When Hamas terrorists attacked Israel last October 7, they unleashed death and destruction—and also inflamed American prejudice on ethnic and religious grounds. Within hours, allegations of such bias came to Harvard. A hasty October 7 student letter holding “the Israeli regime entirely responsible for all unfolding violence” prompted immediate attacks on the presumed authors, and fierce denunciations of their alleged antisemitism, from within the University community and beyond. Much more was to come. In the two months following October 7, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) reported a 337 percent increase in antisemitic incidents nationwide. The campus tensions were further heightened following the December 5 hearing where members of Congress berated then-President Claudine Gay (alongside her MIT and University of Pennsylvania counterparts) for leading campuses the representatives deemed antisemitic.

As the University’s task forces on combating antisemitism and combating anti-Muslim and anti-Arab bias press their work forward and prepare broad recommendations, two reports published on May 16 lay out political and alumni critiques of the Harvard campus climate. They present external and internal perspectives on antisemitism in the community, and argue that beyond individual incidents, the institution (its leadership, its administrative processes, and its curriculum) are themselves antisemitic. Published two days after the 20-day pro-Palestine encampment in the Old Yard ended, these reports represent some of the most pointed criticisms of the University arising from the events since October 7.

The first report, “The Antisemitism Advisory Group and Harvard’s Response: Clarity and Inaction,” was issued by the House Committee on Education and the Workforce. That committee, which hosted the December 5 presidential questioning, has been investigating Harvard’s “response to antisemitic events on its campus.” Its report, an update in its investigation, primarily relies on the testimony of former antisemitism advisory group member Dara Horn ’99, Ph.D. ’06, who relayed student stories and discussed Harvard’s perceived neglect of that first antisemitism group, hastily convened by Gay last October (and since succeeded by the antisemitism task force created by interim president Alan M. Garber in January).

The second report, “The Soil Beneath the Encampments: How Israel and Jews Became the Focus of Hate at Harvard,” was written by the Harvard Jewish Alumni Alliance (HJAA), a group formed last October aimed at “ensuring the safety of Jewish students on campus and…championing a pluralist university culture.” Its report seeks to “explore if and how Harvard as an institution—its faculty and educational programs—might be fueling the hatred we were witnessing.” HJAA’s education vice president Jessica Levin ’87 said that the release of its report was not coordinated with the House committee’s.

“Surviving Harvard as a Jew”

According to both reports, antisemitic harassment and discrimination against Jewish and Israeli students began long before October 7. Among the incidents cited in the HJAA report, for example: In May 2022, a swastika was found carved into a Currier House corkboard. In March 2023, a professor kicked Kim Nahari ’26 out of a class she was visiting after she said she was Israeli. One student told the HJAA that his friend’s teaching fellow for a Holocaust class said that the Holocaust “really wasn’t that bad” and pointed to “all the ways that Jews contributed to the Holocaust happening.” HJAA secretary Zoe Bernstein ’02 said that all of these incidents were reported to administrators, but students “never felt like there was adequate accountability for what they experienced,” because they were not told whether students were disciplined (perhaps in keeping with Harvard’s routine silence on such matters).

Following the Hamas attack and the ensuing war in Gaza, animosities escalated. A student told the HJAA that, on campus, her fiancé was spit on while wearing a kippah (or yarmulke, a traditional Jewish head covering). Observant Jews, multiple students noted, have started wearing baseball caps instead of kippot. During the Harvard Yard encampment (April 24-May 14), several students told the HJAA that they felt offended or unsafe. Some Jewish undergraduates said they were afraid to leave their rooms, walk through the Yard, or study in the libraries. Students told Jewish chaplain Rabbi Getzel Davis that they were going home or moving off-campus “because they couldn’t deal with what was being normalized,” he said in an interview with this magazine.

The HJAA’s report highlights several posts from Sidechat, an anonymous social media platform available only to people with a Harvard email. One justified the October 7 attack, calling Hamas “representatives of Palestinian frustration” and the incursion “a moment of decolonization.” Another called Zionists “killers and rapists of children.” Some used antisemitic tropes, including one poster who ridiculed a student for looking “just as dumb as her nose is crooked.” In January, administrators asked Sidechat to better moderate its content, and the app restricted the Harvard section to undergraduates (rather than anyone with a Harvard email).

In sum, one student told the HJAA, “The only hope of surviving Harvard as a Jew was to not dress ‘too Jewish,’ request the University accommodate Jewish holidays, speak Hebrew, or God forbid, actually support Israel’s right to exist.”

The HJAA interviewed about 50 students as well as some faculty members and recent alumni for its report. Most interviews occurred between November and February, with some additional conversations during the April-May encampment. Although two students are identified by name, the rest appear in the report anonymously. The HJAA report concludes that it was “informative” that these students’ feelings were “so similar.” (Reporting to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences on May 7, cochairs of the two University anti-bias task forces described hearing strikingly similar accounts of biased, discriminatory, or shunning behavior based on apparent ethnic or religious identity for members of the community who are Jewish, Muslim, Palestinian, or Arab.)

HJAA’s Bernstein conducted about half of the interviews, starting with one student whose mother she met and then finding more students through “word of mouth,” she said. She said that people have asked whether the cohort of students HJAA interviewed was sufficiently broad or representative to give an accurate picture of conditions on campus. She responded, “If this was any other historically discriminated against minority, those kinds of questions would not be asked.” If approximately 50 students from “another group came forward with stories like we were told,” she continued, “we can’t imagine someone saying, ‘But does every person in that group feel that way?’”

“The Narrative…Taught at Harvard”

Turning from personal conduct and experiences, the HJAA report criticized Harvard’s academic treatment of Israel-Palestine issues, asserting that its instruction is based on antisemitic propaganda. The narrative that Israel is a settler-colonialist state conducting a genocide, according to the report, was “the brainchild of the Soviet Union during the Cold War.” The USSR “recognized that overt antisemitism wouldn’t fly so soon after the Holocaust,” the HJAA argues, so masked it as anti-Zionism. This biased approach, the report maintains, tainted much campus teaching and many guest speakers’ presentations, which then shaped student rhetoric at protests and toward peers.

HJAA members combed through Harvard’s public-facing course catalog and event listings, showcasing “events that spread the virulently anti-Israel narrative.” Phrases that the HJAA picked out included “apartheid,” “genocide,” “military occupation,” “Nakba,” “settler-colonialism,” and “structural racism.”

The authors of the HJAA report cite anti-Israel ideas taught by Harvard professors and shared at Harvard events as the source for the rhetoric they perceived as antisemitic during campus protests (described in the report as “anti-Israeli, pro-Hamas”). “The narrative…that was taught at Harvard before October 7,” said HJAA social media and media relations vice president Roni Brunn ’96, “is being seen in the protests, and that connection was not made anywhere.” The HJAA says that the narrative diffusion does not take place just in the classroom, noting that there was a faculty tent at the encampment.

The report did not attempt to specify when anti-Israel and anti-Zionist speech turns antisemitic (although it does advocate adoption of a widely discussed and highly contested definition of antisemitism that would be used to evaluate allegations of harassment, discrimination, and intimidation). “We are not interested in debating whether anti-Zionism is antisemitism,” said Levin. “We are looking at the bullying, the exclusion, the harassment facing Jewish students.”

The HJAA also raised concerns that people in positions of educational authority used their status to influence political matters. In an incident described in the report, a student who agreed to have lunch with a proctor said that they “have never heard someone praise terrorists like he did….I just remember the trauma of that conversation.” Another reported that a teaching fellow “canceled class to go protest” with the Palestine Solidarity Committee, a student group that spearheaded pro-Palestine campus protests.

Finally, the HJAA raised questions about donor influence on the University—specifically, funds from sovereign sources the report described as “Middle Eastern anti-democratic governments.” Citing University World News, the HJAA report claimed that Harvard’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies (CMES) allegedly received $1.5 billion from foreign entities between 2020 and 2023, and that Middle Eastern authoritarian nations gave the University $894 million between 2014 and 2019. (According to Harvard’s consolidated, audited financial statements, in the fiscal years 2020-2023, for the entire University, current use giving averaged about $500 million annually and total giving—for current use, endowment, non-federal sponsored research, and other categories—averaged about $1.3 billion annually.) “Once you research event after event on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from one perspective, using the same language, with speakers with a horrific paper trail of antisemitism,” said Levin, “you start to understand directly what that money is buying them.”

Update, July 11, 2024: A University spokesperson refuted the University World News report, stating, “CMES, which has a $1.8 million annual budget, has not received anywhere near $1.5 billion in funding from all sources combined, foreign and domestic, since its inception in 1954. Also of note, for the period 2020-2023, CMES did not receive any funding from foreign governments or allied entities, Middle Eastern or otherwise.”

“The Bureaucratic Black Hole”

Much of the congressional report analyzed the antisemitism advisory group (AAG) formed by Gay in late October 2023. Horn and four other committee members threatened to resign on November 5, less than two weeks after the group’s first meeting, “due to frustration with the inadequacy of Harvard’s leaders’ response to increasing antisemitic harassment and a lack of clarity regarding the Group’s charge and future work,” according to the report.

The five committee members who threatened resignation advanced a series of short-, medium-, and long-term measures to improve the University’s response to antisemitism. Some were quickly met by Gay, including announcing that the confrontation between a proctor and a counterprotester was being investigated by the FBI and Harvard University Police Department, condemning the phrase “from the river to the sea,” and establishing an email inbox for the AAG. But Horn told the congressional investigators that AAG members remained confused about their mission, noting that they had no “written charter or charge delineating what our responsibilities would be.”

One particular moment of frustration for the AAG was Gay’s December 5 testimony. Horn said she was “disappointed not to be consulted” by Gay before the hearing and that Gay did not describe antisemitism as “a problem that was pervasive…on Harvard’s campus.”

The House committee expressed confusion about the January 19 formation of the presidential task force on combating antisemitism, which it says “came without a clear explanation of either what had happened to the AAG or why a new and separate task force was necessary.”

Beyond their qualms about the task force’s creation and mission, both the HJAA and the congressional reports critiqued its co-chair, Frost professor of Jewish history Derek Penslar. Horn was frustrated that Harvard appointed “someone who had publicly stated that antisemitism on campus was an exaggerated problem.” HJAA secretary Bernstein expressed disinterest in working with Penslar for the same reason, and because she said he believes “that anti-Zionism is not antisemitism.”

In an interview, Penslar described those characterizations as inaccurate. Those descriptions, he said, emerged from a January 19 post on X by journalist Ira Stoll ’94 that “became its own narrative, and no one asked me, no one read my own work.” Penslar said that Horn’s comment, accusing him of saying antisemitism was exaggerated, is a misunderstanding. He was responding “to a specific discussion…that Jewish students at Harvard were…in danger for their lives.” “Things have been very bad for our Jewish students,” he continued, “but they have not been in that kind of imminent physical danger.” Responding to Bernstein, he denied saying that anti-Zionism is not antisemitism, clarifying “anti-Zionism and antisemitism overlap, but they are distinct,” and continuing, “Of course, anti-Zionism can be antisemitic.” But “it is possible for anti-Zionism not to be antisemitic.”

The HJAA also criticized the administration for not taking its complaints seriously. On January 22, according to Bernstein and the report, members met with a group of administrators (including interim president Garber, appointed January 2; Harvard College dean Rakesh Khurana; and executive vice president Meredith Weenick) and shared a draft version of the document. It was a productive conversation, said Bernstein, though she “didn’t think I had met with the leaders of tomorrow,” saying, “They did not stand proud and tall, they did not have booming voices, you can see that they struggle with taking a position, and I felt like they have their many masters.”

In February, according to the report, Garber asked for a copy to share with the presidential task force. But in April, not having received it from Garber, Penslar asked the HJAA for a copy. “The work that we had done existed in the bureaucratic black hole that we now know to be Harvard’s administration,” said Bernstein.

A “Common Antisemitic Trope”

During the pro-Palestine encampment in Harvard Yard, HJAA’s concerns about antisemitism intensified. Chief complaints in the report included calls to “globalize the intifada” (which some critics say entails the worldwide murder of Jews) and violations of time, place, and manner protest restrictions that made some Jewish students, the HJAA wrote, “feel physically unsafe.”

After the encampment peacefully ended on May 14, Harvard faced further allegations of antisemitism. During her Commencement address, Nobel Peace Prize-winning journalist Maria A. Ressa, LL.D. ’24, used language that some listeners perceived as antisemitic. “Because I accepted your invitation to be here today,” she said, “I was attacked online and called antisemitic by power and money because they want power and money.”

HJAA’s Brunn wrote on X that the line referenced a “common antisemitic trope…that Jews are only after power and money.” The vagueness of that line, she wrote, implied “that antisemitism is a fake complaint made in the quest for power and money.” Toward the end of Commencement, Chabad Rabbi Hirschy Zarchi approached Ressa and briefly asked her to clarify that line before he prematurely left the stage. In a later statement to Harvard Magazine, Zarchi said, “Her classic antisemitic rhetoric was all the more revealing when she went on to slander Israel by falsely accusing it of genocide, and at the same time, say nothing about the greatest massacre against the Jewish people since the Holocaust.” Zarchi also rebuked Ressa for praising the student Commencement speakers, two of whom went off-script to condemn Harvard’s disciplinary decision to prevent 13 pro-Palestine protesters from graduating, and the students who walked out of graduation to protest that and Israel’s war in Gaza. “She called them ‘peaceful protesters,’” he continued. “They were anything but peaceful. They were hateful and violent.”

Three days after the speech, Ressa posted that her words had “been misinterpreted or taken out of context,” saying that line referenced “how Big Tech and people in power seek to divide us, often for their own gain” and “the antecedent is several sentences ahead.”

Requests and Responses

As the House committee continues to investigate Harvard and other universities for antisemitism (and has proposed legislation), the HJAA report outlined six measures that the University administration should “promptly” enact. Their scope suggests that the HJAA authors conceive of antisemitism as a sweeping institutional problem—encompassing University policies, procedures, enforcement, pedagogy, and more—rather than a matter of individual behaviors.

- Swiftly and publicly “enforce the University’s codes of conduct uniformly and without exception, and discipline students, faculty, and staff who violate them.”

- Adopt the “globally accepted International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism, including its examples” into Harvard’s policies for identifying and investigating antisemitic discrimination, harassment, and intimidation.

- Enact clear principles on academic freedom and institutional neutrality.

- Initiate an “independent, third-party investigation tasked with creating a public report of various practices at each Harvard school, including curriculum, events, admissions policies, and student, faculty, or administrative behavior” that might violate the IHRA definition or University policy on anti-discrimination and anti-bullying.

- Investigate the Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging offices at each Harvard school “in light of their failure to sufficiently include Jews and antisemitism in their mission and programming.”

- Train people who address discrimination issues on “the IHRA definition with all its examples” and “the use of social media…to spread hate and bigotry.”

Some of these requests have already been addressed by Harvard. In a May 10 letter to the congressional committee, “Harvard Actions to Combat Antisemitism,” the administration provided updates about its efforts to counter antisemitism, including:

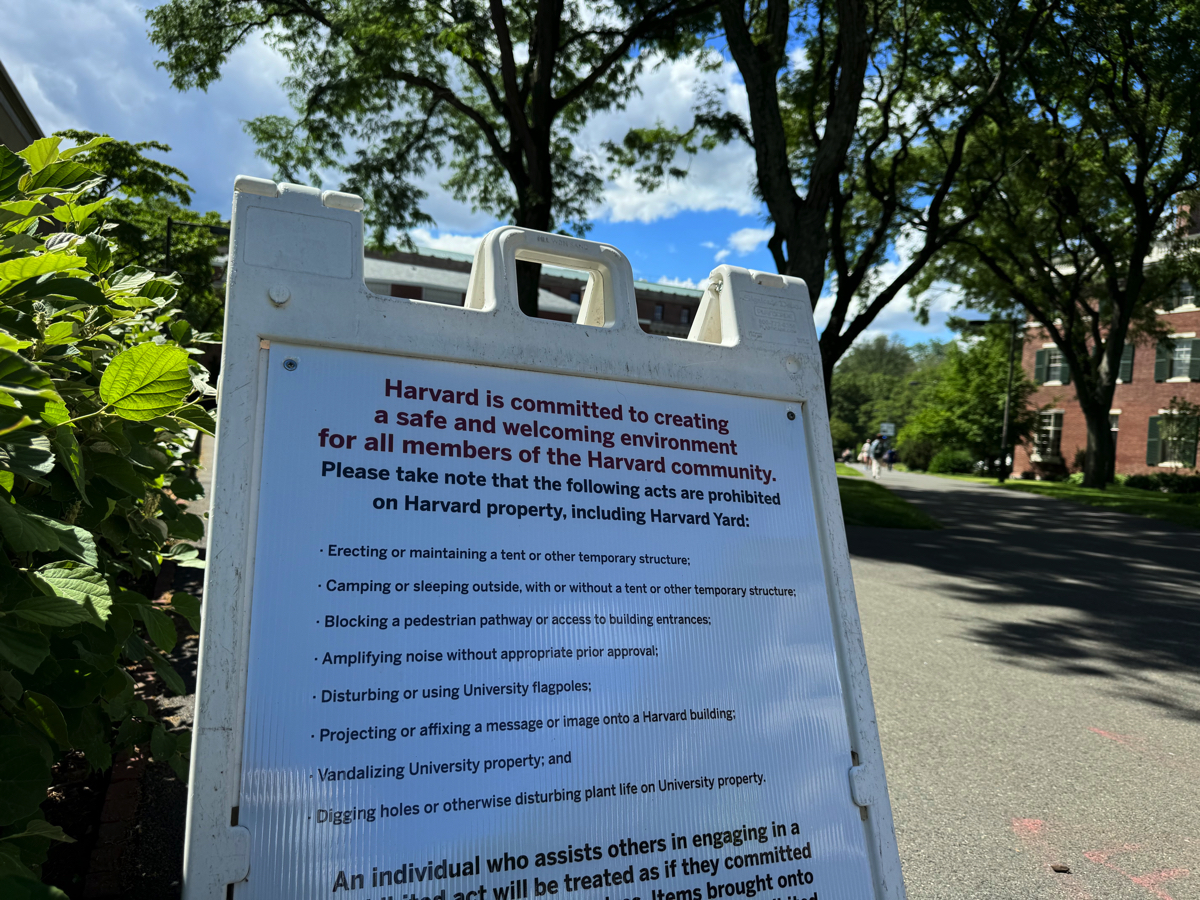

- A January clarification to the University-wide Statement on Rights and Responsibilities, which articulated that certain types of protests (unauthorized occupations) and locations (classrooms, libraries, dormitories, dining halls, and offices) were forbidden.

- Harvard’s schools have “continued to clarify and raise awareness” about University policies that “ensure students, faculty, and staff can continue their learning, research, and work free from harassment and discrimination.”

- A resource titled “Protecting Against Online Harassment” was developed and posted to help community members “recognize, report, and take protective and curative steps against online harassment.”

- Reports of antisemitism, the administration emphasized, “are taken seriously, and are reviewed and addressed in accordance with School and University policies and practices that are intended to combat bias and hate.”

- More than 200 faculty and administrators who participate in disciplinary processes attended an educational session on antisemitism, which Harvard says “will be expanded to other members of the community.”

- Harvard “has further clarified that its inclusion and belonging efforts must reach all members of our community,” with its leaders meeting with the Foundation to Combat Antisemitism and attending dinners at Hillel and Chabad.

Later in May, the University announced that it would no longer issue official statements about public matters that do not directly affect the institution’s core functions of research, teaching, and learning. In mid-June, the antisemitism task force shared their preliminary recommendations with Garber, and co-chair Penslar said the group is preparing its full report for the fall.

But some of the HJAA’s requests are more difficult to enact. Though the report calls the IHRA definition “globally accepted,” much debate surrounds its adoption. Penslar has written that IHRA’s suggested use as institutional policy is “bizarre,” since it was “developed for the purpose of data collection, not policy making.” He also expressed concern about how the definition treats critiques of Israel, writing that it “assumes guilt rather than innocence” and implies that “highly critical but factually accurate statements about Israel are antisemitic.” (In other words, critics of the IHRA standard suggest that its application can chill speech, rather than set reasonable conditions for productive discourse.)

Despite his disagreement with HJAA’s chosen antisemitism definition, Penslar still finds the report valuable. “I appreciate that there is much in the report that is accurate in terms of the difficult experiences that many of our Jewish students have been having for the last several months,” he said. “On the other hand, I think that the Jewish community at Harvard is more divided and complex than the report suggests, and that the responses from Harvard…over the last several months have been considerably more robust and helpful than the HJAA report suggests.”

Anticipating opposition to the report’s proposed third-party audit—which is likely to be interpreted by many faculty members as a dangerous intrusion into fundamental academic rights—HJAA’s Levin asserted that such an inquiry would not jeopardize academic freedom. “We believe that the rights of Jews and other minorities—and ultimately the flourishing of any liberal institution—depends on academic freedom. There is not academic freedom at Harvard right now,” she said. “They are selling it to the highest bidder. They are silencing people such that students say they will never express their views in class. Faculty are telling us it’s indoctrination, not education.”

“Trying to Remodel Friendship and Compassion”

As the academic year came to a close, all sides of the campus Israel-Palestine debate grew frustrated and vocalized increasingly disparate demands. Pro-Palestine student protesters advocated for Harvard to divest from all investments “in Israel, the ongoing genocide in Gaza, and the occupation of Palestine.” The Faculty of Arts and Sciences voted to allow 13 students found by the College’s Administrative Board to have violated University policies during the encampment to graduate (a vote the Corporation declined to accept). And the HJAA called for a full-scale investigation of Harvard’s curriculum and policies to see whether the University promotes antisemitism.

Once students went their separate ways in late May, community members started thinking of the fall, hoping to help reduce tensions. As the anti-bias task forces prepared to address policies and procedures, other campus stakeholders focused on the face-to-face interactions that must ultimately enhance the campus culture and overcome fear, prejudice, and thoughtlessness.

“The University has never before, to my knowledge, dealt with two marginalized groups that are in conflict with each other,” said Rabbi Davis, the Jewish chaplain. Some healing must come in the form of reimagined policies, which, he said, were created for students “protesting against the University, not harassing their suitemates.” But some of what needs to be repaired must come from the students themselves. In late May, reviewing the difficult speech questions many campuses must consider in the wake of the encampments, Emily Bazelon and Charles Homans closed their New York Times Magazine report with this reflection:

At some schools, pro-Palestinian protesters modulated their own speech in deference to the requests of other students, even avoiding the common chant, “From the river to the sea,” which others have defended as peaceful. The protesters who made these choices didn’t do so because of a law or rule. They were sensitive to the nudge of peer relationships and social norms.

Bringing students together to hash out community standards about language is “the only way I can think of for there to be a set of norms about what speech goes too far that students on all sides would accept as legitimate,” David Pozen, the Columbia law professor, said…

At Harvard this spring, amid the protests and headlines, such green shoots also began, tentatively, to appear. Rabbi Davis collaborated with Muslim chaplain Imam Khalil Abdur-Rashid (the two religious leaders shared duties as chaplains of the day at Commencement) and other campus chaplains to run programs “trying to remodel friendship and compassion,” Davis said. In the fall, he wants to continue to encourage students “to build bridges, to repair broken friendships, and to recognize that no matter what your politics are, you should be kind to your neighbors and friends and roommates.” Continuing, he said, “I wish that were the story.”