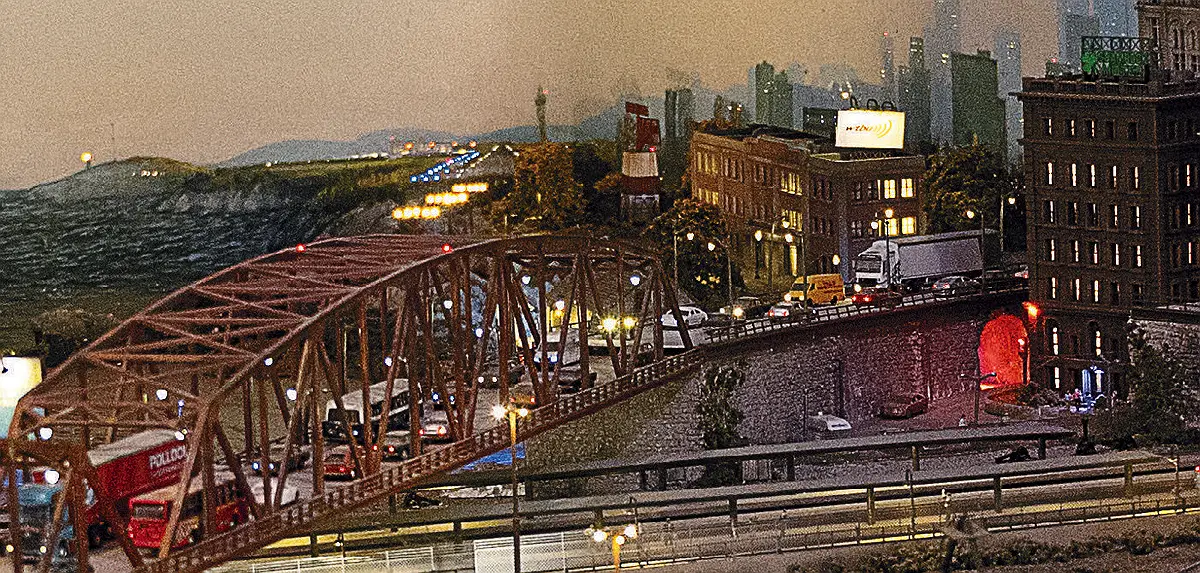

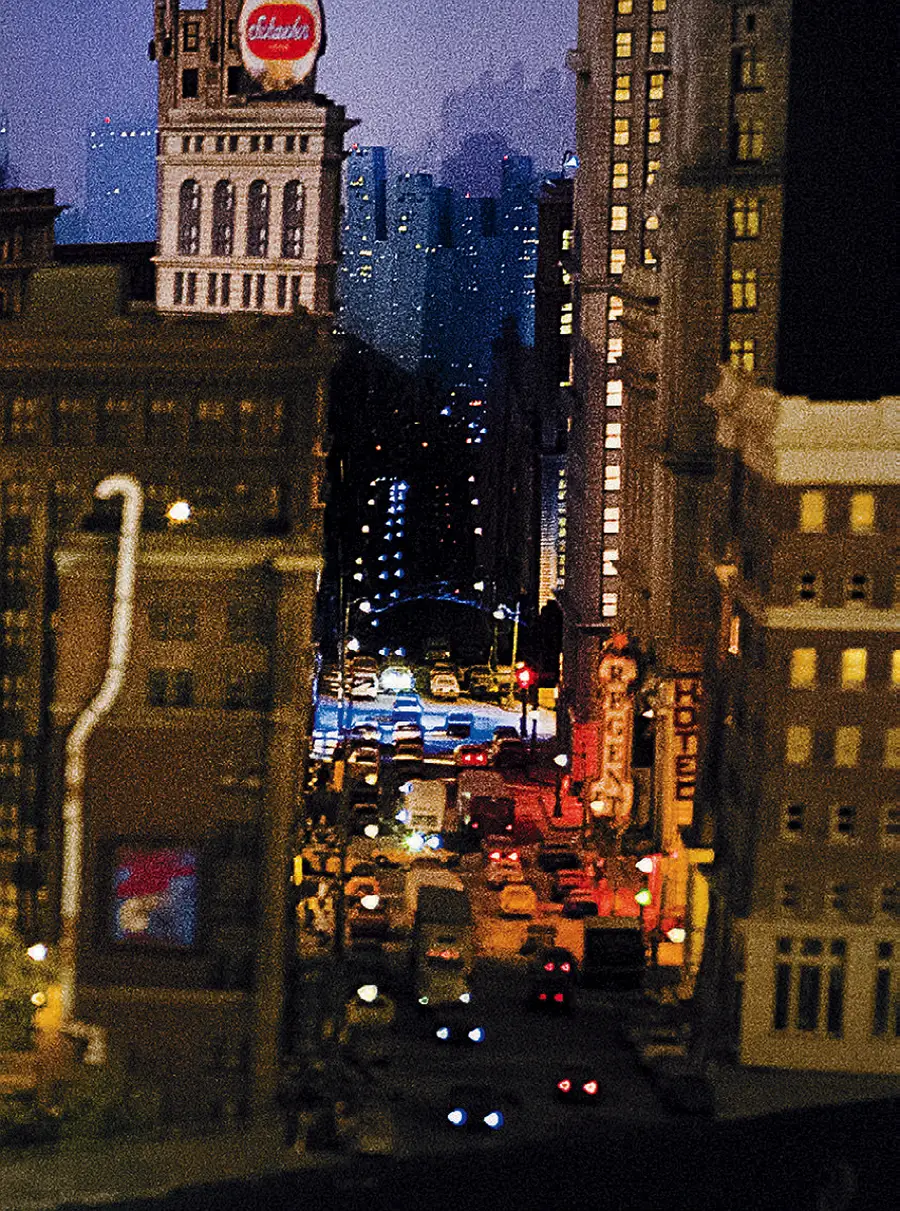

‘‘Homo sapiens tends to fall in love with miniatures,” says Fred Gevalt ’72, M.Arch. ’76. In his case, over the past eight years, in the basement of his home in Arlington, Massachusetts, Gevalt has painstakingly built a complex diorama depicting an imaginary city and neighboring rural town. Winding through it, a model railroad connects sections of the Lilliputian landscape, which measures 26 feet long and two to three feet across.

But this isn’t just another model railroad: it’s the product of a craftsman who once practiced at The Architects Collaborative (TAC), the iconic modernist firm that included Bauhaus pioneer Walter Gropius among its founders. (Gropius also chaired the architecture department at the Graduate School of Design [GSD].) Gevalt’s model renders neighborhoods and buildings with astonishing detail and verisimilitude, even though its human figures stand but half an inch tall.

He christened his miniature city “Port Charles,” and the nearby town “Maxwell Falls,” after two of his wife Gretchen’s grandsons. Port Charles includes a theater district, a “Memorial Park” complete with monuments, and a railroad terminal modeled on Philadelphia’s stately 30th Street Station. An overpass above the railroad tracks shades a shelter for the homeless, showing a notable element of urban life. Not far off, a high-rise residential area overlooks the town’s fish pier. On one side of the harbor, there’s an oil refinery and shipping docks; on the other, an airport.

An industrial zone containing that refinery, a quarry, a rock crusher, and a cement plant separates Port Charles from Maxwell Falls. A low hill juts out to face a large mountain, forming a topographical “bowl” around the small town, which includes a railroad depot, a hotel, retail stores, restaurants, a bar, a drugstore, a gym, and a small manufacturing plant. In the mountain’s shadow lies the town cemetery, containing headstones, nineteenth-century crypts, and family memorial markers, “much like what you would find in most Vermont and New Hampshire towns,” Gevalt says.

There was no preconceived plan for the layout, he explains. “I had a space and a workshop in my basement. The railroad went in first; I hired a technical consultant to make it work.” Then he began work on the surrounding world: “I had a curved backdrop I could paint to replicate the coastline, mountains, and sky as needed.” He studied dioramas in New York’s American Museum of Natural History and at the Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts (see “The Lazarus Forest,” May-June 2023, page 72). “A diorama is an explanatory tale,” he says. “It’s also a piece of art”—one that unites two- and three-dimensional elements.

He started by playing with Styrofoam to block out structures, then molded some in plaster of Paris. More buildings arose from “kit bashing,” a hobbyist term for repurposing pieces of kits to build one’s own designs. Specialists in 3-D printing offered miniature cranes, bridges, or smokestacks. The Winged Victory statue in his “Veterans Memorial Park” was cast in bronze. The enormous worldwide modeling community supports experts in every imaginable niche; a vendor in England sold Gevalt tiny stained-glass transparencies for the Maxwell Falls church. He used fiber-optic threads and backlit Plexiglass panels to produce the effects of moon, stars, aircraft, and distant cityscape and maritime lighting. Literally thousands of lights can simulate anything from noontime sun to the starry black sky of midnight.

Still, the most valuable resource might be Gevalt’s years at the GSD. After growing up in northwestern Connecticut and failing out of the University of Pennsylvania, he enlisted in the U.S. Army. As a second lieutenant trained by the Army Corps of Engineers, he deployed to Vietnam in 1967 and spent a year building roads and bridges and pulling landmines out of roads.

Afterward, he applied to Harvard “on a dare,” he says, and earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts while spending many weekends building a wooden airplane in a family garage in Connecticut. He subsequently spent hours looking down from his aircraft on steeples and smokestacks like those he would later miniaturize.

At the GSD, students built models, from corkboard and basswood, of proposed structures for coursework; they could also earn money by constructing them for local architects and developers who needed last-minute help for presentations. (This could mean three consecutive all-nighters, with an hour of sleep per night.) “Early on,” Gevalt recalls, “I learned how to build a really detailed model.”

After several years as an architect, during which he found himself traveling often for work, he decided to change careers, and in 1983 began publishing the biannual Air Charter Guide, a reference for those traveling outside the scheduled-airline sphere. He sold the publication in 2006 and did “painting, lots of sailing, and lots of flying”—including in the fighter jet he bought. But wanting to feel more productive, he began to think of returning to architecture and the models he had once loved making. He quickly learned that “nobody does it now the way we did it. Designs were being sent over the Internet to builders all over the world, who put them into 3-D printing. It was a way of operating I didn’t know anything about.”

An old college friend eventually crystallized his modeling quest. “Why do you need clients?” Russell MacAusland ’70 asked. “Why not just build models for your own pleasure? Hell, you could start with a model railroad!”

It clicked, and Gevalt was off and running. Since then, he estimates he’s spent 4,000 to 6,000 hours and an amount of money he’d “rather not think about” on the project. His diorama has become such a personal creation, and so tailored to its home habitat, that it cannot be moved anywhere else, he says. And it was the ideal hobby for a pandemic. “I didn’t need anyone else, and didn’t even need to go out!” he explains. On top of that, “I built the only COVID-free city in the world!”

Furthermore, even as the world has shifted, this art form remains valuable, albeit rarer now: beautifully rendered models still help create life-size buildings. “Larger architectural practices are not producing models nearly as much as they used to,” says associate professor in the practice of architecture Elizabeth Whittaker, founder and principal of Merge Architects in Boston. “But in academic studio courses, we consistently use models as a design tool. Models are magical. They are a fantasy of what a building or place could be.”