Henry Hobson Richardson, A.B. 1859, the leading nineteenth-century American architect—Boston’s Trinity Church, a major role in the design of the New York State Capitol, libraries, important commercial buildings, sumptuous homes—happily left his mark on alma mater. Fortunate members of this community can walk by the Law School’s magnificent Austin Hall (1881, purpose-built for the case-study method of instruction) and the symmetrical, highly detailed brick Sever Hall (1878, still in its original classroom use) in what is now Tercentenary Theatre.

The latter, notes Thomas Hyry, Fearrington librarian of Houghton Library, is less than 100 yards from where he now works—and where resides most of a too-little-seen or -appreciated third Richardson masterwork: collections including his drawings and those of his studio (more than 5,000 in all). These were donated in 1942 but rarely displayed, given what Hyry describes as “the relatively unwieldy nature of architectural drawings” relative to Houghton’s many other smaller items: rare books, manuscripts, and diverse archival treasures.

The solution? A book, of course: Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University, gorgeously produced with a foreword by Hyry; introduction by the architect’s biographer James F. O’Gorman, Ph.D. ’66, now emeritus from Wellesley; essays on his studio and clients by Jay Wickersham, M.Arch. ’83, J.D. ’94, past professor in practice at the Graduate School of Design, and Chris Milford, architect and historian (who has lectured at the school); and a guide to the holdings by Hope Mayo, Ph.D. ’74, the library’s retired Hofer curator of printing and graphic arts.

As O’Gorman notes, Richardson told a client that he would “design anything from a cathedral to a chicken coop.” His drawings, O’Gorman continues, show how the architect’s studio “created buildings that reflected the social makeup of American post-Civil War life”: the period of rising commercial and manufacturing centers, surrounded by residential towns and rural retreats accessed by train. Importantly, he observes, Richardson “never explained his aims as a designer in writing.” Rather, the work lives as it was built—and in the preceding drawings.

Given the unabashedly Harvardian character of the enterprise, the selections from the book presented here will be parochial, but readers who care about architecture and the built environment will be richly rewarded by plunging in more thoroughly.

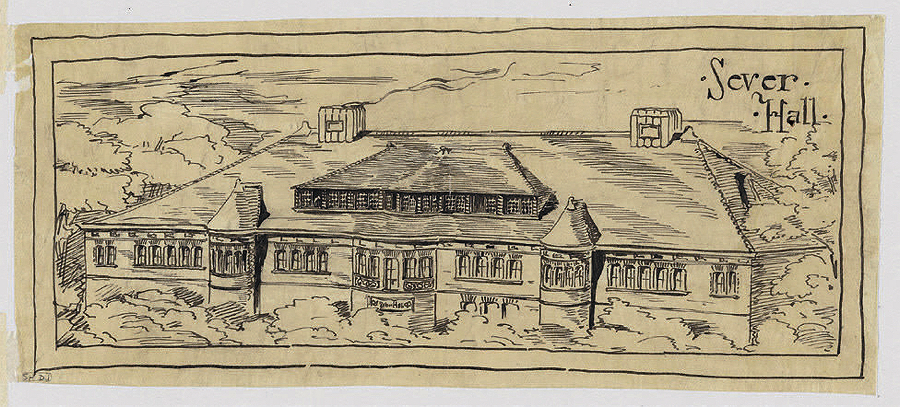

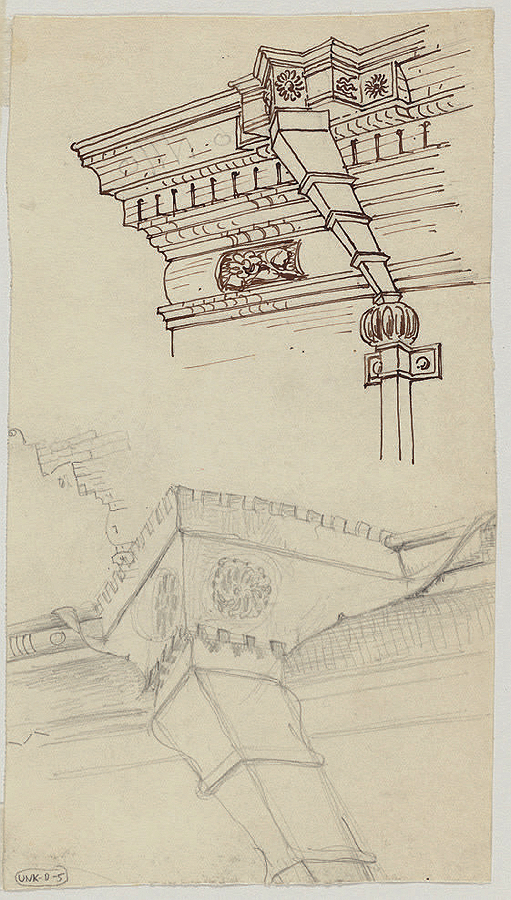

The western elevation of Sever Hall, shown in a construction drawing, exemplifies the virtue of seeing the paper plan: it is unlikely that any passersby not devoted to architectural studies can really take in the detailing, particularly in the shadow of the surrounding brick bulk of the 1900s Memorial Church and the lesser (and less distinguished) Emerson and Robinson Halls (the latter a McKim, Mead and White design), or the pedestrian Canaday dorms to the north. And those details were exceptionally finely conceived, as shown in the “studies” of downspout designs. These examples graphically demonstrate (pun acknowledged) the value of Harvard’s collections in deepening appreciation of the world beyond.

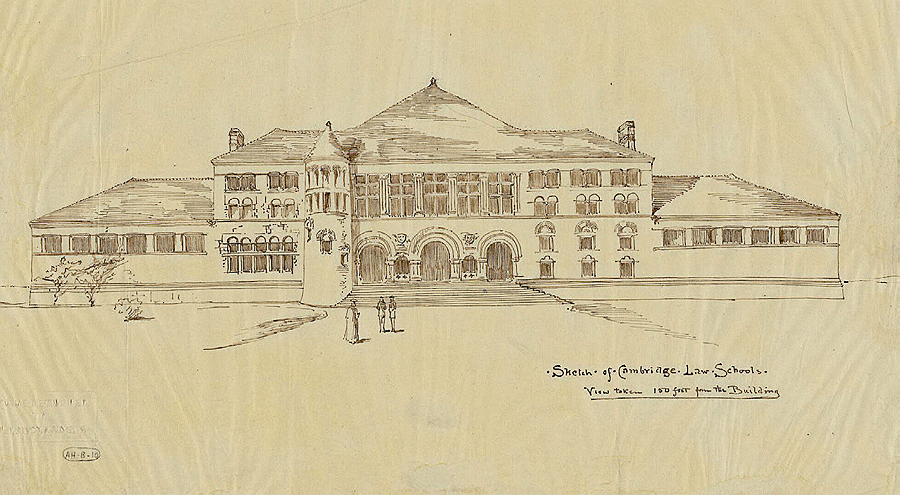

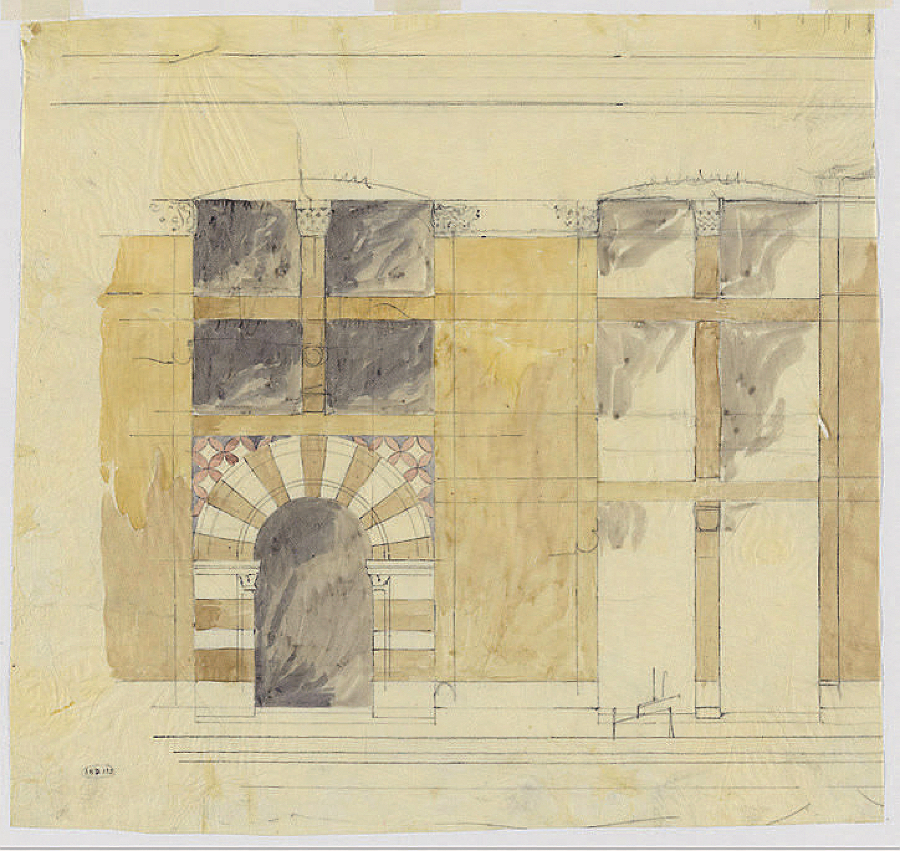

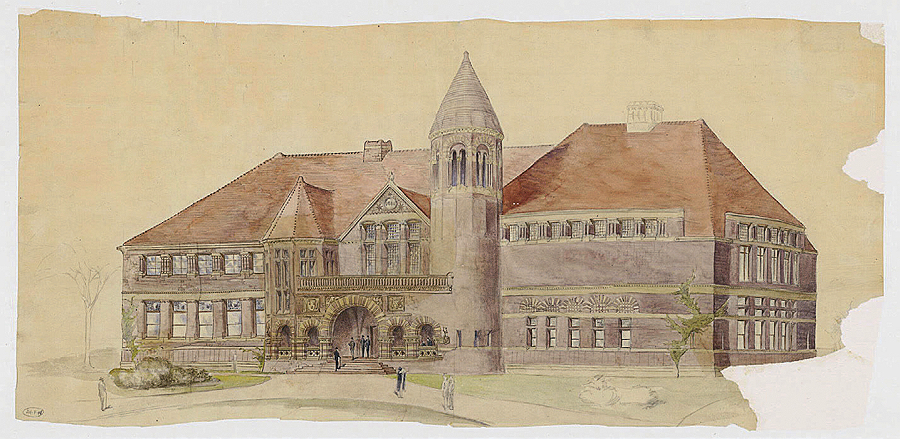

If Sever marks “Richardson’s full maturity as an architect,” as the book puts it, Austin Hall—with its great arches, polychrome stonework, and wonderful interior amphitheaters—is one of his firm’s masterpieces. Harvard’s more than 250 drawings show the evolution of two very different designs. An initial “cramped” scheme “pleased no one.” In a move that the modern University would perfect, the donor, Edwin Austin, was persuaded to up his ante, making possible the larger, T-shaped building beloved today. The perspective on the front, a presentation drawing from Harvard Law Library’s holdings, is beautiful in and of itself. A detailed design for a spandrel over the entrance arches suggests the high quality of both the draftsmanship and the subsequent construction work of the era—prerequisites to creating an enduring classic.