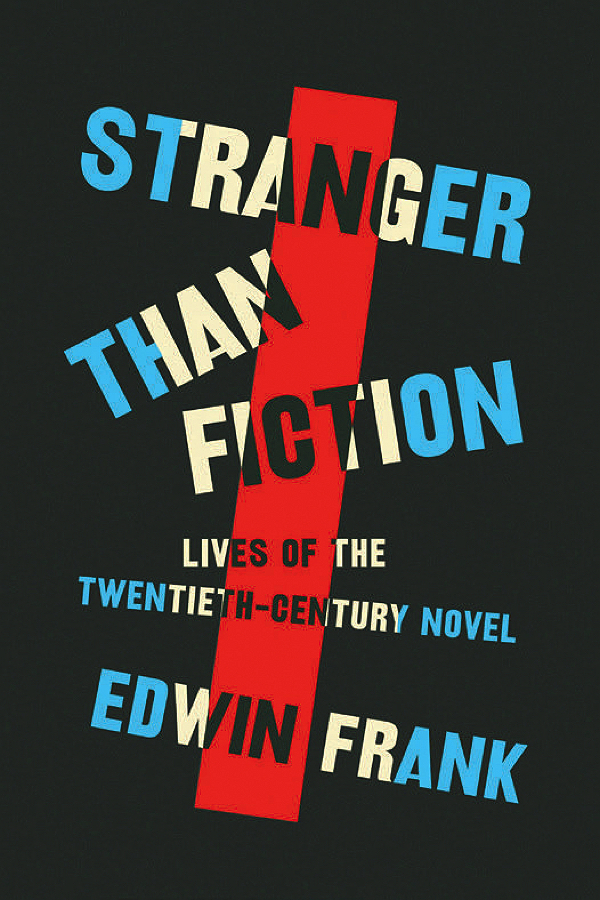

In the opening pages of his new book, Stranger Than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel, Edwin Frank ’82 tries to explain exactly what he’s up to. This turns out to be a slippery task. Stranger Than Fiction is a book about books, but it’s not a compilation, or a survey—or “God forbid,” he says, a “theory of the novel.” Instead, it’s a story. The main protagonist is the twentieth-century novel itself (“an exploding art form in an exploding world”), which he came to see as a fictional character in its own right. The narrative, set amid the near-constant upheavals of the 1900s, depicts how the novel “grew up, how it changed, how it struggled, how it grew old,” Frank says.

What emerges is a chronicle of staggering richness. Braiding together world events, literary histories, author biographies, and details of plot, theme, scene, and character, Frank spends time with celebrated works—In Search of Lost Time, Ulysses, Mrs. Dalloway, Lolita, One Hundred Years of Solitude—while also illuminating lesser-known gems like Hans Erich Nossack’s The End, Anna Banti’s Artemisia, and Alfred Kubin’s The Other Side. Altogether, he analyzes 32 novels from around the globe, with at least glancing attention to countless others, assembling not so much a canon as a “constellation.” The project took him 15 years.

It makes sense that Frank would write this book. For 25 years, he’s been publishing out-of-print titles, new translations, and obscure or overlooked texts as founder and editorial director at New York Review Books (NYRB). A division of the literary magazine The New York Review of Books (and a financially self-sustaining one, no small feat in today’s publishing climate), the NYRB publishes poetry, children’s books, and comics, as well as volumes by the magazine’s contributors. But the backbone of the enterprise is the “classics” series, a rigorously eclectic catalog that Frank sometimes compares to the vinyl section of a record store, with “that ability to rifle through the bins, where you’re browsing for what you like and educating yourself at the same time.” A number of the series’ authors find their way into Stranger Than Fiction, including H.G. Wells, Natsume Sōseki, André Gide, Thomas Mann, and Colette, as well as Austrian modernist Robert Musil, Italian and Austro-Hungarian writer Italo Svevo, and Soviet novelist and war correspondent Vasily Grossman.

Frank, who is also a published poet, was six when he learned to read. The son of two academics (his father taught philosophy; his mother English literature), he grew up in Colorado, in a house filled with books, though he remained mostly indifferent to them, he remembers, until the year his mother received a Fulbright and the family moved to Paris. There, enrolled in a French school, feeling alien and alone, separated from his native language, he fell into Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, which his grandmother, visiting from home, began reading to him one afternoon. “It was the part where they go into the mines of Moria,” the abandoned underground city of the Dwarves, Frank recalls. “I was completely spellbound.” Here was a whole world, “offering a kind of alternate reality, as engrossing as reality. I never looked back.”

A few years later, when he was 11, his father took a yearlong sabbatical in London. Becoming a regular at local bookstores and libraries, Frank began reading his way through the Penguin Modern Classics and devoured Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. He also discovered poetry, first in Voices, an anthology of modern and contemporary work (Denise Levertov and Edwin Morgan made strong impressions), and then in the Oxford Book of English Verse, a gift from his parents.

After finishing high school at 17, he took a break to travel through Mexico and Latin America, then spent several months in India with his grandparents, who spent 10 years there as medical missionaries. At the time when Frank visited, his grandfather was working as a surgeon in a town called Kolar, not far from Bangalore; the days and nights Frank spent there cobbling together a “makeshift life” blew open his sense of the world. “I’d been to countries that had very different standards of living from the United States, but India was a world unto itself,” he says. The centerpiece of his 2015 poetry collection, Snake Train, is a pungent, affecting essay about this off-kilter experience, titled “The Accident.” It ends with him reading The Aeneid in the Kolar hospital library.

Frank got into Harvard largely on the voraciousness of his reading, he believes, and the mentors he found there were numerous and consequential: poets Seamus Heaney, Robert Fitzgerald, and William Alfred; novelist Monroe Engel; and philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who taught a class on Nietzsche. After graduation, Frank won a Stegner Fellowship to Stanford’s creative writing program, then embarked on a Ph.D. in art history at Columbia, which he never finished. Instead, in his mid-thirties, a father with two young children, he took a job with The Reader’s Catalog, an annotated list of the 40,000 “best books in print,” a kind of literary Sears catalog, published by Random House. Soon he began assembling lists of out-of-print books that could be revived, and out of that grew the NYRB, which launched in 1999.

In some ways, Frank’s life, and his life’s work, have been a series of discoveries between the pages of books. When he started the project that would become Stranger Than Fiction, he spent two years just reading (and re-reading) dozens—hundreds—of books, looking for connections and threads of revelation. “It was like being back under the covers with a flashlight,” he says. One revelation turned out to be Georges Perec’s 1978 novel, Life: A User’s Manual, a sly, delightful, and deeply sad puzzle of a story about a monumental, 50-year art project that comes to nothing. Frank hadn’t read it before; when he finally picked it up, he was enraptured and surprised. The resulting chapter in Stranger Than Fiction “was written almost on the rebound from reading that book,” he says. “Just an immediate response of excitement.” In the chapter, he calls Perec’s novel “a creation that seeks to evoke creation itself.” In a different way, that was Frank’s ambition too.