Clayton Christensen’s book, How Will You Measure Your Life? (2012; with James Allworth and Karen Dillon), focuses on values and offers its readers guidance in aligning their choices, professional and otherwise, with the things that genuinely matter to them. He does as much in his own life, which enables him to live in a way that one might describe as whole-hearted.

Born in Salt Lake City, Christensen grew up in a Mormon family and served as a missionary in South Korea from 1971 to 1973; he speaks fluent Korean. He earned a summa cum laude degree in economics from Brigham Young University, then attended Queen’s College, Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar, where he received an M.Phil. in applied econometrics and played some basketball, as he had in college. (He stands six feet, eight inches, and remarks, “I’d rather play basketball than eat.” His six-foot, 10-inch son Matt played on the 2001 NCAA championship team at Duke.) Christensen was a Baker Scholar (a top academic honor) at Harvard Business School, and became a White House Fellow in 1982, serving as an assistant to secretaries of transportation Drew Lewis and Elizabeth Dole.

He and his wife, Christine, have raised their five children in a reverently Mormon household. In 1999 he wrote a short essay, “Why I Belong and Why I Believe,” as a gift to his children; it appears under the “Beliefs” section of his website, www.claytonchristensen.com. There, he writes that the mechanism by which the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints has helped him understand and practice the essence of Christianity is “to have no professional clergy. We don’t hire ministers or priests to teach and care for us. This forces us to teach and care for each other—and in my view, this is the core of Christian living as Christ taught it.” He describes the many ways daily life offers him opportunities to serve others, whether it be helping unload someone’s moving van or visiting an elderly couple, in poor health and struggling with alcoholism, who lived in a dilapidated apartment in a rough part of Boston.

The essay also relates how, as an Oxford student in 1975, Christensen began a nightly practice of reading the Book of Mormon from 11:00 p.m. to midnight, combined with prayer and an inquiry to God as to whether what he was reading was in fact His truth. One October evening, “I felt a marvelous spirit come into the room and envelop my body. I had never before felt such an intense feeling of peace and love.” The spirit stayed with him that entire hour and returned each night thereafter. “It changed my heart and my life forever.”

In the Mormon Church, he explains, “We truly believe that we are children of our heavenly parents. When that’s your mind-set, you regard people in a different way. If you’re starting a company or running a company, and you recognize that the people you are working with are children of God, you’re much less inclined to disparage them, or not try to help them become better people.”

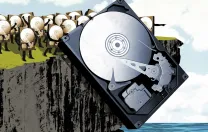

Regarding missionary work (his 2013 book The Power of Everyday Missionaries explores this topic), he draws an analogy with the healthcare industry. (Christensen likes to use business metaphors in religious contexts; he says the early Christian church went on “a merger and acquisition spree” and notes that “there’s an enormous amount of non-consumption in understanding God.”) “In order for people to make good choices, they have to understand what the options are,” he says. “The Kaiser Permanente health plan, in California, has a much better system for providing higher-quality and lower-cost care, by any measure. Members stay in the system for 18 years, on average, for example. So imagine that Kaiser Permanente just stayed out in Northern California and didn’t tell anybody about how to do it better—while the rest of America falls off the cliff into low-quality, very complicated, and expensive healthcare. It wouldn’t be right. They need to speak up and say, ‘There’s a better way to do things, you guys.’ In a similar way, as Mormons, we need to talk to other people about what we believe. It’s not that we’re trying to impose something on them, but if they don’t understand that this is an option, they can’t choose.”

Christensen became a major consumer of healthcare in his own right after a harrowing period in 2010, when he suffered a heart attack and then was diagnosed with follicular lymphoma, a systemic cancer that had resulted in three large tumors. Just as he was finishing chemotherapy, he suffered a serious stroke while giving a talk in church. Luckily, a neurologist in the congregation instantly recognized what had happened when Christensen’s speech turned to gibberish, and drove him to the hospital. “Had I not been close to great care with any of these events, I would have passed away,” he says.

These brushes with mortality “sure have given me a lot of opportunities to think,” he continues. “It’s been posed to me: maybe this is the end. But I’ve been able to say to myself, and to my family, that if God needs me more on the other side, I’m ready to go. I’m not ashamed of how I’ve lived my life, and it actually hasn’t caused me to reprioritize anything, other than wanting to do more good for more people.”

How Will You Measure Your Life? tells of a company picnic for employees at the advanced-materials company Christensen ran in the 1980s. He saw a young scientist, Diana, and noticed the joy and love she shared with her husband and two young children. For the first time, Christensen was able to locate her in the larger context of her life, and to call up a vision of how a day of positive experiences and support at work could send her home with “a replenished reservoir of esteem that profoundly affected her interaction with her husband and those two lovely children. And I knew how she’d feel going in to work the next day—motivated and energized. It was a profound lesson.”

The lesson, he says, was that “for the first time in my life, I realized that I had always wanted to help other people. Until then, I’d framed it as, ‘If you really want to help people, you should study sociology.’ But I realized: sociologists just talk. If you really want to change people’s lives, be a manager. You have an opportunity, for 10 hours each day, to structure their work so that when they come home, they have a higher degree of self-esteem, because they accomplished something that matters to people.”