How to handle a “world on fire,” in the words of Janet McCabe ’80, J.D. ’83, deputy administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), was the focus of a daylong climate change action symposium convened May 9 by Harvard’s Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability. Headlined by a “chat” between President Lawrence S. Bacow and U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry, the Harvard Climate Symposium put leaders in the world of business and finance in conversation with top U.S. government administrators, and connected environmental advocacy groups organizing legal and civic action with a labor leader. The plenary and breakout sessions, which involved more than 50 speakers and brought 565 climate and sustainability leaders to Klarman Hall on the Harvard Business School campus (with another 1,325 observing via livestream), was the signal event of “Harvard Climate Action Week,” May 8-12, which includes numerous discussions of climate change across 10 Harvard schools and centers.

McCabe described climate shifts already occurring in vivid terms: from wildfires “consuming the American West in ways that are affecting air quality and public safety, and disrupting communities” to changes in precipitation—either too little or too much—that have “farmers suffering from drought” while threatening to wash hazardous waste into rivers. “These are massive disruptions,” she pointed out, “and getting worse.”

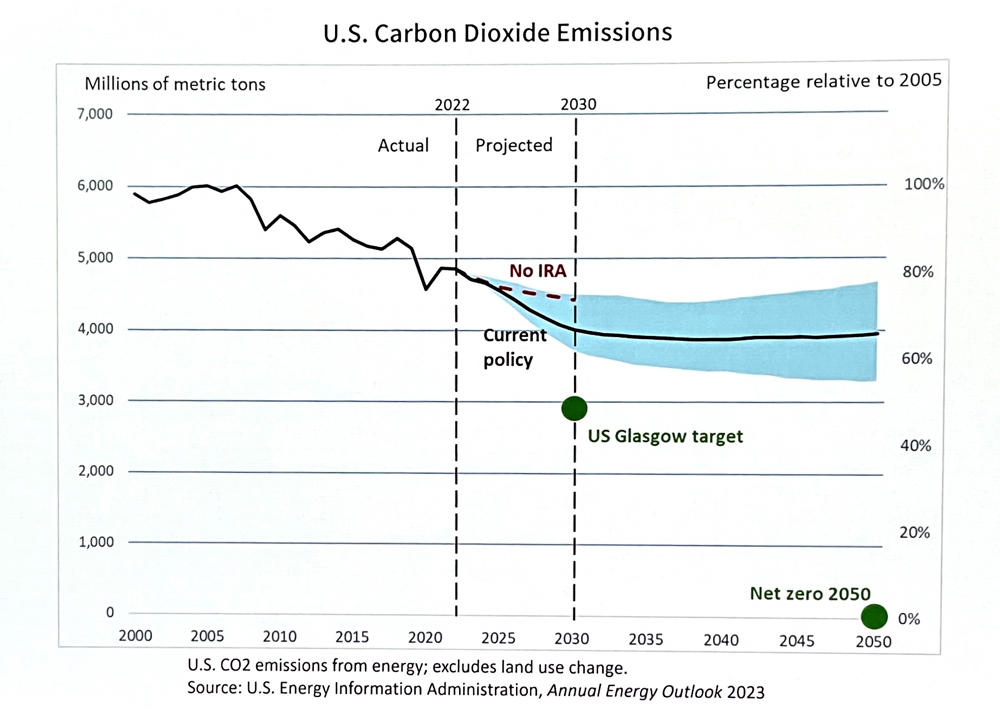

Vice provost for climate and sustainability James Stock, the Burbank professor of political economy who directs the Salata Institute, earlier framed the discussion in quantitative terms: “I’m an economist, and you’re on a university campus. So I hope you will forgive my starting the morning with a chart,” he had said, displaying a graph of projected U.S. emissions of carbon dioxide, the most important greenhouse gas by volume. The chart quantified the anticipated effect of Inflation Reduction Act, which funds programs and incentives to accelerate the transition to a clean energy economy. But it also illustrated that, unless further action is taken, the U.S. will miss the target required to keep the increase in global temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius. As Baker Foundation Professor Peter Tufano summarized the problem, “We’re on a path that is better than it could have been, but not as good as it needs to be. So, how do we move to a different, better path?”

The Inflation Reduction Act is projected to lower U.S. emissions by 2030, but not enough to hold the global average temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius

Photograph by JS/Harvard Magazine

This was the subject of the day’s ensuing discussion, which focused on government, financial and business solutions, the role of international relations, and the potential for civic action.

• Domestic policy. McCabe outlined domestic policy measures underway at the EPA. Now that the Supreme Court has ruled that carbon and hydrofluorocarbons are pollutants that affect public health and the environment, she said, the agency is moving forward with a regulatory agenda which includes proposals to control emissions of methane (a relatively short-lived gas with a greenhouse effect 20 times that of carbon dioxide) from oil and natural gas production and more aggressive energy-efficiency rules for light-, medium-, and heavy-duty vehicles “that will push this country towards a nearly zero-emission transportation fleet.” And “We are on the brink,” she added, “of putting out a proposal to address fossil-fired electricity generation.”

•Finance. Mark Carney ’87, a former central banker and member of Harvard’s Board of Overseers who chairs the Salata Institute’s advisory board, pointed out via video link from Ottawa that finance can be a catalyst when government policies, society’s values, and “the ideas and energy of entrepreneurs” are aligned. Governor of the Bank of England from 2013 to 2020, and before that, Governor of the Bank of Canada, Carney is currently chair of Brookfield Asset Management, where he heads Transition Investing. Research he conducted with U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen and others showed that when “the objectives are clear, and climate policy is increasingly credible, then what finance does is pull forward action…. It changes valuations, it moves money at large scale.” When that happens, a virtuous cycle ensues, and he believes the United States is on the cusp of such a cycle—which could help move the country closer to its emissions goals than the Inflation Reduction Act alone can effect.

He also described global progress toward climate-responsive goals in finance. Internationally, among central banks, climate-disclosure reporting is on the cusp of implementation. “There’s 120 central banks, covering 95 percent of the world’s emissions, that use their supervisory powers and stress-testing powers to make sure that banks have at least thought about what happens if we’re all serious about addressing climate change, and on the margin that helps for better management.” That’s not enough, he acknowledged. The next step, he said, is to get commitments from these banks to manage the emissions they finance in line with the 1.5 degrees Celsius target.

He added that 40 percent of the world’s private financial assets have made those commitments (see “The Endowment and the Environment: Year Three” for an account of how Harvard’s endowment is engaging this issue), representing balance sheets that they manage of more than $150 trillion. “That is enough money to finance the energy transition,” he said. “So, the money is there if we’re serious.” Now, to “pull the future forward,” he argued, what’s needed from those institutions is not just “that 2030 target [set by President Biden in 2021 to achieve a 50 to 52 percent reduction in U.S. greenhouse gas pollution from 2005 levels, as a challenge to other nations], but a five-year decarbonization plan.” Such transition plans, he reported, will soon be mandatory for all major companies in the United Kingdom.

A related effort is the creation of a net-zero data public utility that will allow anyone to see how well these institutions are performing against their targets. This will enable people to “judge who’s part of the solution, and who’s part of the problem,” he continued. “Or if, in a certain country, everybody is off target in the financial sector, perhaps it’s policy that is insufficient.” This will provide a “real-time feedback loop to policy.”

•Venture capital for innovations. Jeremy Grantham, co-founder of investment firm GMO, said that while American capitalism is “fat and happy, monopolistic, and in pretty bad shape,” the venture capital industry is the biggest, the best, and the most dynamic, attracting “wonderful people from all over the world….It interacts with the great research universities,” most of which are in America. “Without them,” he said, “most of your great ideas are not forthcoming.” His firm has therefore heavily focused its investment in green venture capital, particularly in the field of carbon sequestration, and been rewarded with class-beating annual returns on investment.

Grantham thinks that decarbonizing the global economy will cost “less than $100 trillion,” but estimates that before that job is done “we will end up with 525 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere, and we must come back to about 300. Extracting the CO2 is a bigger, more expensive proposition,” a $150-trillion problem that represents about one percent of global GDP for 90 years,” which is how long he thinks the process will require. The cost is high, but far less than the costs of unchecked climate change.

•Transitioning to a better energy system. Carney added that the fossil fuel-based energy system of the past century has “consistently proven unreliable…. It’s used as a weapon in conflict. It’s unaffordable, given the price spikes, and it’s inaccessible. There’s still a billion people in the world in energy poverty, and it’s clearly unsustainable. So, what makes anyone think that that’s the right system? What we need to do is accelerate the transition. And I think that…clearly has been the broad policy response.” Any backlash has been concentrated largely in the United States. That’s important because this country has the most important financial sector and the largest economy. This U.S. phenomenon is part of a larger political dialogue that is “only going to accelerate over the course of the next year…given the electoral cycle.”

However, Carney continued, “two-thirds of the world’s emissions are now from the emerging and developing world”—with 30 percent of that from China. Although China can finance its energy transition by and large, he said, for the rest of the world there is a lack of below-market-rate financing from development banks and multilateral funds that less affluent developing countries require to fund their energy transition.

The Special Envoy’s Worldview

John Kerry, the former secretary of state, further illuminated the problem during a conversation with Bacow on “Strengthening Global Ambition.” “Twenty nations are responsible for 76 percent of all the emissions on the planet,” he said. On “the other side of that coin, 48 nations in sub-Saharan Africa are responsible for 0.55 percent of all emissions.” The priority, he continued, lies in effecting an energy transition in a few developing countries that have larger economies: China, Russia, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, and others. “Our challenge,” he said, “is to bring them on board as fast as we can.” To that end, he continued, “We have been negotiating with a number of countries,” including South Africa, Vietnam, Indonesia, Mexico, and Brazil, where “we’re trying to put together partnerships where we can find enough concessionary funding that we can then bring the private sector to the table because we derisk the investment.” Kerry said that some $130 trillion in assets at investment companies and sovereign funds “could be directed in the appropriate direction,” if the world were prepared to make that happen.

“If we don’t do what we need to do over these 10 years and more, it is 100 percent certain,” he said, that the world the food supply will be disrupted, causing “migration pressures unlike anything” now happening at the U.S. southern border: “whole populations banging on the door, clamoring to be let in because they can’t live where they are today.”

At the same time, Kerry acknowledged that the world needs some fossil fuel in the near-term because the world “can’t transition fast enough.”

The General Motors Transition

That transition is playing out better than expected in some domestic sectors, including the automotive industry. Kristen Seimen, General Motors vice president of sustainable workplaces and chief sustainability officer, recalled that the company set a goal in 2016 to utilize only renewable energy in its operations by 2050. In 2021, GM estimated that it could achieve that goal by 2035. The following year, after a closer look, it was able to put all the agreements in place to use 100 percent renewable energy in its U.S. operations by 2025. “When we set this goal,” said Siemen, “we didn’t quite know how to get there. But the more we worked, the closer it came.”

Kristen Siemen of General Motors speaks with David Blood in a session moderated by George Serafeim.

Photograph by JS/Harvard Magazine

Still, 84 percent of the company’s carbon footprint is in customer usage, Siemen reported. “To get to zero, we have to transition to electric.” And realizing that goal may also come about faster than currently anticipated. Siemen said that even GM’s most traditional suppliers, long focused on internal combustion engines, are making the transition toward electrification within their own companies, leading to valuable innovations.

Economic Impacts and Environmental Advocacy

The final plenary session of the day was a discussion among Roxanne Brown, international vice president at large of the United Steelworkers union, and environmental advocacy organization leaders Sam Sankar, the senior vice president for programs at Earthjustice, and Brad Campbell, president of the Conservation Law Foundation.

Asked by moderator and senior lecturer in leadership, organizing, and civil society Marshall Ganz what might galvanize civil action, Campbell said that when people connect “loss of life and limb from extreme weather events” to fossil fuels, that will create a sense of urgency to hold producers accountable. Both Earthjustice and the Conservation Law Foundation engage in extensive litigation to impel changes in fossil-fuel use and climate-related policy decisions. Erosion of the fossil-fuel industry’s social license to pollute has already begun, he said, and litigation plays a major role in that. “Powerful corporations with popular products are very hard to rein in until their social license begins to decline.” But when it happens, that will “finally push the transition forward.”

Litigation in support of local communities is another dimension of this process. Campbell noted that ExxonMobil has a major oil terminal in Everett, Massachusetts, where houses in an adjacent low-income community are built right up to the fence line. “Every projection of a Category 1 storm puts that facility underwater,” said Campbell. “We’ve seen in [hurricanes] Irene and Katrina that the tanks at that facility are the type that collapse readily. And even though ExxonMobil has known for decades, doing very good science, about the risks of disaster that this this presented to this community, they’ve done nothing to prepare that facility. And we worked with the communities… to raise up [awareness of] that risk, and also brought litigation to hold the company accountable under the law for failing to prepare that facility….”

Asked by a member of the audience whether everyone is culpable—“We wanted heat, light…a salad in January in Massachusetts”—Campbell and Sankar forcefully rejected that proposition, noting that the leaders of certain industries knew the science and nevertheless deceived the public for decades. It’s not consumers who are responsible for a broken system, Campbell said, when the companies have “held their stranglehold on public policy and blocked solutions that have been on the table for 30 years.”

Brown agreed and said that many steelworkers are concerned about climate change: superstorms in the Gulf of Mexico that flood oil refineries put them out of work—for others drought dries up the streams where they fish or drives animals from the areas where they hunt. These local issues, she said, are what create urgency for her constituency.

But the phrase, “energy transition,” she said, some “describe as a fancy funeral.” “Whenever I hear the narrative about ‘We need to shift away from fossil fuels and close refineries and shut down coal-fired power plants,’” she continued, addressing in particular the students in the audience, “as you are getting ready to go out into the world, remember the humans around that narrative. It’s so easy sitting here in Cambridge to say, ‘Oh, those industries are terrible, they’re awful. They’ve lied.’ They have, but at the same time, they’ve also provided a livelihood for communities.” Her union members in the refining industry make a family-sustaining wage, $150,000 a year. The jobs in clean energy, she said, pay $60,000 a year. “We want environmental sustainability—it’s necessary. But workers deserve economic sustainability.” How to deliver a just energy transition is the question, because “We don’t need a funeral for 850,000 steelworker members. We need jobs. We need a future.”

As the symposium wound down, Sankar talked about the moment when his daughter became “awake to the reality of climate and environmental concerns. She asked me an important question. At one point, she said, ‘We’re cooked, right? None of this is gonna really work, right?’ And I said, ‘No.’ And I said exactly this, that ‘The possibilities are there, we can do this.’”

In his concluding remarks, Stock thanked the Salatas for their institute-founding gift. And he repeated Sankar’s theme: “Our job is not to think of what’s likely or what the probable is, but instead to think about the possible, and how we can affect those probabilities through our works…as individuals and as institutional leaders” so that the best possible outcomes are the ones that materialize.

•••••••

In addition to the major presentations, in-person attendees at the symposium also spent the afternoon in breakout sessions that covered a wide variety of climate-related topics, suggesting the scope of the complex issues that must be addressed to achieve a more sustainable future. They included: international security; entrepreneurship focused on carbon capture and storage; scientific research on heat stress; climate investment and accelerating the adoption of new technologies; U.S. energy infrastructure and deployment of a low-carbon electrical distribution grid; inclusion and social action in effecting solutions to climate-change problems; trade policy; financing the energy transition in less developed countries whose agrarian economies are at risk; basic climate science; and the national legislative and policymaking outlook in the United States.