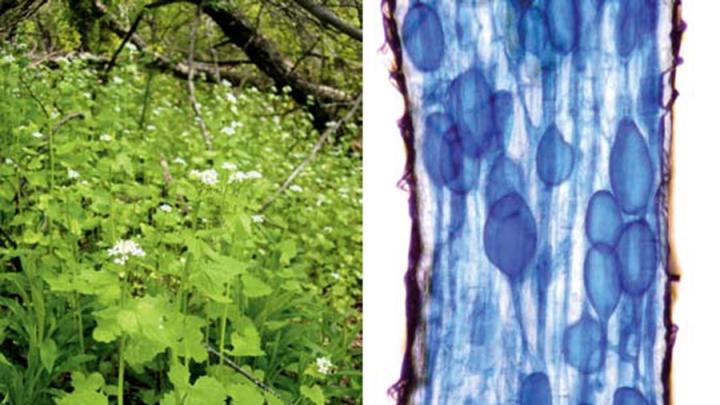

Garlic mustard, Alliaria petiolata, a European native, immigrated to the United States in the 1800s, says Kristina Stinson, “perhaps accidentally with animal feed.” Other sources (viz., the on-line Invasive Plant Atlas of New England) suggest that settlers planted it for food and medicinal purposes. Stinson allows that it is “potentially edible” and directs culinary explorers to the Internet for garlic-mustard pesto recipes. She is kind enough to say that the plant is “sweet-looking, with cute white flowers,” but notes that it isn’t as attractive, for instance, as the trilliums that it has elbowed aside in its aggressive and menacing march through forests across much of the United States and Canada. Garlic mustard is a thug.

Most non-native invasive plants establish themselves in disturbed soilbeside railroad tracks, for instance. Garlic mustard does that, but it also has demonstrated an unusual capacity to proliferate within intact North American forests. There, under the canopy of mature native hardwood trees, it outcompetes with their seedlings, such as those of sugar maples, red maples, and white ashes. Through an indirect mechanism, garlic mustard threatens infant successor trees, and if that process continues, the weed could change the composition of North American forests.

Stinson, a research associate at the Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts, is lead author of “Invasive Plant Suppresses the Growth of Native Tree Seedlings by Disrupting Belowground Mutualisms,” in Public Library of Science Biology (www.plosbiology.org). Most plants (but not garlic mustard) form symbiotic relationships with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the soil, and many depend on this association for their survival. Thus, microscopic fungi will become part of the feeding roots of a sugar maple, for example, effectively enlarging the tree’s root system and promoting growth. The fungi pass nutrients from the soil to the tree and get carbon in return.

Stinson and colleaguesworking in Petersham, Ontario, Montana, Indiana, and Germanyperformed a series of greenhouse experiments that for the first time confirmed what had only been hypothesized: garlic mustard, probably by releasing poisonous antifungal chemicals, interferes with the formation of these symbiotic relationships and reduces native plant performance. It is a disruptive presence in the forest, where fungi and tree roots, left alone, get cozy.