Zelia Nuttall signed letters to her friend and mentor, Frederic Ward Putnam of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnography, “your goddaughter in Science.” Her intellectual instincts were those of a scientist—to explore, to observe and record, to collect and categorize and explain. She was just 29 years old when Putnam, one of the founders of modern anthropology, asked her to be special assistant in Mexican archaeology for the museum, a title she would hold for 47 years. Their friendship lasted a lifetime.

Zelia Maria Magdalena Nuttall was a protagonist in the late nineteenth-century effort to respond with scientific rigor to a centuries-old puzzle: Where did ancient civilizations come from? Born in San Francisco in 1857, she was drawn to Mexico, the homeland of her mother, determined to uncover its history. With extraordinary care, she tracked down ancient codices, texts, and artifacts, many of them scattered across Europe during and after the Spanish conquest, to explore how they illuminated the history and practices of pre-Columbian cultures. For almost 50 years, she worked to ensure that America’s museums and universities gave significant attention to the richness of its past.

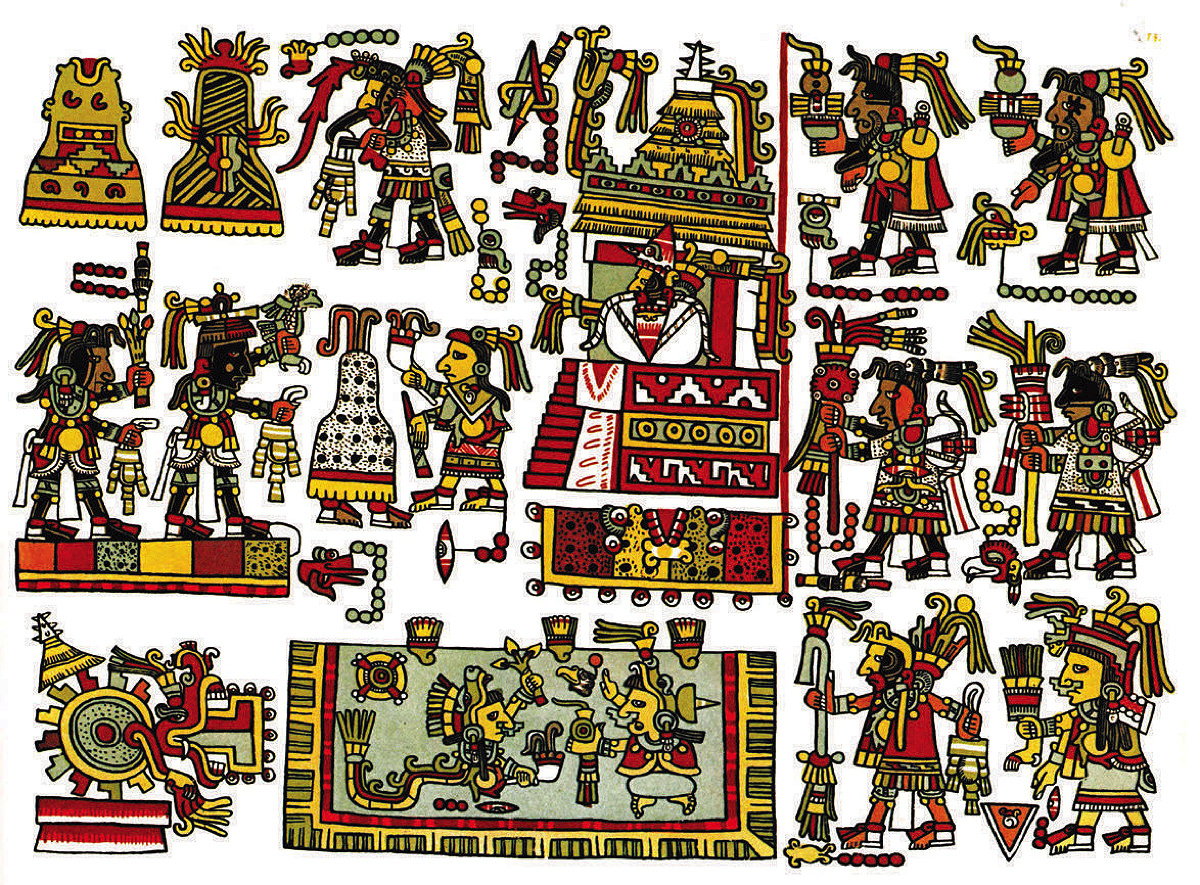

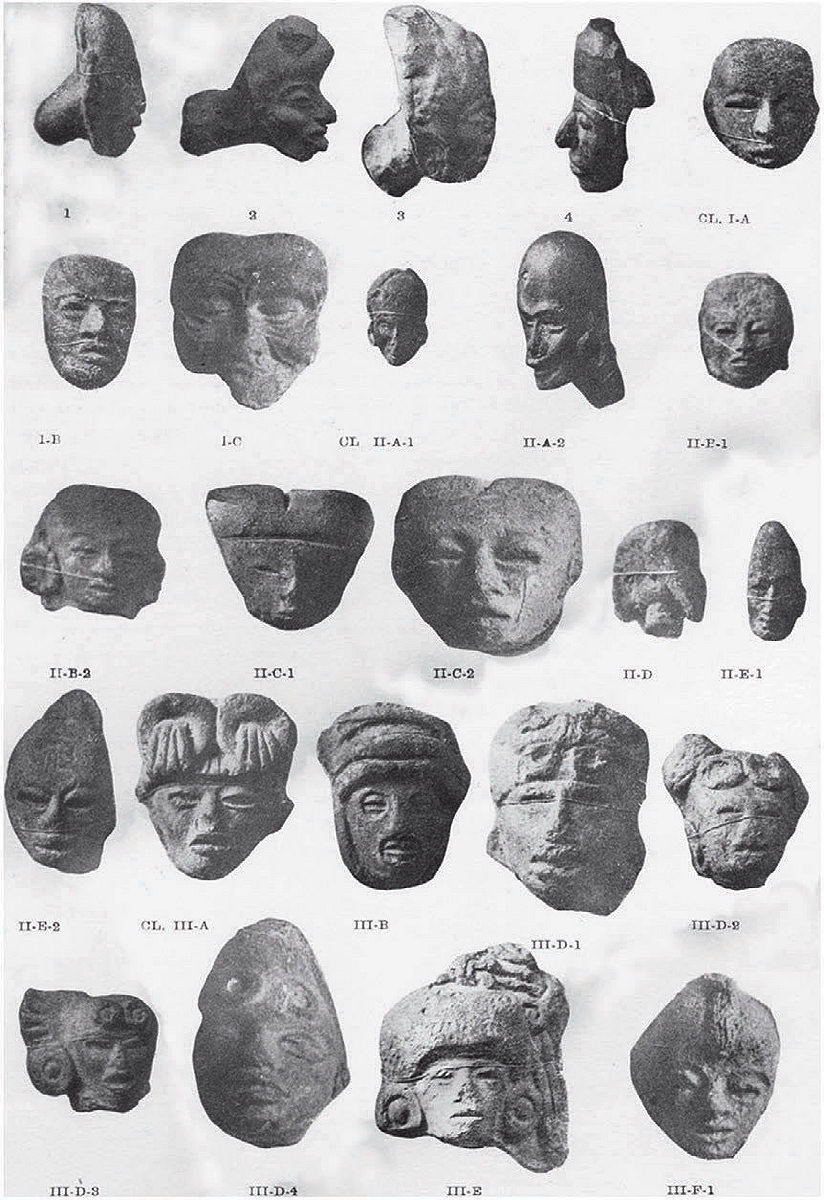

Few today remember Zelia Nuttall, but from the 1880s to the 1930s, she was famous, invited to speak at international conferences, quoted as an authority on ancient Mexican cultures in national and international media, and known to presidents, kings, and queens. Her first publication, an exploration of small terracotta sculptures from central Mexico, demonstrated her exceptional skill in linking artifacts to rituals and beliefs of bygone civilizations. She subsequently made history by decoding the Aztec calendar, interpreting stories told in colorful codices, and locating a sixteenth-century journal that shed light on Sir Francis Drake’s travels. At one “Eureka!” moment in the British Museum, she came across an indigenous pictorial history that pre-dated the Spanish conquest. It became known as the Codex Nuttall, and the Peabody published an exquisite facsimile under her direction. She identified a new period in Mesoamerican history, the Archaic, and knew, as few others did, the pottery, poetry, and gods of the Aztecs and their predecessors, their myths, and the stars they watched to regulate their ceremonies and daily activities. She cultivated plants from Mexico’s early kingdoms and wrote about the elegant gardens and waterways of the Aztecs. In the late 1920s, she promoted a new holiday in Mexico, an annual commemoration of the sun’s “shadowless moment” that had once been observed by the ancients.

Nuttall’s influence was felt at Harvard, where many of her articles were published, at the Universities of Pennsylvania and California, and at the National Museum of Mexico, as each of these institutions assembled valuable collections from pre-Columbian civilizations. She championed Mexico’s first professional anthropologist, Manuel Gamio, and counted notable anthropologists such as Franz Boas, Alice Fletcher, Alfred Tozzer, Alfred Kroeber, and Alfred Maudslay as trusted colleagues. She was celebrated at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 and chosen as one of the three most distinguished women in America in 1915. Nuttall was also famous for her acrimonious showdown with Leopoldo Batres, who used his power as the head of Mexico’s department of antiquities to thwart her desire to excavate on the Island of Sacrificios, three miles off the coast of Veracruz, in order to seize the glory for himself. Assertive and acerbic, she regularly scorned views contrary to her own—and was usually proved correct.

Nuttall spent much of her life as a nomad, a divorced single mother traveling widely in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. In 1902, she settled in an eighteenth-century palace in Mexico. There, her Sunday teas at Casa Alvarado drew members of the country’s elite, aspiring anthropologists, and visiting dignitaries who came to peruse her collection of artifacts and stroll in her fragrant garden. Mrs. Norris in D.H. Lawrence’s The Plumed Serpent was a fictionalized Zelia Nuttall, who “put her visitors uncomfortably at their ease” as they navigated the treacherous waters of relations between the United States and Mexico. Her writing conveyed profound respect for the accomplishments of the Aztecs and their predecessors in art, architecture, engineering, medicine, astronomy, religion, and agriculture, abjuring many of the assumptions of her time about the linear progression of civilizations and races from “savage” to Western modernity.

The nineteenth century welcomed amateurs into the fold of anthropology, including some notable women encouraged through Frederic Putnam’s “correspondence school” of aspiring scholars. By the 1920s, however, a new generation of university-trained researchers began to consider Nuttall a relic of a less professional past. Bravely, she countered them, insisting that they recognize the importance of the discoveries she had made. After her death in 1933, she was honored as “one of the outstanding figures in American archaeology and history.” Harvard’s Alfred Tozzer remembered “her majestic presence, her wit, and her knowledge.” Zelia Nuttall, a remarkable pioneer who helped build the foundation for our understanding of Mexico’s remarkable past, deserves to be remembered today.