Ten days before Commencement, early on the cool, fresh morning of Monday, May 13, the lilacs and azaleas at Dana Palmer House were in full, glorious bloom: a lovely scent and sight for the two security guards posted at the Lamont Library gate into Harvard Yard, scanning the IDs of the few passers-by. Within, the Yard was as quiet in its spring glory as it had been during the depths of COVID-19 remote operations: first-year students had moved out, exams were done, Lamont was operating on reduced after-term hours. All that caught the eye was a small presence—a couple of tents, seemingly vacant, pitched at the eastern side of University Hall; and a couple of elevated platforms snuggled up to Tercentenary Theatre trees to support the broadcasting of 373rd Commencement—which at that moment would or would not be held as scheduled there on May 23. The poles for the Commencement platform tent alongside Memorial Church, usually fully erected by this time, had not yet been trucked in.

If Commencement 2023 was celebratory—the end of Lawrence S. Bacow’s presidency, the ebbing of pandemic constraints, the promise of Claudine Gay’s next-generation leadership—this year’s dominating sentiment was relief. The Harvard community had been sundered, and perhaps ultimately exhausted, by a dismal year. Although Commencement took place (it was a near thing; see below), echoes of the challenges facing this institution sounded throughout the week. The normally cerebral Phi Beta Kappa Literary Exercises took on a new tone as Drew Gilpin Faust, president emerita, delivered a powerful oration about the severe threats to higher education. Interim president Alan M. Garber’s baccalaureate acknowledged a year of pain and deep division. But beneath those formalities, the uncertainties and fallout from this year’s protests and disruptions extended up to—and into—the morning exercises: the threatening weather held off, but there was plenty of thunder from the stage (see below and this related story on students walking out of the morning exercises).

A Dismal Year

Just eight days after Gay’s formal installation, the era of good feelings was shattered by the furious campus divisions over the terrorism and war in the Middle East: the October 7 Hamas attack; the national outrage directed at some Harvard student groups’ initial, unreserved support for Hamas; the University’s reactions to those events; and the evolving perspectives on Israel’s overwhelming military response in Gaza. In retrospect, the next weeks unspooled quickly, through Gay’s congressional testimony December 5, the Corporation’s seemingly solid support for her presidency December 12, ultimately followed by its erosion and her abrupt resignation on January 2.

Under Garber, seasoned as provost, and interim provost John F. Manning, who had been Law School dean, the campus calmed somewhat. Garber issued a forceful clarification of rules governing protests and the conditions for free speech, and established task forces on combating antisemitism and anti-Muslim and anti-Arab bias. Manning organized University working groups charged with examining civil discourse and institutional neutrality. All four groups launched listening and information-gathering efforts, with some recommendations for action expected by the end of this month and others in time for the beginning of next academic year and thereafter (read about their reports at the May 7 Faculty of Arts and Sciences meeting). And yet…

Following testimony before a U.S. House committee by Columbia’s president on April 17 and her decision to have New York police remove pro-Palestinian protestors from campus the next day, encampments were established at colleges and universities across the country—including in Harvard Yard as of April 24.

Toward Détente, and Its Rocky Aftermath

Harvard leaders were a bit luckier than their peers elsewhere: the Yard is prime real estate at the heart of Commencement exercises but can be isolated more readily than other institutions’ campus centers by locking the surrounding gates and controlling access—limiting the size of the protest, media coverage, and participation by outsiders. In the ensuing contest of wills, there was also, apparently, a better underlying sense of what could happen, and commitment to avoid major mistakes, than elsewhere. The 60 or student protestors pressed demands (for divestment of endowment assets related to Israel’s military operations in Gaza, for example), occasionally organized vocal demonstrations, and mostly hunkered down. Declining to negotiate, Garber on May 6 notified those encamped, who were violating the University’s time, place, and manner rules for protests, that they would be subject to involuntarily separation from the community: denied permission to take exams, live in Harvard housing, or be present on campus—making them, in effect, trespassers with the consequences that might entail.

Amid dueling faculty and alumni demands—to stave off police action, or to end the encampment post haste—Garber, Harvard College Dean Rakesh Khurana, and others met student protestors on May 8, but reached no agreements. Two days later, notice of the separations was served—but clearly, protestors weren’t going to be physically evicted while parents arrived to move their first-year students out of Yard dorms (separated from contact by plastic traffic barriers). As matters seemed headed for a possible confrontation (MIT and Emerson had police remove protestors, and Harvard’s encampment remained the last one in Greater Boston), additional conversations May 13 yielded agreement to talk further—and the protestors folded their tents the next morning.

Garber moved to end the involuntary separations, while simultaneously urging schools to expedite their individual disciplinary processes; the subsequent suspensions and probations provoked sharp opposition from affected students, some of their peers, and some faculty members—including, as the Crimson reported, a weekend protest march on the interim president’s home. After the Faculty of Arts and Sciences voted on May 20 to include 13 students found not to be in “good standing” by the College’s Administrative Board on the list of those eligible to receive degrees on Commencement, the Corporation, which has the ultimate authority over degree conferrals, ruled May 22 that because they were found not to be in good standing, the students could not graduate today.

And so, formally, the outcome of the protests and disciplinary proceedings pre-Commencement came down to Harvardian procedural rectitude. The affected students may pursue appeals, and will—but plenty of ill will exists on all sides. Background information accompanying the May 22 statement from the President and Fellows pointedly noted that the May 20 meeting at which faculty voted to forward the students’ names for eligibility to graduate had been attended by 115 of 888 eligible members (which is enough for a quorum under faculty rules). Some faculty members already distrust the Corporation and Harvard governance enough to advocate for a University faculty senate; the Crimson reported predictions of a “faculty rebellion” if the Corporation proceeded as it ultimately did in denying the 13 students the chance to graduate today.

All of this was top of mind Commencement morning: far removed from the war itself, the condition of the Israelis still held hostage, and the threat of starvation closing in on the people of Gaza—or the discourse, at the end of most academic years, about teaching, learning, and research proceeding throughout Harvard.

Commencement Overdrive

By May 13, University planners had, literally, explored all graduation options: a remote Commencement; no ceremony at all; or one restructured or relocated—perhaps to the Stadium. Amid all the chaos on campuses nationwide, there was still room for a bit of humor. Sage Stossel ’93 riffed on the contested meanings of college campuses and their sometimes serendipitous uses, from neutral grounds for sharing knowledge to protest venues to (in her case) the site of a touch football game where she met her future husband. And there was sharper commentary, too: The Onion’s mock news report, “Columbia University Gives Students Option to Finish Classes from Prison,” and Barry Blitt’s wicked “Class of 2024” cover for the May 20 New Yorker, depicting graduates in caps and gowns, with their hands zip-tied behind them, each being escorted to receive their diplomas by a police officer.

A peaceful resolution having been achieved here, Harvard at least avoided the indignity of being the target of that kind of barb—and Commencement 373 was on, in overdrive.

Usually, it takes all month to stage the proceedings; now, tradition-bound Harvard’s greatest tradition would be served in just more than a week. Note to the University expense-payables department: any requests for reimbursement from Commencement director Stephan Magro and colleagues for coffee or Red Bull dated May 13 or after are to be approved without further review.

By the morning of May 15, landscapers were on hand restoring and prettifying the turf between Massachusetts and University Halls, where the protestors had tented. Three gigantic Veritas shield banners hung from Widener’s columns. On May 17, fresh sod was unrolled, and the tent over the dignitaries’ platform had been fully erected.

Other, unusual preparations were no doubt underway as well. The Yard gates remained locked, with access restricted to ID holders. That was a prudent precaution after the protests and encampment just past—and a suggestion that Commencement would take place amid heightened security, even without a head of state slated to be the principal speaker.

Dual reminders of the year’s underlying passions and unresolved tensions arrived on May 16, when the U.S. House committee issued an “investigative update” on events of last fall, titled “The Antisemitism Advisory Group and Harvard’s Response: Clarity and Inaction,” and the recently organized Harvard Jewish Alumni Alliance unloaded with its own report, “The Soil Beneath the Encampments: How Israel and Jews Became the Focus of Hate at Harvard.” (And even as the morning Commencement exercises began, yet another congressional hearing aimed at universities’ responses to the Middle East war opened, with the Northwestern, Rutgers, and UCLA leaders being questioned this time.) Amid continuing U.S. Department of Education and congressional investigations, a civil lawsuit, and Harvard’s own inquiries into campus behavior toward and conditions for Jewish, Palestinian, Muslim, and other students, there was plenty of hard work ahead for all community members—and much evidence that the scope for constructive conversation remained narrow, at best.

With that, the stage was largely set. By midday Monday, May 20, with just a few thousand critical items yet to check off the Commencement organizers’ lists (and no doubt after prodigious overtime bills for the weekend), all was in readiness: Tercentenary Theatre was filled with row upon row of uncomfortable chairs, young graduates-to-be were primping and posing for the perfect photo on Widener’s steps, technicians were wiring the last of the video screens, and the Harvard Square CVS was afloat in tacky “Congrats, Grad!” Mylar balloons. Commencement marshals were advised, unsurprisingly, that there would be more substantial police presence than usual this year, outside the gates and within. Journalists were advised that their ability to move about during the morning exercises would be restricted.

As a sign of how improvised and rushed things were, the Harvard Alumni Association did not announce the speaker for the May 31 Alumni Day (actor Courtney B. Vance ’82) until the afternoon of May 20 and the just-in-time seniors, whom the Crimson reported had been unable to secure any its preferred class day guest speakers, let it be known in a group chat that afternoon that dean of admissions and financial aid William R. Fitzsimmons and Currier House Securitas employee Bill Oliverio would step in just two days later! (The community will await another announcement from Fitzsimmons this summer, when the composition of the class of 2028 will be unveiled, the first since the Supreme Court outlawed consideration of race in admissions reviews—yet another issue weighing on the community this year.)

All that remained was the arrival of Commencement weather. After a spring succession of cool, damp, dreary weekends, extending into Monday morning, the sea breezes got shoved offshore and the thermostat dialed up astonishingly, reaching summerlike levels well into the 80s by midweek, with rising humidity and deteriorating air quality to boot—just in time for graduates, faculty members, and dignitaries to wilt within their gowns.

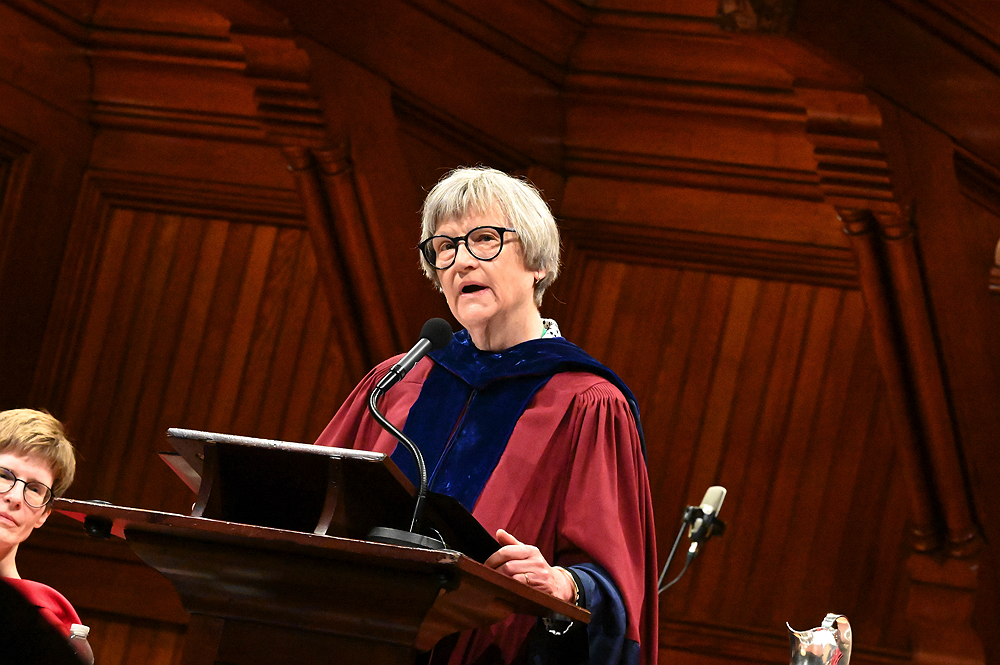

Being “Free and Brave” on Behalf of Higher Education: Phi Beta Kappa

Leaning into the hot climate, Drew Gilpin Faust took full advantage of her role as orator at the Phi Beta Kappa Literary Exercises, on Tuesday morning, May 21, vigorously making the case for higher education and countering the ferocious attacks on universities dominating domestic discourse in recent months. Perhaps as president emerita, no longer constrained by the need to make nice with every possible claimant on the institution, she felt free to express the truths so many current presidents know, but had not articulated, during this battering year.

An historian, Faust began gently, citing Ralph Waldo Emerson’s celebrated 1837 oration, “The American Scholar,” highlighting his injunction that a scholar must be “free and brave”—and afforded protections within the university to proceed in new directions rather than being constrained to be the “parrot of other men’s thinking.” She detailed how criticisms of universities—a subject of her installation address in 2007—have accelerated and intensified, fueled by the “polarizations of race, religion, and politics that grip our country,” posing disastrous consequences for the well-being of individuals who disdain higher education, and for the progress of societies that depend on discovery and learning.

But Faust, a proponent of making “necessary trouble,” did not stop at the level of abstract analysis. She addressed public disinvestment in higher education, the partisan nature of the 2017 excise tax on private universities’ endowments, and broader political misperceptions. “A B.A. has neither an R or a D attached to it,” Faust reminded her student-scholar audience. Fulfilling their role, she acknowledged, requires universities to “reinforc[e] their support for the ideals of free speech” and “[strengthen] their dedication to the open exploration of ideas”—what she called loyalty to “the rule of truth.” After frank comments on ways in which universities haven’t always realized that ideal, she then detailed insidious and overt threats to teaching and faculty appointments, warning (in a not very veiled reference to the events of the past academic year), “We should not be permitting, and certainly not celebrating, a governor or a legislature or a member of Congress who is designing courses or degree requirements, hiring faculty, or proudly claiming responsibility for firing university presidents.”

She concluded:

American higher education is endangered. Universities have rightly been reminded of the imperative to live up to their own values, to be accountable to the rule of truth that I have described. They need now more than ever to be their best selves. But they also need to defend themselves against attacks that are uninformed, undeserved, or rankly partisan, attacks that are explicitly designed to weaken and marginalize a set of institutions that are foundational to American democracy and to the well-being not just of Americans but of people around the globe. Universities are intended to change people, to enable them, to quote the inscription on the Dexter Gate to Harvard Yard, to “grow in wisdom”; universities are designed to question prevailing ideas and assumptions; they are meant to create discomfort, to grapple with the uncertainties and complexities of what they don’t know as well as the realities and the meaning of what they do. Universities have a purpose that transcends struggles for political power or advantage, that flies in the face of the political opportunism that has fueled so many recent attacks.

We who have been nurtured and shaped by universities, we who proudly embrace our identities as scholars “free and brave,” must acknowledge, to borrow from that early PBK oration, both the “dangers” and the “duties” that lie ahead. We must be champions of the promise and purposes of higher education—of the “rule of truth” that it stands for both inside and outside these gates.

Read complete Phi Beta Kappa coverage here.

“We of Divergent Minds”: The Baccalaureate, Class Days, and More

Faust had joked that after “11 years of silence” at the Literary Exercises, “sitting where President Garber is right now” (the president attends, but does not speak), she was “grateful for this opportunity” to appear as orator. Garber’s first change to exercise his new role arose during the baccalaureate exercises Tuesday afternoon. He rose to the occasion deftly, melding the traditions of the form—reviewing the undergraduates’ class identity, conferring wisdom—with realistic reflections on current conundrums.

Acknowledging the most obvious thing about his role, he began (channeling the Grateful Dead), “What a long strange trip it’s been”—and then got right to the point about the strangest element of all: “You have been undergraduates for 1,349 days. I have been interim president for 140 days.” In a sober, heartfelt summing up, he told the class:

This year, we have witnessed together incomprehensible death and destruction in the Middle East. We have experienced, directly and indirectly, grief and rage, fear and worry, skepticism and mistrust. The conflict has opened wounds throughout our community that will be slow—but not impossible—to heal.

On Thursday, we of divergent minds will process together into this space, a space created not by gains—but by losses. Behind me, Memorial Church, dedicated on Armistice Day in 1932, built by our predecessors to honor those from Harvard who served and died in the first World War. Behind you, Widener Library, opened on Commencement Day in 1915, built by a grieving mother in memory of her beloved son.

I hope we are able to heed the lessons of those who preceded us, those who chose to make from their sorrow something new, something that would last. May the losses of this year—of human life and of human connection—of sympathy and empathy—of care—be for all of you—for all of us—an impetus to advance rather than retreat, shining brightly in shadow, and brighter still through darkness.

If there is a Harvard class that can illuminate a path forward for our world, it is yours. I am honored to have had this moment with you. I wish you contentment, health, and love—and everything else you hope to do with your precious time.

Read detailed baccalaureate coverage here.

A bumper crop of ROTC students received their commissions at the annual ceremony on May 22.

And there was plenty of class day wisdom:

•Addressing a kind of service different from those the ROTC graduates will puruse, former faculty member Nicolas Burns, now U.S. ambassador to the People’s Republic of China, told the Harvard Kennedy School’s class day audience that amid global crises and challenges, their international network could, and must, play an essential role in finding solutions.

•At the Graduate School of Education’s class day, long-time faculty member Howard Gardner, now emeritus, explained how his own pedagogy had evolved, for the better, and summoned the audience to embrace “the heart of teaching.”

•U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland told the Law School crowd about three Harvard Law alumni who have made a difference within her vast part of the federal government.

•And Karenna Gore ’95, talking at the Graduate School of Design, focused on one of those global challenges Burns listed: Earth, she noted, was “well-located, with a good site and orientation”; the climate crisis made clear that “It is not the earth that needs fixing, it is us.”

During the College class of 2024’s hurriedly programmed class day, program marshals Tarina Ahuja ’24 and Shruthi Kumar ’24 read the names of classmates who had been found not in good standing and therefore ineligible to graduate—a fraught moment, not least because Kumar was chosen to be the senior English orator during the morning exercises (see below). Urging classmates to be “unlikely inseparables” (able to be friends despite disagreements), student speaker Jeremy Ornstein ’24 declared, “In 2024, I am proud of us undisciplinables, including the people who speak out against the killing of innocents, even when it is unpopular—no matter who or when or where.”

Separately, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, now named in honor of Kenneth C. Griffin ’89, whose thirty-fifth reunion falls this year, conferred its Centennial Medal on four distinguished alumni (described in further detail here), reflecting the value of advanced study and honoring their contributions to learning and society:

•Martin Duberman, Ph.D. ’57, an historian, biographer, playwright and gay rights activist;

•Myra Marx Ferree, Ph.D. ’76, a sociologist and leading feminist scholar;

•Joan Argetsinger Steitz, Ph.D. ’68, a molecular biologist known for her fundamental work on RNA; and

•Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Ph.D. ’73, an art historian who specializes in Dutch and Flemish paintings.

The Main Event

Commencement remains super-sized, a reminder that the pandemic caused many students to defer enrollment or take leaves when instruction was conducted remotely during the 2020-2021 academic year. As they have returned to their studies, a bulge of graduates continues to qualify for degrees each year. For this 373rd edition, the Harvard Gazette reported, 9,277 degrees were conferred (plus the candidates’ accompanying friends-and-family posses, of course): in line with last year, but still more than the cohorts averaging 7,500 to 8,100 in the years preceding the COVID-19 cataclysm.

In recent Commencements, there has been a tendency to script Instagrammable moments: last year, Katalin Karikó’s teddy bear, Tom Hanks’s volleyball (a reference to his Cast Away). Amid campus controversies and concern about higher education, this time sobriety appropriately prevailed—a business-like spirit manifested in the new players in the leading parts. Garber, who as provost had run the presentation of degree candidates and lauding of the honorands’ accomplishments, now found himself as interim president at the rear of the Commencement platform, doing the more restrained duty of formally conferring the degrees. (He was rewarded for the honor by being seated in the president’s traditional, manifestly uncomfortable chair.) Manning, now provost, had the longer parts to say (perhaps a special burden of his new office, as he has been known as very reserved in manner). And University Marshal Katherine O’Dair, who had picked up additional enormous responsibilities as President Gay’s chief of staff, has shed those obligations and was back in her role as Harvard’s pilot of protocol and Commencement emcee. All was in readiness by 9:50 a.m.

From the get-go, one sensed that this Commencement differed in other ways, too. As ticket-holders queued to get into Tercentenary Theatre, they got both Crimsons and an official-looking “program”: a clever duplicate, inside it honored “over 40,000 Palestinians and 1,200 Israelis killed, 9,500 Palestinian political prisoners, 125 Israeli hostages, people the world over struggling for freedom, and the courageous students at Harvard and beyond who have protested a genocide at personal significant personal and professional risk.” A manifesto for divestment, it was circulated by Harvard Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine. Overhead, a plane towed a banner: Jewish Lives Matter.US.

Following the traditional—and deafening, and ridiculous—call to order by Peter J. Koutoujian, M.P.A. ’03, the sheriff of Middlesex County, soloist Isabella E. Peña ’24 did the honors, singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” She has had plenty of prior practice. A Cabot House resident from Miami, Florida, the joint government-East Asian studies concentrator (who also did a secondary field in theater, dance, and media, while completing a dual degree at Berklee School of Music) sang with a band, the Yard Bops, and with the Harvard Opportunes and performed with Hasty Pudding Theatricals. An American Idol competitor in 2020, she has belted out the anthem at least three times each for the Boston Celtics, Red Sox, and Miami Dolphins, plus assorted times for the Miami Heat, Marlins, Inter Miami, University of Miami teams, and others. After that, 32,000 folks in Tercentenary Theatre must have seemed child’s play.

Peña’s extensive prep showed, in her blow-the-speakers-out rendition of the anthem. After she concludes her planned studies at Harvard Law School, she ought to be able to enliven firm picnics or other events on behalf of some future employer.

• The Chaplains’ Prayers. Suitably for a campus, a nation, and a world riven by war in the Middle East and elsewhere, the duties of chaplains of the day were shared by Imam Khalil Abdur-Rashid, the Muslim chaplain, and Rabbi Getzel Davis, campus rabbi. After a land acknowledgement to the Massachusett people by Imam Khalil, Rabbi Getzel spoke about aloneness and compassion:

We gather here today to celebrate a momentous occasion, a day filled with joy, with pride, and with great accomplishment. Often, when we gather together, we notice, ironically, the ways in which we are alone.

We find ourselves navigating the seas of loneliness and isolation, yearning for connections and understanding. Too often, we seek community in standing together against. Against others, against our neighbors, even against injustice fueled by hate.

Rebbe Nachman of Breslov offers us an alternative. Describing the experience of alienation and separateness, he uses the metaphor of entering a dark room where all we can perceive is darkness. With patience and time, he teaches, our eyes adjust and we find that we can in fact see.…Darkness dilates our eyes—it opens us. Our own vulnerability, fears, and losses attune us to a universal human experience.

I bless us today with another way to engage with our sense of separateness—compassion. Compassion lies not in numbing our alienation or fighting against it. Instead, “compassion,” literally “suffering together,” comes from recognizing that our own experience of alienation resembles the universal experience of others. It is our vulnerability, not our strength that makes us human. In our separateness, we find You—Oh Lord.

So, as you all step out into the world, carry with you the knowledge that on one level, you are alone. The experience of separateness will follow you through life.…Let it transform you. Let it inspire you. Let its universality call you to compassion, to sacred service, and to love.

Imam Khalil also stressed compassion and community despite differences and losses:

Let us Pray—In the Name of our Lord, The Lord of Compassion, the Giver of Merciful Love. We praise You and seek Your help in all matters.

You created us as different people, races, tribes, and nations so that we would come to know one another, and to understand that in Your Divine eyes, the most honored of us are the ones most mindful of You! But we have felt alone, so help us feel together; help us to be together; to heal together; to uplift each other together.

Help us remember that we are indeed brothers and sisters of one another; that we are to cultivate and preserve peaceful bonds with each other; and that we are to be mindful and grateful for all the blessings You have graced us with.…

Kindle inside us [the] spirit and grant us the courage to weather the storms of hate by cultivating new climates of hope.…

Expand our hearts; Gift us fluency in the language of unity; through the dialect of restraint; with the tongue of tolerance; Help us to call others to the path of love and justice using wisdom with courage; conviction with courtesy; gentleness with tenacity.

You have gathered us here, as one community. And despite our differences, our traumas, our loss, and our loneliness, we are indeed together in our need for You and in our hope in You. We ask out of Your loving mercy and grace, that You position us to remember where we came from, who we are, and what role we must play, to do our part, to make this world a better place for us all and for those to come.

The two faith leaders then joined to lead the Commencement crowd in saying a collective “Amen. Shalom Aleichem. As-Salaamu Alaikum. May Peace be with all.”

Following the traditional anthem, Domine, salvum fac, performed by the Commencement Choir and University Band, Garber came forward to offer congratulation and to offer a message that he may have hoped would both convey sympathy and invoke a common cause in pursuing the morning’s exercises. “As our ceremony proceeds,” he noted,

some among us may choose to take the liberty of expressing themselves to draw attention to events unfolding in the wider world. It is their right to do so. But it is their responsibility to do so with our community—and this occasion—in mind.

(In the event, those expressions would take two forms: fiercely critical student oratory from the stage, and a significant movement of people within Tercentenary Theatre: not a rush toward the Commencement platform—which was separated from the crowd by crimson-covered crowd-control fencing—but a walkout by a significant number of students who chose to withdraw from the proceedings in protest.)

Garber continued:

That said, I acknowledge that this moment of joy for us coincides with moments for others that we cannot comprehend—moments of fear and dread, grief and anguish, suffering and pain. Elsewhere, people are experiencing the worst days of their lives. Here and there, we are all human beings, seeking connection and contentment, finding comfort in community and rituals, trying simply—as difficult as it may be—to make sense of things as they are, to make sense of one another and of ourselves.

Sympathy and empathy atrophy without exercise. We will now observe a minute of silence.

Following the silence, observed in common cause, Garber continued:

Every Harvard Class enters a world in need. Yours is no exception. No matter your field or discipline, you will have opportunities to help fulfill those needs and to make things better. May you continue to approach your dealings with diligence and integrity—to treat others with care and compassion—and to support and encourage one another as you have done these many days.

If, along the way, you find yourself disheartened…fortify yourself with the work of the research university. Having spent most of my career at two of the best of them, I can say with confidence…that no other type of institution does more good in the world.

Much of what stirs people’s hearts and gives them hope—for longer and better lives, for stronger and safer communities, for a sustainable future—can be traced back to institutions like this one—and to people like you.

Then it was time for the student speakers’ Big Moments (read about each orator here)—traditional in the form of the Latin orator, but thunderous in the off-script moments that followed.

• Latin Salutatory. Blake Alexander Lopez ’24: “Distantia Propinquior” (“A Nearer Distance”)

During middle school, Blake Lopez, of Crown Point, Indiana, became intrigued by Sweden—the country’s history and architecture—and began immersing himself in the language, igniting a general passion. Alongside English, he now speaks four languages (German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish) and reads another six (Old English, French, Old French, Latin, Ancient Greek, and Swedish)—so a Commencement address in Latin was not much of a stretch. The Kirkland House resident, who completed a joint concentration in classics and linguistics, found language study a gateway to community, leading the undergraduate linguistics society and creating a new language with clubmates. It has two noun classes (akin to many languages’ gendered structure). “We have Harvard nouns, and Yale nouns,” he says. “Every word that we make in our language, we make a value judgment. Is it a good word or a bad word? If it's a good word, it's a Harvard noun. If it's a bad word, it's a Yale noun.” (It is unknown how this might evolve further next year, when Lopez extends his classical language studies while pursuing a master’s degree at Oxford.)

Reflecting on the experience of arriving at the College “with no knowledge of what Harvard life was like before the pandemic,” he recalled establishing friendships via Zoom, where “creative backgrounds displayed our personalities and our faces took the forms of cartoon animals.” Undaunted, Lopez said, the class members had overcome: “In spite of these challenges, it is marvelous to see how strong an identity our class shares. Even if our social skills are slightly undeveloped… we are well equipped, relying each other’s help, to find new, creative, usually legal, and, above all, exciting paths forward.”

Read Lopez’s full text, in Latin and English, here.

• Senior English Address, Shruthi Kumar ’24: “The Power of Not Knowing”

Omaha native Shruthi Kumar ’24 says she often does not know what to think. Growing up, she was often confused by the gendered traditions of her parents’ South Indian villages and her high school friends’ conservative beliefs. But she approached such uncertainties with generous curiosity. “From that place of not knowing,” she says, she was able to connect with “people and learn where they’re coming from, how they’re thinking”—a mindset she attributes, in part, to daily yoga practice and meditation: aids to navigating the “troubles of life.” Her passion for health blossomed at the College, where the history of science and economics double concentrator launched a campaign called “Making Harvard 100% Period Secure.” It has resulted in the installation of menstrual product dispensers in nearly every female and gender-neutral bathroom on campus. She also helped lead the Harvard South Asian Association, sat on the Harvard University Health Services student planning committee, and organized in support of affirmative action. Unsurprisingly, she is headed for a career in healthcare or public health.

Kumar found campus conversation on divisive issues disappointing. Compared to high school, she says. “I never knew intolerance the way that I learned it here.” Accordingly, her Commencement address aims to encourage people to embrace uncertainty and difference. “In the history of science,” she said, “we often look for what is missing. What documents are not in the archives and whose voices are not captured in history? I’ve learned silence is rarely empty, often loud. What we don’t know can sometimes tell the most powerful story.”

The same lesson emerged outside the classroom:

I learned this not only in the classroom, but also from the Class of 2024. In reflecting on our collective journey at Harvard, I’ve learned it’s often the moments of uncertainty from which something greater than we could have ever imagined grows. Our class has experienced more than our fair share of the unknown.…

Which brings me to our senior year, a year on campus that has been marked by enormous uncertainty. In the fall, my name and identity alongside other black and brown students at Harvard was publicly targeted. For many of us, students of color, doxxing left our jobs uncertain, our safety uncertain, our well-being uncertain. This semester, our freedom of speech and our expressions of solidarity became punishable.

Taking a deep breath, she said, “As I stand before you today, I must take a moment to recognize my peers, the 13 undergraduates….” As cheers erupted from the audience, Kumar paused, took several deep breaths, then gathered herself, repeating “the 13… the 13 undergraduates in the class of 2024 who will not graduate today. I am deeply disappointed by the intolerance for freedom of speech and the right to civil disobedience on campus,” she continued, citing student, faculty, and staff petitioners in the students’ support. “What is happening on campus is about liberty,” she continued. “This is about civil rights and upholding democratic principles. The students had spoken. The faculty had spoken. Harvard, do you hear us? Harvard, do you hear us?”

Reverting to her prepared text, Kumar continued:

Now, we are in a moment of intense division and disagreement in our community over the events in Gaza. I see pain, uncertainty, and unrest across campus. It’s now, in a moment like this, that the power of “not knowing” becomes critical.

Maybe we don’t know what it’s like to be ethnically targeted. Maybe we don’t know what it's like to come face to face with violence and death. But we don’t have to know.

Solidarity is not dependent on what we know, because “not knowing” is an ethical stance. It creates space for empathy, solidarity, and a willingness to listen.

I don’t know—so I ask. I listen. I believe an important type of learning takes place, especially in moments of uncertainty, when we lean into conversations without assuming we have all the answers. Can we see humanity in people we don’t know? Can we feel the pain of people with whom we disagree?

By the end of Kumar’s remarks, the morning had been changed. She received a thunderous ovation from much of the student body present.

Read Kumar’s full text here.

• Graduate English Address, Robert L. Clinton IV, J.D. ’24: “On Being Good”

At New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, Robert Clinton created his own major, in the sociology and politics of urban agriculture. After graduating in 2016, he deepened his interest in urban design and change during a two-year Marshall Scholarship at University College London, where he earned a master’s in sustainable urbanism and a second master’s in public administration. Following three years at San Francisco’s office of civic engagement and immigrant affairs, he entered Harvard Law School in 2021. There, he participated in the capital punishment and federal tax clinics. “So much of law school feels theoretical,” he says. “It was really a privilege to work with actual people and try and help them.”

Clinton now returns to New York City to clerk for a district judge in the Southern District of New York. In his Commencement address, he hopes to inspire fellow graduates to use their degrees for good. “At a place like Harvard, where people are chasing after credentials,” he says, people “sometimes forget that having a Harvard degree doesn’t actually mean a whole lot if you’re not going to use it to do something good.”

After a brutal year during which he was “reminded of how exposed we are. Antisemitism. Islamophobia. Anti-Arab bias. Death threats. Doxing. Losing jobs. Losing friends,” and, he improvised, “Losing our right to free speech,” Clinton said, “our choice is to either be upset about our vulnerability, or to use that vulnerability to connect with others. And that choice will manifest in pivotal moments when people look to us for guidance. We will be decision-makers, and we’ll have discretion. Over and over, we will bear responsibility for making decisions that’ll change other people’s lives.” Among them he mentioned:

Women dealing with the consequences of no longer having rights over their own reproductive systems. Immigrants fleeing places where there are no universities left from which to graduate. Climate refugees escaping homes that have become uninhabitable. And people whose only mistake was being born poor in a country that criminalizes poverty.

Acting on their behalf—“being good”—he said, “can mean a lot of things: Standing up to dictators. Being mentors. Using your Harvard network to help people who didn’t go here. Voting. Advocating for a ceasefire in Gaza”—another significant applause line. “If you disagree with some of those, that’s fine,” he continued. “There are lots of ways to be good.” Again he improvised, “It’s not very good to announce the day before Commencement that 13 seniors will not graduate”—a line that prompted cheers of “Let them walk!”

The important thing is to find some way of doing so, Clinton insisted, “Because not being good would be a waste of the privilege of having graduated from this beautiful place, Harvard.”

Read Clinton’s full text here.

The Commencement Choir then sang an anthem, “Gates of Harvard Yard,” composed by Jenny Yao ’22. When the work debuted, during her class’s baccalaureate, she said she wanted to celebrate the physical environment “that enveloped us for the last four years—pandemic aside,” noting that she was particularly inspired by the Bradstreet Gate, named for the first established female poet in the New World. One of Anne Bradstreet’s poems came to represent for Yao a reflection on her and her class’s journey—where they had been and where they were going—as they, too, prepared to explore a new world.

During the past month, of course, those gates have played an unaccustomed role: rather than ushering people into this community of learning, they have been locked tight, isolating the pro-Palestinian encampment and, after it ended, securing the Yard against further protests while Commencement preparations proceeded. In the meantime, Yao herself has continued to explore new worlds, as a student in the Harvard/MIT M.D.-Ph.D. Program in Health Sciences & Technology, where she is studying chemical biology and host-microbe interactions. Her continued devotion to learning was perhaps a suitable introduction to the principal business of the day: graduating the candidates and sending them out to commence their lives’ next stages.

• Conferring of degrees. Thus it was interim provost Manning’s turn to explain the process through which Harvard actually confers degrees: by a presidential act of speech, as authorized by the governing boards, on each cohort of students en masse. (They get diplomas later, one by one, in ceremonies at the undergraduate Houses and their respective schools and other venues.)

Garber and Manning were familiar faces in new roles, but plenty of recently appointed figures were involved in the rites, too. Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean Hopi Hoekstra, Harvard Divinity School Dean Marla Frederick, and Harvard School of Public Health Dean Andrea Baccarelli—all appointed by President Gay—were all at the plate for the first time. John Goldberg, Manning’s interim successor at the Law School, was also new to the role. Harvard Graduate School of Education dean Bridget Terry Long presented her many degree candidates for the last time. (During the search for her successor, Nonie Lesaux will serve in an interim capacity.) The Kennedy School’s Douglas W. Elmendorf was also involved for his last time as dean; his successor, Jeremy Weinstein, has a fair idea of what lies ahead for him on May 29, 2025, having been on the receiving end (he is Ph.D. ’03).

In ordinary years, those transitions were made note of. Not so this time. Anticipating the unusual circumstances, the form of conferral was radically streamlined. Gone were the customary formalities by each dean beginning “Mister President, Fellows of Harvard College, Mister President and Members of the Board of Overseers: As Dean” of whatever school, presenting degree candidates, and the president’s refrain of “By virtue of authority delegated to me….” Instead, each dean identified her or his faculty, presented the candidates, and Garber said, “I confer on you the degrees…” and that was pretty much that.

No sooner had the conferring begun, with the long-studying Ph.D.s, brilliant in their Crimson gowns, the first to be made official alumni, followed by master’s of arts and sciences candidates, than the cheers of “Let them walk!” swelled in volume—and at least several hundred students walked out of Tercentenary Theatre, bound for an alternative “People’s Commencement” ceremony in Epworth Church, honoring the pro-Palestinian protestors who were denied their diplomas in the official proceedings.

Unsurprisingly, given the circumstances, another tradition was abandoned. The College class marshals and summa cum laude candidates were not invited to “draw near” the platform for congratulations from the president and deans—the farthest thing from anyone’s thought today.

Even the music was rearranged. The anthem based on Psalm 78 (St. Martin’s), a tradition dating back to the inception of Harvard Commencements, is typically sung to break up the conferral, but it was skipped. And “Veritas: A Celebration of the Centuries,” created by the multitalented engineering sciences/physics/law student and composer Chung Hon Michael Cheng, A.B.-S.M.’19, J.D ’24, based on texts from Harvard’s five centuries (the seventeenth through the twenty-first), was sung only after Garber (finally invoking “The authority delegated” to him by the governing boards) conferred the undergraduate degrees, rather than as preface to them. Composed and performed in 2019, for the baccalaureate, it ends with an upbeat charge appropriate to most Commencements, “So wake up—/Wake up!/Lift off”—which may have felt different in context this year.

The Honorands

The University then celebrated the accomplishments of a half-dozen honorary-degree recipients (described in detail here), with the interim provost introducing each and Alan Garber reading the citation and conferring their Harvard degrees, in this order:

Gustavo Dudamel, music and artistic director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela, his home country, and music and artistic director-designate of the New York Philharmonic (effective 2026). As befits a champion of young musicians, Dudamel was toasted at the dinner for the degree recipients Wednesday night with an arrangement of “Alma Llanera” (“Soul of the Plains”), a Venezuelan song that celebrates the llanero herder culture and is now considered an unofficial national anthem—performed in this case by a quartet of undergraduates, one of whom reportedly had to take a crash course in the use of gourd maracas. Doctor of Music:

If music be the food of love,

he is passion’s chef supreme;

the dude who delights us with Bernsteinian gusto,

he conjures sonic magic with the wave of his baton.

Jennie Chin Hansen, immediate past chief executive of the American Geriatrics Society, and past president of AARP (a position she held during the development of the Affordable Care Act)—a pioneer in care for the elderly. Doctor of Humane Letters:

Selfless in service to seniors in need,

fervent in striving for systemic change,

a venerated nurse who’s made caring her credo;

her compassion for others never gets old.

Sylvester James Gates Jr.. [Updated May 24, 10:40 a.m. at the request of Professor Gates, who wishes to be identified as]: Clark Leadership Chair in Science, with a joint appointment in the department of physics and the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland, and Distinguished University Professor and a University System of Maryland Regents Professor, a leading theoretical physicist who has worked on supersymmetry, supergravity, and superstring theory—and a fellow in the Harvard Society of Fellows from 1977 to 1980. Doctor of Science:

A first-string physicist whose mathematical forays

help us to fathom the fabric of the universe;

an educator who unlocks the gates to opportunity,

he evinces how imagination can encircle the world.

Joy Harjo, twenty-third Poet Laureate of the United States, 2019-2022, the author of 10 books of poetry (plus several plays, children’s books, and two volumes of memoir), and a performing musician who played for many years with her band, Poetic Justice, and has produced seven albums. Doctor of Literature:

Searching for transcendence as she traces trails of tears,

seeking hope amid struggle, light amid loss,

an inspiriting paragon of poetic justice

who hears in the night sky the birdsongs of dawn.

Lawrence S. Bacow, M.P.P.-J.D. ’76, Ph.D. ’78, who became Harvard University’s president on July 1, 2018, and served through June 2023, guiding Harvard through the COVID-19 pandemic safely while accelerating development in Allston and investing in significant new research programs in quantum science and engineering, climate change and sustainability, and human and artificial intelligence—and supporting deep research into Harvard’s legacy of slavery. Of note, given the citation, Bacow is a lifelong sailor. (The week was a twofer for Bacow, who also received an honorary degree from Wheaton College, where he was a trustee from 1999 to 2009.) Doctor of Laws:

His deft hand nimble on an often slippery tiller,

his clear eye focused on the gleam of new horizons,

his sharp mind buoyed by humility and heart,

he steered the Crimson fleet through a time of change and storm.

Maria A. Ressa, co-winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021 (with Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov) for her brave, independent news coverage of her native Philippines. Doctor of Laws:

Amid times of unrest, facing threats and arrest,

she rivets her focus on facts, truth, and trust;

an intrepid, innovative investigative journalist,

irrepressible in pressing for freedom of the press.

The degrees having been briskly bestowed, Garber welcomed the honorands to “this Society of Scholars,” and gave a just-the-facts two-sentence segue to get Ressa ready to “address this assembly.”

The Commencement Address, by Maria A. Ressa:

Ressa spoke in part from her text (available here as prepared for delivery). Her focus, as throughout her recent career, was on the threats to democracy posed by social media, corporate manipulation of data and information, the disappearance of credible news and information, and the destruction of social truth. As the core of that message, she told the graduates:

[Y]ou’re standing on the rubble of the world that was. Recognize it. I said this in the Nobel lecture: An atom bomb exploded in our information ecosystem. Social media turned our world upside down, spreading lies while amplifying fear and anger, fueling hatred. By design. For profit.

Whether it’s the AI of social media or generative AI, we don’t have integrity of information, of facts. Without facts, you can’t have truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust. Without these three, we have no shared reality, no rule of law, no democracy. We can’t begin to solve existential problems like climate change.

This outrage economy—built on our data, microtargeting us—transformed our world, rewarding the worst of humanity. Online violence is real violence. And people are dying—from genocide in Myanmar, fueled by Facebook according to the UN and Meta itself…to Ukraine, Sudan, Haiti, Armenia, Gaza.

The challenge today is whether our international rules-based order still works. Does it? The challenge is justice, core to our humanity. Too many powerful people are getting away with impunity—from countries to companies, and it is dividing us in ways that are literally destroying us…destroying democracy.

Destroying TRUST.

“The battle to regain trust begins now,” she urged. “With all of you. Harvard boasts it educates the “future leaders” of the world. Well, if you future leaders don’t fight for democracy right now, there will be little left for you to lead.”

Over and Out

Katie O’Dair, the marshal, thanked Ressa for her presence and speech, and then got the “assembly” (as the program calls everyone present) engaged for their part: singing “Fair Harvard.”

Then, at a moment when the University could really use some blessings, the now familiar and reassuring Pusey Minister Matthew I. Potts arose to offer the benediction, on behalf of those who “have come through something trying and…have survived”:

As we conclude, I am grateful to offer the blessing.

In its ancient roots, blessing does not confer goodness, it honors it. It is not a talismanic spell of protection; it is an act of recognition. Blessing is a gesture of praise: not a way of making something good, but a way of acknowledging what is already good.

In its medieval roots, meanwhile, blessing carries a sense of woundedness. To be blessed means to have come through something trying and to have survived. Blessing honors you for who you are, but it also bends its knee before all you have been through.

Harvard class of 2024: you have been through it, through pandemic and isolation and war and war again, through transition and upheaval and strife and alienation and grief. So on behalf of all those crowding this Tercentenary Theatre, on behalf of those who couldn’t travel or couldn’t get tickets and who are celebrating you somewhere else, let me assume the singular privilege and the distinct honor of saying simply: bless you.

Bless you for all you have worked for. Bless you for all you have stood for. Bless you for who you have been. Bless you for who you will become.

Harvard graduates: During these trying times, you have been a blessing to us, and we see it. We see the scope and size and sheer wonder of your blessing arrayed before us in all its dazzling, brilliant diversity. There are differences among us. Most of them are keen and beautiful. Some of them are deep and painful, and they all matter. But none of these differences need be as important as the difference you can make with what you have gained here. None of them need matter as much as the difference you could be to all you have worked for and all you will stand for, through all you have been and all you will become.

Those of us on this stage have the world’s best view, because we see all of you, we see all you have been through, and we see all the goodness in you too. Beyond this Yard we see a world in desperate need of goodness. We see a world in need of you. Our trying times have not ended. But you’re not finished yet either. There is much yet to be done, but there is also much that you have left to do. And the task of getting it couldn’t fall to a better–or better prepared–group of people.

Harvard class of 2024, in so many ways you have made us proud. Make us proud again. I bid you every blessing, today and always. Now go in peace to become for our world the blessing you have been to us. Amen.

The sheriff then returned to the fore, staff in hand, to shatter the contemplative mood and adjourn the proceedings at 11:55 a.m. The timing was good: the day having grown cloudy and thick, rain began coming down hard 10 minutes later, and the thunder from the stage having quieted, the weather gods—happy with Harvard or not—unleashed real thunder from the gray skies above.

• • • • •

Check back at www.harvardmagazine.com for continuing coverage of:

• Radcliffe Day, May 24, honoring Sonia Sotomayor, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States since 2009 and the accompanying panel discussion; and

• Harvard Alumni Day, May 31, with actor, producer, and writer Courtney B. Vance ’82 as guest speaker.