Jason Bouldin ’89 always notices the hands: how they move when a person speaks, where they come to rest, whether they’re folded or open, fidgety or quiet, how they cradle the chin or fall into the lap or reach out across a table. For a portrait painter like him, every gesture offers a small universe of information, the same as gait and posture and facial expression. “Because, you see,” he says, “what I’m always trying to get at is not only what somebody looks like, but what they feel like.”

In Bouldin’s mind, a portrait is like a poem—so much to say, so little space to say it. “I can’t give you a two-volume biography on somebody,” he adds, speaking from his sunlit studio in Oxford, Mississippi, wearing the paint-speckled red apron he puts on most days, “but I can suggest enough so that when people see the portrait, they say, ‘Oh, he got that man’s spit!’ Which means, made the intangible image tangible.”

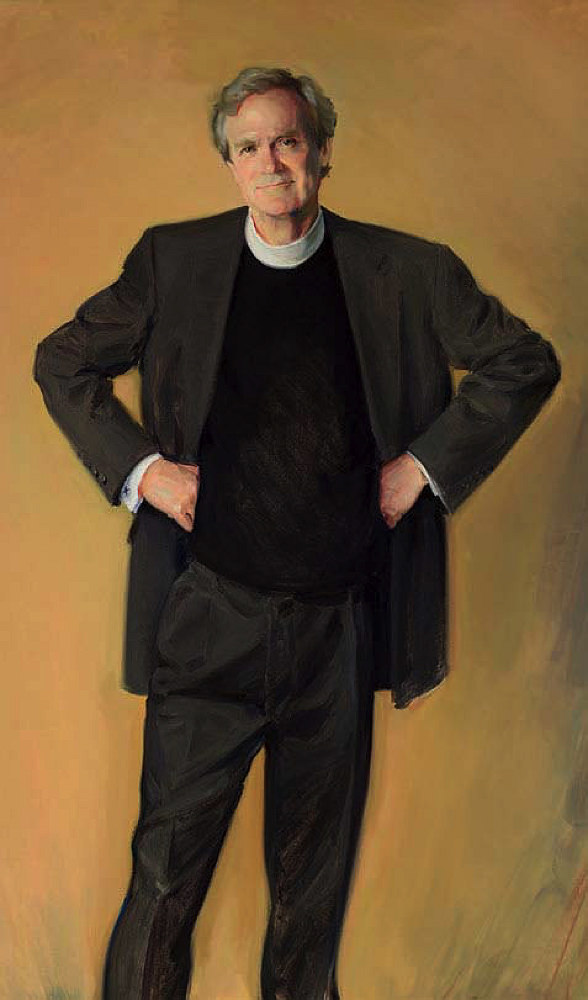

Jason Bouldin's portrait of the Reverend Sam Lloyd

Painting courtesy of Jason Bouldin

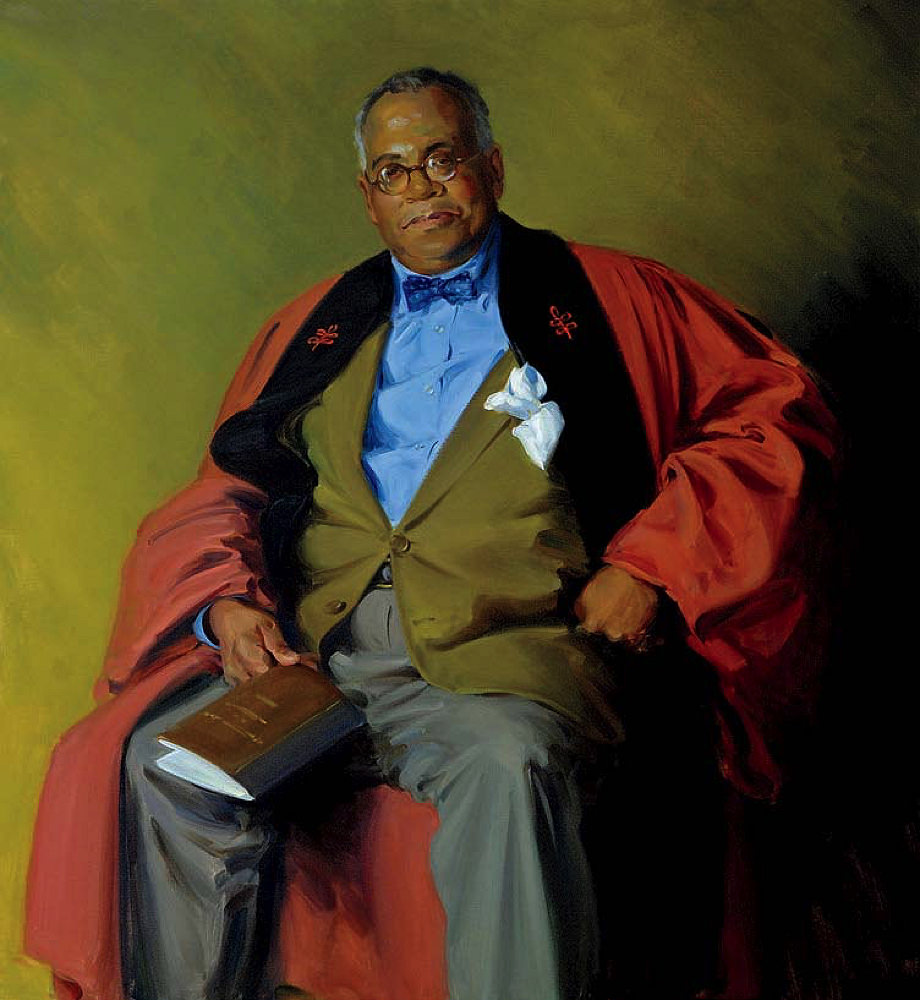

Here’s what Episcopal priest Sam Lloyd “feels like” in Bouldin’s rendering: buoyant and warm, comfortable and comforting, a man who, as one parishioner told the painter, is more pastor than preacher. A former dean of the Washington National Cathedral and rector at Boston’s Trinity Church, Lloyd stands with his hands at his waist and his legs in lanky motion, an unguarded posture that matches the easy smile radiating from the canvas. Similarly, Peter Gomes, the late Plummer professor of Christian morals and Pusey minister in Harvard’s Memorial Church, sits, in a Bouldin portrait from 2002, with his knees relaxed open and one hand on his hip, a scarlet academic robe billowing from his shoulders. In the lines of fabric stretching from the jacket button fastened at his generous belly, you can almost hear Gomes’s booming voice. Bouldin, who was head usher at Memorial Church his senior year (“Jason, my boy!” he remembers the minister roaring down the aisles), painted the portrait for Roxbury Latin School, where Gomes was a board member.

Bouldin's 2002 portrait of the late Reverend Peter Gomes

Painting courtesy of Jason Bouldin

The feeling in Bouldin’s portrait of federal judge Diana Murphy, painted a few years before her death in 2018, is a mix of strength, fatigue, and ironic humor. Half-smiling, her black robe zipped to the collar, she sinks deep in her chair, head leaning on a hand disfigured by rheumatoid arthritis, a disease she lived with for decades. (At first, she did not want her hands included, but Bouldin persuaded her, believing they were meaningful and important.) Behind her, filling the top half of the portrait, hangs a massive abstract painting that decorated Murphy’s chambers; titled Trinity, it was created by a Minnesotan monk, and its presence here, Bouldin says, communicates—along with her hands, robe, and weary eyes—the moral weight of Murphy’s work: “The idea of both a body and a spirit, the written code and the spirt of the law, and the judge as the intermediary between them.”

It takes Bouldin six months to a year to execute each portrait, a process that begins with several in-person meetings, where he asks questions, snaps photos, and gathers ideas. Back in his studio, he produces several small color sketches and a life-size charcoal drawing—“my blueprints,” he calls them. Once everyone agrees to the design, he starts putting paint on the canvas.

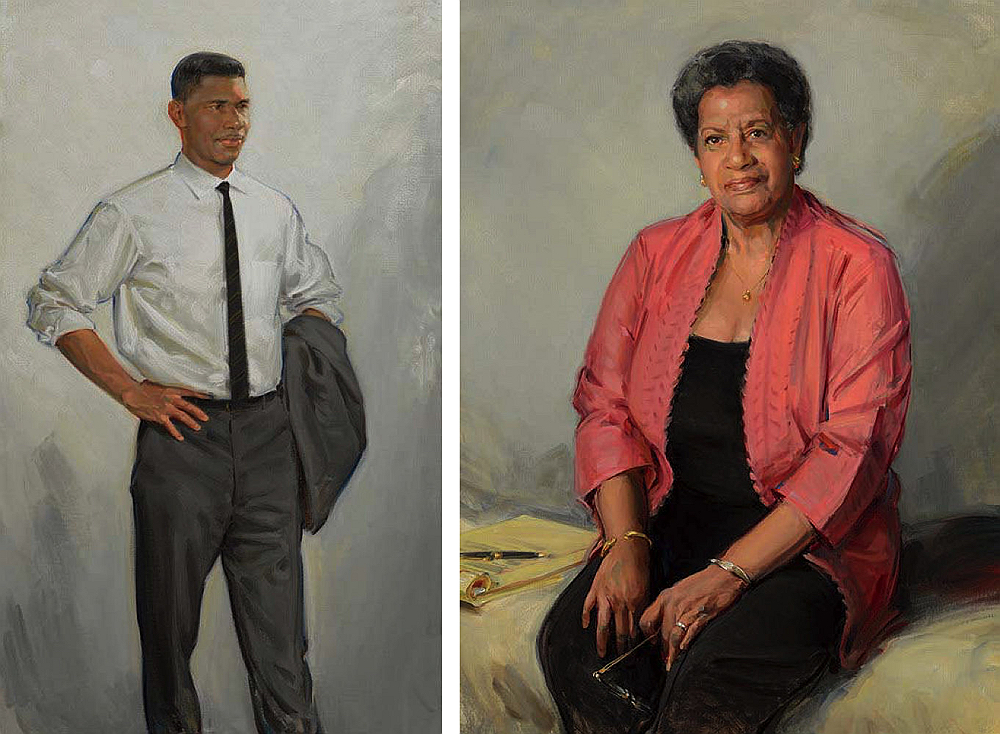

Medgar Evers and his widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams, painted on the 50th anniversary of Evers'1963 murder

Painting courtesy of Jason Bouldin

Bouldin has painted hundreds of portraits this way: governors, senators, judges, clergymen, corporate leaders, university presidents (including Harvard’s Derek Bok), scholars, firefighters, museum employees, and private collectors. “A lot of people think portrait painting is all about prestige,” he says, “but for me it’s more about memory. It’s a visual image reminding you of who you are and to whom you belong.” His work hangs in federal buildings (including the House of Representatives), courthouses, museums, offices, and college campuses; Bok’s portrait is in the Harvard Art Museums. In 2013, the Mississippi Museum of Art commissioned him to paint Medgar Evers and his widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the civil rights leader’s assassination in Jackson. Side by side, the portraits tell a story, “of a life cut short and a life that carried on.”

Bouldin grew up on his family’s cotton farm in Clarksdale, playing alongside his three older brothers in the henhouse that his father, portrait painter Marshall Bouldin III, had converted into a studio. The elder Bouldin painted subjects including Richard Nixon’s daughters, astronaut Ronald McNair, writer William Faulkner, and all manner of Southern political leaders. Meanwhile, his mother, Mary Ellen Stribling Bouldin, a gynecologist and obstetrician, maintained a practice 75 miles away in Memphis and flew herself back and forth in a small airplane. (In 1968 she helped deliver Lisa Marie Presley, Bouldin says: “Mama got to tell Elvis it was a girl.”) “We were an oddball family,” he recalls.

At Harvard, Bouldin studied art history—“which gave me the lexicon and the theoretical framework”—but his only true teacher was his father. During college summers and for two years after graduation, he was his father’s apprentice, learning how to shape a brush, follow the rules of perspective, mix paints with precision. “One summer I mixed around 2,500 different colors,” he says. “I’d make charts and mix a little more and make more charts.” In 1991, he set off on his own.

his still life Lazarus Bird

Painting courtesy of Jason Bouldin

Grass, Graball Landing,Tallahatchie County

Painting courtesy of Jason Bouldin

Like his father, Bouldin’s first love was illustration, and apart from his commissioned portraits, he paints landscapes and still lifes. Several are on display through February 14 at the Walter Anderson Museum of Art, on Mississippi’s Gulf coast, as part of Bearing Witness: Southern Visual Elegies, an exhibition on death, remembrance, and rebirth. One painting depicts a Carolina wren that Bouldin accidentally killed while trying to free it from a Sunday school classroom (on a day when the lesson concerned Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead); another gathers grasses and grapevines from Graball Landing on the Tallahatchie River, the site where Emmett Till’s body was found, which Bouldin visited on a clear blue February day. The painting’s arrangement evokes the open casket and the boy’s mutilated body, the bread and wine of communion, and a funeral shroud—or perhaps, he says, a flag, “like the rebel flag people batter about for so-called ‘heritage.’”

Broken Pecan in front of Daddy's Studio

Painting courtesy of Jason Bouldin

Some of the most moving works memorialize Bouldin’s father, who died in 2012. Broken Pecan in front of Daddy’s Studio shows the aftermath of a tornado that struck after his father’s death, snapping a 100-year-old tree in half. “The power of the storm, and the freshness of the bark inside this very old tree—it just seemed so tragic,” Bouldin says. “Painting it became a sort of grieving Daddy’s loss, this powerful tree in my life that’s broken.” But it’s also a reminder, he says, “that we couldn’t enjoy this world if we were not carnal creatures that ultimately die. The real blessing is that we are human.”

Which brings him back to people’s hands. “One of the most meaningful things I did in the last year of my father’s life was to draw his hands,” Bouldin says. By then, his father, 89, was no longer able to sit for a portrait. Instead, Bouldin would draw as he slept. “I have a whole series of charcoal studies of his hands. They were wonderful things”—gnarled with age and half-frozen by paralysis. “But they were specific to him.” He pauses. “As everybody’s hands are.”