When Lawrence S. Bacow was elected the University’s twenty-ninth president in February 2018, the Corporation—on which he had served since 2011—and the Board of Overseers were confident that they had chosen the right person to keep the lights on: an experienced leader, familiar with Harvard, who could take charge promptly at a “pivotal moment for higher education.” What they could not know was that they had also found the perfect person to turn the lights off: to sustain the academic mission while protecting community members during the COVID-19 crisis that shut down residential education and research during his second year in office. Bacow’s presidency, concluded this June 30, will deservedly be remembered for his sure handling of the pandemic amid uncertainty and fear. But recalling his five-year tenure only for that sells Larry, as he insists on being called, far too short.

A different kind of remote work: the new president settles in at Loeb House on his first day, July 2, 2018, while Massachusetts Hall was under renovation.

Photograph by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

A Fast Start

It can be hard to remember Bacow’s fast start from July 1, 2018. Operating without benefit of the usual presidential residence (Elmwood was under renovation) or office (ditto Massachusetts Hall—perhaps a harbinger of the pandemic exile from campus), he plunged into an extensive, global array of activities. Beyond meeting with community members in Cambridge and Boston (“This was a year in which I learned a lot about Harvard,” Bacow said in June 2019) and participating in forums and events at most of the schools, the very peripatetic president visited alumni and others in Detroit, New York, San Diego, Miami, Phoenix, Houston, and Chicago. While showing the flag, he also conveyed a humbler tone for Harvard by showcasing its scholarship and graduates in service to society: a deliberate response to public dissatisfaction with higher education and a reflection of his institutional values.

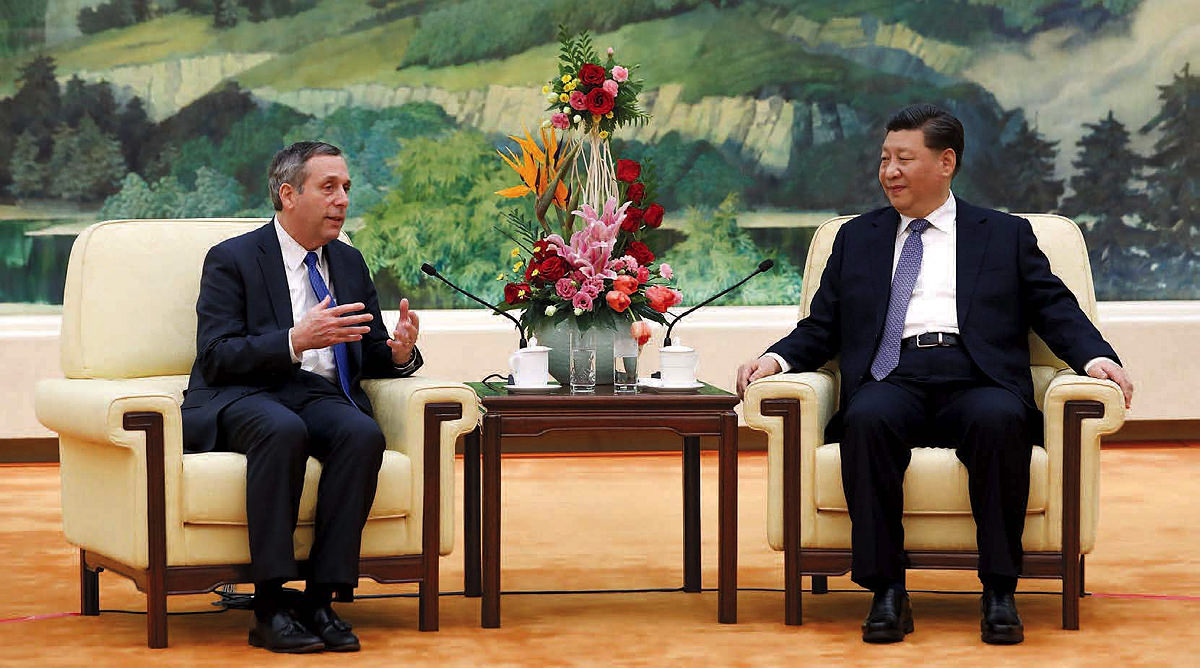

The first winter, Bacow dropped by London en route to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, followed by March stops in Hong Kong and Tokyo bracketing an official visit to Beijing (where he met with President Xi Jinping) and then Shanghai. Such visits were hardly pro forma. In the People’s Republic, for example, he made the case for academic freedom during a speech at Peking University, referring to both the centennial of the liberalizing May Fourth Movement and a verse by the late Uyghur poet Abdurehim Ötkür (a reminder of the Muslim people under severe repression in western China): essential but not easy messages to deliver given China’s deepening authoritarianism.

Global presence: President Bacow meets with China’s President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People, in Beijing, on March 20, 2019.

Photograph by Andrea Verdelli/Pool/Getty Images

Recognizing higher education’s political challenges, Bacow made seven trips to Washington, D.C., meeting with dozens of members of Congress plus administration officials. Citing the critical relationship between the academy and the federal government established during World War II, he said, “Every so often that partnership is examined, reconsidered, and in some cases, reconstituted.…It feels like this is one such moment,” when “Harvard needs to be an important part of that conversation.” Bacow joined the board of the American Council on Education, whose 1,700 members include two- and four-year degree-granting institutions, public and private. “We can’t afford to be seen as standing apart” from community colleges and other entities, he said. “We are all part of the broader community of higher education.” He championed the educational value of diversity as the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuit (against the College’s use of affirmative action in evaluating applicants) proceeded through trial, and attended the closing arguments in Boston.

Putting these travels and events in some perspective, it is also important to note that Bacow chose not to pursue many typical paths during his first 18 months. Instead, he worked on several underlying priorities that would become the consistent themes of his presidency.

At home in the heartland: President Bacow—accompanied by Graduate School of Education Dean Bridget Terry Long and Adele Fleet Bacow—meets assistant principal and lead robotics coach Greg Spencer touring the International Technology Academy in Pontiac, Michigan (his childhood home), on September 13, 2018, during visits there and in Detroit showcasing Harvard’s domestic interests and impact.

photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

Elements of Style…

The president made appointments to fill vacancies, choosing Claudine Gay as Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) dean in July 2018 and Brian K. Lee as vice president for alumni affairs and development in September, succeeding incumbents who completed their service as Drew Gilpin Faust’s presidency and the Harvard Campaign concluded. Beyond that, he organized his Mass Hall team, including Patti Bellinger, a substantive chief of staff, and new processes for coordinating the work of deans and senior administrators. Because he had already worked with Lee (during Bacow’s Tufts presidency) and Bellinger, neither appointment entailed a learning curve about their boss’s operating style. The provost’s role became more prominent, too. Those decisions made, he did not bring in his own provost, executive vice president, or other vice presidents: a set of searches and changes that could have consumed much of the first year or two of his already busy term.

Given the completion of the capital campaign on June 30, 2018, there was no need to start planning the next fundraising effort, an enormous demand on any university leader’s time. The continuing flow of nine-figure gifts (for the FAS, Medical School, Wyss Institute, and a new American Repertory Theater in Allston) provided assurance about Harvard’s access to resources. And significantly, Bacow’s administration took no visible steps toward a campaign during his presidency: a strong indication that in coming out of retirement to accept the job, he did not intend to serve for the decade or so that executing a fund drive would require.

Consistent with those decisions, Bacow also established a restrained operating style. He weighed in on matters important to the University in Washington and elsewhere. But he deferred to others on matters where his say-so was not essential, and appointed committees to devise or update policies on harassment and bullying behavior, gifts to Harvard, proposals to rename facilities and professorships, and so on—broadening the perspectives considered, but also removing much of the policymaking minutiae from the president’s immediate agenda.

It would be accurate to describe such choices as the personal preferences of a constitutionally modest leader who had, throughout his career at MIT and Tufts, included others and shared credit for their institutions’ successes.

Hands-on helpers: the Bacows schlep stuff during first-year move-in on August 27, 2018.

Photograph by Jon Chase/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

… and Strategy

But limiting his role in those ways also enabled Bacow to advance aims important to his vision of the University and the potential of his presidency. First, he encouraged more collective responsibility for running a notoriously decentralized institution. Second, he freed time and space to pursue his substantive agenda for Harvard. Both would prove valuable when COVID-19 sundered University routines.

Bacow set a few big goals and set about making progress in an organization where it can be difficult to get stuff done.

During his second winter at Tufts, Bacow had articulated a strategy focused on need-blind undergraduate admissions to attract the best students, better compensation for and more aggressive hiring of the best faculty members, and belt-tightening elsewhere and a capital campaign to pay for the upgrades. He never explicitly laid out a similar recipe for this community, but in retrospect it is clear that he pursued several aims from his earliest months at Harvard’s helm. (This list is an artifice—presidents are involved in everything—but it corresponds to Bacow’s fundamental focus on setting a few big goals and making progress in an organization where it can be difficult to get stuff done.)

• Allston. In November 2018, citing campus development across the Charles River as “Greater Boston’s next epicenter of research, discovery, and innovation,” Bacow created the Harvard Allston Land Company “to speed progress toward that goal,” separating commercial development of the 36-acre enterprise research campus facing the Business School across Western Avenue from subsequent academic or other use of additional University properties. By late 2019, HALC had chosen Tishman Speyer as developer.

• Continuing business: climate change, the legacy of slavery. Before the end of that year, Bacow had also chartered a Presidential Committee on Sustainability and funded an Initiative on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery, pursuing work with faculty involvement on two issues of long-term interest within the community.

Faust had weathered criticism from advocates of divesting fossil-fuel investments that might be held within the endowment—and despite the University’s intellectual resources, the Harvard Campaign didn’t yield an overarching program on climate change. Bacow met with divestment advocates (and experienced their disrupting his speaking engagement at a Kennedy School forum—an absolute anathema to someone who is a staunch free-speech advocate, as he made clear) and listened to FAS debates leading to a pro-divestment vote in early 2020. But he also set about redefining the climate-change issue to craft academic solutions he deemed better aligned with the University’s mission.

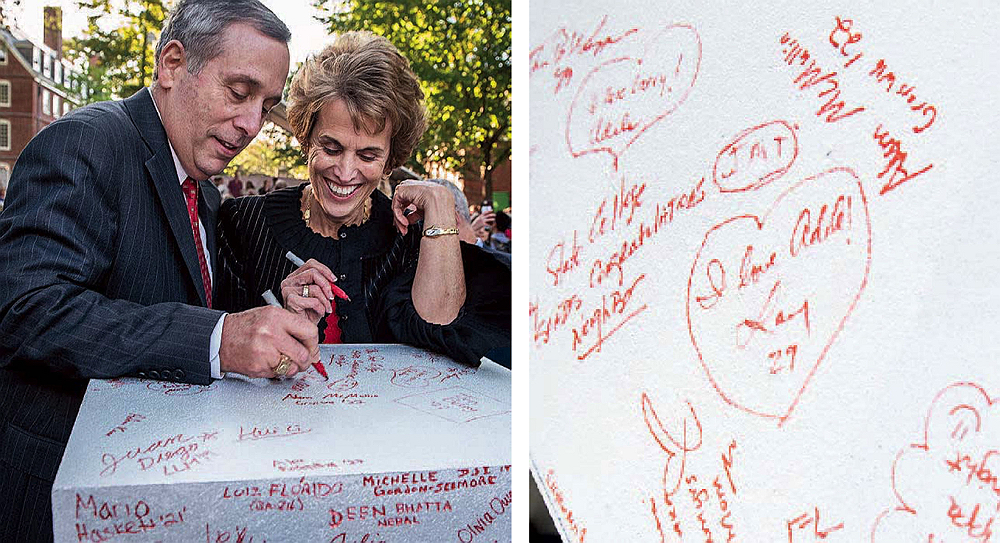

Larry 29 and Adele make their mark at the Old Yard party following his installation, October 5, 2018.

Photographs by Jim Harrison

Similarly, building on prior research on Harvard’s history of engagement with slavery and Faust’s formal recognition of that legacy in 2016, Bacow sought a deeper accounting of what had happened and a comprehensive response. Those tasks became far more urgent the following spring when the murder of George Floyd set off a national reckoning with race.

• Academics: applying science. Those initiatives aside, research and teaching are Harvard’s reason for being—and it is here that the most significant impact from Bacow’s agenda may emerge. In a conversation this past February with Ruth Simmons, Ph.D. ’73, LL.D. ’02 (now president emerita of Prairie View A&M, her third presidency), Bacow said academic leaders “have to be willing to…look over the intellectual horizon and identify whole fields or disciplines that are going to be…more important in the future than they might be today.”

He practiced what he prescribed. During a first-year trip to Silicon Valley, he and faculty experts met with industry leaders to discuss digital technology and social concerns such as privacy, ethical use of algorithms, and the future of work: a first step toward building a presence in artificial intelligence. That fall, Bacow also announced the Harvard Quantum Initiative to foster research in quantum science and engineering among FAS and School of Engineering and Applied Sciences faculty members, along with partners (at MIT and in industry). He later described the program in startlingly ambitious terms, drawing a comparison to the life sciences in the 1970s, when he began his faculty career at MIT and scientists had “just started to explore our capacity to sequence and edit the genome”—work that now underlies “therapies, drugs, and whole new industries.” In the quantum realm, he said, scientists were on the verge of exciting discoveries, leading to wholly new uses and businesses.

In AI and quantum engineering, institutions like Stanford and Carnegie Mellon had established important footholds and MIT and Caltech have significant strengths, but Harvard’s presence was nascent. Moreover, the greatest potential for both lay in their applications—as technologies: the realm where the University, despite investments during the past 15 years, has a shorter history and fewer clear advantages than it enjoys in basic life and biomedical sciences. Bacow set about to change that.

With an agenda set during a busy freshman year and sophomore fall semester, it seemed that his administration had established its rhythms. He had long since resumed operating out of Mass Hall, had moved into Elmwood in April 2019, and was well along in fleshing out his initiatives. On the other hand, he reflected that spring that at Tufts he had found “every year was unto itself, often shaped by circumstances that could not be foreseen at the beginning of the year” (he became president there in 2001—10 days before the 9/11 attacks). A leader can plan, he said, but not predict.

COVID Comes

On the morning of March 10, 2020, Bacow informed the community that in-person teaching would be suspended, and students “are asked not to return to campus after spring recess and to meet academic requirements remotely until further notice.” By then, the novel coronavirus that burst out of Wuhan had devastated communities in northern Italy and spread into international gateways like Seattle and New York City—with Boston not far behind. Harvard scientists knew the risks of a lethal respiratory pathogen that spread asymptomatically; the China Evergrande Group had pledged $115 million to the Medical School and an institute in Guangzhou for research on the threat and possible therapies.

Weighing the inconvenience versus the potential loss of lives, Bacow described the decision to close campus as not difficult.

Bacow later described his decision as not difficult: if dispersing people from campus proved unwarranted, the costs could be tallied in inconvenience and dollars—but erring in the other direction potentially threatened thousands of lives. Harvard’s action, among the earliest by a major university, proved prescient—a wave that swept across higher education, early in a month when much of society ultimately shut down.

After that decision, a grinding succession of others followed, as laboratories were shuttered, professors and students pivoted to Zoom, and financial analysts worried about maintaining a campus and its employees absent the usual revenues. On March 20, three days before virtual instruction was to begin, the president communicated another decision, in an empathetic voice that became familiar: “I love commencement,” he began, continuing:

I love seeing our community come together to celebrate the academic accomplishments of our remarkable students. I love seeing their families brimming with pride as they participate in a ceremony that is almost as old as the University itself.…

So it is with an especially heavy heart that I write to inform you that our 369th Commencement Exercises, which would have taken place on Thursday, May 28, must be postponed. Given the advice we are receiving from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, other public health officials, and our own faculty, who are among the world’s leaders in infectious disease, epidemiology, and virology, it is difficult to imagine how we could safely hold such a large gathering this spring.

He made two critical promises: that Commencement would only be “postponed,” and in the meantime, a virtual degree-conferral event would ensure timely graduation.

Pandemic president: filmed outside Massachusetts Hall for the second online graduation exercises, May 27, 2021

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

One day into online teaching, on March 24, Bacow—who is immunocompromised—wrote again to relate that he and his wife, Adele Fleet Bacow, had tested positive for COVID-19. As they isolated, he turned the focus away from himself:

Your swift actions over the past few weeks—to respond to the needs of our community, to fulfill our teaching mission, and to pursue research that will save lives—have moved me deeply and made me extraordinarily grateful and proud. I hope to see as few of you in our situation as possible, and I urge you to continue following the guidance of public health experts and the advice and orders of our government officials.

The world needs your courage, creativity, and intelligence to beat this virus—wishing each of you good health.

All the best,

Larry

That tone helped keep the community on an even keel during the trying months that followed. The 2020-2021 academic year proceeded with most instruction conducted remotely, strict PCR testing regimens, and isolation procedures and in-room dining for the few resident undergraduates. The libraries began delivering books from the stacks; the College distributed technological tools to students who needed them and sent course materials for experiments to learners at their homes. In emailed updates—signed by Bacow; Alan Garber, the provost (a physician); Katie Lapp, executive vice president; and Dr. Giang T. Nguyen, executive director of Harvard University Health Services—the president and his senior colleagues modeled collaboration and urged fellow Harvardians to assume responsibility for their common health.

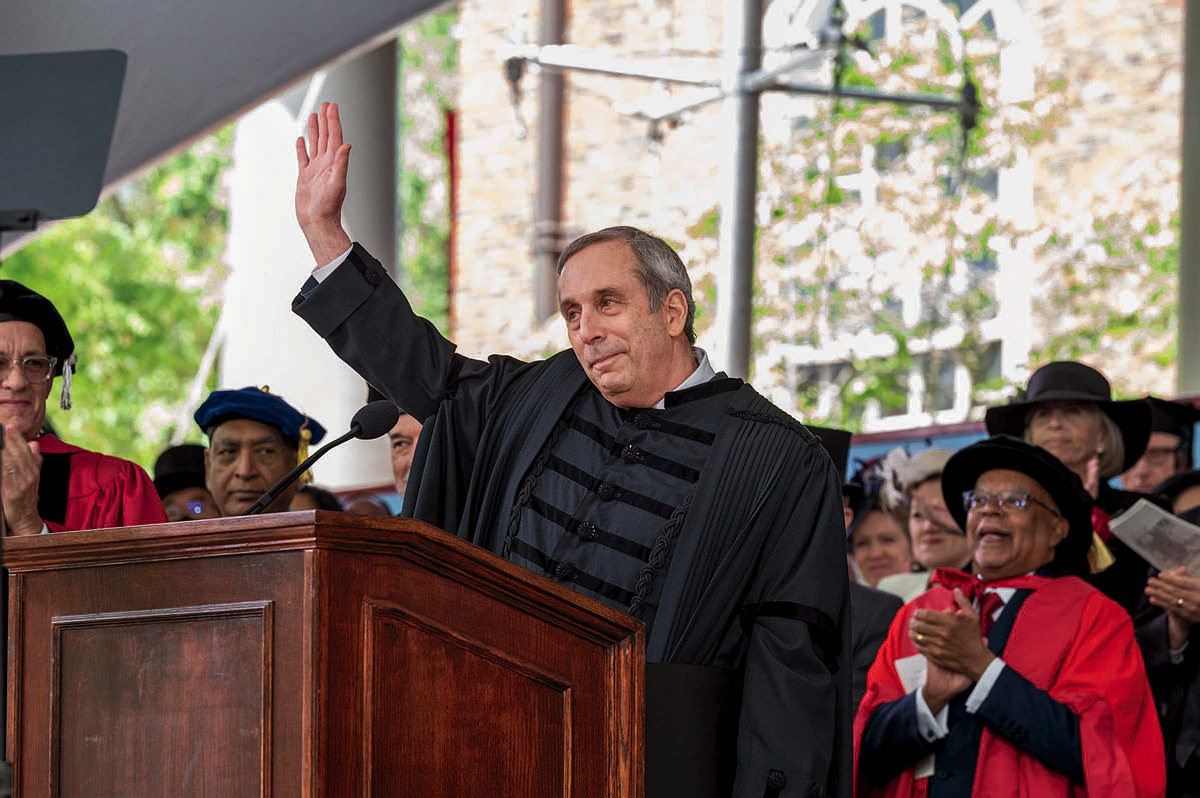

There were emotionally resonant moments (the virtual Harvard University Chorus rendering “Fair Harvard” at the end of the ghostly 2020 online graduation) and memorably funny ones (during the more elaborate 2021 ceremony, Bacow, filmed in his presidential gown at a lectern beside Massachusetts Hall, observing that he was outside his office, “where I haven’t been for 440 days—and counting”).

The cathartic declaration that the University had come thro’ this severe period of change and storm came on May 26, 2022, with a 371st Commencement extravaganza for the class of 2022 and, as promised, an even larger “Commencement celebration” three days later when alumni of 2020 and 2021 embraced classmates, whooped it up with families and friends, and reveled in the fact that they had made their way through Harvard and, literally, lived to tell the tale. A tribute to those who served during the pandemic was the fitting centerpiece of the unique (fingers crossed) event. U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland ’74, J.D., ’77, the guest speaker, aptly summarized the weird context for the Sunday throng: “I know it must be a bit strange to be back here: not as soon-to-be graduates anxious about the future but as actual graduates—anxious about the future.”

Hoopla aside, it became clear that Harvard had learned some valuable lessons. Professors who had conducted online courses through the Harvard-MIT edX venture and the staff who supported them became essential emissaries as every teacher abruptly pivoted to remote instruction. Not everything was perfect, but a lot went right. Whole faculties were exposed to new pedagogical ideas and found they could embrace change. With sponsored research restored promptly, burgeoning interest in online Extension School classes, and rapid remaking of executive education in virtual formats (and absent many routine expenses, like travel), the University found it could operate very well indeed, producing record budget surpluses and hinting at future economies from increasingly hybrid staff work.

To accommodate the Graduate School of Education’s one-year master’s program, the University authorized its first online (as opposed to in-residence) Harvard degree—with favorable academic results. Drawing on the work of scores of professors involved in pandemic planning and response, the FAS’s Claudine Gay launched an ambitious effort to engage the whole faculty in reviewing its structure and finances, aiming to fashion a common vision for its academic future. And so on.

Post-Pandemic Progress

After joyful Commencement reconnections and reunions at the first Harvard Alumni Day on June 3, 2022, President Bacow chose the following Wednesday, June 8, to announce that he would step down on June 30, 2023, at the end of what everyone hoped would be a truly new-normal academic year.

Such deadlines concentrate the mind. The decks cleared of pandemic exigencies, Bacow could devote his energies to the priorities he established B.C. (Before COVID). Perhaps surprising those who were understandably distracted during the pandemic or mourning the losses it caused, he had seen to it that Harvard made progress on all of them.

Five weeks after he disclosed his plans, Boston regulators approved the 9.4-acre, 900,000-square-foot first phase of the enterprise research campus in Allston. That reflected the sustained efforts of Tishman Speyer; Jeanne Gang, M.Arch. ’93, who designed the project; Mayor Michelle Wu ’07, J.D. ’12, who pushed for more affordable housing; and the administration, represented by Katie Lapp. Although current economic conditions may delay construction, securing approval is a big deal, and Harvard is about to build the University conference center that is the front door to the development. Meanwhile, the proposed new American Repertory Theater on North Harvard Street (with an accompanying affiliate-housing tower) is under regulatory review. With the 2021 completion of the long-delayed engineering and applied sciences complex on Western Avenue, Harvard in Allston has moved from the realm of imagination toward the campus expansion and other development that have been bruited about for nearly four decades.

Bacow’s response to sustained lobbying for divestment of any fossil-fuel investments—including two Overseer elections with petition candidates running successfully on a divestment platform—proceeded toward a comprehensive Harvard climate program.

In April 2020, he announced that the endowment would become “greenhouse-gas neutral” by 2050, achieving “net zero” emissions, taking into account both production of fossil fuels (the focus of divestment) and consumption. The following February, Harvard Management Company’s (HMC) first climate report disclosed “no direct exposure” to companies that explore for or produce fossil-fuel reserves and externally managed investments in those sectors amounting to less than 2 percent of endowment assets. In September, Bacow advised the community that “HMC does not intend to make” direct investments in such companies and that the remaining external holdings would be run off HMC’s books—de facto, a kind of divestment, without formally adopting a policy to that effect or invoking the term. On the other side of the ledger, he reported, HMC had begun investing in funds that “support the transition to a green economy.” Of perhaps greatest consequence, he appointed Burbank professor of political economy James Stock, an environmental economist with high-level policy experience in Washington, D.C., to a new post, vice provost for climate and sustainability.

President Bacow and James Stock, vice provost for climate and sustainability, at the Salata Institute symposium, May 9, 2023

Photograph by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

Then, less than two weeks after unveiling his retirement plans, Bacow announced a $200-million gift for the Salata Institute, a University focus for research, teaching, and outreach on climate change led by Stock—elevating work in the field to a new level.

The project on slavery, led by Tomiko Brown-Nagin, a legal historian who is the Radcliffe Institute dean, proceeded in a more academic fashion but yielded a similar commitment to large-scale action across the University. The report on “The Legacy of Slavery at Harvard,” published April 26, 2022, was a deeply researched scholarly inquiry (111 pages of footnotes in the Harvard University Press edition) into what Bacow summarized as “truths long obscured: that enslaved people worked on our campus; that the labor of enslaved people enriched donors and, ultimately, the institution; that members of our faculty promoted ideas that gave scholarly legitimacy to concepts of racial superiority; and that the University continued discriminatory practices long after the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified in 1865.” The report’s recommendations were backed by an endowment of $100 million from University funds, endorsed by each Corporation member. Those resources are already yielding efforts to memorialize those enslaved and identify their descendants, teach what has been learned, and create partnerships with historically black colleges and universities (with advice from Ruth Simmons), perhaps even extending to student and faculty exchange programs. The aim, he wrote, was “to understand how we as a community might redress—through teaching, research, and service—our legacies with slavery”: a program of action suited to an academic institution but not a debate about public policies like reparations.

In Texas, on February 27, 2023, President Bacow and Prairie View A&M President Ruth Simmons discuss the legacy of slavery initiative—and her role in implementing its recommendations.

>Photograph by Nicholas Hunt/Prairie View A&M University

The initiatives on quantum science and artificial intelligence technology presented a more familiar challenge: how might someone secure a lot of money so professors and students could do something intellectually new and exciting? In that capacity, even absent a campaign, Bacow proved himself a peerless rainmaker.

By the time the 2018 quantum initiative had fledged a Ph.D. program in quantum science and engineering in April 2021, funding was in hand to transform a 94,000-square-foot building into a purpose-built research facility, with Stacey L. and David E. Goel ’93 (the backers of the ART project) as lead donors. The first student cohort enrolled in the fall of 2022, and this past March Bacow underscored the program’s intellectual prowess by elevating physicist Mikhail Lukin, one of its leaders, to the Friedman University Professorship: Harvard’s highest faculty rank.

The work on AI launched even more spectacularly, in December 2021, when Facebook co-founder and Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg ’06, LL.D. ’17, and his wife Priscilla Chan ’07 made a $500-million commitment over 15 years to underwrite the Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence (named after his mother). The institute will support 10 new faculty appointments, dozens of fellowships, computing infrastructure, and more. Again, the initiative was anchored in senior faculty leadership: the Medical School’s Moorhead professor of neurobiology Bernardo Sabatini and McKay professor of computer science Sham Kakade, newly recruited for the role from the University of Washington.

Both programs thus began with sufficient start-up financial and intellectual capital to progress toward Bacow’s goals of ensuring significant discoveries from Harvard labs and growing cohorts of Crimson experts in promising new fields. They also underscore the direction of his most intentional fundraising. Combining the Kempner and quantum support, a share of the Salata Institute’s likely research grants, the $200-million gift to the Medical School, and continuing philanthropy from Hansjörg Wyss, M.B.A. ’65, for his eponymous bioengineering institute (nine-figure gifts in 2019 and 2022), Harvard has received about $1.2 billion in cash and pledges for applied science since mid-2018: a powerful sign of where the academic enterprise is headed.

Institutional Intelligence

Each of these achievements is a hallmark of Bacow’s presidency. But their collective import—what they say about running a place like Harvard today—may matter even more as the University contemplates its role as it approaches its four-hundredth anniversary in 2036.

The president speaks often about listening well and learning from others—and living up to one's responsibilities

Bacow’s leadership style might be deemed anti-imperial. He routinely deflects credit from himself to others. At Morning Prayers and in Commencement addresses and his columns in this magazine, he speaks often about the virtues of listening well and learning from others, and about living up to one’s responsibilities. His community missives are plain-spoken and personal: people who have never met him know something about his parents’ immigrant experiences, his wife Adele, their children and grandchildren, and the sustaining importance of his Jewish faith. As someone who found his life’s work in higher education when he enrolled at MIT in 1969 and never left, he is devoted to scholars’ accomplishments but restrained in talking about his own academic work (despite an MIT degree and three from Harvard)—not least because he crossed over into the realm of leadership as MIT’s chancellor in 1998, two decades before he answered the Harvard Corporation’s call. People approach him less as President Lawrence S. Bacow than as Larry, a mensch who radiates empathy.

But alongside that evidence of emotional intelligence, other factors explain how this naturally modest figure has become a revered leader throughout higher education: the successful president of both Tufts and Harvard (whose high profile and enormous wealth may make the job in some ways even more difficult).

There is, in fact, a through line from Bacow’s Harvard graduate studies to his imprint on the place from Mass Hall. “The Pragmatist,” this magazine’s profile of the new president (September-October 2018, page 32), described his doctoral research. Bacow analyzed occupational safety and health from the perspectives of regulatory rulemaking (“a convenient forum for the presentation of alternative viewpoints [but] not well structured to resolve the differences”) and bargaining over the real-world application of safety standards (where he found gains from actively engaging “the parties most directly affected”). More broadly, he observed of the entities he studied: “Institutions tend to be organized to perform the tasks they are currently performing. Their capacity to perform new tasks is limited. Moreover, they learn slowly and can only pay attention to a few things at a time.”

Refined into a 1980 book, those lessons emerge as a theory of action rather than an unending search for (unobtainable) perfect outcomes: negotiation “will not be as efficient as the decentralized intervention strategies urged by many economists, but it will be more efficient than what we have now.” Other work, like the co-authored Facility Siting and Public Opposition (1983), addresses concerns such as compensating parties and building effective coalitions to achieve desirable ends. Retrospectively, it seems inevitable that the academic analyst of decision-making in difficult settings would become a practitioner of those arts in long-established, multipolar enterprises that meld research, professional training, and residential undergraduate education.

In this light, the accomplishments outlined above look like the products of classic Bacow craft. The Allston enterprise zone gained political approval only after he focused on a feasible commercial project rather than something vaster, and because the University and developer then agreed to benefits requested by neighbors—crucially including twice as many affordable housing units as Boston typically requires. Those same skills were also on display within the University. It took some combination of cutting Gordian knots and threading needles to progress from a stalemated divestment debate to a robust academic program on climate change and sustainability. That was the case for the research on slavery, too.

In both instances, of course, huge cash infusions helped (this is Harvard). But the outcomes proceeded from the president’s work in defining the problems to be solved, engaging interested parties, and creating a context for subsequent action. At the Salata Institute’s May symposium, James Stock said that although the University had a strong environmental studies community, “Larry recognized that, given the pressing nature of climate change, Harvard needed to do more.…[H]e realized that the key for Harvard doing more on climate was to make it a University-wide priority, not just the domain of any single Harvard school”—leading to the vice provostship, the institute, and now burgeoning efforts to “influence the world…through our research and teaching.” In short, “If not for Larry’s leadership, we would not be in this room today.”

In selecting Bacow, the Corporation found a president with remarkable capacity for advancing the University internally.

The term for this might be institutional intelligence. As it turns out, in selecting Bacow because of its anxieties about the external environment for higher education, the Corporation also found someone with remarkable capacity for advancing the University internally. And in his readiness to make decisions quickly and change course when needed, Harvard got lucky in the dark late winter and darker early spring of 2020.

There are plenty of other things to say about the Bacow presidency. As someone whose life was indelibly shaped by his mother’s flight from Nazism and immigration to the United States, he was an outspoken advocate for international students, immigrants, and refugees—notably so when the Trump administration sought every avenue to restrict access to this country and its universities. Similarly, he responded to the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Russian attack on Ukraine by expanding support for the Scholars at Risk program. Collectively, he called these actions his proudest accomplishment as president.

A proponent of the educational and other benefits of diversity (he frequently tells audiences that talent is distributed equally, but opportunity is not), Bacow made executive appointments—from the University’s health services and the vice president of human resources to the campus police and the Memorial Church ministry—that literally changed the face of Harvard. He reminded the community repeatedly about the foundational value of free speech, especially at a moment of extreme political polarization—and the University has been free from the abuses and violations that have tarred other outstanding institutions in recent years. As a fiscally prudent president, he was able to ensure that schools under pressure early in the pandemic got the critical support they needed. The recent budget surpluses and historic 2021 gains in the endowment (essentially untapped) are an invaluable bequest to his successor, who can set initial priorities without the immediate pressure of turning to the next capital campaign.

Presented with the opportunity to change institutional norms, he did so in what he perceived as Harvard’s best interest. Emerging from the pandemic, many alumni were disappointed to see reunions severed from Commencement—but swelling crowds made the logistics increasingly fraught: consider the 9,100 graduates and their guests this May. The new exercises, focused on the graduates and integrating the guest speaker’s address into the morning festivities, make evident good sense. (It is not coincidental that Bacow, who has attended perhaps four dozen graduations, had strong ideas about how to proceed.) When he and the Corporation perceived that the success of the Harvard Forward candidates for the Board of Overseers challenged tenets of what they considered good governance, they changed the rules for how many petitioners could be elected: a broadly unpopular decision, but one he regards as completely consistent with enabling the University to persist and succeed over time. And when Bacow finally concluded that having the president chair FAS meetings made no sense (and could present problems for the next dean, since Claudine Gay would become president), he told the professors he was ending the tradition.

Finally, although it could not have been foreordained, it is hardly surprising that this mentor of up-and-coming academic leaders chose Gay to lead FAS—and gave her the experiences and opportunities that helped the Corporation quickly decide that she should become Harvard’s thirtieth president.

* * *

Larry Bacow didn’t need the Harvard presidency and didn’t seek it. He had had a successful, fulfilling career, and accepted the appointment out of a sense of duty to higher education. Other Harvard presidents will take the office with different motivations, and none will have the same personality. But any future president of this or comparable schools could learn plenty from his theory of leadership: how to manage the torrent of daily demands while defining major challenges effectively and focusing on a few priorities that might make a real difference to their institutions’ futures.

From the Corporation’s perspective, Bacow checked all the boxes. In their statement accompanying his retirement announcement, the departing and arriving senior fellows, William F. Lee and Penny Pritzker, said, “[H]aving watched him lead Harvard these past years—with great inner strength, a steadfast moral compass, and a deep devotion to serving others—we have come to admire him all the more.”

Among his other accomplishments, they cited: pandemic leadership; focus on advancing intellectual priorities; support for educational innovation and the extension of Harvard’s teaching to learners beyond the physical campus; continued renewal of University physical facilities and stewardship of its financial resources; actions to make the community more inclusive; encouragement of “candid, mutually respectful discussion of difficult issues among people with different points of view” within the community; continued emphasis on the University’s role in bettering the wider world; and “by word and deed,” Bacow’s role in helping every member of the community “reflect on how we can direct our energies toward causes larger than ourselves.” Noting his insistence on crediting colleagues for Harvard’s accomplishments, they continued, “[G]reat teams rely on great captains. And—through the tone he sets, through the values he affirms, through the common purpose he cultivates, through the trust he builds, through the initiatives he launches and sustains—Larry Bacow is just that.”

In a community where success is celebrated and privilege is too often taken for granted, members of the community at large might retain an impression of Bacow’s purposes and impact from hearing his own words. In his welcoming remarks at the 371st Commencement, in May 2022, Bacow riffed on the pandemic supply-chain issues that nearly resulted in the University having too few chairs on hand to seat everyone present—“likely the last time you almost didn’t get a seat.” He then pivoted to talk about the Harvard culture he hoped to inculcate:

Soon you will have a degree in hand from an institution whose name is known no matter where you go in the world, whose name is synonymous with excellence, ambition, and achievement—and maybe some other modifiers on which we needn’t dwell today.

With your degree…you may often find yourself invited to sit and stay awhile, invited to share your thoughts and ideas, invited to participate, to contribute, to lead. You may end up sitting on a board or occupying a seat of power.…

And what are you to make of that—of the fact that people will make room for you, find a seat for you?

You could take it for granted. You could assume that you deserved it all along.

But what a waste that would be.

Today, I want to challenge you…to save a seat for others, to make room for others, to ensure that the opportunities afforded by your education do not enrich your life alone.…Whatever you do with your Harvard education, please be known at least as much for your humility, kindness, and concern for others as for your professional accomplishments. Recognize the role that good fortune and circumstance have played in your life, and please work to extend opportunity to others just as it has been extended to you.

That is how you will sustain the pride and joy you feel today. And that’s the truth.

As President Bacow returns to retirement—to more time with Adele Fleet Bacow and their grandchildren (two born during this presidency) and to reading books and traveling for pleasure—what better thing to say than, “Larry, all the best.”

A fond and fitting farewell: Larry Bacow after concluding his final Commencement remarks, May 25, 2023

Photograph by Jim Harrison