martha’s Vineyard, reminded Harvard of its unfulfilled promise to teach indigenous students. “Look back to your charter,” he admonished. The University’s founding document from 1650 committed it to “the education of the English and Indian youth.” (This commitment was not exactly benevolent: the underlying purpose in educating Native Americans at that time was to “civilize” them and strip away their existing culture, religion, and language. But Vanderhoop noted that some indigenous people managed to turn education into a tool for understanding and resisting the new laws that colonial governments were using against them: “an arrow in the quiver to fight.”)

Harvard’s Indian College was constructed in 1655, but it only ever enrolled five Native students, and only one, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, A.B. 1665, actually graduated. (Another, Joel Jacobs, completed the requirements for a degree, but died before he could receive it.) By 1670, the Indian College building had been given over to the College’s printing press, and by the 1690s it was demolished. Recalling this history, Vanderhoop said, “Make good with the relationship you’re supposed to have with the tribal nations, especially all of us that are from New England, all of us that are from this very land that the institution stands upon. Make it so that I don’t have to say I’m the first man from my community in over 300 years that came through this place; make it so that I can talk about the parade of my people coming through this institution.”

“Who Is This Conference For?”

In what turned out to be a bracing final panel discussion focused on “Harvard and Massachusetts Tribal Repair,” speakers wondered aloud whether last week’s gathering should have been held at all. “I think this conference is incredibly premature,” said Elizabeth Solomon ’79, A.L.M. ’20, director of administration at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and a council member for the Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag (as well as a speaker at Gay’s installation exercises September 29). “My understanding of this conference was that it was going to be about Harvard’s role in colonization and dispossession and cultural genocide,” she said, “but in fact, we’ve heard very little about Harvard.”

Observing that much of the programmed discussion that did concern Harvard had focused on the colonial era rather than the present, and that the bulk of the day’s speakers and moderators were academics rather than tribal representatives, she asked, “Who is this conference for? I would argue it’s not for our communities.” The event’s themes, “responsibility,” and “repair,” she said, were skipping a step: “truth.” “Harvard has been complicit and continues to be complicit in the harms of colonization,” she said. “We’re not ready for that repair. There needs to be a building of relationships first, because Harvard does not have a relationship with the local communities here. And most individuals from the local communities do not have a relationship with Harvard.”

“So that’s where it needs to start,” she continued—not with a public conference, but with “Harvard internally,” establishing clarity about its past and continuing responsibility. “And then it needs to continue with building reciprocal, meaningful relationships with indigenous communities. And only then can we talk about repair.”

Lydia Curliss, a Hassanamisco Nipmuc Band council member, added, “Accountability is about more than naming past harms. It’s about moving forward with considerations of communities and centering their needs. It also means being in good relation.” A doctoral student in information studies at the University of Maryland, Curliss grew up in Cambridge, and she remembered spending time on Harvard’s campus and in its museums: “It wasn’t until much later that I realized that these spaces were haunted.” Referencing the indigenous remains still in University hands, she said, “There has been little real effort to build the relationships necessary to repair.”

The discussion carried on that way for an hour and a half. David Weeden, tribal historic preservation officer and tribal councilman for the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, said, “Harvard has a lot of resources, and they need to reach out to the communities. Don’t sit back and let academics think, ‘I know what’s good for you’—come talk to us and ask us what we need. There’s a need for economic development; there’s a need for self-governance training; we need anthropologists to tell our own stories. It gets tiring to hear academics telling our story for us, because they lacked the cultural insight to be able to tell it correctly.”

There were stifled gasps from the audience when Cheryl Andrews-Maltais, chairwoman of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), said of the University’s Legacy of Slavery report, “What was astounding to us…is the lack of any Native presence in the work that was done.” The faculty committee that researched and produced the report did not include any indigenous members. “I say it all the time: people love to write about us, but they don’t talk to us. So how can you get what the impact was? And what the long- and short-term historic trauma and the deconstruction of our communities and our way of life was, without speaking to us? We had a lot of academics listed [among the report’s authors], but we didn’t have any Indians?”

Andrews-Maltais told the audience that five months after the report’s release, she sent a letter she sent to former President Lawrence Bacow’s office, listing her tribal council’s recommendations for reparative actions the University could take. She never received a response, she said, but many of her suggested actions remain relevant: scholarships for Massachusetts tribe members, and robust curricula and support in the Law School and the Kennedy School for students interested in tribal rights and public policy. Andrews-Maltais’s daughter, Samantha Maltais, is a third-year law student at Harvard and the first from her tribe to attend the Law School; speaking of the need for the University to establish relationships with local tribes and “formally recognize Harvard’s responsibility to us,” Andrews-Maltais added, “My daughter is here because she could envision that. I could not.”

Her family’s tribe, the Aquinnah, was also the home of Cheeshahteaumuck and Jacobs, the two seventeenth-century indigenous students, and she said that although Harvard frequently invokes their names in documents like the slavery report, the community itself remains largely overlooked. “So, I would like to see Harvard step up and take the actions it promised with regard to indigenous people….and with regard to the hope that what we’ve been here to do for the past two days is really a sincere attempt to heal the pain.”

Afterward, Garber searched for the words to respond. “I often feel humble, and I often say that, but I never mean it like I do right now,” he said. “I want to thank all of you for being here, because I know that we at Harvard are the beneficiaries of this meeting, and that we are the ones who are doing the learning.”

In his own closing remarks, Gone acknowledged, “I know that we did receive strong medicine today.” But he also added, “We had University decision-makers”—Gay, Garber, Brown-Nagin—“attending to a gathering of indigenous representatives and tribal delegates to speak their truth in ways that I actually have not witnessed in my time at Harvard.” (Gone first arrived in 1988 as a College freshman.) And despite how strong the medicine was, he said, he hoped it was “the beginning of something.”