As such, it takes study abroad "beyond its originally conceived role" in promoting advanced language study, according to the legislation's principal champion, William L. Fash, Bowditch professor of Central American and Mexican archaeology and ethnologythe rationale being that "the best place to study tropical-forest ecology is in tropical forests," as he put it. Thus, the faculty encourages, but no longer requires, language study; shifts the presumption away from insisting that foreign study be a unique opportunity beyond Harvard offerings; and moves from custom-crafted programs toward approved ones in which a student could enroll as of right. The intent, Fash said, is to make study abroad "an invaluable part of undergraduate education for all Harvard College students."

Implementation will depend upon identifying accepted programs, concentration by concentrationa possibly time-consuming task. One partisan who will keep the heat on is President Lawrence H. Summers, who told a March panel on globalization, "I look forward to the day when essentially every undergraduate student has a meaningful foreign experience during their time in college"and the remoter and less developed the foreign country, the better. Another will be FAS's new dean, William C. Kirby (see "An Asia Expert for Arts and Sciences"), who led the faculty along with Fash. He is enthusiastic about new courses being taught abroad by faculty members and language instructors in summer school this yearpart of a "culture of experimentation" on study abroad he intends to encourage.

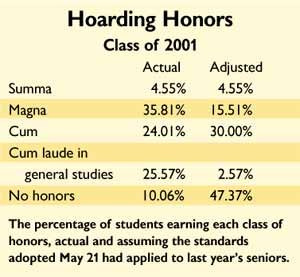

While away, the students had better study instead of play. At its May 21 meeting, the facultyannoyed that 90 percent of College students currently graduate with Latin honorsimposed a new percentage-based regimen. Qualification for honors in a subject will still depend on nomination by the concentration and high grades overall (demonstrating a student's general education). But along with existing limits on the number of summa cum laude honors (up to 5 percent of the class), there will now be effectively a limit of 15 percent on magnas, and another 30 percent for cums. The existing cum laude status for overall grades, where a student does not pursue or is not recommended for concentration honors, will persist, but at the magna grade average, and will be restricted to no more than 10 percent of graduates. The new rules apply to the class of 2005.

The effect, Pedersen said, will be to restore the "pyramidical" structure of honors, which had become misshapen (magna became the most commonly conferred honor), and to "cascade" the awarding of honors downward. Were the new standards applied to the scholars graduated in 2001, nearly half would have commenced without benefit of any Harvard Latin honors (see chart).

Finally, in an initial response to perceived grade inflation, the faculty tossed out the 15-point grade scale and adopted the more common 4.0 scale, ranging from A and A- (4.00, 3.67) through D- and E (0.67, 0.00). The change may influence grading practices, in that the current scale has an odd gap (A- is a 14, for instance, but B+ is a 12, and so on), which may make some professors reluctant to award the lower grade. But it is not accompanied by a mandatory curve or other constraints on faculty practices. Pedersen's office will circulate information on exemplary grading practices to all departments, and will monitor the grades actually awarded by departments and individuals as a sort of anti-inflationary presence.

Why would Harvard do something so prosaic as to adopt a grading system in common use? Because, Pedersen said, she was persuaded it would be stupid to "replace one untransparent, idiosyncratic Harvard scale with another untransparent, idiosyncratic scale." Now students will even be able to apply for graduate school without having their transcripts translated first. The new system goes into effect for the 2003-2004 academic year.

Before then, however, grading may be debated further. While endorsing the change, Summers noted that he hoped for more work to address concerns about "compression" (the usefulness of grades to distinguish among students in a class) and equity (Pedersen's data uncovered marked differences in grading among the academic divisions today).

Such discussion might well be warranted. In its May 24 issue, published on the last day of final exams, the Crimson's "Roving Reporter" asked, "How will Harvard's changes to grading and honors policies affect your study habits?" Among the respondents, Daniel B. Tomlinson '03 replied, "Well, if I had study habits..." and Timothy M. Coleman '02 offered, "My current 3.0 on a 15-point scale GPA could be perceived as a B."