In May 1968, the university’s students wanted to change the world. Left-thinking ideologies like Maoism and socialism were in their minds, and “Vietnam” was on their lips. They went on strike, skipping classes and exams. They rioted and clashed with police. One student was killed, 900 arrested.

If this sounds like a scene from Kent State, where student demonstrators were killed two years later, that is because the May 1968 unrest at the University of Dakar in Senegal was part of the same general mood around the world that moved students to protest, says Omar Gueye, professor of history at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar. Gueye spent six months at Harvard during the 2013-14 academic year as a postdoctoral fellow at the Weatherhead Initiative on Global History (WIGH), a program premised on the belief that events like these—not unlike the seemingly contagious uprisings of the Arab Spring—can be fully understood only in a global context. As elsewhere during the student protests of the late 1960s, local factors played a role in Dakar: government cuts in scholarship funding precipitated the strike. But student anger tapped a deeper sense of injustice as well: although French colonial rule had ended in 1960, the university was still French, Gueye explains, and the French military was still stationed in Dakar. “Vietnam”—another former French colony—therefore had a specific resonance among Senegalese students, who felt a sense of brotherhood with the Vietnamese.

Historians increasingly recognize that trying to understand the past solely within the confines of national boundaries misses much of the story. Perhaps the integration of today’s world has fostered a renewed appreciation for global connections in the past. Historians now see that the same patterns—colonialism, or the rise of small elites controlling vast resources—emerge across cultures worldwide through time, and they are trying to explain why. “If there is one big meta-trend within history, it is this turn toward the global,” says Bell professor of history Sven Beckert, who co-directs WIGH. “History looks very different if you don’t take a particular nation-state as the starting point of all your investigations.”

The rise of a global perspective is one of several trends that are changing the way history is studied and understood. The increasing use of science to illuminate the past is another. Goelet professor of history Michael McCormick leads the University’s Initiative for the Science of the Human Past, which has engaged a range of collaborators: from geneticists and chemists elucidating patterns of migration using DNA and isotopes, to climate and computer scientists using ice cores and Christian texts to parse the rise and fall of civilizations. In the Joint Center for History and Economics, Knowles professor of history Emma Rothschild has, as director, revitalized this third realm of historical research (which dates to the 1890s in the United States and Britain). Scholars there embrace new quantitative methods such as network analysis to enhance historical inquiry (see “Examining Economic Webs,” page 56); by undertaking collaborative projects—such as studying the history of energy—they are contributing freshly relevant understanding to some of today’s most pressing problems.

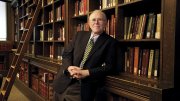

These three projects differ significantly, notes Adams University Professor emeritus Bernard Bailyn, “and they have very little directly to do with each other. But together, they create enough intellectual energy in the history department to light a midsized city.”

Fractal History

“In this contemporary moment in which the world is becoming ever more globally interconnected,” says Beckert, “historians can’t help but observe that a global perspective might also be a useful way to understand the human past. We have spent the past hundred years looking at history within a nation-state framework, and there are limitations to that.” By looking beyond these boundaries, he points out, “an entirely new history opens up.” His WIGH co-director, Saltonstall professor of history Charles Maier, notes that global history allows scholars to consider common challenges facing all of humanity, such as climate change or disease. “Or you can consider the impact that societies have on each other, sometimes referred to as ‘entangled history’ ”—why, for example, students around the world rose up in the 1960s in protest against social norms. A global perspective also makes possible the study of events such as migrations from one nation or region to another. Says Maier, “It opens you up to all kinds of questions.”

The Weatherhead initiative, collaborative to its core, attracts scholars from around the world. Faculty members, undergraduate and graduate students, and post-doctoral fellows meet weekly to discuss their research projects and to seek insights from their colleagues, often expert in the same fields, who work in the context of other countries. This past spring, Maier sought comment on a draft chapter of his forthcoming book on changing concepts of territoriality. He heard from scholars rooted in a variety of countries and eras, ranging from an undergraduate to a visiting postdoctoral fellow who studies Franciscan monks, members of a mendicant order of the Catholic church with an abstemious relationship to both property and territory, who established missions worldwide in the Middle Ages (see “Alternative Histories,” below).

The idea, says Beckert, is not just to write global history at Harvard, but to seek alternative perspectives from scholars in other parts of the world, especially voices of scholars from the global South, who often have pioneered the field without being heard in the West: “This relates to the internationalization of the University. We bring a dedication to the study of other parts of the world, but we are also very eager to start a global conversation on that global history.” To that end, WIGH both brings foreign scholars to Cambridge, and has established a network of research and teaching nuclei on four continents, with collaborations in China, India, the Netherlands, Senegal, and Brazil.

Because global history by its nature is inclusive, and actively seeks multiple points of view, says Maier, it has evolved in the spirit of the working-class histories championed by British historian E.P. Thompson in the 1960s. In that sense, “there is a moral component” to it, he feels. “It can’t be only about empires. It’s not that spatially you miss much,” he explains, “but empires are the stories of elites.” In global history, “voices cannot be hierarchized. You have to give the global South its voice,” for example. “Each history has to be written from its own perspective.”

One of the large questions that global history seeks to answer is why social structures that maintain the power of elite minorities are perpetuated. Maier notes “the fractal nature of social organization, as patterns repeat themselves at different levels of society, and across cultures. How do they carry on so strongly,” he wonders, “when they benefit such a small group of people?”

The “Great Divergence”

Beckert himself has sought to answer this big question through a decade-long study of cotton—the commodity that started the Industrial Revolution and, he argues, shaped the present global capitalist system: glorious at its best, but at its worst, a “race to the bottom” that seeks the cheapest labor and materials. Beckert’s work has culminated in Empire of Cotton: A Global History (Knopf), to be published in December. As he writes in the introduction:

Particularly vexing is the question of why, after many millennia of slow economic growth, a few strands of humanity in the late eighteenth century suddenly got much richer. Scholars now refer to these few decades as the “great divergence”—the beginning of the vast divides that still structure today’s world, the divide between those countries that industrialized and those that did not, between colonizers and colonized, between the global North and the global South.

Taking a global perspective sheds fresh light on capitalism’s reliance on transoceanic connections, such as the simultaneous rise of industrial wage labor in Europe and slave labor in America. “We have hundreds of books on the Industrial Revolution in England,” says Beckert, “and these books focus, as they should, mostly on the expansion of cotton manufacturing, because that’s the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. And then we have hundreds of books on the expansion of slave agriculture in the United States. But these stories are, as I show, very tightly linked to one another because with the growth of cotton manufacturing in Europe, huge needs for cotton emerged there. And since cotton does not grow on the continent of Europe, but it grows very well in places like…the United States, there is a huge expansion of cotton agriculture there, almost all of it based on slave labor. Slavery is central to industrial capitalism as it emerges in the nineteenth-century.”

Beckert tells how in 1785 British customs agents in Liverpool seized bags of cotton from an American ship when it sought to deliver the cargo. They didn’t believe the cotton came from the United States because at that time the plant was grown almost exclusively in the Ottoman Empire, the West Indies, Brazil, or India. “That the United States would ever produce significant amounts of cotton…seemed preposterous,” he writes. It was, he concludes, a “spectacular misjudgment,” given the ensuing transformation of the American South from producing “tobacco, rice, indigo, and some sugar” to producing cotton. And it upends the American sense of independence and self-determination: European industrialists and financiers were key to this transformation of the American South.

Taking a global view allows Beckert to explore why, for example, beginning around 1800, more cotton wasn’t cultivated in India, where it also grows well. At issue was not just the fact that slave-labor exploitation in the American South made production there cheaper. “Even though the British wanted to get cotton from India,” he explains, “they more or less failed in that project until the later part of the nineteenth century because of the difficulty of recasting colonial India’s political, social, and economic structures.”

Then the American Civil War, and the end of slavery, triggered the world’s first raw materials crisis. “It would be as if, suddenly, no oil came from the Middle East,” Beckert says. European textile manufacturers were forced to find new sources of raw cotton. Focusing their attention on Egypt, India, and Brazil, they eventually succeeded in transforming agriculture in those parts of the world to extract more cotton.

Global history is “the kind of idea that, once you have it, is impossible to go back from,” Beckert continues. “You can’t. It’s going to be with you forever because it’s just a different way of seeing history.” While it opens new questions, it “also opens up totally new understandings of particular historical problems such as the problem of slavery. You understand, on a global scale, that the global problem, from the perspective of European colonialists and European entrepreneurs, is really how to transform the countryside. The resulting transformation takes different forms in different parts of the world, but sometimes it’s also quite similar. After the Civil War, for example, sharecropping becomes dominant in the United States, but it’s also important in Egypt, Mexico, Brazil, and other parts of the world. People in these places learn from one another. They observe one another.”

Capitalism can make strange bedfellows. Beckert relates how in 1898, the German ambassador to the United States approached Booker T. Washington, asking him to send students and professors—the sons and grandsons of slaves—from Tuskegee to Germany and then on to the West African colony of Togo to transform cotton agriculture there: “an amazing story of African Americans advising deeply racist German colonialists in Togo about how to make local peasants produce cotton for world markets.”

Beckert’s work played an important role in attracting graduate student Joan Chaker to Harvard from Lebanon. She’d written her master’s thesis years ago about the tobacco market in the Ottoman Empire, but quickly came to understand that she could not comprehend that history without looking beyond Turkey, to European financiers and their interests. After a stint as a banker in Amsterdam, Chaker resolved to return to academia. When she discovered Beckert’s work on cotton, it was “enlightening” she recalls, “because it explained a lot of history in the Ottoman tobacco market.” Like cotton, tobacco is a global commodity, and the American civil war allowed Turkish tobacco to acquire an important share of the global market. “I saw that I could transpose ideas from his framework to mine,” she says.

“I think students are catching on to the excitement,” says Beckert, “and to the fact that we have this institution now where they can connect, meet each other, other faculty members, visitors, and postdoctoral fellows who have taken a great role in helping them with their research papers.” Training the rising generation of historians in this way “makes it possible for them to embark upon projects that would likely have seemed too ambitious for a student even a few years ago. And they have the opportunity to become part of a global scholarly community from their first year in graduate school.”

In a 2009 essay, Maier noted that teaching global history to undergraduates has been one of the most difficult challenges of his career “because of the sheer volume of new information students confront.” Still, he wrote, “introducing global history strikes me as the most imperative challenge for historical teaching today,” given “the readjustment of American power and wealth, the migrations of new citizens, the clamorous challenges of inequality and environmental fragility.” The challenge of ensuring that undergraduates are familiar with basic historical timelines and factual details that undergird more detailed studies will become more acute if a course in global history is developed in the College. But there is enthusiasm for attempting this, says Beckert, even among faculty members not presently involved in the initiative.

Alternative Histories

Global history is not just economic history, Beckert emphasizes. Julia McClure, a WIGH postdoctoral fellow during the 2013-2014 academic year, studies a kind of global network radically different from his capitalist empire of cotton. Her ambitious goal is to understand how knowledge of the world is structured and formed. She is pursuing her subject by studying Franciscan missionaries, who traveled the globe from southern Europe in the Middle Ages and early modern era, quietly establishing a network of knowledge about its farthest reaches.

Franciscans arrived in the Far East years before Marco Polo did in the thirteenth century. They traveled to Scandinavia and North Africa. They played a key role in shaping Spanish colonialism in the Americas. Everywhere a new land was brought into the European orbit, it seems, Franciscans were there first. Yet the primacy of their explorations, though recorded in detail, is virtually unknown. In McClure’s view, this underscores the ways in which “history itself has been produced and used…to further nationalistic goals.” Whether to exert power or stake colonial claims, nations want to show that they discovered certain regions first. The Franciscans, “without that power agenda, have been left out” of the history books. Although they recorded what they found, few non-Franciscans have read their records. McClure recently obtained a copy of a letter, found in a Franciscan monastery in Bavaria, that was written in 1500 from the island of Hispaniola, where colonization initiated by Christopher Columbus and his son Diego ultimately decimated the native population. The letter “reveals much about the first years of the encounter history,” she says, but it is little known because no one has looked in depth at the Franciscan chronicle of what happened there.

Her work “puts the Middle Ages into a global context,” McClure says. “People think global connectivity begins in the nineteenth century with telephone cables, but it exists in the Middle Ages, and one way to represent that is through the movements of the Franciscan order.” The larger importance of that revelation is that “there is an alternative account of global history.” She aspires to use the Franciscan version of global history to pioneer an approach and perspective that lets students and others see traditional, mainstream history as a narrative constructed with intention—whether good or bad: a narrative that might be told in other ways.

Reaching Beyond the Written Record

Global history might be said to embody a simultaneous expansion of perspective and geographical scope. The science of the human past adds a third dimension: time. “Science is dissolving the boundary between history and prehistory,” explains Michael McCormick. “Historians have been confined until now to texts. Suddenly, we can chart the movements of groups of early humans in Africa” and beyond, he marvels, “and we see the human past as a much longer and deeper story.”

“It is so exciting to be an historian today,” McCormick continues. “History is exploding and transforming as the material past becomes an integral part of the historical record. We can no longer be satisfied with texts, because we are just as likely to learn something from a pot or from the lipids preserved in the fabric of the pot that tell us whether they were cooking cabbage or chicken for dinner in the seventh century A.D. when the Anglo-Saxons were taking over England (see “Who Killed the Men of England,” July-August 2009, page 31). Using DNA, “we can map human migrations or identify the genetic groups present, for example, in a burial ground from the Black Death [bubonic plague] in London, or from an imperial Roman estate in southern Italy,” McCormick says. “These are just the beginnings of the application of genetics and isotope studies to migration and questions of diet.”

A further implication of this approach, he points out, is that historical inquiry is “no longer limited to the most powerful people, who were usually the only people to make it into writing. We can see the history of individuals who had no surviving voice in the record coming back almost to life.”

During the 2013-14 academic year, McCormick co-taught History 1940, “The Science of the Human Past” (cross-listed as Human Evolutionary Biology 1940) with Clay professor of scientific archaeology Noreen Tuross. One student in the class, Marie Keil ’14, who had originally planned to become a chemist in the materials industry, changed her mind after hearing a guest lecture by Fenella France (who has used multispectral imaging to decipher erased texts in Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence). Keil spent the ensuing summer working with France at the Library of Congress in chemical analysis of ancient inks, and is now pursuing a master’s in archaeological chemistry at Oxford. Another student, Brendan Maione-Downing ’13, worked for a year after graduating as managing editor of the Digital Atlas for Roman and Medieval Civilization, a free online atlas of the ancient world created by McCormick and his students that maps everything from Roman cities to ancient shipwrecks in the Mediterranean. Maione-Downing has gone on to a career in GIS (geographic information systems). McCormick marvels, “Brendan and Marie discovered their life’s work through one new course in the science of the human past.”

McCormick’s own life work is the fall of the Roman empire and origins of Europe. A longstanding question, now poised to be answered through techniques that Tuross has pioneered, concerns the origins and production of silk within the empire. As cotton would link the industrializing world a thousand years later, silk linked the ancient, precapitalist world. The so-called Silk Road, 4,000 miles long, consisted of a number of trade routes that connected China to the Mediterranean, and was essential to the economic development of these and intervening empires in India and Persia. “Luxury industries,” says McCormick (citing Werner Sombart, an early-twentieth-century historian of capitalism), “are the places in which capital first came together to do amazing things and multiply wealth. It was an early generator.” Because the fabric was one of the first global commodities, “volumes and volumes have been written on where a particular piece of silk comes from,” McCormick explains. “It’s really important for art history, for culture, for the economy.”

Because silk is light and easily transported, it “was worth many times its weight in gold,” McCormick continues. “If you’re carrying something from China to Italy on camelback and making money on it, it’s extremely valuable.” Pliny the Elder writes about the vast sums that Rome is sending to China and India in exchange for spices and silks, “but we don’t know where the silk that is being used in the Roman empire is coming from.” Very little is known about the spread of silk-making technology in the ancient world, or the history of the trade, because the many bits of silk fabric retrieved in archaeological digs or held in museums are hard to date and localize: on a trip to the textiles section at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, McCormick says, the class met with curators and “looked at the weave through a microscope and talked about established methods people have used” to identify the fragments’ origins.

Silk production is especially fascinating because silkworms cannot live without human care. Released into the wild, they die. In the sixth century a.d., the emperor Justinian reportedly sent industrial spies to the “Silk Land” (according to the Greek text) in order to bring the secret of silk production back to his empire. “They hollowed out their walking sticks and filled them with silkworm eggs,” McCormick relates. “And then they started silk production inside the Roman empire—according to two detailed written records in the original Greek sources.”

But some historians claim the empire was producing silk much earlier. This important historical question will likely be settled soon because Tuross, a chemist, has developed a technique for pinpointing the origins of ancient shreds of silk fabric. She is an expert in isotope analysis. By examining physical remains, for example, she can discover what food individuals ate during their lifetimes, the places where they grew up, and whether their lives ended somewhere else. At a symposium on the science of the human past in the fall of 2013, she described how the Arctic voyages of seventeenth-century Dutch whalers become etched in isotopic signatures in their teeth. Changes in people’s diet—even in the water they drink—can reveal where they have lived or traveled. Tuross earlier used such analysis to characterize the diet of Neanderthals (see “Who Killed the Men of England,” page 35), shattering myths about their putatively carnivorous tastes. “Now, using Noreen’s methods,” says McCormick, “we’ll be able to show whether silk was being cultivated inside the Roman empire before the sixth century. We’ll be able to see its introduction to Spain, to Sicily, to Italy, and ultimately to France. And we’ll be able to track the spread of the technology, after the Islamic conquest, throughout the Islamic world.” Scholars may find evidence of competition between China and India, or something wholly unexpected: McCormick tells how French researchers using the Louvre’s particle accelerator to analyze the origins of garnet jewelry from the Roman empire discovered interruptions in the trade of these red gemstones from India and Sri Lanka. Demand had remained high (the Romans eventually sought and found new sources of supply), raising the question, “What happened in India, Sri Lanka, or along the way that interrupted this trade?”

The question is important because these economic exchanges, which show that even the ancient world was an interconnected place, underlie pivotal cultural exchanges: of art, design, and ideas that shaped the subsequent course of history.

The Global and the Local

The Initiative for the Science of the Human Past might be said to have launched important cultural exchanges of its own, by putting historians in contact with scientists. In 2012, McCormick and Peter Huybers, professor of earth and planetary sciences and of environmental science and engineering, with other colleagues, published the first general survey of climate change within the Roman Empire, from 100 b.c. to a.d. 800. They showed that climate crises were closely linked to the expansion and contraction of the agriculturally dependent empire. They are now working on a broader project that combines climate proxies such as tree rings, speleothems (mineral deposits found in caves), and ice-core analyses with the written record for five major climate crises spanning the years a.d. 536 to 1741 not only for Europe, but also for China and Japan. The collaboration is mutual, because the scientists will use existing written records—what Huybers has termed “the most powerful proxy record there is: a human being who was there who will tell us what happened”—to help calibrate their scientific methods.

The collaboration extends into computing and genetics as well. Welch professor of computer science Stuart Shieber, for example, has developed programs for analyzing texts. In one demonstration, he was able to identify in a few minutes all the biblical references in a written record—work that had taken a class of students a week to analyze. He is now working with McCormick to develop a method for dating published Latin biographies of Christian saints. “There are 14,000 of them,” explains McCormick. “Of these, 6,000 have been dated to within a period of 500 years or less. That means there are 8,000 texts that no one has even bothered to look at. If we could date just 10 percent of those, that would be 800 new texts for historians to work with”—in an area “we thought to be well-mapped.”

Meanwhile, at Harvard Medical School and the Broad Institute, professor of genetics David Reich and visiting scientist and research fellow Nicholas Patterson use genetics to trace early human migrations and conquests. With the initiative’s first postgraduate fellow, Sriram Sankararaman, they are working to understand the genetic variations contributed to modern humans by archaic hominins such as Neanderthals and Denisovans (see “Human Family Reunions,” July-August, page 7). Separately, they have explored the genetic origins of the peoples of the Indian subcontinent, showing a recent population admixture, and have elucidated the origins of Native Americans. McCormick is realistic about his own interest in whether genetics will be able to determine who, precisely, the barbarians were who sacked Rome. But in part because the genetic differences between the conquerors and the conquered may be too small to see, as he acknowledges, McCormick says Reich and Patterson are right to concentrate on the “gigantic” questions: “the out-of-Africa event, the peopling of Australasia, the origins of Indo-European languages and whether they are tied to population movements.”

McCormick never suspected that his own sphere of interest—the Roman empire—would extend beyond its ancient boundaries. But science has been for him a path to discovering a broader perspective that links to the work of other colleagues in the history department, a turn to the global and the quantitative in the study of history. “When I started out in graduate school,” he says happily, “I had no idea that what was going on in China could be of any interest to me. Wrong again!”

“Entangled history,” or the ways that societies affect each other, is one thing. Entangled historians are quite another. During the six months he spent on campus finishing his book on May 1968, Omar Gueye learned much from the global history program, other global-history fellows, and the books he found in Harvard’s library (“for some, I am almost sure I am the first person to see them”), as well as from other professors at the University: professor of history Lisa McGirr, for example, who lectures on “protest and politics” in American history, including the 1960s in the United States; and Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal professor of contemporary Islamic religion and society Ousmane Oumar Kane, who has studied religion among Senegalese immigrants in New York City.

These intellectual exchanges often prompt unexpected discoveries. One student from Taiwan was astonished to learn from Gueye that there were Taiwanese students studying in Dakar in 1968. And Gueye hopes there will be many more such productive exchanges to come, now that a global network of scholars has been formed. A conference on global conceptions of freedom—of particular interest to historians of slavery in Senegal and Brazil—may take place in Dakar in 2015. How did ideas of freedom emerge around the world? What do they have in common? How do they differ, and how do they inform each other? “The goal of this program is to open up dialogue and perspective,” Gueye says. In the past, “People talked about world history. But now we have a strong network of people who formally think about it together.”