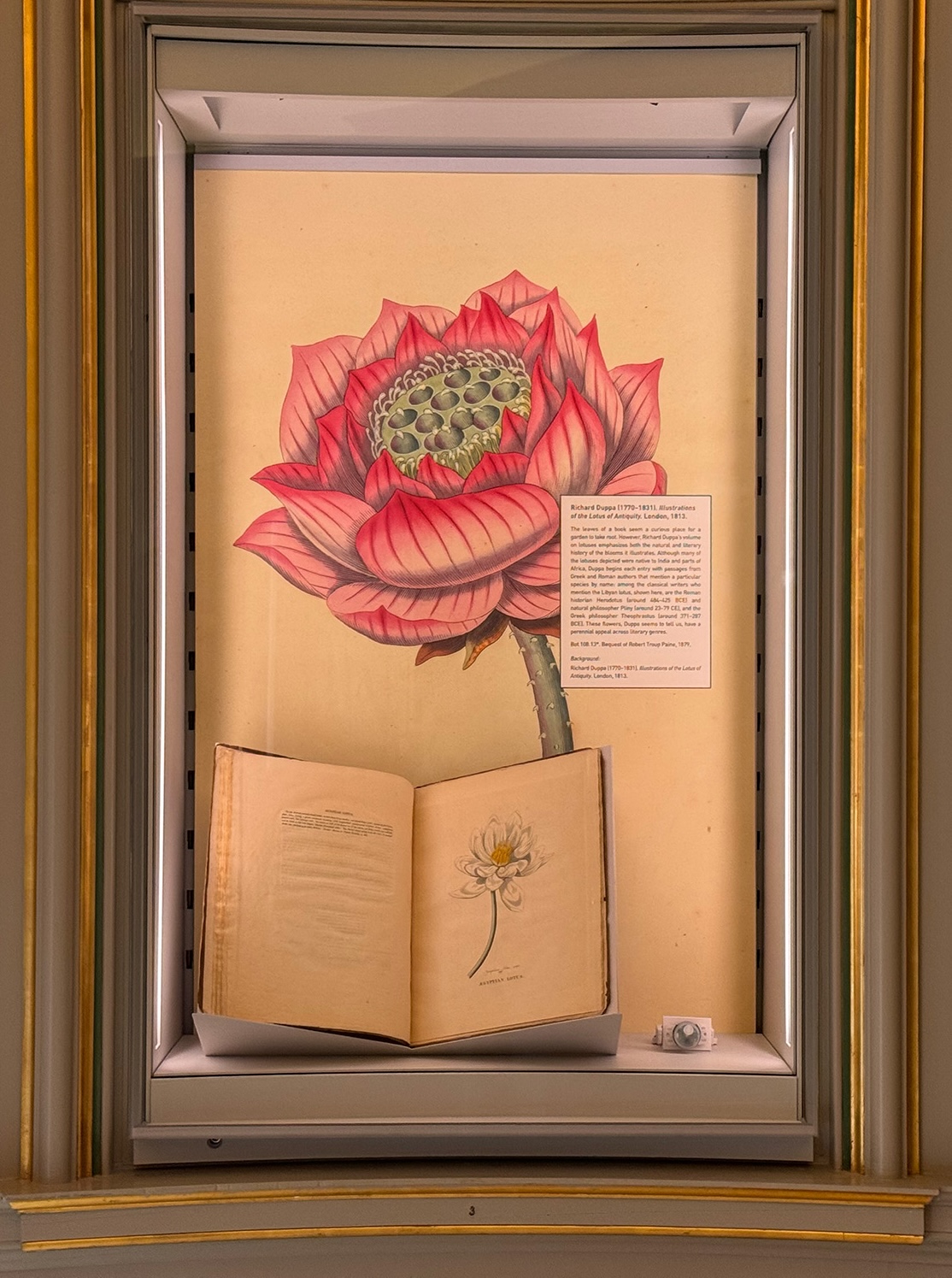

Curators at Houghton Library are bringing a splash of green and other vibrant color to the building’s main lobby this summer with a new exhibition of rare and old botanical illustrations.

Though visitors from the public were not able to enter Harvard Yard during much of the spring because of campus protests and turmoil, Houghton staff have continued staging original exhibits for the renovated building’s showcases, highlighting in this instance colorful and centuries-old volumes of painstakingly drawn flora.

The show, organized with assistance from the Botany Libraries in the Harvard University Herbaria, is just one example of how librarians within Harvard’s vast library system work together to highlight the depth of their collective holdings, according to curator of the Harry Elkins Widener Collection and librarian for scholarly and public programs Peter X. Accardo. Houghton curators also collaborated recently with the Yenching Library on an exhibit of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean objects.

The current show features ten volumes of illustrations, originating in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. Accardo said the inspiration came in part from gardeners and part-time illustrators on the library’s staff, as well as the showing’s timing during the spring and summer seasons. Exhibitions like these, which feature a range of media, are also useful for familiarizing the staff with their diverse holdings—with books and objects numbering in the hundreds of thousands—enabling them to better help researchers and others coming into the library.

“What’s incumbent on many of us… is knowing our collections well—mostly for the benefit of the people that come to consult them,” Accardo said, adding that special collections librarians function best as generalists. “Because our collections are so broad, you always strive to be as useful and as knowledgeable as possible.”

While the objects all feature striking portrayals of precisely drawn plants, the various time periods, origins, and social contexts in which they were created mean that they represent widely different styles.

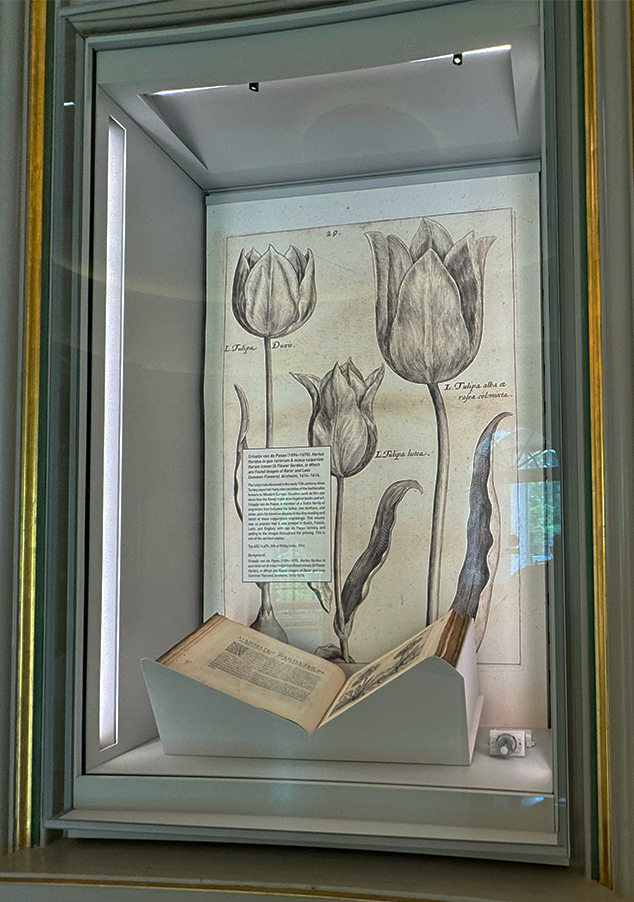

One seventeenth-century book dedicated to tulip illustrations by a Dutch engraver served a partly commercial purpose, according to doctoral student Vanessa Braganza, an exhibitions assistant at Houghton.

“In the seventeenth century in Europe, there was a real tulip craze,” she said, “so much so that people were buying varieties of tulips, prospectively, that hadn’t actually yet been created.” That particular book, while in some sense decorative like others on display, was also a form of marketing. Braganza, in an interview, pointed out other functions for the range of volumes on display.

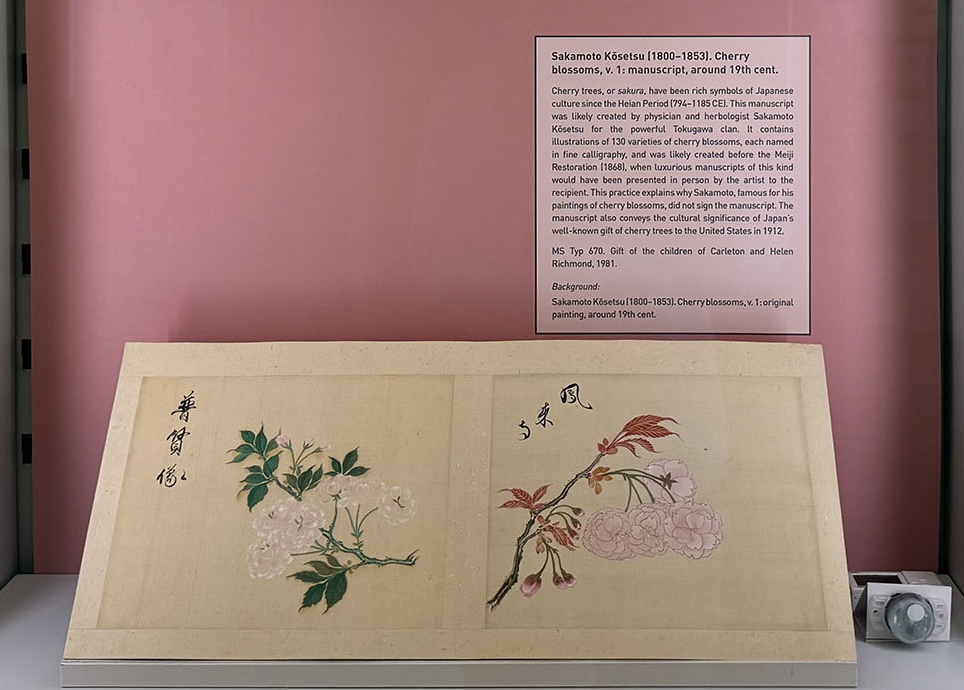

The curators found, for instance, that a manuscript of cherry blossoms from nineteenth-century Japan was crafted by an herbalist for a powerful clan. The cultural significance of the subject—cherry blossoms—and the elegant illustrations and calligraphy depicting them show the work to be a marker of status for the recipient family. In both its materials (each illustration was executed on silk) and its artistry, this book signaled that it was an item for collection—“not unlike a nice house today,” Braganza said—by wealthy and important figures.

A reference book of woodcut plant illustrations used widely across Renaissance Europe coincides with the era of colonization and exploration, when many explorers attempted to describe new environments and cultures in travel literature. Such works bring together a range of flora, many of them unfamiliar to readers, as both an informational and entertaining catalog. In the same way that the knowledge of new worlds brought back to Europe was deeply flawed, Braganza noted, some of the botanical illustrations within the reference book are outright inaccurate.

The Houghton lobby, after a 2022 renovation of the building, admits far more natural light. Although this provides a more modern and welcoming feel, it also means that objects on display must be placed strategically so that the sunlight doesn’t mar them. Among the botanical illustrations, many were positioned to minimize sunlight because of their creators’ reliance on natural pigments to convey the precise color of the plants.

Houghton administrative coordinator Le Huong Huynh, the part-time botanical illustrator whose work served as the spark for the exhibit, said such works have a special power to help visitors appreciate intricate but overlooked natural elements of their daily lives. After seeing the exhibit, “People tend to appreciate what they see… on their walks or their commute home,” she said. “It just brings people back to ‘Okay, I remember…this tree…,’ or ‘I remember this in my backyard that my parents used to grow.’”