* * * *

As a bastion of European culture and of the privileged class that led the pro-war movement, Harvard was far closer to the fighting in Europe than was the rest of America. “At the western university where I was teaching when the war broke out in Europe,” historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote later, “it seemed to the average student as unreal as the Wars of the Roses; returning to Harvard early in 1915, one was on the outskirts of battle.”

Seventy-five years ago this November the war was winding down. On the fields of Flanders, in the forest of Argonne, and among the Italian Alps, millions of soldiers had been fighting and dying for an uncertain cause. When, in June 1917, the first American troops landed in France, the Great War became the World War. For the first time in history—but not the last—human conflict revealed its potential to reach global scale. It would be less than a quarter-century before the World War would become the First World War, and the bloodshed at the Somme, Verdun, and Ypres would be overshadowed by other horrors with other names.

Today few traces of World War I remain distinct in our collective memory: some lines from songs, the silhouette of a dough-boy, a novel, a poem, the mental image of a trench. But the war is still quite alive in the lives we lead today, for in a certain sense it was the beginning of the modern world. “We had spent our boyhoods,” John Dos Passos ’16 wrote of his generation, “in the afterglow of the peaceful nineteenth century.” The world the war made was neither peaceful nor glowing: weary, battered, cynical, imbued with bitter irony, it was the world the rest of the twentieth century inherited. Whether we imagine ourselves still possessed by that legacy, or whether we have passed, or are passing, into something new and more hopeful, it’s important to take a look back to where it began.

The generation that fought the war is dwindling. But although time has nearly succeeded where the tank and machine-guns failed, there are a few men and women left who came of age during the terrible years of 1914 to 1918. Those whose recollections follow are all Harvard and Radcliffe graduates of that time. Some of them saw the fighting firsthand, some did not, but all were affected by it. The memories and reflections that follow, collected in recent interviews, are individual histories of that time, pictures both large and small.

DULCE ET DECORUM EST . ..

Son of a prominent Boston industrialist and aviation pioneer, Thomas D. Cabot ’19, LL.D. ’70, grew up as a member of the old New England Elite, a group whose cultural traditions put it in the vanguard of the pro-intervention movement after Germany invaded Belgium in 1914. Cabot left the College after his sophomore year to enlist as an aviator: Aged 96, he is retired from a long career as a manufacturer and Harvard fundraiser.

Thomas D. Cabot. The portrait of him in uniform was painted by F.W. Benson in 1917.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

My family was a jingoist family, and I tended to be jingoist myself. I grew up with the teaching dulce et decorum est pro patria mori [“it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”]—my father always used to say that over and over again. He was very much in favor of the Allies, and in 1914 he actually bought an airplane expecting that we were going to get into the war and wanting to have us prepared. Of course, it turned out to be a hopeless airplane from the standpoint of military use; it ended up being used to patrol Boston Harbor and Massachusetts Bay during the war. It was kind of a joke, really, because the plane would take about ten hours of mechanical work for every hour it had in the air.

Most of our patriotism in College was based on two previous great wars: the American Revolution and the Civil War, the War Between the States. I was growing up only forty years after the end of the Civil War, when the memory of it was still very fresh. Many, many of my relations were killed in the Civil War. After all, it was the most sanguinary war we’ve ever had in the United States—the number of casualties, particularly among the upper class, was enormous. All of my great uncles went off to war, and many of them got killed. It left a very strong feeling of patriotism among my friends and family.

We got involved in World War I because we all had respect for our antecedents in England. But today I feel the cost of that war was much greater than the profit on it. Afterward I asked myself what we’d really gained from it.

Americans whose family backgrounds made them sympathetic to the German cause often faced suspicion or outright discrimination. Mrs. Dan H. Fenn ’20 was born in Germany and had cousins in the German army. Now 94, she lives in Cambridge, just a few blocks from the Radcliffe Quad.

Anna Fenn. The Kennedy rocker was given to her by her son Dan, who served in the Kennedy administration.

“The war hysteria started almost immediately. When I was a freshman at Radcliffe, I had to do a long theme in English A, and I chose to write a justification of Germany’s invasion of Belgium. I didn’t have any trouble with that at the time, but it turned out there was more trouble than I knew. Shortly afterward I was invited to a house party on Cape Cod. A group of us went to stay at the house of one of our classmates, and we went on a wonderful walk among the sand dunes. I liked to sketch, and I had a little sketch book with me. We came upon a strange-looking building in a hollow, and I said, “That looks interesting—I’ll draw it.” I didn’t think anything of it at all.

A few months later I was sitting in the Radcliffe Quad—there was a bench beneath a tree where we used to meet—with a girl who had been at the house party. She said, “I want to ask you something, but I want you to promise never to tell anybody what I am asking you.” Stupidly, I agreed–she was one of my best friends. She asked, “What were you doing that day when you drew that building on the Cape?” I told her I’d just been sketching. Well, it turned out that the building I’d sketched was an airplane hangar, and apparently there had been quite a subterranean excitement about that, because my friends thought that I was possibly a spy. From then on I decided that my sympathies were on the Allied side.

Eager to “see the show”—as John Dos Passos ’16 later phrased it—dozens of Harvard students got over to the front early by enlisting as “gentlemen volunteers” in one of the privately organized ambulance units that aided the French and Italian armies. In fact, of the thousand or so ambulance drivers who served in the war, 325 were Harvard students or alumni. One of them was Jerome Preston ’19, who joined the American Ambulance Field Service. Now 95, he lives in Needham, Massachusetts.

I enlisted on my eighteenth birthday, in December 1916, and went over early in February 1917 on the good ship Chicago, Compagnie Générale Transatlantique. In the wave that came over at the beginning of ’17, there were groups of college boys ranging in age from eighteen to twenty, from all over the country.

There were some from the West Coast and some from the Middle West and many from the East, of course. But they were all really the same crowd–they’d come east to school, to Williams, or Yale, or other eastern schools. This was exactly the same kind of composition as my class. When the American army began coming in at the end of ’17 and the beginning of ’18, they made quite a different appearance–they were a cross-section of America.

We arrived at the front on April sixth, the day the United States declared war. Of course, none of us ever expected to be killed himself–that’s the way it is in war. But, in fact, one of our section was wounded the very first day we got to the Verdun front. He was going out with a driver from [another section]; there were three men in the front seat of the ambulance. They had to cross the plain in front of Dead Man’s Hill–very visible to the German observers. A shell burst near the car, and he had the back of his sheepskin-lined coat cut through, like with a knife, at the back of his spine. He wasn’t wounded badly, but it cut up the column of the steering wheel and went all through the hood. It was remarkable how it hit the car, but it didn’t hurt any of the three men on the front seat. We all found this kind of a shocking experience, though; we’d all gone over to take care of the wounded, not to be wounded ourselves.

IN THE TRENCHES AND IN THE YARD

By the time most American toops arrived at the Western Front, the German army had begun to retreat, and the deadly trench warfare that has become synonymous with World War I had ended. But many of the Harvard students who rushed to join the ambulance services arrived during the final months of the trench war. As a driver for the famous Norton-Harjes Ambulance Corps, Goodhue Livingston ’20 was stationed within the French army on the Somme and Chemin des Dames fronts in early 1917. His career after the war was a varied one: he raised sugar in Cuba, “made pictures for Warner Brothers in Africa,” edited newsreels for Pathé News, “ran for state senate and got beaten,” headed the OSS in southern Africa during World War II, and served as executive secretary to Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York. He is 96 and lives on Long Island. “I think a lot of people nowadays would wonder why the hell anybody wanted to get into the war and get killed,” he says. “But our attitude was, ‘Let’s see what it’s like.’”

Goodhue Livingston was first an ambulance driver with the French and then an officer in the U.S. 15th Field Artillery, until he was wounded in 1918 at Vierzy.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

The battle line of trenches stretched from the North Sea straight to Switzerland, across France and Belgium where the Ypres salient was. The war dragged on and on; attacks would be made to try to take the line of trenches and they would never take more than a few hundred yards. Millions were killed; in the Battle of the Somme a few hundred thousand died in a few days. It was a filthy damn war; men got a leave of a few days and then came back.

The lines were usually divided into three trenches, one after the other, with dugouts. You lived life underground. We would be stationed at about the third trench. They would bring the fellows who were wounded out, on stretchers or limping, and we would have ambulances to pick them up. I had a Ford ambulance, which carried three couchés, which meant fellows lying down, or five assis, which was sitting.

I remember one horrible night when an attack was going on. The ambulances were shelled trying to get up to the trenches; we couldn’t put our lights on. The troops were coming up, and ammunition trains, and God knows what else. You’d get up to your poste de secours, which was the station behind the lines that they’d try to bring the wounded down to.

They’d shove them into the ambulance, and off we’d go to try to find a forward hospital. [During] a hell of an attack, shelling everything, they loaded us up with wounded men, and I started back with a friend of mine driving with me. Then a tire went, and to change a tire was a feat in itself in those days. You had to take the old tire off, and then put a new tire on and put an inner tube in, powder it, blow it up, screw it on. We fixed it up and drove along, and then, by God, another tire blew. Then a third blew. When the third blew, we just couldn’t fix it; we went on the rim. We got up to where the first forward hospital was, took the wounded out, laid them on the ground in stretchers--only to have the medics say, “We’re all full, take them away.” I said, “The hell with you.” So we just left the wounded men there and drove off. That was the kind of war it was.

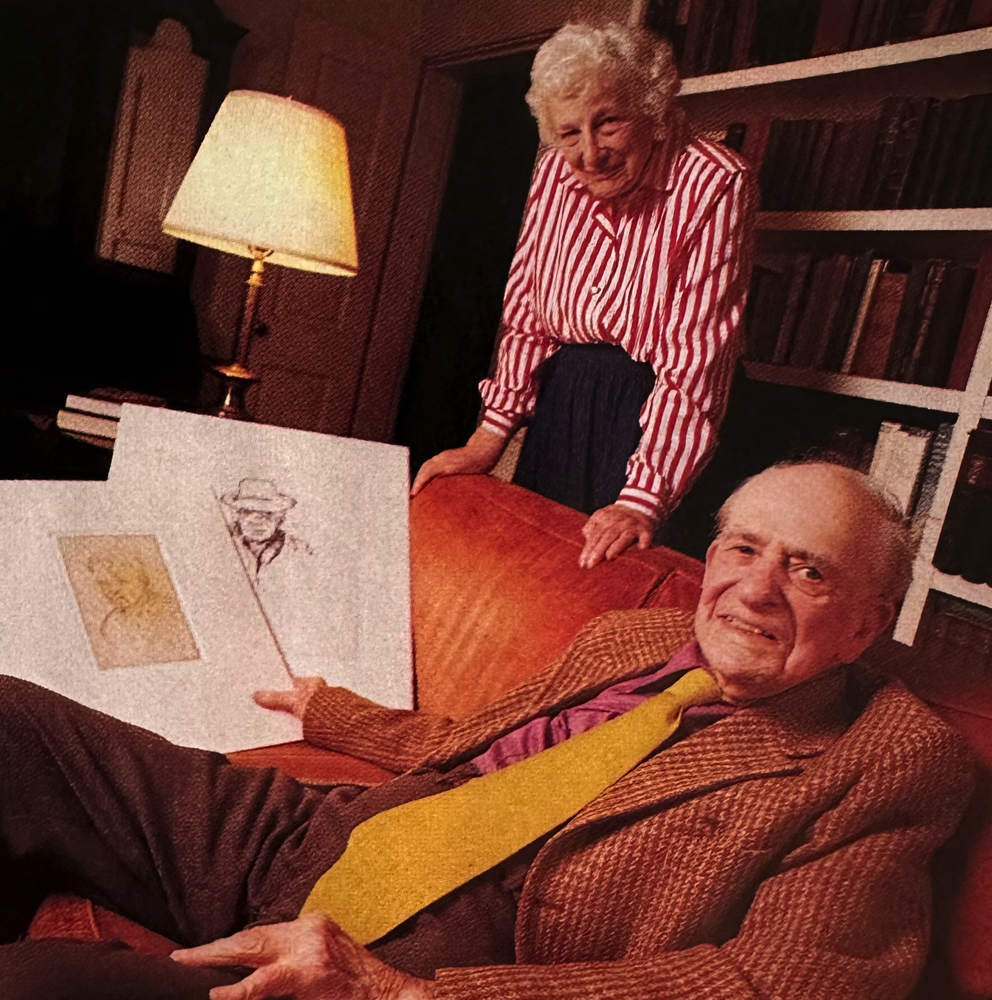

Even those Harvard students who remained in Cambridge found themselves becoming, voluntarily or not, cogs in the American war machine. Between 1915 and 1918, a variety of training corps and military-science courses had undergraduates living in barracks in the Yard and digging trenches around the Fresh Pond reservoir (see “The Ivory Boot Camp.” Harvard Magazine, September-October 1991). Richard Bassett ’20, now 93 and a retired art teacher, was a private in the Students’ Army Training Corps.

Richard Bassett and Eleanor Scott Bassett. They were married on Halloween 1992. With him are two self-portraits; one done at age 18, one six years ago.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

We used to go and drill in the recesses under the Harvard stadium. They didn’t have enough up-to-date rifles to release to us, so we had heavy old rifles that were a survival of the Spanish-American War, the Krieg-Jorgensen, at least six inches longer than the regular army rifles. We had bayonet practice, and we were told to grunt as we stuck the bayonet into an imaginary German in front of us. You had to picture yourself driving this thing in at several targets of the human body that you were supposed to hit. Of course, the one that everybody disliked most was the groin. I decided to put myself down for the artillery, because I’d rather be shot to pieces than be entered by a German soldier with a bayonet.

For some the war was a period of hope, promising democratization at home as well as abroad. Benjamin Ulin ’20, who volunteered for the field artillery in 1918, found that his military experience stood in sharp contrast to the often restrictive amosphere at Harvard. At the age of 94, he is retired from a career as a clothing manufacturer and philanthropist.

Benjamin Ulin with a photograph of Company F of his Harvard ROTC unit, in 1918.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

I’m Jewish, and from the time my friends and I moved into the dormitories, we found we were assigned roommates who were Jewish also. That was the first indication that they thought we ought to be segregated. There was no feeling of anti-Semitism in the classroom—the professors were wonderful and had integrity. But we were kept out of a lot of the old-line Brahmin clubs as well. There were only about two or three Jews in my class who were able to join them, and they could join only if they discontinued their relationships with other Jewish people. That’s why I joined a Jewish fraternity—there was no other wav to function socially. That’s my unhappy recollection. But in the war, we all shared responsibilities, which was fair in a democratic system. There were no racial quotas; we were all citizens of the same country, fighting for the same cause.

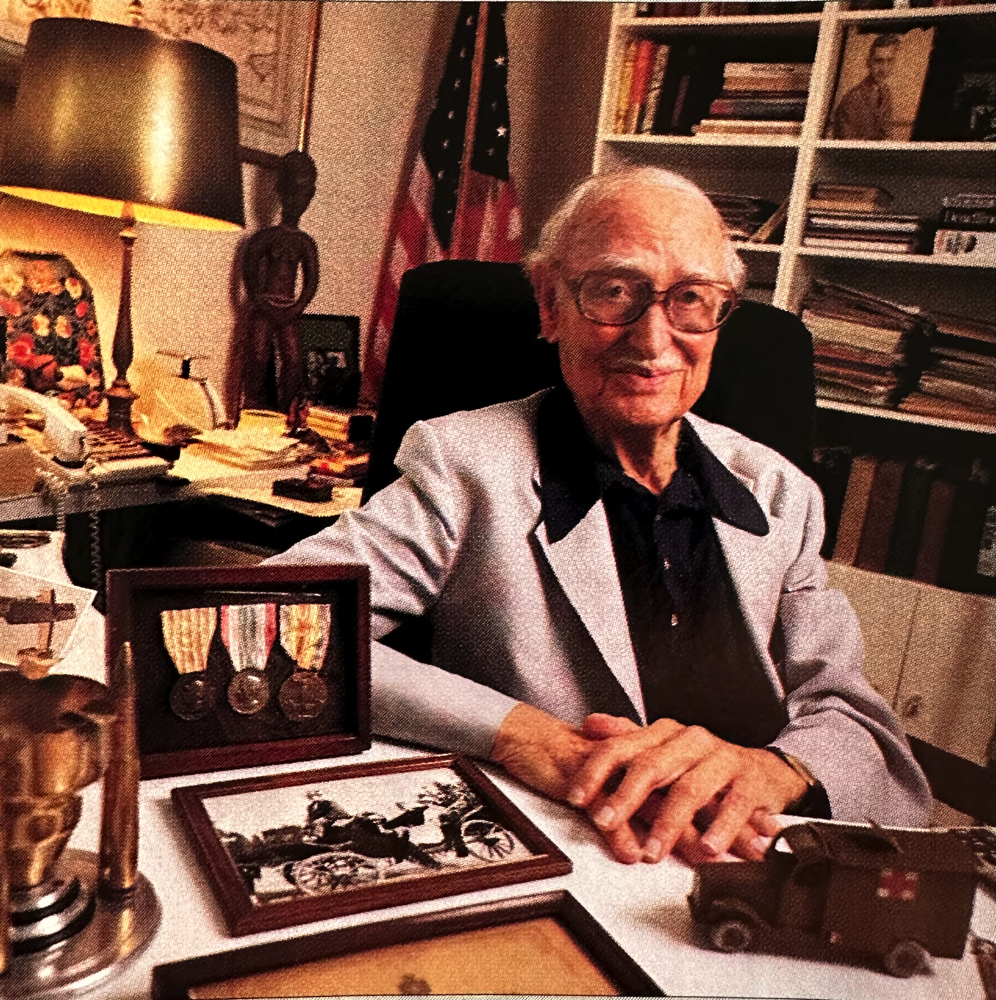

Not everyone was caught up in the pro-war enthusiasm. Horace B. Davis ’20 was one of the few conscientious objectors in his class. Then a self-described liberal, he became a committed socialist after the war and began a long career as a teacher, writer, labor organizer, and civil-rights activist. Now 95, he recently published an autobiography titled Liberalism Is Not Enough.

Horace B. Davis shows a French factory, where he briefly worked that built portable homes for refugees.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

I was doing a lot of thinking about the war and reading about it. I finally concluded that it wasn’t a battle for democracy in any sense, it was just an imperialist trial of strength. It wasn’t like a war against fascism. I argued with my classmates, but I didn’t get anywhere. I felt isolated. It was difficult, but I’ve had the same problem all my life. For most people, the war didn’t affect their political lives as such. They took the war as it came, and it didn’t occur to them to oppose it. They figured that war was something they had to put up with, so they served their time and got out and that was that. I suppose they were affected, but it didn’t change the lives of very many of them. For me, though, the war was a time when I did more serious thinking than any time before or since. I decided to ditch religion, and social reorganization became my leading concern.

Still, the country was at war, and I felt like doing something, not just going back to school. So I joined the Friends Reconstruction Unit, a Quaker organization that was rebuilding towns in France and doing work with the refugees. I was over in France from the fall of 1917 to the beginning of 1919. Most of my Harvard friends went into the army, but although some may have been bitter, most respected my position. I didn’t feel persecuted. In fact, there was one classmate [in the army], Larry Austin, who came to Paris on leave and looked me up, and we went to a play together. Then he went back into the service. He was killed at a quarter past ten on the morning of the eleventh of November, Armistice Day. [The Armistice was signed at eleven.] I miss Larry Austin—he was quite a good guy. We’d been in the same Harvard freshman dormitory together. Politics made no difference in the relationship between us.

The air corps was considered the most glamorous—as well as the riskiest—branch of the military and was known for attracting many lvy Leaguers. Philip Carret ’17 was a ferry pilot in France, delivering planes to the front from depots behind the lines. He still works full time as an investment manager at the age of 96.

Philip Carret in the offices of Carret and Company, where he still works full time as an investment manager.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Flying was very simple; that’s why I liked it. I few mostly the Spad, which was the French pursuit plane, and the Sopwith Camel, which was a very manuverable British plane that I particularly enjoyed, and the Nieuport, which was a slightly older pursuit plane than the Spad. A mechanic would turn the propeller two or three times; he’d say “Contact” and I’d turn the engine on. There was an altimeter for height, and a tachometer for the engine revolutions, and a compass, and that was it. I think the Spad had a top speed of about 130 miles an hour. In modern planes you have to have a flight plan, and you’re under control from the ground all the time. [But then] you just sat in the pilot’s seat and moved the stick as appropriate.

If you couldn’t see the ground, you were out of luck. If you got lost, you flew along the railroad tracks at about a hundred feet and tried to read the sign on a station. That was called hedge-hopping. It was a lot of fun. You’d come to a row of trees and jump over ’em. Not recommended from a safety standpoint.

Very fortunately for me, I never got shot at. But there was a certain amount of risk, of course, just in flying in those days. In the airfield where I was stationed, we lost one pilot in a crash out of thirteen. And I saw a couple of French pilots killed when I was at gunnery school. Their planes collided in midair. I watched them spin down into the ground and, afterward, saw a mechanic clean their brains out of the wreckage of the planes. But those were isolated incidents; at the front they had that kind of thing all the time.

Although officially too young to be commissioned, Goodhue Livingston used a letter of recommendation from Theodore Roosevelt, a family friend, to become a lieutenant in the field artillery. He participated in the final Allied offensive against Germany in 1918.

Suddenly we had gone from trench warfare to open warfare. We had the Germans on the run starting around the eighteenth of July and were following them up. Our unit, the Fifteenth Field, was then behind the French Moroccan troops.

Somebody originated kind of a crazy idea: that in the next advance, one of our batteries would follow the infantry forward and lay down a shellfire barrage, and then another would come behind and follow them again. Well, it didn’t quite work, because the Moroccans got stopped and started to retreat. We were left sitting in an open field, and the Germans had us practically under direct fire. We just had to get the hell out—three of our four guns got left behind. It was a hell of a mess—pretty many got killed and wounded in that show. We retreated back behind a hill, a place where it was hard to direct the shellfire. A shell came in and wounded me. Killed my horse. The horse was standing between me and where the shell fell, so the horse was demolished, and I was just hit in the leg,

We had one gun left, so that night the captain came by and told us to go out and bring in the other three guns—I was detailed. It was a moonlit night, so we did find the guns and tied them up. We found a French tank coming back, so we tied the guns to the back of the tank, and the tank towed them in. I went into a foxhole and lay down to go to sleep. The next morning I couldn’t get out of the hole–my leg had swollen up with gangrene.

The earth in France was horribly infected with something that got this poison into your wounds. I was evacuated on a truck that was making motion pictures for the French government, since there weren’t any ambulances around. I was very lucky my leg wasn’t amputated.

LOVE AND WAR IN ITALY

For one group of Harvard students, the war was their summer vacation. In May 1918, 37 undergraduates—mostly freshmen and sophomores—joined the American Red Cross Ambulance Service as drivers on the Italian front. They were posted together at Bassano during the last great Austrian offensive and were back in Cambridge in time for the fall semester: Among them was the late Charles W. Eliot 2d ’20, M.L.A. ’23, grandson of Harvard’s former president. A conservationist and city planner, he died last March at the age of 93.

When a recruiter for the Ambulance Service came by, I signed up promptly and persuaded lots of my friends to join also. Shortly after I signed up to go to Italy, I got a note under my dormitory door, “Report to President Lowell’s office.” He wanted to know why I was going and persuading my classmates and friends to go with me, because he’d already got French officers over here to train Harvard students to be American infantry officers. I told him “Yes, I understand, Mr. President, but I cannot be an officer until I am 21 years old; now I’m just eighteen, and I want to do my share.” From President Lowell I then heard a long, loud “Harrumph!” and knew I was dismissed. So on the fourteenth of May, we sailed from New York and went to Bassano in Italy, on the western edge of the Venetian plain, right under Monte Grappa. We were assigned to different posts to serve the different hospitals on the plain, and different posts on the mountain; we drove Fiats and Ford ambulances.

W. Houston Kenyon ’21, J.D. ’24, was also with the Monte Grappa ambulance unit. Now 94, a retired patent lawyer, he lives in in York City.

Houston Kenyon. The photograph at left shows his ambulance, himself, and the late Charles J. Young ’21.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

The fighting was all on the top of the mountain. The road went up that mountain, sixteen miles of winding back and forth to get to the very top. We had some very, very exciting experiences. The one I remember best was when I came as close to getting hit by a big shell as I guess anybody ever did. I was on a roadside that was cut from the hillside on the side of the mountain. I’d heard the whistle, and I fell into the ditch. A big shell hit right on the steep bank above me. And the two things I will never forget are the smell of cordite that was in my nostrils almost immediately afterward, and the avalanche of gravel that came over the hill and over-jumped where I was. I had driven an ambulance up to that spot and had stopped—the road was all messed up with previous hits. I’d gone up with John Fiske, another Harvard man. We backed out with our full load of wounded and went back a little way and ran into another one of our ambulances, this one piloted by Charlie Eliot and an older man. We got out finally by taking another route that was really an animal trail, the most fantastically dangerous thing you ever saw to try to handle an automobile on.

Four years later I was traveling through Europe with a classmate of mine who was not in the ambulance service, and we decided to go from Venice to Bassano and hire a car there for the trip up the mountain—sixteen miles. So we went up. It was a terrible day: rain and fog. All I can remember about the battlefield is that men were up there pounding up barbed wire into bales to sell it for junk. But right down at this bridge on the road, right by where we’d been shelled, was a brand-new monument, an ancient fluted column mounted up there and it said on the front of it, in Italian, “Gift of the citizens of Rome, this column marks the high-water mark of the Great War, June 25, 1918.” That was the day that the three of us were there: John Fiske, Charlie Eliot, and I. [John Fiske ’21, a retired banker, died in 1986].

One of the drivers at Monte Grappa, although he didn’t realize it at the time, witnessed literary as well as military history in the making. Henry S. Villard ’21 fell ill and was sent to the American Red Cross Hospital in Milan, where he befriended another young ambulance driver: Ernest Hemingway. Then only nineteen, Hemingway had been wounded by a shell and was recovering in the hospital, where he was also carrying on a romance with one of the American nurses, Agnes von Kurowsky. The experience later became the basis for the novel A Farewell to Arms. Villard makes a cameo appearance in Chapter XVII as “a nice boy, also thin, from New York, with malaria and jaundice.” A retired diplomat, he served as U.S. ambassador to several African nations and recently coedited Hemingway in Love and War (Northeastern). He never saw Hemingway again after 1918.

Henry S. Villard. By healing before Hemingway, he won a date with Agnes von Kurowsky (in the photograph before him).

Photograph by Jim Harrison

As soon as I was well enough to get out of bed, they introduced me to my next-door neighbor. It was Hemingway. We hit it off immediately. He was a very attractive fellow in those days: very magnetic, very good-looking, congenial—attractive to both men and women. We spent hours and hours chatting; since he couldn’t move, I spent a lot of time in his room with him. We talked a lot about his favorite subject, which was baseball. My favorite team was the New York Giants and his was the Chicago White Sox, and we followed the scores as best we could. We were just teenagers, really. Of course, we talked a great deal about the Italians—in the hospital we could express our opinions freely, since there were no Italian patients. We both had a pretty dim view of the Italian capabilities. Being patriotic Americans, we were very proud of what the American troops were doing in Europe, but over all hung the shadow of the defeat at Caporetto. The Italians are not born fighters, or at least they weren’t in those days. They were much better at picking up a mandolin and singing than at picking up a gun.

He was drinking in the hospital more than any of us. He’d ring the janitor to bring him up bottles, which he hid under the pillow. When I came into the room he’d offer me a drink out of the bottle. It was strictly against the rules and the subject of great animosity between the superintendent and him. When she found out about his drinking, he became Enemy Number One. Of course, he was already a kind of bull in the china shop in the hospital—he had an authoritative way about him. He’d boss the nurses around; he was rather demanding and difficult. He was different from the other patients; he was thought of as something of a character. But people enjoyed him. He didn’t ever mention the idea of writing fiction.

Agnes was the most attractive person imaginable. She was 27 years old and we were eighteen and nineteen, and she seemed very attractive to me, too. I had a crush on her; we all did. People joked about it a little, that Agnes was paying more attention to Ernie than to any of us. He wanted her by his bedside whenever he could think of any excuse. Agnes later on denied that it was anything more than a girlish flirtation, but I suspect that her feelings ran deeper than she admitted.

I read A Farewell to Arms when it first came out, in 1929. The names were different, and the girl was English instead of American, but essentially it was the story of Hemingway’s love for Agnes. In my opinion, he never got over that early love affair; I’m convinced that if circumstances had allowed it, he would have gone back to her and married her. The only part of his portrait of her that was inaccurate was the extreme sexual permissiveness—there was nothing like that. She later said to me, “I wasn’t that kind of girl.” That was the truth; the affair was never consummated in any way. By and large, girls weren’t like that back then.

I wrote to Agnes at her home in Florida sometime in the 1970s and enclosed a snapshot taken of the two of us, in case she didn’t remember me. I asked how she’d fared since those memorable days in Italy. She was delighted and wrote back immediately, and we started a correspondence that lasted the rest of her life.

I was living in Switzerland at the time, and she asked me to look her up if I came to the States. I did just that and came to Florida, where we spent a couple of days of very interesting reminiscing. She had changed a great deal; I suppose I had, too. She was at a fairly advanced age, she had not been well. I suppose if I had met her in the street, I would not have recognized her as Agnes von Kurowsky. But her manner was the same. A few years later, toward the end of her life, she wrote to me about her great wish, which was to be buried in Arlington Cemetery (she had been denied permission). I did what I could, and when she died the next year she was buried at Arlington.

ARMISTICE AND AFTER

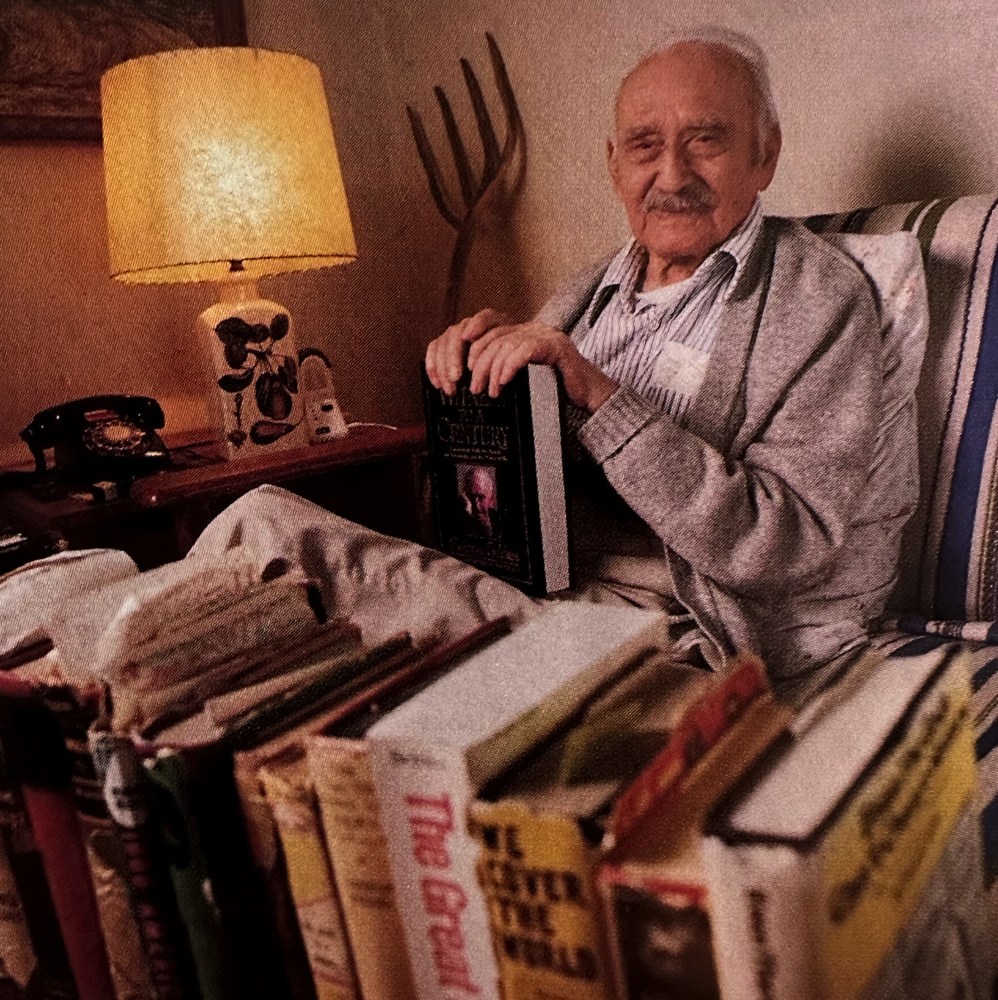

On November 11, 1918, when the guns on the Western Front stopped firing, George Seldes ’12-’13 was there. A correspondent for The Chicago Tribune, he was covering the war as a member of General Pershing’s press corps. Seldes is now 103; his writing career spanned nine decades, and he published his last book, Witness to a Century, in 1987.

George Seldes with his latest book, Witness to a Century, and the 23 others he has written.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

It was unseemly, very strange; all during the war you could hear the big guns, even in Paris, boom-boom-boom-boom. It was like something going on in the air. And then suddenly things got quiet, and it was a very frightening quietness for a while. I got back to Paris [later that day], and from the steps of the Opera House we could see the Avenue de l’Opéra, and all the way down it the crowds were enjoying themselves, yelling and shouting and singing and dancing. You couldn’t get into a café. That was an exciting time, Armistice night in Paris. By heck, somehow we got into Maxim’s. There was some guy, an American in uniform, mounted on a table addressing all the drinkers, half drunk himself. And I remember very clearly standing on the steps of the Opera, and a doughboy kept poking me and saying, “Mawnsoor, où est l’Opéra?” I kept saying, “You’re standing on the steps,” but he didn’t listen to me.

Across the Atlantic, Harvard’s student army had its own Armistice celebration. Richard Bassett participated.

We went down to Boston to celebrate, marching down Tremont Street behind the Harvard band. Everybody was embracing everybody else down there. Tremont Street was a seething mass of people celebrating, kissing one another. The rifles were very heavy to carry, and it was very cold. But as a matter of fact, I rather liked the army under those conditions.

People you had never seen in your life came up and kissed you, especially since I was in uniform. It was absolutely sincere; everyone was just happy the whole thing was over.

In the days following the Armistice, George Seldes and several other correspondents at the front began to get restless. They decided to seek an exclusive interview with Paul von Hindenburg, the German commander in chief.

The law was that anyone who broke the Armistice by crossing over the lines would be court-martialed and shot. We decided that didn’t apply to newspapermen. So we drove right through Luxembourg and on the other side we came upon the entire German army in confusion, disarming.

A German colonel said “Take these four American prisoners out of their car and shoot them. We can use the cars.” We were driving Cadillacs.

Luckily for us, another man said, “I’m in command here,” and it was a sailor from Kiel. [Sailors from Kiel had mutinied and established a German republic in the last days of the war.] He said to the colonel, “Don’t you know that we’ve established a republic? You mind your business and go back to the business you’ve been assigned to; continue with your work of demobilization, and I’ll continue with my work putting bastards like you in jail for forgetting your place in the new German republic.”

They had us send the Cadillacs back, and they gave us a German car—it had ropes on the wheels instead of rubber tires. They didn’t have a single piece of rubber in the whole country. We couldn’t do any more than five miles an hour. But finally we got to Hindenburg’s headquarters [in Kassel]. We stopped at a hotel, because Hindenburg wouldn’t recieve us. We went there day after day. And we gave up and got ready to drive back when the manager of the hotel asked what the trouble was, and we told him. He said, “I’m in charge in this town.” So he called up and said, “Tell General Hindenburg to send his best automobile. There are four American newspapermen here, and they’re going to get an interview.” So the next day, there was a beautiful car with real tires.

So we went and were very nicely received, and had a wonderful interview with Hindenburg. He said the war had come to a stalemate and there had actually been feelers put out on both sides about calling the war off and returning to the status quo ante, saying, “It’s been a great mistake on both our parts, and now it’s over.” But, he said, “just when we were about to call the war off, a fresh young army sprang out of the Argonne, the American troops. And what else could I do but ask for an armistice on the Allied terms?” He said the American army had won the war. And Hindenburg started to cry. Yes, and that was a great sight, to see tears coming to his eyes, and him wiping the tears from his eyes; and he said, “Mein armes Vaterland, mein armes Vaterland.. [“My poor fatherland, my poor fatherland...”]

That interview was never published. There was so much jealousy among the press section that a group led by Eddie James of the Times persuaded Pershing to issue an order saying that we were never to publish the interview with Hindenburg.

And he actually had us arrested and told Pershing he wanted us shot as an example for anyone who tried to cross the armistice line. But we appealed to Colonel House, and he saved us from being court-martialed.

THE WORLD THE WAR DESTROYED

Henry Villard is now 93.

The war changed everything. There was a decline in morals that began with the Roaring Twenties, which really shook up the structure of society and led to a new permisiveness, to the beginning of cynicism. The war suddenly reversed the whole trend of the century. It laid the seeds for World War II. But for me, it was probably the most important thing I ever did in my life.

After 1918 the world would never be the same. It was a dream world before; it was a world not real by today’s standards. Life was well ordered, quiet. There were no telephones to speak of, no radios, few motion pictures. It was a sort of horse-and-carriage existence, very unrealistic when you compare it to today. But nonetheless, it was a very nice world.

Alexander Cameron ’17 entered naval radio school at the end of his senior year. Now 98, he lives in Florida.

When we first went into radio school, after we’d been there about two months, and I’d gotten good enough to handle ordinary messages, they called all the companies to attention and asked for three volunteers to go to Maine and man a radio station on a little island twenty miles offshore. Nobody budged at first, but then one of my good friends said, “Sandy, how about it? Let’s try it out.” So three of us volunteered, and they took us up to Rockport in a big launch. We were there all summer. There were just fifty familles on that island, and some of the people had never been ashore. They’d never seen an automobile, never seen a trolley car, all the things that we just took for granted. They were very nice to us. One of my pals happened to play the guitar and I played the mandolin—we’d get up a little entertainment on Saturday nights. It was still the ninteenth century on that island. The war shook that world up a lot; people began to travel around more, to see things, to read about what was going on. That came very fast. But we were there before all that.

Adam Goodheart graduated from Harvard College in 1992. He spent the next year on a Shaw Traveling Fellowship, working on archaeological digs in Sicily and writing. The format of this article was inspired by Studs Terkel’s books. Goodheart says he likes oral histories because they evoke “not just a past time, but also the time that has passed since then.” Photographer Jim Harrison is a contributing editor of this magazine.