Near the woods behind Justin Peyser’s Long Island home sits a sculpture he built from cedar planks and giant metal rings. Titled Sanctuary, the work is massive, almost like an open-air room, or a stand of trees. It invites visitors to step inside, but once they do, the way out again becomes suddenly less clear, beset by obstacles and impediments that weren’t visible before. On closer inspection, the metal rings, hammered into the wood at different heights, look imposing and perhaps a little dangerous. “You don’t want to hit your body on those things,” Peyser says. Some of them resemble shackles; others are actually hooks.

When Peyser ’86 designed the sculpture, he’d recently returned from living in Italy with his family, and he was reading and thinking a lot about sanctuary and asylum—both the medieval tradition of fugitives claiming refuge in churches and the modern spectacle of asylum-seekers making perilous boat journeys from Africa and the Middle East to try to reach European shores. “I didn’t want to convey complete security and safety in the end,” he says, “because, oftentimes in history, sanctuary was temporary and then you were kicked out, or your fate was negotiated for you. Sometimes you didn’t make it.” For people crossing the Mediterranean today, that’s still true.

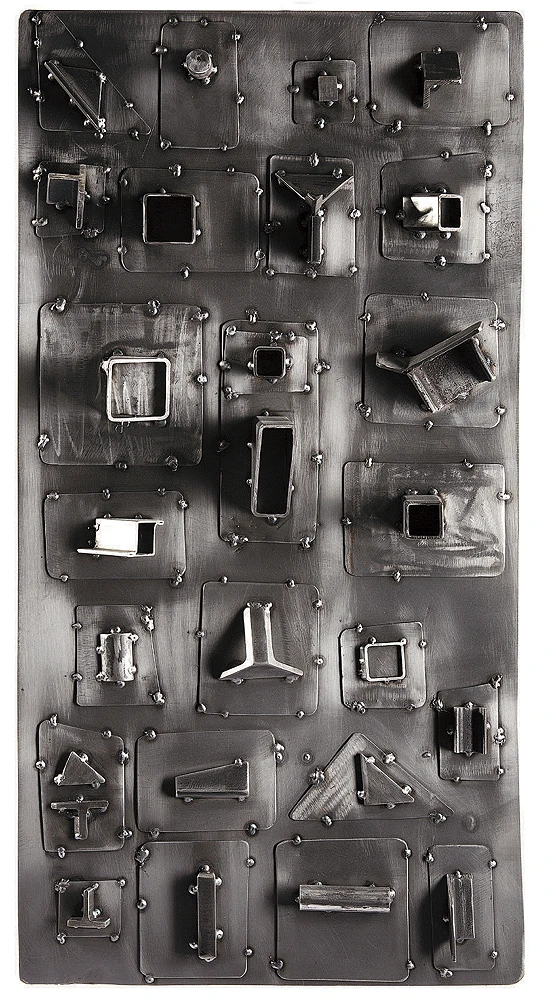

Peyser finished Sanctuary in 2023, and since then he’s found himself returning often to its themes. He’s working on a series of smaller, related pieces: abstract poster-sized “floor plans” and “maps” of the original sculpture, welding metal squares, some wrinkled and corroded, onto a flat surface, or stitching them together loosely with copper wire. There’s a faraway, fragile quality to these pieces. “It’s as if they’re being seen from the sky,” he says. The perspective is similar in another series, Territories, constructed like a collection of landscapes—or cityscapes—in relief, with metal blocks of different sizes and shapes affixed to steel plates in tidy rows, like buildings. Two of the works incorporate bare branches that tower over the other elements; in one, the entire landscape sits atop a metal table.

The longer one stares at these sculptures, though, the more something feels off: the angles or the scale don’t quite add up; the contrasts are confusing. “The word ‘territory’ is not neutral at all,” Peyser says. “It implies a sense of ownership, or at least control. That can manifest in transcendent ways, and also in ways that are rather pernicious, whether that’s displacement, migration, gentrification, violence.”

For Peyser, these obsessions run deep. Art is his second career—he spent 20 years in housing and community development—but the seeds of his artwork were planted in childhood. He and his siblings grew up in a suburb of Newark, New Jersey, during the 1960s and ’70s. Their father was a physician at a hospital in the city, and their mother a Broadway producer. On weekends, the family would take cultural trips into New York City: “We were brought to every possible museum, every possible opera,” he recalls. Each time, they’d drive past Newark, in those days a desiccated and impoverished place, hollowed out by years of white flight and deindustrialization. The 1967 riots, which accelerated Newark’s decline, occurred three years after Peyser was born. “And I always had questions like, what happened here?” he remembers. “What happened to this city?” Both his parents had grown up in Newark when it was still thriving. Decades later, “The devastation and abandonment and transience, the American comfort with obsolescence—in a certain way, all that was mystifying to me,” he says. “Those questions stayed inside me.”

Peyser arrived at Harvard intending to become a doctor like his father. Almost immediately, that plan unraveled. As a freshman he stumbled into the classroom of Orchard professor in the history of landscape John Stilgoe, whose hallmark course “Studies of the Built North American Environment since 1580” sparked interests in architecture and art—and reanimated Peyser’s still-unanswered questions about Newark’s collapse. During the next four years he studied with other artistic luminaries: painter Paul Rotterdam, sculptor Dimitri Hadzi, art historian Joseph Masheck, and architectural historian Eduard Sekler.

He graduated with a concentration in visual and environmental studies, and afterward moved to New York, where he worked first in real estate development and later spent 11 years at the Community Preservation Corporation, a nonprofit lender for affordable housing. Peyser always figured he’d return to school to become an architect, but instead he enrolled in painting classes and then a welding class, and in the mid 2000s he turned to sculpture full time. He’s since had numerous exhibitions and public-art commissions in the United States and Italy, where he’s lived on and off since his late twenties (Peyser’s wife, Michelle, is a medievalist and archaeologist from Rome; the couple have two daughters).

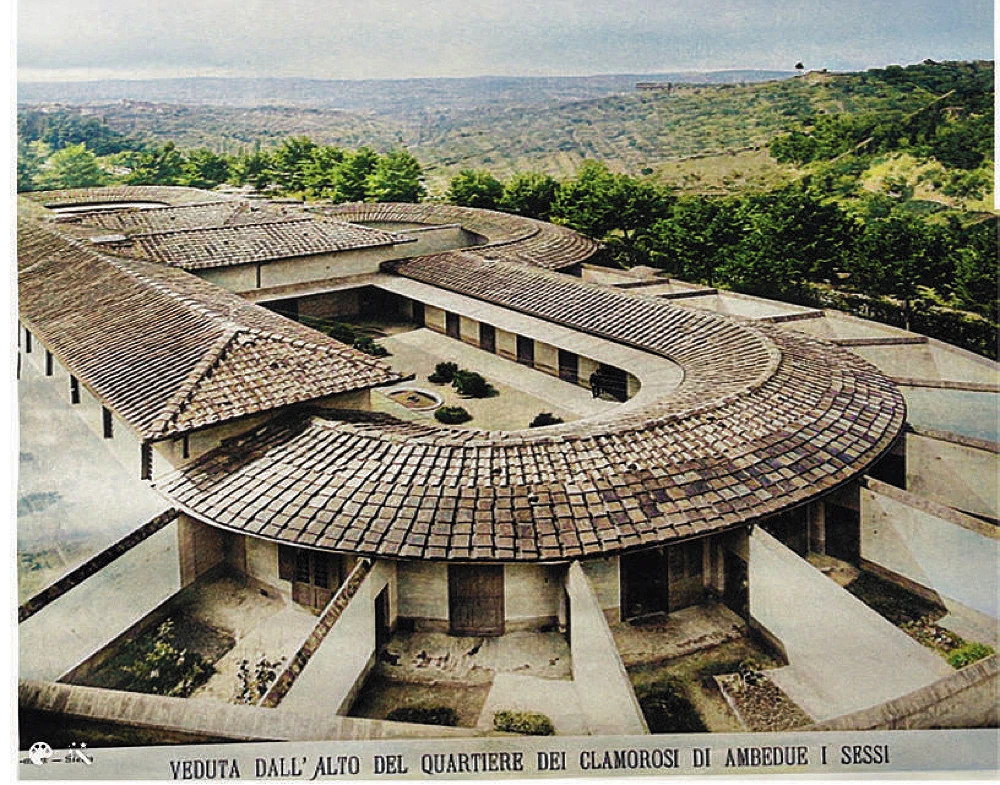

Lately, Peyser turned to a new project that ties together many of his interests—sculpture, architecture, sanctuary, territory, obsolescence, community development. He’s part of a team helping to restore the Conolly Pavilion, a nineteenth-century mental hospital near Siena, Italy. The building is a panopticon: the cells—each with its own separate walled garden—are clustered in a circle along a central column, from which a single guard could monitor all the patients (built for surveillance, most panopticons were prisons). The hospital, which once treated some of the most serious mental illnesses, closed in 1999 and for 20 years has stood empty. “It’s a gorgeous building,” Peyser says, “but it needs a lot of work to save it.”

The city’s proposed plans for the panopticon and a few neighboring structures include a hostel and bicycle hotel, visitor center, cafeteria, and museum. The team also wants to have artists create site-specific works for the patients’ cells, to “ennoble and enlighten,” Peyser says, the building’s “harsh” history. “It’s a project with a high degree of difficulty,” he says. “There are a lot of potential pitfalls.” But given the chance to revive a forgotten and abandoned place, to recover its beauty and meaning, he says, “That’s everything.”