“Where else but Harvard would you find, in one room, the grandson of Matisse, the grandson of Joyce, and the great-great-grandson of God?” John Finley’s offhand remark about an Eliot House suite to a New York Times reporter captured the magic of the House during his mastership. What it failed to capture was the man responsible for it: Finley himself.

Finley’s students knew he regarded Twain’s Huck Finn as America’s Odysseus. Fewer knew that Twain was a friend of Finley’s family. Or that e.e. cummings wrote a poem about him, Archibald MacLeish basically was his replacement during Finley’s year at Oxford, and Robert Frost dedicated a poem to him (by mistake) at John F. Kennedy’s inauguration.

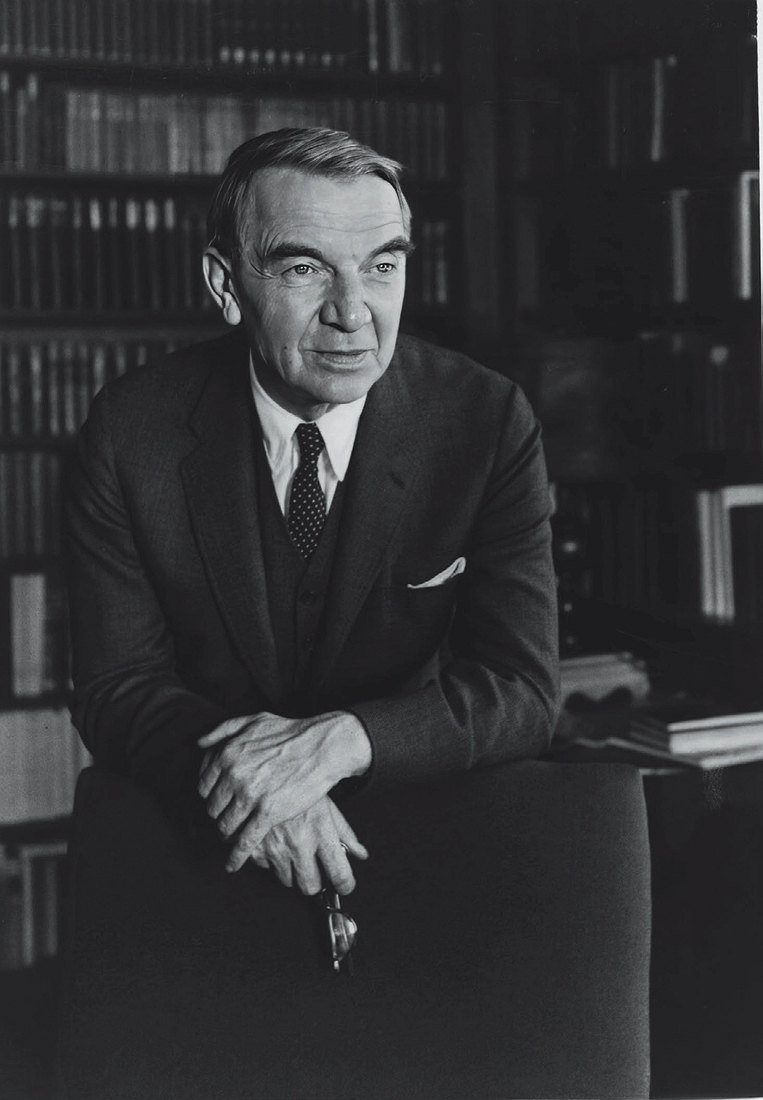

Long before John Finley ’25, Ph.D. ’33, L.H.D. ’68, was Master Finley, lectured on humanities in Sanders Theatre, or was recognized as one of the greatest after-dinner speakers of his day, there were hints of who Finley might become.

As a child in Tamworth, New Hampshire, he would drape a sheet over his mother and ask her to stand on a tree stump. He and his lifelong friend Francis Grover Cleveland would then give impromptu speeches at the unveiling of the “statue.” Creative? Certainly. But they were merely imitating their parents. Finley’s father was a special envoy for President Woodrow Wilson during World War I before becoming an editor of The New York Times and a founding member of the Council on Foreign Relations. Cleveland’s father was a former president of the United States.

Finley entered Harvard in 1921, where his class included Mason Hammond ’25, LL.D. ’94 (who would achieve enduring fame as a Monuments Man), and the physicist Robert Oppenheimer ’26, S.D. ’47. In the spring of Finley’s freshman year, he met the woman who would become his wife. In lieu of college, Magdalena Greenslet joined her publisher father on trips, attending salons with Gertrude Stein, dancing with Isadora Duncan, and painting with Picasso.

After college, Finley spent several years as a young Huck Finn, wandering Europe. He studied (a bit) in Athens, Berlin, and Paris, and published the book-length poem Thalia, or A Country Day. He wanted to become a poet then but received an invitation to teach at Harvard, where he taught briefly before deciding he needed to earn his Ph.D. to do it properly. The commencement of his teaching and graduate studies at Harvard effectively ended his wanderjahre, returning him to a campus transformed by Edward Harkness’s gift of the River Houses.

President James Bryant Conant named Finley the master of Eliot House in 1942. Finley would try to resign in order to enlist (Conant refused) and was later asked to serve as second among equals on the Committee on General Education. That effort reshaped education not just at Harvard but across the United States. Humanities students needed scientific exposure, the committee determined, while “technologists” needed a humanistic and moral grounding. These ideas were particularly resonant given Conant and Oppenheimer’s involvement in the development and deployment of the atomic bomb. With General Education in a Free Society (1945), Finley and the committee also sought to inoculate students against the rise of authoritarianism. The ideas remain resonant today.

The book also gave rise to the Gen Ed classes for which Finley would become known as a charismatic lecturer, beloved for his ability in “Humanities 2” and “Humanities 103” to connect the classics to the lives of his students.

Passed over for the presidency in 1953, Finley made Eliot House a microcosm of his vision for Harvard. As a deft sort of social engineer, he selected, paired, and nurtured the students who lived in Eliot, many of whom would become defining figures of the twentieth century.

A roll call of these residents would be improbable if it were in a work of fiction. Frank O’Hara ’50 and Edward Gorey ’50 were famed for their parties. O’Hara and John Ashbery ’49, Litt.D. ’01, played former resident Leonard Bernstein’s ’39, D.Mus. ’67, piano in the music room of the tower. Several founding members of The Paris Review, including Donald Hall ’51 and George Plimpton ’48, met at Eliot. At the spring formals, performers included Ella Fitzgerald and Tom Lehrer ’47, A.M. ’47 (not together). In the dining hall, one might find T.S. Eliot ’10, A.M. ’11, Litt.D. ’47, William S. Burroughs ’36, and Malcolm X (also not together). One resident, Theodore Kaczynski ’62, was described as “the most intellectual of America’s serial killers.” And another, the poet Gregory Corso, wasn’t even enrolled at Harvard but lived in a makeshift tent in the living room of Bobby Sedgwick’s ’55 suite.

Residents of Eliot and students in his classes remember Finley’s insightful career advice and his preternaturally effective letters of recommendation (which he described, collectively, as “an unfinished American novel”), which he hoped would provide “a running start for future hills.” It’s no wonder that, for many, he helped to define the Harvard experience.

“During the years of student unrest in the late 1960s and early 70s, when students were complaining about the lack of relevance of their courses and their failure to deal with the big issues of the day,” said Derek Bok, “by far the largest enrollment in any undergraduate course was in Finley’s course on ancient Athens. I attributed this to his qualities as a teacher and his ability to bring forth the timeless lessons and insights that can be perceived through the study of a human society 2,500 years ago.”