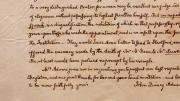

A feisty letter written in 1819 in the distinctive hand of John Quincy Adams, A.B. 1787, A.M. ’90, LL.D. 1822, hangs today, framed, in the office of Harvard president Drew Faust. It offers outspoken candor about yesterday’s faculty politics to anyone who happens to read it while standing around waiting for today’s action to unfold. A snippet appears below; the entire letter may be read on this magazine’s website.

Adams, who was then the nation’s secretary of state, wrote tartly about a range of Harvard topics to his close friend, Ward Nicholas Boylston, a cousin of his father, John Adams, A.B. 1755, A.M. ’58, LL.D. ’81. “I speak the whole truth to you,” he wrote, “because nothing less can do any good.”

Boylston was the nephew of the founder of the Boylston professorship of rhetoric and oratory, and John Quincy Adams had been the first to hold the post, serving for two years part-time starting in 1806, commuting from his Senate service in Washington, D.C., to Cambridge. After him came a minister, the Reverend Mr. Joseph McKean, as Jay Heinrich tells in his history of the professorship (“How Harvard Destroyed Rhetoric,” July-August 1995, page 37). The concerns of the job, writes Heinrich, “gradually drifted away from oral address, political meaning, and anything remotely practical.” In his letter to his friend Boylston, Adams bemoaned McKean’s appointment.

“With regard to the professorship of rhetoric and oratory, I do most sincerely wish it could be given to a person capable of understanding its duties, and of performing them,” he wrote. “To Mr. M’Kean [sic] it was a sinecure, given him for his wants and his vices, and not for any quality required by the place....But the corporation of Harvard University, though including some of the best men in the world, is and for many years has been more of a Caucus Club, than of a Literary and Scientific Society—Bigoted to religious liberality and illiberal in political principle—When they have a place to fill, their question is not, who is fit for the place, but who is to be provided for? and their whole range of candidates is a Parson, or a Partizan, or both.”

Adams goes on to disparage clerics wholesale as candidates for the professorship. “The Pulpit is indeed one of the scenes of practical oratory,” he writes, “but it is oratory of the lowest class. The Pulpit Orator has no antagonist. There may be triumph without a victory; but there can be no victory without a Battle. Now as in the days of Cicero, the great struggle and the most spendid theatre of eloquence is at the Bar.”

For good politically incorrect measure, Adams opined, “an impediment of speech is a disqualification, the exhibition of which in that professorship reflects disgrace upon those who made the appointment, and is an insult upon the founder of the Institution.”

The letter is a gift to Harvard from David M. Rubenstein, a Harvard parent, graduate of Duke and the University of Chicago Law School, and co-founder and co-chief executive officer of the investment firm The Carlyle Group—a more than usually philanthropic billionaire who co-chairs the Harvard Campaign and the Kennedy School campaign.

On cats: The late Daniel Merton Wegner was the Lindsley professor of psychology in memory of William James, but “first and foremost, he was an inventor,” write three of his colleagues in a memorial minute about him presented to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences last December. He started out in college studying physics and engineering, but switched to social psychology. “Although he ultimately became a widely celebrated éminence grise who won every major award his field could offer, he never stopped being the ten-year-old boy who sat in the attic of his house in East Lansing with an issue of Popular Mechanics and a chemistry set, trying to develop a formula that would turn the family cat into a family dog because, as he would maintain for the rest of his life, there is simply no good reason for cats.” One hopes, piously, that no harm befell the cat in this attempted alchemy.