Harvard’s annual financial report for the year ended June 30, 2022, published today, reflects a University that has returned robustly to full operation, after residential instruction was suspended from March 2020 through the following academic year, but with expenses still constrained. The result is a record current surplus, but the endowment declined in value. Among the highlights:

• The University recorded a $406-million operating surplus, up from $283 million in fiscal 2021. Adjusting for one-time items recorded in fiscal 2020, the accumulated black ink for the three years shadowed by COVID-19 totals more than $900 million: an astounding sum, compared to fears at the inception of the pandemic that Harvard faced multi-hundred-million-dollar declines in revenue, and enormous losses.

• The endowment—following a spectacular $11.3-billion gain in value in fiscal 2021, fueled by a generational 33.6 percent investment return on assets—came down to earth in the most recent period. Harvard Management Company (HMC), which oversees investment of the assets, reported a negative 1.8 percent return, as inflation and rising interest rates pummeled many categories of assets.

• Those investment losses, combined with the $2.1 billion distributed to Harvard’s operating budget (offset in part by gifts received), reduced the value of the endowment by $2.3 billion, from $53.2 billion in fiscal 2021 to $50.9 billion as of this past June 30: a decline of 4.3 percent.

Black Is the New Crimson

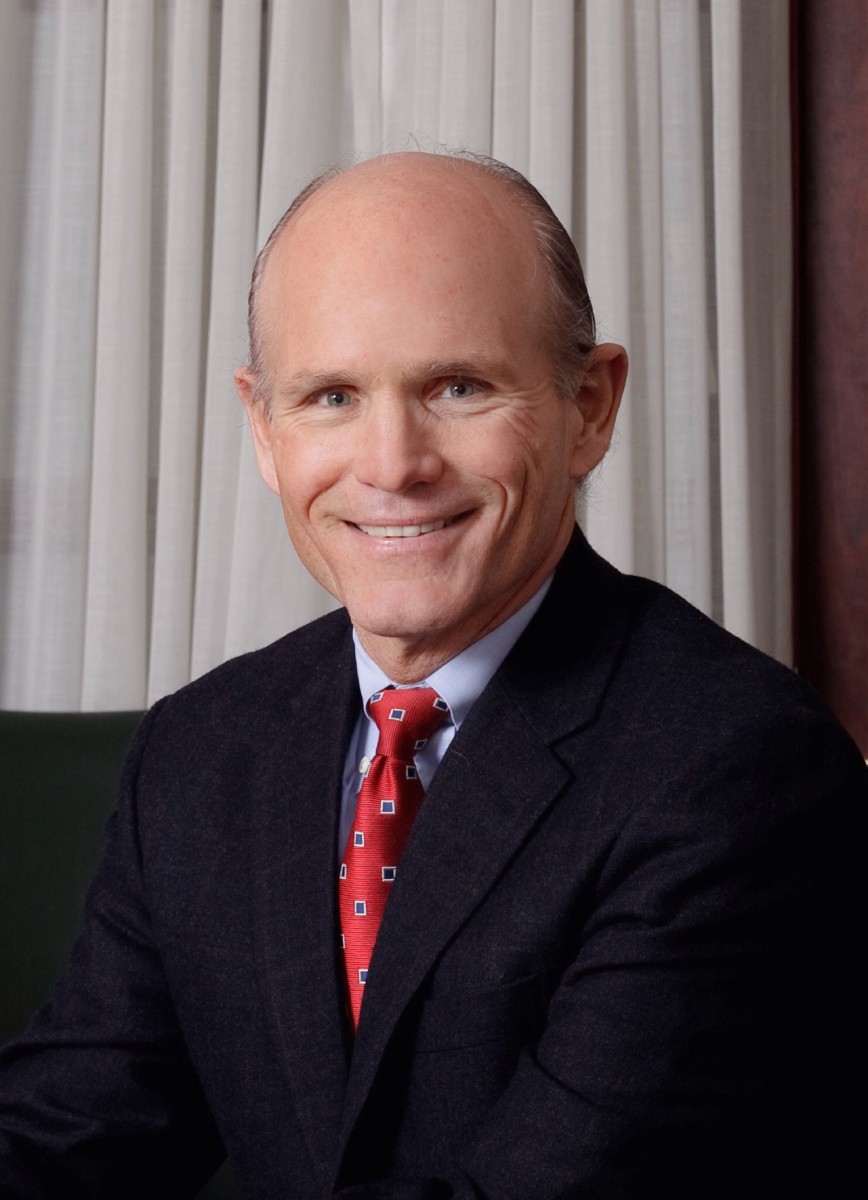

In their annual letter to readers, vice president for finance and chief financial officer Thomas J. Hollister and University treasurer Paul J. Finnegan write that in the wake of the pandemic, “Revenues this past year rebounded” and “Expenses rebounded as well…although rising less than revenues due to comparatively high vacancy rates in staff as well as sourcing challenges with goods and services.”

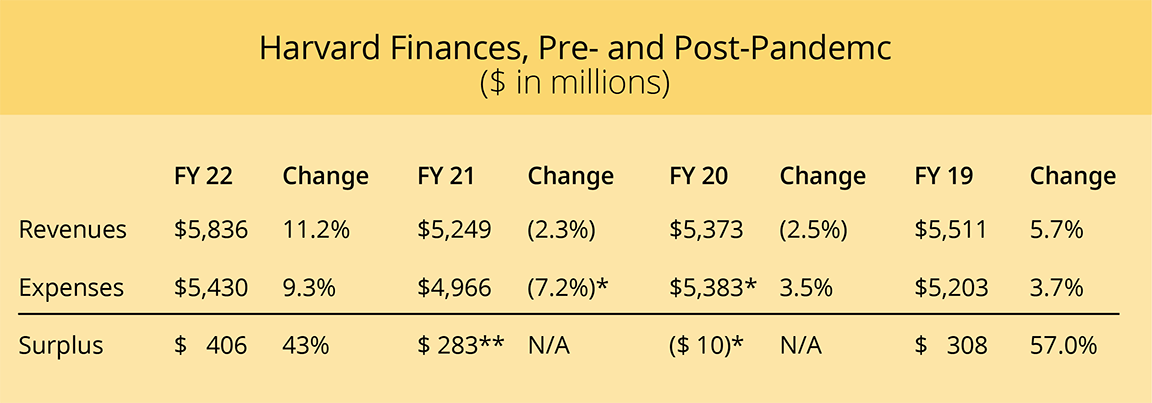

And how! Revenues rose 11 percent, to more than $5.8 billion, and expenses 9 percent, to slightly more than $5.4 billion: after two years of declines in operating revenues and expenses (see footnote below chart), both exceeded the pre-pandemic levels reported in fiscal 2019—and produced a record operating surplus of $406 million. The highlights, including percent change from prior-year results, appear below.

**If the one-time items discussed in the prior note are excluded, the FY 21 surplus would have represented an increase of more than 20 percent compared to the adjusted surplus in the prior year.

As the data indicate, fiscal 2022 revenues exceeded those in fiscal 2019 by nearly one-third of a billion dollars (up 5.9 percent) but the comparable expenses rose just $227 million (4.4 percent). Hence, the enlarged surplus. Current revenues are likely abnormally large, at least in terms of enrollment and student tuition; the principal question for Harvard’s future financial results concerns the growth of expenses in a highly inflationary environment.

Thomas J. Hollister, CFO

Paige Brown, Courtesy Tufts Medical Center

But for now, the University has seemingly emerged from the pandemic in an incredibly strong financial position. Given the recent report by Medical School dean George Q. Daley that his school had broken even following deficits each year since fiscal 2009, it is possible that for the first time in more than a decade, each school reported a surplus this past year.

Revenues. Harvard’s revenues increased nearly $600 million—more than 11 percent. Net student income (after financial aid) led the way, accounting for more than half the total increase, rising from $888 million in fiscal 2021—a year of almost entirely remote instruction—to $1.223 billion in the most recent academic year. Reason enough, perhaps, to feature students celebrating in-person Commencement, and ready to take on the world, on the cover of this year’s report (shown above).

Students who had deferred enrolling, or taken a year off, returned in force, with College enrollment rising from about 5,200 in 2020-2021 to an outsized record of 7,095 in 2021-2022 (the norm is 6,600-6,700). That propelled undergraduate tuition and fees up from $278.4 million to $390.8 million (these and following figures are at published rates, before scholarships are netted out). Graduate and professional degree students paid $652 million, up from $581.3 million. And with operations in residence, board and lodging fees recovered from a severely depressed $69.5 million in 2021 to just under $200 million. In all, full- and part-time degree enrollment was 25,510 for the year [Corrected October 13, 2022, 6:50 p.m.: 25,110 students enrolled during the 2021-2022 academic year], compared to 23,000 to 24,000 in pre-pandemic years.

Deans must be delighted by the strong recovery in continuing education and executive programs. A major source of unrestricted cash and financial growth for most Harvard schools, such operations produced $516 million in revenues during fiscal 2019, before the pandemic—and those revenues were increasing 9 percent to 10 percent annually: far faster than degree-program revenues. The pivot to remote operations in the spring of 2020 decimated in-person executive and continuing education classes, reducing revenue to $426 million that year, with further erosion, to $395 million, in fiscal 2021: a couple of hundred million dollars below pre-pandemic projections. But the swift pivot to remote learning, at Harvard Business School, the Extension School, and other schools, combined with more in-person and hybrid options of late, has prompted a swift rebound: fiscal 2022 revenues were reported as $487 million.

Sponsored support for research grew about 5 percent overall, to $976 million, with federal programs (about two-thirds of the total) increasing 3 percent, and non-federal sponsors (corporations and foundations) increasing funding by a total of 11 percent. [Corrected October 13, 2022, 6:50 p.m.: This paragraph reported incorrectly about how the University treats an enormous, multiyear research program, and indicated it was accounted for as sponsored support; it is in fact counted as current-use giving. We regret the misunderstanding that led to this misinterpretation. The passage in question read: “Major new programs—like the Kempner Institute, focused on natural and artificial intelligence, to the tune of $500 million of research support during the next 15 years—point to further growth in non-federal sponsorship.” That error aside, the University does expect further growth in non-federal research support.]

Donors, past and present, continued to buttress Harvard’s finances. Operating distributions from the endowment rose about $80 million (4 percent), to $2.1 billion, reflecting a 2.5 percent increase in the Corporation-approved distribution per unit of endowment held by each school or other recipient, plus growth in the number of units held from gifts received and other transfers to the endowment. Given the outsized endowment appreciation during fiscal 2021, the fiscal 2022 distribution resulted in a payout rate of 4.2 percent of market value, down from 5.2 percent in the prior year—even as the sum distributed rose.

But gifts for current use declined about $36 million, to $504 million (down 7 percent) from fiscal 2021. This may be nothing more than year-to-year variation. But given the importance of current-use gifts, some 9 percent of revenues, and their applicability to deans’ most immediate needs, this bears watching. Sustaining current-use giving at the half-billion-dollar level in the wake of the Harvard Campaign represents a significant source of strength and financial flexibility for the University.

Other, emerging sources of increased revenue included royalties for intellectual property. After soaring from $62 million in fiscal 2020 to $107 million the following year, they grew still further, to $152 million in the most recent period. It will be interesting to see whether the work going on in scientists’ labs across Harvard sustains this momentum, or if recent results simply reflect unusually favorable years. Other miscellaneous revenue lines snapped back from pandemic constraints, as services and rental and parking fees, for instance, collectively increased by $67 million in fiscal 2022 (up more than 36 percent): minor in the scheme of things, but still money the University is glad to receive.

A more familiar profile. The pandemic materially changed Harvard’s mix of revenues as:

• student income decreased from 22 percent in fiscal 2019 to 17 percent in fiscal 2021;

• sponsored research rose from 17 percent to 18 percent;

• current-use giving rose from 8 percent to 10 percent;

• the endowment distribution rose from 35 percent to 39 percent; and

• all other sources rose from 18 percent to 20 percent before declining to 16 percent.

That meant that the University had become significantly more dependent on what were thought of as volatile sources of revenue (current-use gifts, and distributions from an endowment corpus that has actually declined four times during the past 14 years). The unprecedented circumstances of the pandemic made the dependably stable revenue streams—tuition, room and board, miscellaneous fees—suddenly seem more precarious.

For what it is worth, fiscal 2022 went a considerable way toward restoring the old order. The burgeoning enrollments brought student income to 21 percent of revenue, with sponsored support and other income each reverting to 17 percent of revenues, and the endowment distribution and current-use giving declining, to 36 percent and 9 percent of revenues, respectively.

Expenses. Salaries and wages, which declined in fiscal 2021 (reflecting the prior-year retirement-incentive costs, delays in filling vacated positions, and a freeze in nonunion employees’ compensation), grew 6 percent in fiscal 2022, to $2.2 billion. The annual report cites wage increases, but “offset by higher than average levels of position vacancies”: an indication of the difficulty hiring in a tight labor market. According to the University, the census of faculty, staff, teaching assistants, and postdoctoral fellows was 18,524 as of this past June 30—down modestly from the size of the workforce at the end of fiscal 2019. [Updated and corrected October 13, 4:20 p.m.: The second sentence in this paragraph previously contained the parenthetical phrase “(2 percent for nonunion employees during the year, more for those covered by negotiated contracts, and promotions and other adjustments)” following the words, “The annual report cites wage increases,” which could be read to mean that the source of that information was the annual report. The information was previously reported separately from the annual report, and was in part incorrect as presented here. The correct figure for wage guidance for fiscal year 2022 was 2.5 percent, plus a year-end bonus, as explained in a community letter from President Bacow on June 7, 2021. Schools and other units may have followed separate guidance. We regret the possible confusion, and our error.]

Continuing recent experience, expenses for employee benefits grew negligibly, to $584 million. The annual report cites slower growth in medical costs than before the pandemic, and reduced long-term costs for post-retirement health and pension programs (which are essentially fully funded). The medical costs probably reflect both current conditions—continued constraints on elective care during COVID-19—and changes in health insurance instituted in the middle of the prior decade, which have helped to control utilization and reduce election of Harvard coverage by partners of covered employees.

With more people present on campus than during the prior year, fiscal 2022 costs for building space and occupancy (up 12 percent, to $354 million) and supplies and equipment (up 29 percent, to $271 million) naturally rose, as did travel (from less than $2 million to $44 million, as faculty members and fundraisers hit the road again)—but none of that spending exceeded pre-pandemic levels, the report notes. With hybrid work schedules, Zoom meetings, and more online instruction, it is possible that such costs will remain relatively well controlled.

One category of spending that declined was COVID-19 costs: $83 million in fiscal 2021, $53 million last year. With the end of routine, campus-wide testing this academic year, those savings should, thankfully, grow further in fiscal 2023.

The balance sheet and giving. During the year, Harvard issued $750 million in new bonds, including a $250-million offering of tax-exempt, certified “green bonds.” The proceeds will be used to pay for recent and future capital projects. After other debt payments and retirements, the University’s net borrowings totaled $6.1 billion at year-end, up from $5.5 billion as of June 30, 2021. The timing of the recent sales looks prescient in light of rapidly increasing interest rates: the effective interest rate on Harvard’s bonds and notes outstanding is 3.9 percent—right in line with the cost of long-term borrowing by the U.S. Treasury, the world’s standard.

In the near term, the proceeds from the bond sales helped to bolster the University’s cushion of cash on hand, held outside its general investment account. Those liquid, short-term investments totaled $2.2 billion at the end of the fiscal year, up from $1.5 billion in fiscal 2021: an extra margin of comfort should the economy fall into recession.

Capital spending, which was nearly $1 billion annually at the end of the last decade, continued to decline, to $356 million in fiscal 2022 from $410 million in the prior year. The Divinity School’s Swartz Hall and the Law School’s Lewis Law Center, both involving renovation and expansion, came on line during the year. Adams House renewal continues this year, on a stretched-out schedule, and the Weld and Newell boat houses are being refurbished.

Larger projects—graduate-student housing; the Eliot and Kirkland House renewals; rationalizing and renovating the multibuilding public-health campus; better accommodating the Graduate School of Education’s programs and people; repurposing the buildings depopulated when much of the engineering and applied sciences faculty relocated to Allston; and renewing the Graduate School of Design’s quarters and funding its expansion—all are likely to linger in the on-deck circle until later in the decade, and in some cases until the next University capital campaign. By then, perhaps as supply chains become more normal, very high inflation in construction costs may abate.

In the nearer term, the commercial enterprise research campus in Allston (including a University conference center) has been approved for construction, and the new American Repertory Theater facility nearby is in the final stages of design and permitting, so Harvard will remain an active, if not hyperactive, client for architects and contractors.

Finally, giving remained robust, despite the modest decrease in current-use gifts. Gift receipts (in which Harvard includes non-federal sponsored research grants) totaled $1.42 billion, up from $1.36 billion in fiscal 2021: a level of support that would be strong even during a capital campaign. Gifts for endowment—up 26 percent, to $584 million—were the standout category. Suggesting the strength of Harvard’s philanthropic pipeline, pledges receivable (i.e., future gift commitments) rose from $2.3 billion to $2.6 billion, with increases of more than $100 million each in pledges for current-use and endowment gifts.

The Endowment: What Goes Up…

Deflating equities. The change from near-record endowment investment returns in fiscal 2021 to losses this year requires little in the way of explanation. “The disparity…was stark and reinforces the necessity of focusing on long-term, risk-adjusted returns,” as HMC chief executive officer N.P. Narvekar put it in his succinct annual message. “By far the most significant impact,” he explained, “was the poor performance of global equity markets over the course of the year,” with the principal benchmarks for domestic and global stocks declining between 11 percent and 27 percent as inflation accelerated, central bankers raised interest rates swiftly, and the risks of recession increased.

The endowment’s value decreased from $53.2 billion at the end of fiscal 2021 to $50.9 billion as of last June 30, chiefly reflecting:

• realized and unrealized investment losses of $1.1 billion;

• the $2.1-billion distribution to support University operations; and

• the receipt of those gifts (about $0.6 billion), plus other fund transfers and increased pledge balances (Harvard counts pledges for endowment gifts in its total).

The investment carnage was essentially universal. Among peer institutions disclosing results so far, MIT had a negative 5.3 percent return in fiscal 2022 (versus positive 55.5 percent in fiscal 2021) and Yale positive 0.8 percent (positive 40.2 percent)—with Princeton and Stanford yet to weigh in. Cornell reported negative 1.3 percent (versus positive 41.9 percent), Dartmouth negative 3.1 percent (positive 46.5 percent), Duke negative 1.5 percent (positive 55.9 percent), Penn essentially breakeven results (versus 41.1 percent); and the University of Virginia negative 4.7 percent (positive 49 percent). Updated October 19, 2022, 12:50 p.m.: Stanford yesterday reported a negative 4.2 percent return on endoment investments for its fiscal year 2022. Updated October 28, 2022, 10:30 a.m.: Completing the reports of fiscal 2022 results by major universities with diversified portfolios like Harvard’s, and by academic peer institutions, Princeton today said its investment return for the year was a negative 1.5 percent (versus 46.9 pecent).

N.P. Narvekar, CEO, Harvard Management Company

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Management Company

According to the Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service, the median endowment suffered an investment return of negative 10.2 percent during the fiscal year (versus a 27 percent gain in fiscal 2021). The largest endowments, like those just listed, obviously did considerably better—for a reason that deserves the closest scrutiny. “[T]he highest-risk asset classes—i.e., the private portfolios of venture capital, buyout, and real estate—were the strongest performers,” according to Narvekar. Larger endowments invest disproportionately in these illiquid assets, so their performance was skewed, favorably, in an otherwise punishing year: “In fact, the more private assets an investor had in its portfolio in FY 22, the stronger their performance.”

Here, however, a surprising change in Harvard’s disclosures limits outsiders’ ability to understand HMC’s results. Departing from decades of practice, neither HMC separately nor the University’s annual financial report include data on the allocation of endowment assets or on performance by asset class. In fiscal 2021, for instance, HMC reported that 81 percent of assets were largely equity-linked, with public equities accounting for 14 percent of endowment holdings (and returning 50 percent for the year), private equity 34 percent (77 percent return), and hedge funds 33 percent (16 percent return).

No such information is being provided now. HMC, as reorganized by Narvekar, now comprises a small team of generalists, with funds managed almost entirely by external investment firms, and emphasizes overall, long-term returns. And some of the former reporting categories may have outlived their usefulness: “private equity” includes venture capital, buyouts, and other assets, and “hedge funds” embrace wildly diverse strategies—making the terms themselves increasingly arbitrary.

Nonetheless, HMC’s allocation decisions and return expectations and analyses still reflect different kinds of assets. From the footnotes accompanying the annual financial statements, it is possible to see the share of various categories of holdings within the University’s pooled general investment account. But because that combines endowment and other assets, the endowment allocation is not clearly observable. And performance by asset class is not a part of those data. Doing away with the old form of reporting avoids inadvertent imprecision, but replacing it with nothing more than an overall return number and ending endowment value means that the endowment as a whole appears to interested members of the Harvard community as an undifferentiated black box.

Valuing private assets: a cautionary tale. The loss of such information is particularly significant this year, given Narvekar’s observations on the performance of private assets. Critically, the valuation of such assets is something of an art—in contrast to pricing, say, a publicly held stock, where quotations from recent trades are universally available in an instant, to the penny.

As Narvekar noted, the positive valuations given private assets, at a time when public securities have depreciated sharply, “may indicate that private managers have not yet marked their portfolios to reflect general market conditions. This phenomenon does make us cautious about forward-looking returns in private portfolios.” In other words, given the widely dissimilar results for public and private equities, the relatively favorable data released today may reflect embedded future risks.

For example, venture-capital money managers typically mark the value of their investments from the most recent funding round for the young enterprises they support. A year ago, “unicorns” (startups thought to be worth at least a billion dollars) numbered in the dozens or hundreds of companies; investors were piling in, in record volume, at breathtaking valuations—and those valuations could be tested in a strong market for initial public offerings. Now, some of those firms (whose hoped-for, future profits have yet to materialize) have been revaluated downward by billions, or multiple billions, of dollars as their shares have traded, or in more recent private financing rounds. That is the inexorable result of rising interest and discount rates, and fears that recession may wreck their owners’ hopes before they in fact become successful.

As Narvekar drily put it, the method of pricing private investment holdings “may slow the process of moving existing valuations to fair value.” Accordingly, he observed, “the end of the current calendar year might present meaningful adjustments to these valuations, as investment managers audit their portfolios.” In other words, reported performance for such assets during endowments’ fiscal 2023 might be considerably less bubbly. Or, during the next few years, returns for these asset classes may well trail their strong results in the recent past, and might lag a recovery in public securities when economic and financial-market conditions improve.

“This circumstance is not unique to Harvard,” Narvekar wrote, as “other institutional investors with large private portfolios will almost certainly face the same dynamic.” Peer institutions, in fact, often weight private assets more heavily in their endowment portfolios than HMC does. But whatever their mix of holdings, across such institutions, a challenge clearly looms.

(In a bit of a victory lap, Narvekar reported, “[W]e are particularly pleased that we were able to sell close to $1 billion of private equity funds in the secondary market during the summer of 2021—a time of significant ebullience—avoiding the discounts these funds would likely face today.” As reported last year, the 77 percent investment return on private-equity assets during fiscal 2021 increased the share of such holdings in the endowment by 11 percentage points—a staggering one-year shift for an illiquid category of assets, given the size of Harvard’s portfolio. That likely provided an opportunity to dispose of some legacy holdings as HMC’s team put money to work in new investments. Since he began restructuring HMC upon his arrival in late 2016, Narvekar has not been shy about selling holdings where he saw constrained future potential—notably, in real estate, natural resources, and some categories of private equity.)

Other issues. Given the future risk embedded in the returns reported for private assets today, other aspects of HMC’s fiscal 2022 results merit further unpacking. Narvekar highlighted two.

First, although managers responsible for investing HMC’s public equities, hedge funds, and private equities produced performance that “had been unusually strong over the past four fiscal years, FY 22 was not a strong benchmark relative year.” In other words, returns reverted somewhat toward the mean, as one might expect. Narvekar reiterated the importance of focusing on longer-term performance, over five-year periods (or the longer duration of an entire economic and investment cycle, his preferred metric). Implicitly, the strong relative performance during the first years Narvekar was in charge was an unexpected, and welcome, surprise—but not something to bank on.

Second, the only investment theme that really worked this year was fossil fuels—oil, natural gas, and coal—whose prices skyrocketed once Russia invaded Ukraine and upended the European and world energy markets. Investors whose portfolios include conventional energy equities or the underlying commodities harvested the financial rewards during fiscal 2022. HMC, of course, did not, “given the University’s commitment to tackling the impacts of climate change, supporting sustainable solutions, and achieving our stated net-zero goals.”

Although his report does not detail the results further, HMC’s hedge-fund assets—at least some share of which is deliberately not correlated with public equity markets—likely helped to buffer results during the year. And the relatively smaller real-estate holdings (5 percent of assets in fiscal 2021, and perhaps more now) also did well.

Looking ahead. From here, real estate—a class that is acutely sensitive to rising interest rates—poses some of the same valuation risks that hang over other private assets. And public stock holdings in foreign markets may be adversely affected by the recent, sharp appreciation of the dollar (overseas earnings are reduced when they are translated from other currencies into more expensive greenbacks). The same factor—and international recession risks—will also weigh on the valuation of privately held companies operating abroad. So Narvekar and his colleagues have plenty to worry about, even with the fiscal 2022 results now in the rearview mirror.

One thing they no longer have to worry about, however, is the University’s appetite for investment risk. After a multiyear analysis and discussions between HMC and the University’s Finance Committee, the Corporation in November agreed to “moderately increase the risk level of the portfolio,” he reported: in other words, to weight the endowment somewhat more toward equity investments. The decision probably reflects increasing confidence that the University’s financial processes and controls have improved since the huge losses incurred in the 2008 financial crisis; enhanced liquidity and reduced costs for borrowings; the investments in campus facilities and reduction in deferred maintenance; the improved funding status for such long-term liabilities as future pension and retiree healthcare costs; the overhaul of HMC itself; and, of course, the recent operating surpluses, even during the unprecedented circumstances presented by the pandemic.

HMC will likely be selective about implementing the new guidelines. Given the recent appreciation of private equity values, and current questions about what those values actually are, the depressed public markets may prove more attractive. In any event, adjusting the level of investment risk in the portfolio will be a multiyear process, Narvekar indicated.

In Prospect

Harvard has now operated in the black since fiscal 2014, and has produced nine-digit surpluses annually since fiscal 2017. Careful control of costs following the financial crisis and Great Recession helped; so did a long period of low inflation, generally favorable investment markets, and the manifestly successful University Campaign, which raised $9.6 billion.

As noted, with the return to more normal residential, on-campus operations, the University’s financial profile resumed something like its traditional shape in fiscal 2022, with student income contributing a larger share of revenues, and distributions from the endowment a slightly smaller proportion (but still the largest share by far).

The operating surpluses have largely accrued to the schools, whose deans, as Hollister and Finnegan put it, can decide among “reinvesting into their respective missions, or setting aside funds for rainy day reserves or future programmatic expansion.” One hopes that the academic animal spirits are stirring again: as it tightened its belt, for example, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ professorial cohort declined from 728 in fiscal 2020 to 711 a year later—at a time when it, and other faculties, are seeking to grow into new areas. (Data for 2022 become available next month.) At the October 11 faculty meeting (the first held in person since February 2020), FAS dean Claudine Gay reported that she has authorized a search for three professors specializing in sustainability and climate change during the next two years: a welcome step, if a rather measured one, given the priority the University is now giving to the field.

Atop the retained surpluses, deans can look forward to continued growth in the endowment distribution, which is scheduled to increase 4.5 percent per unit in this fiscal year (nearly twice the rate authorized for fiscal 2022), plus the proceeds from new units. (The University’s funding formula would have yielded a much larger increase for this year, on the order of 9 percent per unit, based on the outsized endowment investment returns in fiscal 2021. But the Corporation put a “collar” on the distribution increase to smooth it out in line with the schools’ capacity to spend new funds sustainably, and to hedge against lower endowment returns—the latter, very wisely, as fiscal 2022 results have shown. That modified formula for distributing endowment funds may also ease the financial transition to a new president, who will succeed Lawrence S. Bacow next summer.)

And then there are expenses. After wage and salary increases of zero in fiscal 2021, 2 percent in fiscal 2022 [Corrected October 13, 2022, 4:25 p.m.: 2.5 percent], and 4 percent in the current year [Corrected October 13, 2022, 5:25 p.m.: 4 percent originally, subsequently raised to 4.5 percent], nonunion employees will want to catch up in an inflationary economy. Tuition and fees have continued to increase—typically, about 3.5 percent year for the undergraduate term bill—helping to widen the spread between revenues and expenses. But the surge in enrollment should taper off as deferred matriculation and leaves of absence revert to normal levels during the next academic year or two. Construction spending is at a moderate rate (even if costs for the work under way remain elevated). Medical costs might begin to escalate, as area hospitals, no longer supported by extraordinary pandemic relief, report losses. And with energy costs rising dramatically, that expense for building operations will certainly increase sharply this year.

Longer term, the degree to which work is conducted remotely or on a hybrid basis, and the relative share of teaching (particularly for executive and continuing education) conducted online will have a significant effect on space requirements and costs.

These are all concerns for financial managers. Hollister and Finnegan caution that accumulating reserves is “wise at this time as inflation increases our operating and capital costs, and recession fears mount. Recessions put pressure on all sources of revenues and rapidly affect donations and research grants, as well as the need for increased financial aid.” And Narvekar’s cautions about the valuation and future performance of the endowment linger in the ear, too. Based on Harvard’s past experience with recessions and inflation, they caution that “Remaining adroit and attentive is essential as… planning ahead, including building reserves, can help buffer negative impacts during times of economic uncertainty.”

Such planning and reserves helped the University weather the pandemic in enviable financial shape. But, after years of sustained surpluses, they surely have put it in a position to exhale, celebrate what has been accomplished, and get to work on the much more enjoyable tasks of “reinvesting” and “programmatic expansion” in support of the academic mission, as well.

Read the annual financial report here; a PDF is posted here. A Harvard Gazette interview with executive vice president Meredith Weenick and vice president for finance Thomas Hollister discussing the University’s finances appears. here.