“Guess who was the most photographed American of the nineteenth century.” Fletcher University Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr., director of the Hutchins Center for African and African-American Studies, prepares for the surprise on my face.

As it turns out, the answer is Frederick Douglass. Researchers have found at least 160 photographs of Douglass, who praised the medium of photography for enabling him to counter the racial caricatures so frequent in artistic representation of black people at the time. It should not be wholly surprising that one of the most prominent American figures of his era would also be the most photographed—yet black history is often marginalized in the history of the West.

In the Hutchins Center's Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art, Gates and I stand in front of a portrait of a black man, Peter Jackson, taken in 1889. Jackson, wearing a top hat and a three-piece suit, occupies the full frame with what Gates describes as “Victorian African swag.” Jackson’s hands rest casually in his pockets as he gazes assuredly at the camera, refusing to be erased.

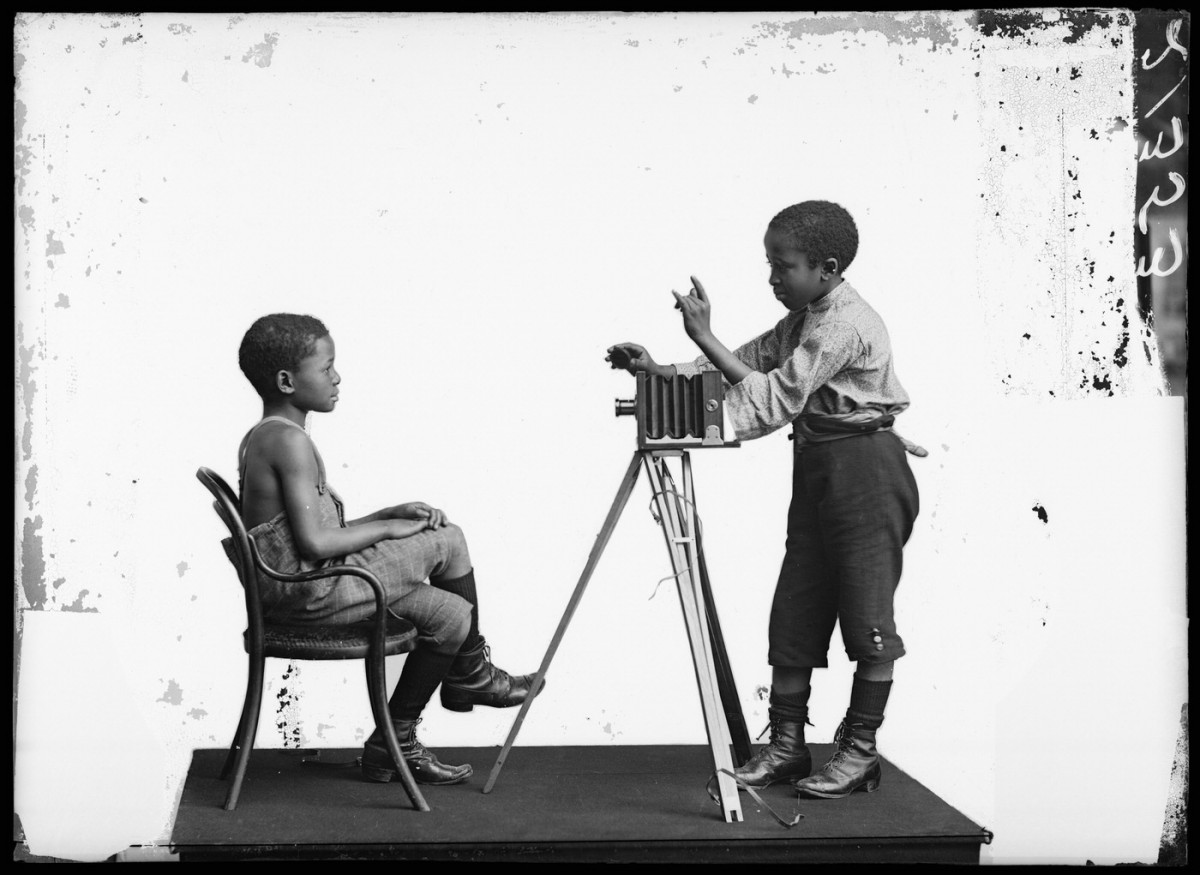

Opening to the public on September 3 and on display until December 11, Black Chronicles II presents photographs of people of color (most are black, some are South Asian) in nineteenth-century Britain. In a world that rarely portrays black people in positions of regal power and dominance, the exhibit asserts the existence of people of color in the photographic record, and more broadly, the Western historical narrative. The exhibit’s stay at Harvard—a university campus where dining halls and libraries are adorned almost exclusively with pictures of white faces—marks the first appearance of these images in the United States.

The exhibition, curated by Renée Mussai and Mark Sealy of Autograph ABP, a British nonprofit that advocates the representation of historically marginalized communities in photography, is a collaboration with the Hulton Archive/Getty Images of London; the majority of its photographs were printed large-scale from their glass-plate negatives for display for the first time since the 1880s. Black Chronicles II represents an ongoing research project for Autograph ABP. “During the early stages of the research, we made the somewhat maverick decision to showcase the work as it emerges,” says Mussai, who noted that she and Sealy released images within months of their discovery at the Hulton Archive.

Representation is at the core of the exhibition’s mission. “When we as black people search for representations of ourselves, too often we encounter a series of gaps, of absences and omissions,” says Mussai. And the gap in the British record of the nineteenth century was especially large: “In the U.K., at least, it was largely unexplored and open territory in terms of the history of photography.” Currently at work on her doctoral thesis—on photography, race, and the black body in the archives—Mussai adds, “When I first started working on this project, I would have struggled to cite more than five images. Now we have hundreds to reference.”

A visual commentary on common memory and power, Black Chronicles II is dedicated to the memory of British cultural theorist and sociologist Stuart Hall. In the Cooper Gallery, excerpts from his 2008 lecture at Rivington Place, a global art center in London, adorn the walls. In that talk, “The Missing Chapter: Cultural Identity and the Photographic Archive,” Jamaican-born Hall spoke about the importance of memory and the importance of resisting what he called “systematic forgetting.” One quote—above the entrance to the main portion of the exhibition—stands out: “They are here because you were there”—a reference to the British empire-building in the latter half of the nineteenth century that brought so many of the portrait sitters into their British context. Sarah Forbes Bonetta and Prince Alemayou, Mussai explains, were brought to Britain from modern-day Nigeria and Ethiopia by British agents of Queen Victoria and educated as part of the British middle class. Kalulu, who was companion to the infamous British explorer and journalist Henry Morton Stanley, also appears. The quote “poignantly evokes the intimate connection between Britain’s colonial history and many of the sitters in these portraits,” Mussai says,“and reminds us that it is impossible to look at the notion of Englishness without critically engaging with its imperial and colonial history.”

It’s similarly impossible to look at the images without considering the frame of the white gaze. The exhibit includes more than 30 portraits of the African Choir, a South African ensemble who traveled Britain from 1891 to 1893. In many of these photos, the members dress in more traditional South African clothing, not in the Victorian attire they would have ordinarily worn in their day-to-day lives in middle-class South Africa. Mussai puts it this way: “There are complexities. Knowingly, or as part of whatever business arrangements they had to make, they engaged in the spectacle of staging their identity in a space of difference, reflective of a certain image of Africa, steeped in fantasy and myth, that was prevalent in the Victorian public and imagination at the time.”

Eleanor Xiniwe, The African Choir. London Stereoscopic Company, 1891.

Courtesy of © Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In his 1861 address at Boston’s Tremont Temple, Frederick Douglass said, “Pictures, like songs, should be left to make [their] own way in the world. All they can reasonably ask of us is that we place them on the wall, in the best light, and for the rest allow them to speak for themselves.” The exhibit (which has minimal text accompanying the photos) seems to heed Douglass’s advice. Mussai wrote me, “The notion of the sitters’ gaze and a sense of agency, dignity, and beauty emanating from the portraits is crucial in the curatorial organization of the exhibition: especially as you sit in the final gallery, surrounded by the different members of the African Choir, each engaging the viewer directly.” To Mussai, the final gallery is a “space of transformative encounters, and a kind of sanctuary to appreciate, reflect, and imagine what their lives might have been like…and what our lives are like today.”

Black Chronicles II may also spark a more intimate and sacred encounter between black viewers and its images. Mussai is inspired by the relationships that individual museumgoers create with the portraits. She tells me about a black mother who brought her five children to the exhibition multiple times when it was first on display, at Rivington Place in 2014. Mussai was struck, she says, by how the mother was “allowing her children to basically almost ‘verify’ their existence by looking at these nineteenth-century images, revealing to them the very important fact that black people have been in this country for centuries, have a long history here, and are represented with a certain grace and dignity.”

Albert Jonas and John Xiniwe, The African Choir. London Stereoscopic Company, 1891.

Courtesy of © Hulton Archive/Getty Images

For black people, existence and resistance are not separate. The ability of these nineteenth- and twentieth-century images to engage with black activism in our current political moment is not lost on gallery director Vera Ingrid Grant, who, when asked about how the exhibition fits into ongoing conversations about race in America, said of Harvard, “This is not a political place, but an academic one—this is a nonprofit university.” But, at the Cooper Gallery, she added, “We may negotiate that line, and we will move forward with full intent to do what we may do. Art has a different and open discursive agenda in which things may be discussed that perhaps may not be addressed in a formal, textual space of discourse.” Grant aims for the gallery to be open to community outreach and student initiatives that bring it into more direct conversations about current events.

Mussai describes photography as a “wonderful, perfect political tool, because it leaves no place for doubt when it comes to documenting people's existence. It provides visual evidence. These people were definitely here.”

And we are still here, speaking.