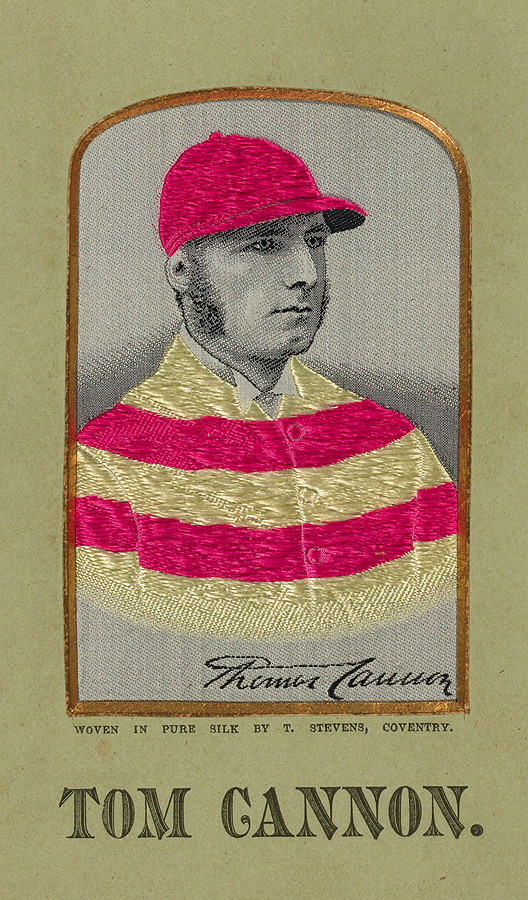

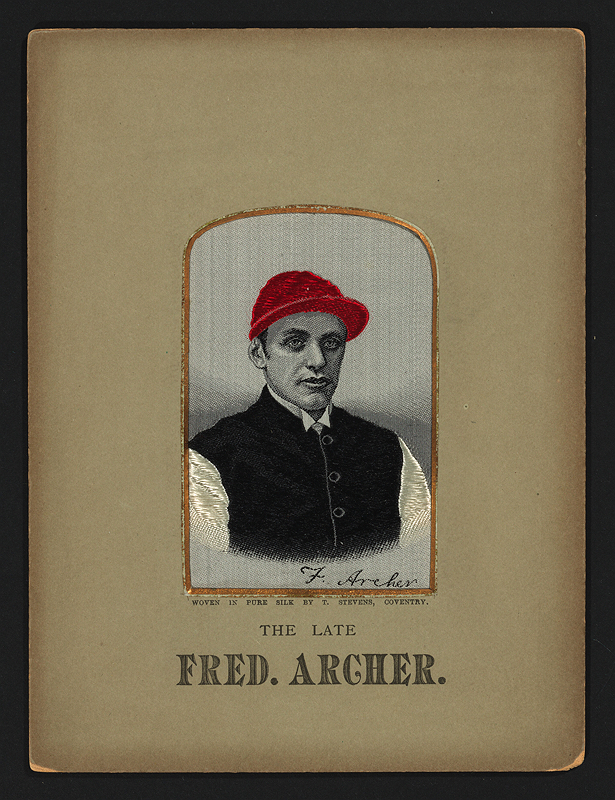

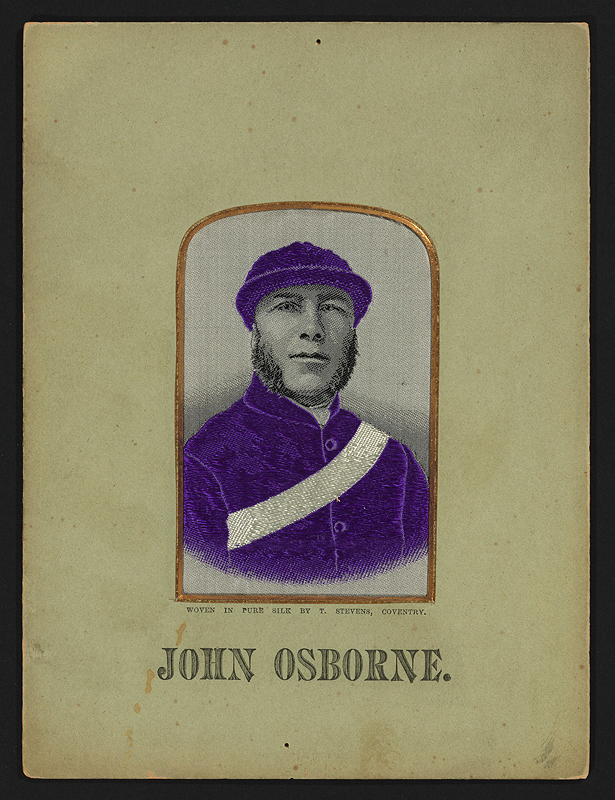

Five strange portraits stand out among the Fine Arts Library’s vast collection of historical photographs. At first, the bright colors catch the viewer’s eye. Then, the grainy quality—as if they emerged from a low-ink printer. Upon closer investigation, one realizes that the sportsmen were not photographed: they were woven.

The story of these silk portraits begins in Coventry, a city in central England. By 1860, the weaving of ribbons had dominated Coventry’s economy for 150 years. But a free-trade agreement signed between England and France that year overturned protectionist silk regulations, and soon cheap ribbons from abroad decimated Coventry’s industry.

Nonetheless, Thomas Stevens was determined to keep his business afloat. With traditional ribbon-weaving no longer profitable, he experimented with an early form of automated weaving: the Jacquard loom. Guided by a design drawn on gridded paper, a loom operator punched holes in thousands of paper cards on a machine akin to a simplified piano. Those punched cards then guided the loom, telling it what type of stitch to make in which color. Modifying existing Jacquard looms allowed Stevens to incorporate up to 10 colors and create complex photorealistic weavings dubbed “Stevengraphs.”

He began by selling woven bookmarks, which required about 5,500 punched cards to manufacture, according to a modern collectors’ association. Soon, his firm started producing greeting cards and portraits. Stevengraphs were cheaply priced “to stimulate a demand that would keep his workers in employment,” notes an account from the Coventry City Library.

Demand was indeed stimulated. In the 1870s and ’80s, Stevengraphs Works sent portable looms to trade expositions around the world. From St. Louis to Antwerp, curious onlookers could select an accent color for certain details and watch the mechanized loom weave their souvenir. Some people sent Stevengraphs as postcards. Others hung them on their walls.

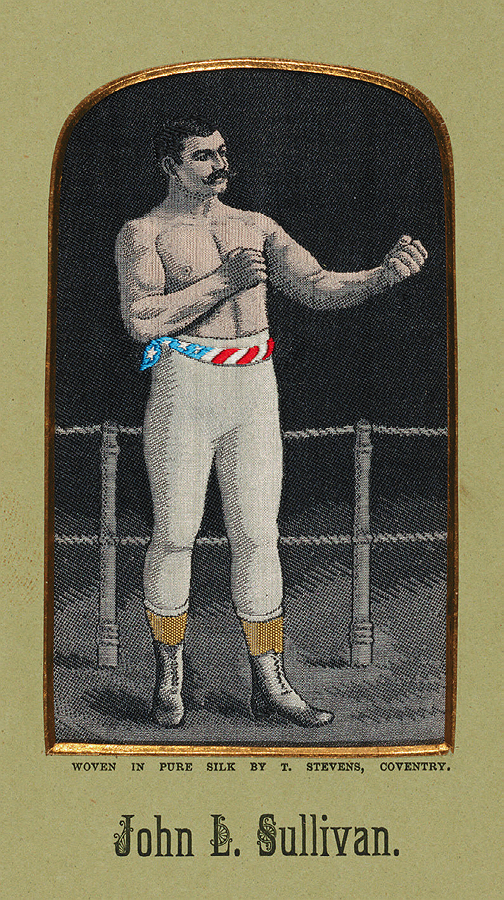

Harvard’s five Stevengraphs now reside within the Fine Arts Library’s collection of athletic portraits. Much like modern baseball cards, they feature the athlete’s likeness on the front and a career summary on the back. Instead of a mere statistical chart, though, some of these cards share legendary tales of their boxer or jockey. Owners of the John L. Sullivan card could read a nearly 1,000-word ode to the pugilist, who was “a beautiful specimen of manhood,” the collectible declared. “No man has ever been known to deal him an effective blow, and during his career he has never as much as received a discolored eye.”

When Thomas Stevens died in 1888, his son took over the firm. Consumer interest began to wane during World War I, and some of the mechanized looms were repurposed to sew labels. Harvard’s Stevengraphs were donated during this decline, notes photographic resources librarian Joanne Bloom. The manufacturer ceased operations in 1940 when its factory, like much of Coventry, was destroyed in Nazi air raids. Now, Harvard’s Stevengraphs transport viewers back 150 years. Modern students accustomed to mass-manufactured collectibles can sit in the Littauer Center and admire these portraits: drawn, punched, and woven.